Where was I when Kathy Acker was appropriating text and imagery from Rimbaud and performing at the Kitchen and tattooing her body and raging against sexual conformity? Working at MoMA and Lincoln Center and getting married and having babies. I felt utterly conventional and bougie at this exhibition at the ICA London and yet at the time the artists and filmmakers surrounding me seemed avant-garde. Acker’s art needs to be read carefully as well as seen, and so I have catching up to do.

Michelangelo stays at the Met

For the few years I worked at the Services Culturels housed in the former Payne Whitney mansion across from the Metropolitan Museum on Fifth, we used this rather nondescript statue as a coat or hat rack, ashtray, or place to wad a used cocktail napkin. When it was discovered to be a vrai Michelange I was rather nonplussed. My office which was vaguely like a bordello with a white shag rug and dark walls in a remade attic space was only one of many odd nooks in the building which Miss Helen Whitney had done up when upper Fifth was the boonies. Still the statue conferred a sense of decorum and history during a time of my life dearly lacking in same.

Ratmansky Trio at ABT shows off his Russian roots

In between their sumptuous productions of Whipped Cream and Swan Lake, ABT programmed a trio of of Alexei Ratmansky works that felt oddly like a night at their next door neighbors at NYCB.

Ratmansky is probably the most complete choreographer working today. What do I mean by that? As heir to the full panapoly of Russian traditions, and as keeper and burnisher of that flame, many of his ballets—even the more contemporary ones-- still have a Russian feeling and elements that remind of Nijinsky’s Faun or Russian folk traditions. Yet he has learned from Robbins and Balanchine as much as anyone.

Songs of Bukovina from 2017 appears at first to draw on Jerome Robbins’ Dances at a Gathering more than anything else. But then you notice the flat-footed chorus with its flexed feet or the folkloric jumps and poses and the hybrid nature of his work comes to the fore. Isabella Boylston, a Sun Valley, Idaho native manages to imbue the piece with a Russian-inflected insouciance that is lovely and carefree.

On the Dnieper falls more directly in the tradition of ABT story ballet, it received its world premiere in 1932 at the Paris Opera ballet and is 100% in the Russia camp. A story of a tragic Ukrainian love triangle, the period costumes and full-on acting by the cast has an almost kitsch quality that as someone who was emphatically reared on Balanchine finds studied. Still Christine Shevchenko—who is Ukranian-- is such a divine dancer that all else falls away when she takes the stage especially after she becomes the tortured bride.

The Seasons, Ratmansky’s newest work for the company which premiered this week is another of his deep dives into Petipa and as such feels entirely period with added hallmarks of early Balanchine who also drew from this well. It is a joyously danced work which Ratmansky created as a thank you to ABT. (see above video) With moments of choreographic fun and frolic, its four part structure lends itself to lots of chorus, holding poses, and gaiety. I saw the second cast led by Summer’s Stella Abrera (Isabella Boylston danced the first night) Herman Cornejo was alas injured and so Blaine Hoven who had danced in Bukovina was pressed into service and Calvin Royal took Hoven’s spot in the Autumn section.

The house was not full and I imagine that ABT stalwarts find an evening like this one which does not deliver the full on Sleeping Beauty experience a little more challenging. I remember Ratmansky telling me a couple of years ago at the Rolex Arts and Culture weekend, that he’d had no real mentors in Russia, that, “everything my teacher taught me was nonsense.” Yet, as these three ballets show, he is heir to some of their tradition nonetheless.

Scene from The Seasons. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor.

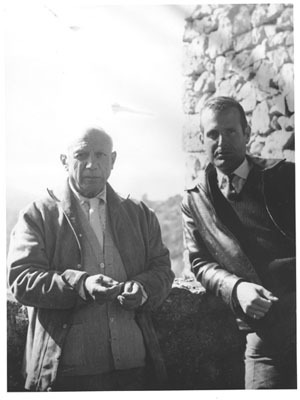

An homage to Picasso's Women and biographer John Richardson at Gagosian

Pablo Picasso, Buste de femme (Dora Maar), 1940, Oil on canvas, 29 1/8 x 23 5/8 in, 74 x 60 cm, © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York, Photo: Erich Koyama, Courtesy Gagosian

When I corresponded with Dora Maar to try to pin her down for an interview for our WNET Picasso documentary at the time of last major Picasso retrospective at MoMA, she was slippery but made sure to ask after John Richardson's whereabouts as she wanted to reconnect with him. She was a tough get, but he got her.

A newly opened homage to Richardson, Picasso's biographer, is also a testament to Gagosian's ability to pull together so many important images in record time. Some of the images of Marie Therese appeared in the Tate Modern retrospective last year. But others felt new to me. Perhaps it’s because I see these images in a slightly different way each time. Recently I too have been examining the role of the women in Picasso’s life and work.

To that end, I often revisit Richardson/Picasso and I'm always impressed by the wealth of personal detail and the profound sense of humor that he brought to this artist, the most chameleon-like of subjects. Richardson organized a number of electric Picasso shows at Gagosian and though this is a less ‘curated’ affair, it still invokes the complex relationships he had with so many of his lovers/muses/wife.

The last upcoming volume of his Picasso biography which will be published posthumously will surely add more delicious tidbits as well as enormous scholarship and I eagerly await it.

An unusual and poignant image of Frida in pain comes to auction

Frida Kahlo underwent something like 40 surgeries to correct the cascade of physical ailments (possible spina bifida, polio, a horrendous bus collision which had driven an iron handrail into her pelvis) which tormented her but which gave her paintings, often made from her convalescent beds, a very particular vantage point and haunting quality. (Kahlo also worked with mirrors to serve as the limbs she was not able to mobilize). This photograph, which I’d not seen before, was sold at Sotheby's—as part of a Nickolas Muray collection— for 28,000 dollars.

Muray is the Hungarian born US based photographer with whom she had a decade long affair. He was married four times, Kahlo almost as many (counting the re-marriage to Diego Rivera, whom she considered her true soul mate.) but they stayed close. Frida in Traction, was taken in 1940 when Muray visited her in the hospital in Mexico, and goes tight on Kahlo’s face which allows the uncertainty of her gaze—will this surgery be the answer?—full measure. Is she accepting or fearful? The folded white cloth around her famous unibrow signifies a moment when Kahlo was incapable of facing down her legacy of pain through her art. But works made that same year which include necklaces which cut into her neck and make her bleed and hearts which are ex-corpus, show she was the eternal phoenix. Muray once wrote to her that he wished he could find “the secret how to make you well again so you could sing, and smile, love and play again as I have seen you before in the bright sun or in the dark night.” As a document of one of those times when she was not able to vanquish her pain, it is unforgettable.

Photo by Nickolas Muray; © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

The San Francisco Maritime Museum: a hidden WPA gem is revitalized

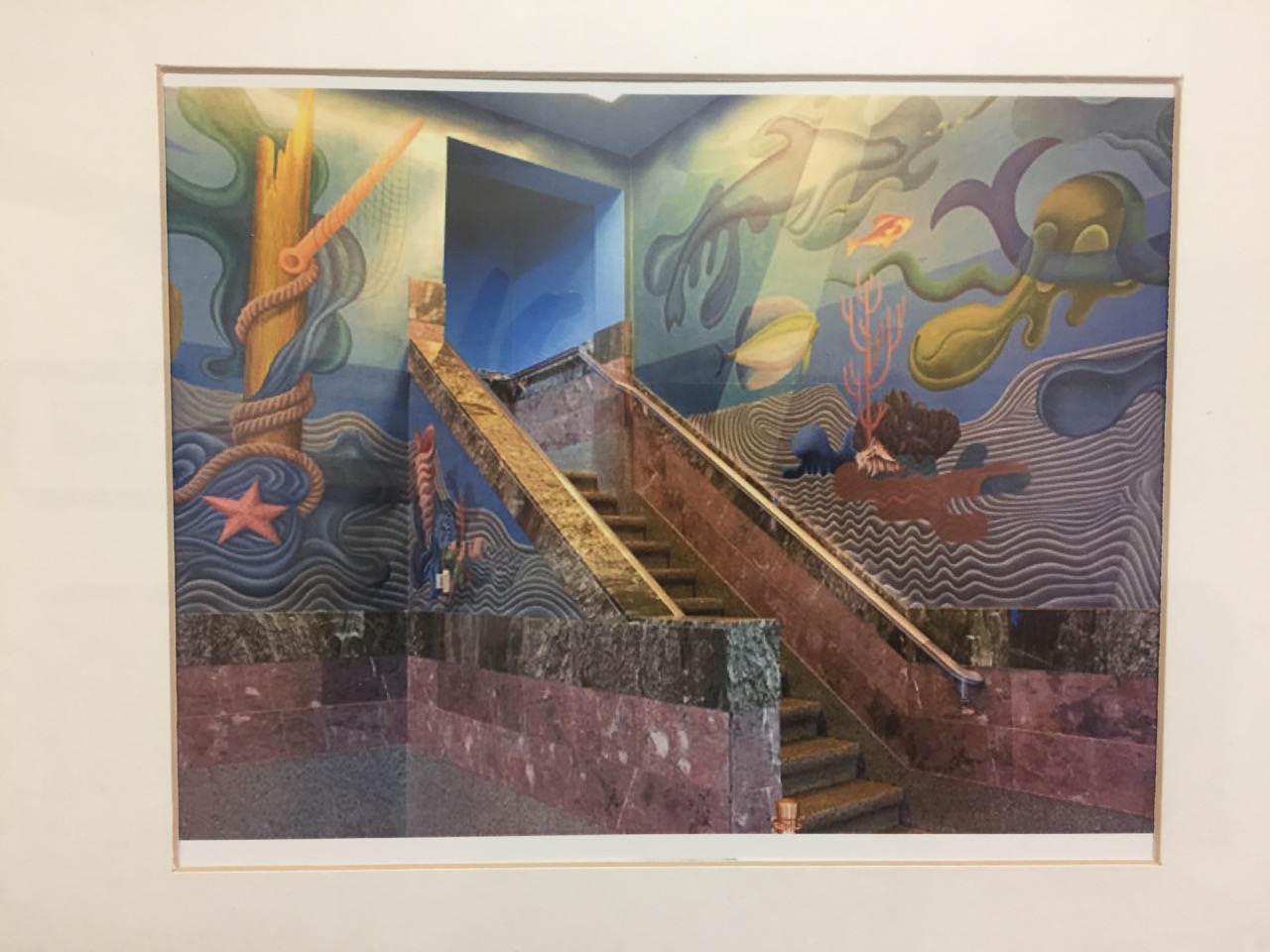

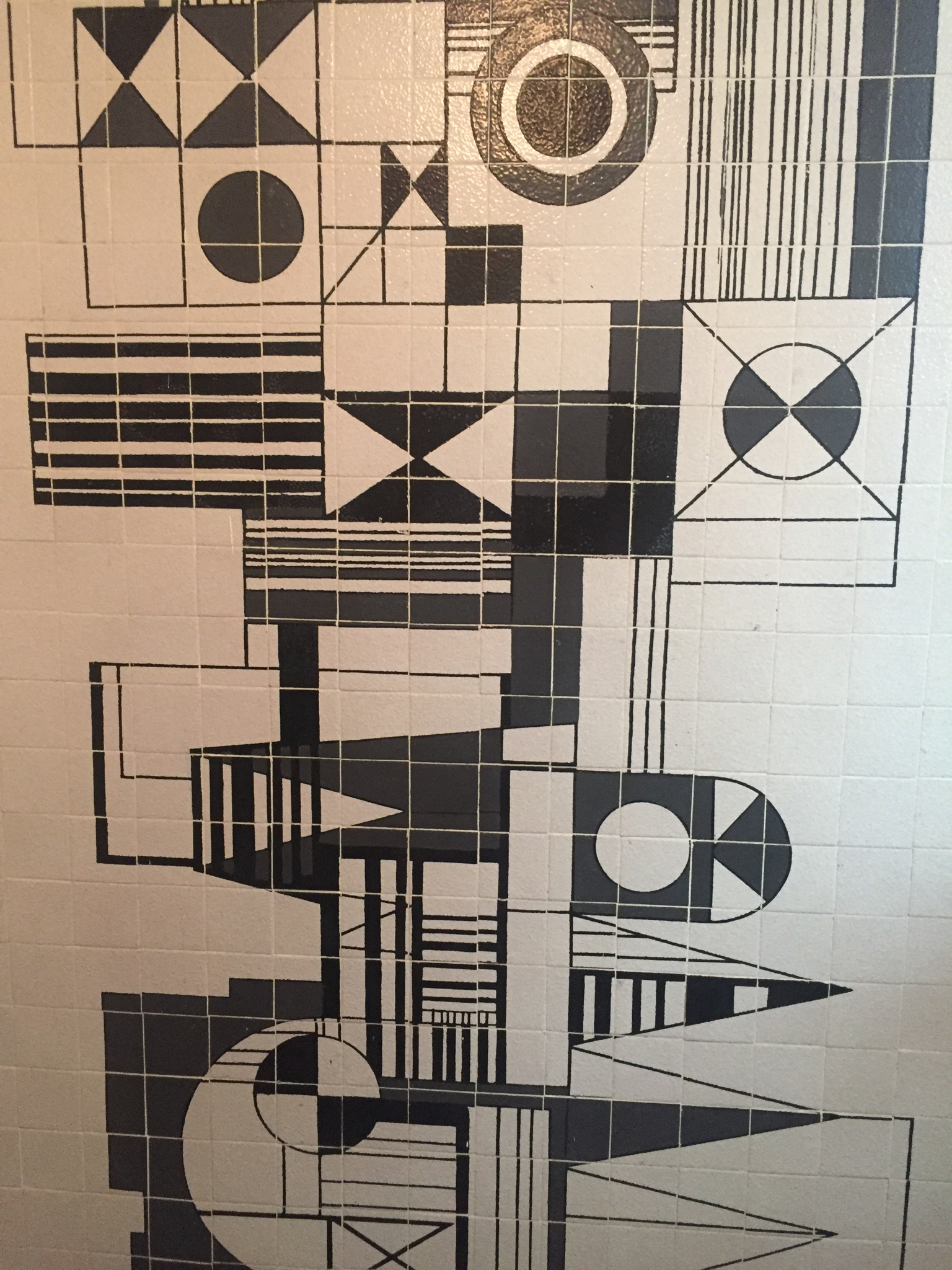

The story of the San Francisco Maritime Museum, a hidden San Francisco gem, is not just one of architecture and design although that is what pops when you walk in the subterranean Ghirardelli Square-adjacent entrance. Looking out over the historic seafaring vessels of the Hyde Street Pier and the crescent shaped beach that could easily be mistaken for Miami, a visitor is struck by the graciousness of this temple to the history of West Coast Maritime History, rich with exhibits that speak of the life of the people who made their living at sea. Unlike the more famous Coit Tower however, also a product of WPA largesse, the Maritime Museum has been very much under the national radar until now. Built in 1939 jointly by the WPA and the City of San Francisco as a bathhouse, the museum is part of a National Park Service Maritime Historical Park that highlights the city's connection to the sea.

Though the exhibits fascinate, inevitably, what thrills are the sublime murals, tilework and paint fantasia that are the work of WPA artists, each with a very different background whose work combines to make this space as dynamic and important as any art moderne building in the world.

It is the characters and practices of these artists, their personal histories and lives, that make this building very special, easily as impressive as the Coit Tower. This weekend, the Museum reopens with a second floor of maritime themed murals which complement the first floor’s showier ones and a third floor of exhibits tracing the history of the building.

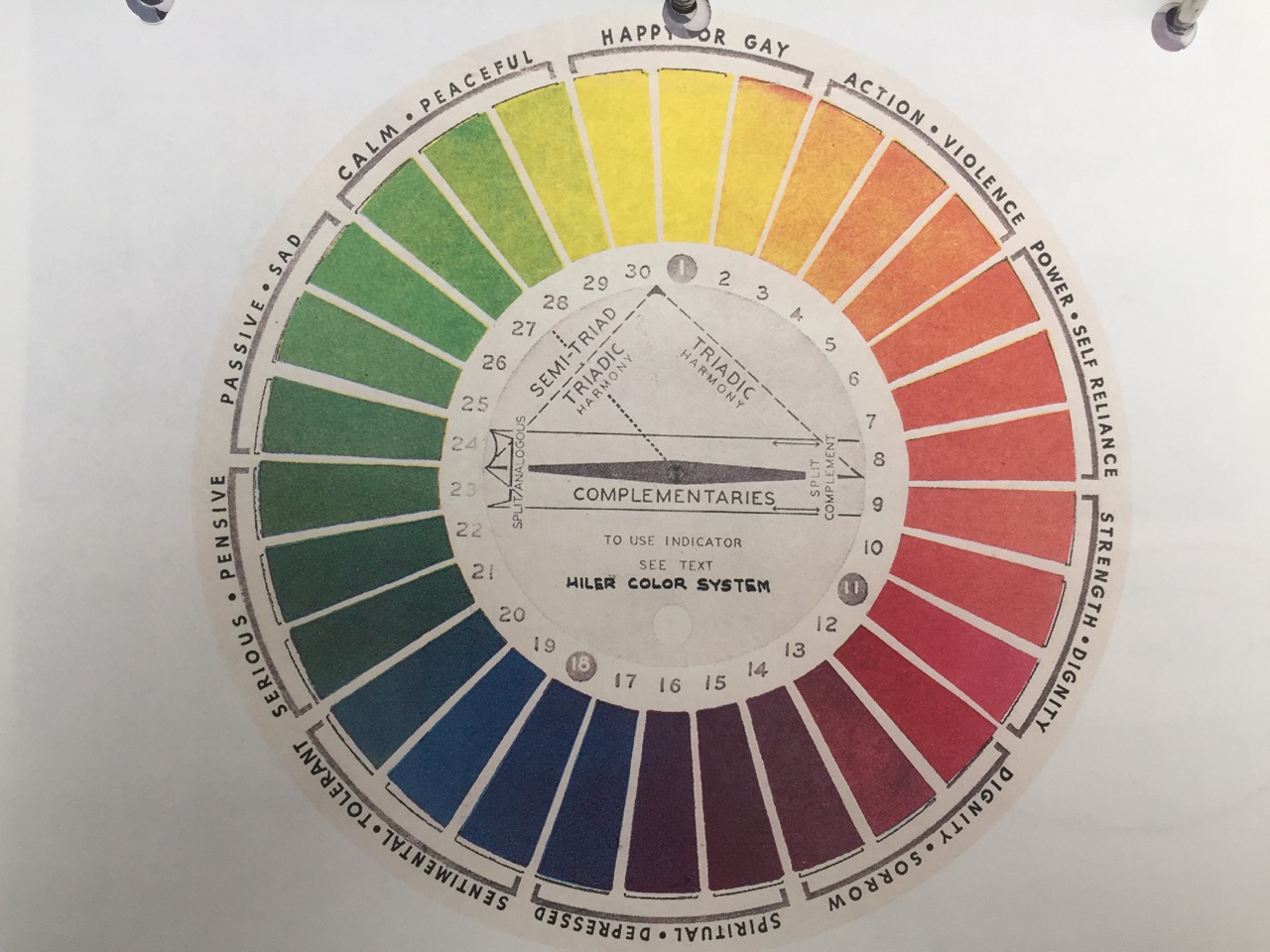

The whole project came to fruition over more than four years under uber-artist Hilaire Hiler who not only did the phantasmagoric first floor murals of the Lost Cities of Atlantis and Mu but supervised the other floors and artists and was the liaison to the architect. Hiler, a Jewish, 6 foot hulk from Minnesota who had his ears pinned back in an effort to appear smaller, was an American artist and color theoretician, a polymath who also wrote a bibliography of costume, worked as a set designer and jazz musician and whose psychoanalytic training became the underpinning of much of his work. He attended RISD and became one of the many Parisian expats, befriending Henry Miller and Anais Nin and Hemingway among others at the Jockey Club in Paris where he was a host and was often seen out and about with his pet monkey. His ‘neonature' theories about art found supporters in Miller and William Saroyan and one ceiling, the Prismatarium” is an ode to his color theory in which he proposed that color and the human psyche interact to enhance creativity. He had a long, eccentric and distinguished career including a stop in Hollywood and a collaboration with Rene D'Harnoncourt in San Francisco. He was authoritarian but respected his fellow artists as they collaborated on the design of the over 20,000 square feet of the elegant building.

Sargent Johnson, once a prominent black sculptor, painter and ceramicist and Communist of African American, Cherokee and Swedish descent who designed the mosaic tile murals was inspired by the work of Diego Rivera, Jose Orozco and David Siquieros.. His mosaic tile murals in shades of sea greens which grace the rear exterior deck overlooking the bay and his green carved slate which adorns the building entrance are further delights. Johnson had been orphaned as a child and grew up in asylums. He was born in the east but came to San Francisco to study and was employed by the WPA on a number of projects in a supervisory role. He had a small retrospective in Oakland in the 70s. He is lumped in with the Harlem Renaissance but in fact made his own way in the west. He was an artist who wanted above all 'to show the Negro to himself" even though he was half white.

Richard Ayer was charged with the newly refurbished second floor murals. The themes are nautical like puzzles which refer to abstractions of boat rigs, pressure points, wave patterns, plimsall, davits, signal rockets, naval arches, wireless hookups interspersed with wave forms, fish, spars, sea fowl. There are 5 shades of marine color and abalone shells in the terrazzo floor. Ayer used a novel technique called Polychrome Bas-Relief which allowed for raised areas depicting anchors, coral beds and birds. Artist Shirley Staschen, who had also done the WPA murals at the Coit Tower worked on the second floor murals with him.

Despite the fact that the WPA was meant to give work to American artists, many immigrants got involved when specialities were called for. An Egyptian tile worker custom cut and lay the tilework which was fabricated locally. Anna Medalie, Russian-born, assisted in the gold leaf and glazing on the first floor. (Women were largely equal partners at the WPA.) Benjamin Bufano, an Italian did most of the free standing sculpture. The socio-political values of the artists mandated that the space be open to the "public". They protested and walked off the job when they feared it might become too exclusive.

The basement or ground floor was the beachgoers entrance, through turnstiles and a newly invented system of sanitization including foot baths and automatic sensors that turned on the showers, stainless baskets to keep clothing, one room each for boys, girls, women, men.

Upstairs a radio room with vintage equipment has been reconstructed.

The structure, once referred to as a ‘Casino’ at which elegant parties and dinners were often held has gone through a number of iterations, but is now a monument to the life of the sea--the seductive, watery depths below abundant with marine life, the boats and tools of the trade at eye level--and to modernity, and to the WPA and its profound importance in our cultural history.This whole notion of public access and innovation is a testament to the way the federal government, when its working properly, can utilize the arts for the benefit of the public as no other entity can. The Park Service has been working for years on this new restoration and I could not think of a finer place for my tax dollars.

Images courtesy National Park Service, San Francisco Maritime Museum and the author

Goddesses at the Met

Inlaid with rubies in her eyes and navel as was the occasional special custom for Mesopotamian deities, this petite, exquisite 1st century BC-1st century AD standing nude statue in the Met Museum’s World Between Empires show of Middle Eastern treasures—and their horrific destruction by Isis--raises questions of divine identity. Is she a Greco-Roman Venus goddess of beauty and love or, as one curator suggests, Ishtar of Babylon who was closer to home? One other similar example of this kind of statue lay on her side easily recalling the many Olympias of the 19th century. Having just attended a Paola Antonelli salon at MoMA on ‘White Men”, I wondered why alabaster queens were the symbol of a middle eastern cultures? The statue is on loan from the Louvre where even in her diminutive state she could outshine the Mona Lisa

Images courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

White Men: a MoMA salon confronts the status quo

On the heels of Donald Trump’s almost vindication by the special prosecutor, curator Paola Antonelli’s Salon at MoMA about White Men held a special charge. One panelist, Whitney Dow is making films and interviewing only white men so they are not afraid to speak out. This image was offered by panelist Aruna D’Souza as a more ironic version of co-panelist Rich Benjamin’s slicing and dicing of white men into four categories: entrepreneurs, environmentalists, working men and minstrels with examples--besides Trump-- like Beto O’Rourke, who in his opinion are allowed to fail upward as no others. As was pointed out by almost all the speakers, white guys are still running and populating things--Silicon Valley, Washington, the Environment, Wall Street, Museums and Culture, and so it takes a lot of heft to move them from their special, centuries-long perch on high. The artist, Pastiche Lumumba, has nailed it in a “Woke, Gentrifyer Starter Pack” with copies of the right magazine, the right beer, the right tech, the right music….etc. It was a rare humorous moment in an evening which shone a light on privilege, race, gender. It’s very hard in the art world right now to escape this kind of categorization which I understand comes from a place of deep disaffection with the way things are. (I repost Paola’s reading list) As a white woman, too, I’m hardly exempt but I can speak to more personal issues having spawned four of them. I once wrote a whole book about having felt like I landed on an alien planet and barely lived to tell the tale.

Reading List and image courtesy of Paola Antonelli, MoMA Salons

Discovering Masculinity & White Identity

-Bazelon, Emily, White People Are Noticing Something New: Their Own Whiteness, The New York Times Magazine (06.13.2018

-Fortin, Jacey, Traditional Masculinity Can Hurt Boys, Say New A.P.A. Guidelines, The New York Times (01.10.2019)

-McGill, Andrew, Why White People Don’t Use White Emoji, The Atlantic (05.09.2016)

-Roberts, David, American white people really hate being called “white people”, Vox (07.26.2018)

-Whitaker, Robyn J., Jesus wasn’t white: he was a brown-skinned, Middle Eastern Jew. Here’s why that matters, The Conversation (03.28.2018)

-Yancy, George, #IAmSexist, The New York Times (10.24.2018)

-Harmful masculinity and violence, American Psychological Association (2018)

White Male Entitlement

-Cole, Teju, The White-Savior Industrial Complex, The Atlantic (03.21.2012)

-Fleming, Peter and Rhodes, Carl, CEO pay is more about white male entitlement than value for money, The Conversation (07.23.2018)

-Hall, Ronald E., Entitlement Disorder: The Colonial Traditions of Power as White Male Resistance to Affirmative Action, Journal of Black Studies, 34:4, 562-579 (03.2004)

-Keltner, Dacher, Sex, Power, and the Systems That Enable Men Like Harvey Weinstein, Harvard Business Review (10.13.2017)

-Lissner, Caren, Men are Killing Thousands of Women a Year for Saying No, Dame (10.24.2017)

-Rosner, Helen, Mario Batali and the Appetites of Men, The New Yorker (12.13.2017)

Maintenance of White Privilege & Benefit of the Doubt

-Lerer, Lisa, The Privilege of Being Beto, The New York Times (03.11.2019)

-McIntosh, Peggy, White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women's Studies, Wellesley College Center for Research on Women (1988)

-Onion, Rebecca, Automatic for the People, Topic Magazine (2018)

-Stack, Liam, Light Sentence for Brock Turner in Stanford Rape Case Draws Outrage, The New York Times (06.06.2016)

-Wurtenberg, Nathan, Gun Rights are about keeping White Men on Top, The Washington Post (03.09.2018)

-Yancy, George, Dear White America, The New York Times (12.24.2015)

Power & Normativity

-Amatulli, Jenna, Donald Glover Needed ‘White Translator’ To Convince FX To Allow ‘N-Word’ In ‘Atlanta’, HuffPost (02.27.2018)

-Friedman, Vanessa, Fashion’s Woman Problem, The New York Times (05.20.2018)

-Golliver, Ben, LeBron James calls NFL owners 'old white men' with 'slave mentality' toward players, Chicago Tribune (12.22.2018)

-Grigsby Bates, Karen, 'A Chosen Exile': Black People Passing In White America, NPR (10.07.2014)

-McCarron, Meghan, When Male Chefs Fear the Specter of ‘Women’s Work’, Eater (11.30.2017)

-Walker, Tim, Quentin Tarantino accused of ‘Blaxploitation’ by Spike Lee... again, Independent (12.26.2012)

White Men in the Workplace

-Cain Miller, Claire; Sanger-Katz, Margot; Quealy, Kevin, The Top Jobs Where Women Are Outnumbered by Men Named John, The New York Times (04.24.2018)

-Dishman, Lydia, White men still hold the most leadership positions in tech, Fast Company (06.25.2018)

-Jones, Stacey, White Men Account for 72% of Corporate Leadership at 16 of the Fortune 500 Companies, Fortune (06.09.2017)

-Weber, Lauren, White Men Challenge Workplace Diversity Efforts, WSJ (03.14.2018)

-White, Gillian B., There Are Currently 4 Black CEOs in the Fortune 500, The Atlantic (10.26.2017)

White Male Anxiety & Perceived Discrimination

-Dr. Agarwa, Pragya, Unconscious Bias: How It Affects Us More Than We Know, Forbes (12.03.2018)

-Berman, Jillian, When a woman or person of color becomes CEO, white men have a strange reaction, MarketWatch (03.03.2018)

-Berman, Jillian, White men who can’t get jobs say they’re being discriminated against, MarketWatch (06.17.2018)

-Blow, Charles M., White Male Victimization Anxiety, The New York Times (10.10.2018)

-DiAngelo, Robin, White Fragility (Chapter), International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3:3, 54-70 (2011)

-DiMuccio, Sarah and Knowles, Eric, How Donald Trump appeals to men secretly insecure about their manhood, The Washington Post (11.29.2018)

-Haider, Mischa, The Next Step in #MeToo Is for Men to Reckon With Their Male Fragility, Slate (01.23.2019)

-Massie, Victoria M., Americans are split on "reverse racism." That still doesn't mean it exists, Vox (06.29.2016)

-Norris, Michele, As America Changes, Some Anxious Whites Feel Left Behind, National Geographic Magazine (04.2018)

-Price, S.L., Whatever Happened to the White Athlete?, Vault, Sports Illustrated (12.08.1997)

-Bird: NBA 'a black man's game', ESPN (06.10.2004)

White Male Pride & White Male Rage

-Cep, Casey, The Perils and Possibilities of Anger, The New Yorker (10.15.2018)

-Deitsch, Richard, Anger Therapy in his Autobiography John McEnroe Comes Clean about his On-Court Behavior and Off-Court Anguish, Vault, Sports Illustrated (06.24.2002)

-Fortgang, Tal, Why I'll Never Apologize for My White Male Privilege, Time (05.02.2014)

-Friedersdorf, Conor, Does ‘White Male Rage’ Exist?, The Atlantic (10.10.2018)

-Krugman, Paul, The Angry White Male Caucus, The New York Times (10.01.2018)

-Newman, Brooke, The Long History Behind the Racist Attacks on Serena Williams, The Washington Post (09.11.2018)

-Schwartz, Alexandra, Brett Kavanaugh and the Adolescent Aggression of Conservative Masculinity, The New Yorker (09.27.2018)

Insecure Responses to our First Black President

-Coates, Ta-Nehisi, The First White President, The Atlantic (10.2017)

-Edsall, Thomas B., The Fight Over Men Is Shaping Our Political Future, The New York Times (01.17.2019)

-Lopez, German, The past year of research has made it very clear: Trump won because of racial resentment, Vox (12.15.2017)

-MacWilliams, Matthew; Nteta, Tatishe; Schaffner, Brian F., Explaining White Polarization in the 2016 Vote for President: The Sobering Role of Racism and Sexism, presentation at the Conference on The U.S. Elections of 2016: Domestic and International Aspects, January 8-9, 2017 (2017)

-Serwer, Adam, Trumpism Is ‘Identity Politics’ for White People, The Atlantic (10.25.2018)

A ‘Rebranding’ of White Male Identity

-Benjamin, Rich, The Trumpist White Minstrel Show, Los Angeles Times (10.27.2018)

-Blow, Charles M., ‘The Lowest White Man', The New York Times (01.11.2018)

-Gold, Michael, ‘I Just Love White Men’: White Man Aims Racist Rant at Columbia Students of Color, The New York TImes (12.11.2018)

-Hesse, Monica, How should we talk about white men today, The Washington Post (02.13.2019)

-Mishra, Pankaj, The Religion of Whiteness Becomes a Suicide Cult, The New York Times (08.30.2018)

-Percy, Jennifer, The Life of an American Boy at 17, Esquire (02.12.2019)

Policing the Bounds of the White Patriarchy

-Anderson, Elijah, “The White Space”, American Sociological Association, Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 1:1, 10–21, (2015)

-Gilio-Whitaker, Dina, Settler Fragility: Why Settler Privilege Is so Hard to Talk About, Beacon Broadside (11.14.2018)

-Harris, Cheryl I., Whiteness as Property, Harvard Law Review, 106:8, 1707-1791 (1993)

-Menand, Louis, The Supreme Court Case That Enshrined White Supremacy in Law, The New Yorker (02.04.2019)

-Onwuachi-Willig, Angela, Policing the Boundaries of Whiteness: The Tragedy of Being out of Place from Emmett Till to Trayvon Martin, Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository (2017)

-Patton, Stacey, White Women aren't Afraid of Black People, They want Pretty Power, Dame (07.30.2018)

-Wildman, Stephanie M.,The Persistence of White Privilege, Washington University Journal of Law & Policy (01.2005)

The White Male Online

-Angwin, Julia and Grassegger, Hannes, Facebook’s Secret Censorship Rules Protect White Men From Hate Speech But Not Black Children, ProPublic (06.28.2017)

-Collin, Rowan and Petray, Theresa L., Your Privilege Is Trending: Confronting Whiteness on Social Media, Social Media & Society (05.17.2017)

-Donovan, Joan, How Hate Groups’ Secret Sound System Works, The Atlantic (03.17.2019)

-Iqbal, Nosheen, Donna Zuckerberg: ‘Social media has elevated misogyny to new levels of violence’, The Guardian (11.11.2018)

From White Supremacy Ideology to Violence

-Bouie, Jamelle, The March of White Supremacy, From Oklahoma City to Christchurch, The New York Times (03.18.2019)

-Bowles, Nellie, ‘Replacement Theory,’ a Racist, Sexist Doctrine, Spreads in Far-Right Circles, The New York Times, (03.18.2019)

-Coaston, Jane, The New Zealand shooter’s manifesto shows how white nationalist rhetoric spreads, Vox (03.18.2019)

-Garcia-Navarro, Lulu, White Supremacy And Terrorism, NPR (03.17.2019)

-Kaadzi Ghansah, Rachel, A Most American Terrorist: The Making of Dylann Roof, GQ (08.21.2017)

-Parrott, Joseph, R., How white supremacy went global, The Washington Post (09.19.2017)

-Pazzanese, Christina, Probing the roots and rise of white supremacy, The Harvard Gazette (03.18.2019)

-Singal, Jesse, Undercover With the Alt-Right, The New York Times (09.19.2017)

-Williams, Jennifer, White American men are a bigger domestic terrorist threat than Muslim foreigners, Vox (10.02.2017)

Watch

-Benjamin, Rich, WHITOPIA: An Improbable Journey to the Heart of White America, Youtube (01.25.2016)

-Blanco, Mykki, WYPIPO: Mykki Blanco speaks about race in whiteface, Dazed (08.23.2018)

-Dow, Whitney, Whiteness Project, ongoing

-Rankine, Claudia, The Fire This Time: Claudia Rankine on Whiteness as a Brand, The New Yorker Festival (10.12.2015)

-Welp, Michael, White Men: Time to Discover Your Cultural Blind Spots, TEDxBEND (07.06.2017)

-Videos Show a Collision of 3 Groups That Spawned a Fiery Political Moment, The New York Times (01.22.2019)

-What's Killing America's White Men? BBC News, BBC News (10.18.2018)

The Brant Foundation reminds when art was the thing

In the midst of all the brouhaha about architecture gone wrong from coast (Hudson Yards) to coast (Lacma), the new Richard Gluckman building for the Brant Foundation in New York stands as a model of discretion and an excellent showcase for art. Remember when the art was the thing? The ceiling pool that greets you in the brick walled space feels like a dreamy light filled upside-down Turrell rather than a gimmick, you’re underwater without having to hold your breath. Gluckman has taken many inspirations from the mid century (Quincy Jones?)—the mullioned windows, the white birch landscape, the decomposed granite hardscape—and the wood plank or brutalist ceilings (Mendes da Rocha?) and supersized them made them neater and grander, but still, dare I use this word, tasteful. The view from the top 4th floor in particular is neatly centered on a church spire and the Manhattan one sees is not the new pencil thin spires dotting the island but rather the humbler East Village of yore. The Basquiats are plentiful and look very well in the space, especially enchanting when hung salon style downstairs, and a friend and I calculated that he was only in his early twenties when many of them were painted. They feel electric —a young black prodigy whose time was over too fast communing with Walter de Maria who had repurposed a ConEd station for his studio. Basquiat’s capabilities as a wordsmith—he almost seems to playing a version of Jotto with himself—also come to the fore. It was a pleasure to like something so unreservedly for a change.

John Richardson dies at 95, a biographer of Picasso equal to his lifelong subject

The following is an excerpt from my Huffington Post piece on Volume III of Richardson’s Picasso biography.

…All the more reason then to be worshipful and impressed at the astounding work of John Richardson who has produced the third volume of his biography of Picasso, The Triumphant Years, published this week to great acclaim. Richardson’s unflagging erudition, meticulous reporting, insatiable digging, clever connections, and vast and deep personal knowledge of the players makes this series much closer to a performance piece of biography , the definitive text.

And because Richardson makes it perfectly clear with engaging narrative and precise scholarship how worthy his subject is, even those who have read about Picasso before will be newly swept away by the intricacies of this complex character. This is not, however, just a tome for insiders, though it helps to have a healthy interest in art and artists.

Richardson met Picasso while living with Douglas Cooper (who had himself wanted to write the biography) in the south of France and saw him regularly from the early fifties through the early sixties. He began by thinking he would write about the wives and mistresses of Picasso, the way the artist used art and sex, painting and making love, as metaphors for each other and how the style of his work changed as he changed women—volatile relationships that Dora Maar, herself one of the mistresses, characterized to him as ‘first, the plinth, then the doormat”. This was the template we used on the film, (WNET, Picasso, A Painter’s Diary) and it’s reductive and catchy, certainly one way to process the gargantuan archive when you only have ninety minutes.

But as Richardson himself says, “Picasso’s work is far too protean and paradoxical to be limited to a single reading.” And so he abandoned that seductive narrowcasting at the outset in favor of a much more comprehensive and penetrating approach.

One that would more or less take the rest of his life.

Richardson isn’t the first to devote most of his life to Pablo, as the volumes make clear. The Picasso bibliography includes everything from kiss and tells to scholarly treatises about the work and any number of memoirs and biographies. (Richardson is impatient and dismissive of some of these earlier efforts, calling them everything from “unreliable” to “rigamarole” or “fairy tale” to outright “wretched” or “sheer fantasy”.) But his end result is entirely different. Encyclopedic without being boring, any future artist’s biography, or really any biography, will inevitably have to step over Richardson’s very high bar.

Occasionally, biographers manage to be fans of their subjects for the duration. It’s hard to love someone unreservedly whom you come to know so intimately— Richardson doesn’t shy away from scandal, rather he is propelled by it, and sometimes, if this works to Picasso’s disadvantage, so be it. Looking at a life from the perspective of the warts and all can produce battle fatigue but at the end of the third volume (the ballets, the project for a memorial to Apollinaire, the bourgeoise life with Olga, the flirtation with Sara and Gerald Murphy, the rebellious hedonism of his attraction to the seventeen year old Marie Therese) with Picasso shrugging off Surrealism and heading for the shattering Guernica, one still feels Richardson’s magnificent enthusiasms for the moods, the settings, the entourages that may have influenced him; the motivations, the myth-busting, the sexual/historical/empirical digressions often taking us far afield only to bring us back a bit later with a much richer understanding of what made this man, and his world, tick.

The volumes look and are dense, (Volume 1 ranges from 1881-1906, Volume 2 from 1907- 1916 and Volume 3 from 1917-1932) but they are intensely readable—chatty, personal, with mini- biographies of others in the Picasso circle—so that we come to know just how convoluted and complex the roots of the art were with Pablo often devouring the hands that were feeding him. The tangents, however “vaut le detour” and are every bit as juicy as the three star view of the man himself. Often, Richardson makes patently clear, Picasso was conceptually leagues ahead of everyone else. But at times he was in debt to other geniuses who were his friends and competitors-Braque, Gaugin, Matisse, Seurat—and to the other protean talents from whom he freely stole(Manet, Ingres) ideas and images.

The normally heavy lifting of biography thus seems like gossamer in his hands, the facts arranged in such a way as to ease you on down the road with the tone of a confidence or a wink. The iconography of each important work is disarmingly traced, threading the personal and professional antecedents into one comprehensive whole. There are no sacred cows for Richardson—and like a cat he sneaks up and circles the truth and then pounces on it, explaining the artistic breakthroughs, the changes from one style to another, the sexuality and drugs which fueled some of them, and Picasso’s own drama-king ego that self-mythologized to the point that he came to believe in the stories too. As a myth debunker Richardson, however, is unsurpassed, adroit at peeling the layers: first, those of Picasso himself, then the second generation contemporary witnesses who often rewrote history, then the third generation anecdotal whispers, the fourth generation scholarly reckoning, and so on, often a daisy chain of prior confabulation.

Richardson leaves no dwelling, no voyage, no influence (the wonders he saw and appropriated into his own work), no woman, no friend , or enemy uncharted. One resists the tendency to makes lists only with difficulty: the houses (in Volume Three alone: Montrouge, rue la Boetie, le Gueridon, La Vigie, la belle Rose, la Haie Blance, Boisgeloup), the Women (madcap Fernande, lissome Eva, bourgeoise Olga, , sexpot Marie Therese, free spirited Francoise, imposing Jacqueline), the friends (Apollinaire, Cocteau, Jacob, Breton, Gertrude Stein, Stravinsky, Diaghilev) and the enemies and some that straddled the two camps, the Dealers (Kahnweiler, Rosenberg), the ballets (Parade, Tricorne, Pulcinella, Mercure, L’epoque des Duchesses, La Danse), the Museums, (besides Paris, Antibes, Barcelona and now Malaga) the Galleries, the retrospectives and exhibitions, the media (paint, sculpture, photography, poetry, collage, tapestry). All come under his watchful, painstaking and often bemused eye.

Richardson’s gift for language also has the added bonus of a mini-tutorial in French and Spanish slang —gratin (high society), bien couillarde (ballsy, or well hung), tertulia (group of friends).

And as far as wrangling goes, Richardson is unrivaled. Some of the images were a revelation to me; many classified or in private collections that were being carefully concealed at the time of the documentary but his long personal cultivation of so many of the Picasso personages has reaped its rewards and the astonishing selection of photographs from the Olga years in Volume Three is testament to this.

Richardson notes that for most of his life, Picasso was already in the spotlight, that the tributes and retrospectives one normally gets at the end had been ongoing since his twenties. Little details, why Picasso’s black was blacker than black (he added silver powder) or his relationship with Chanel (one night stands) make the reading lively. But it also helps to be reminded of his early genius, the sheer power of his intellectual and instinctive audacity—the breakthrough Demoiselles D’Avignon for example,was painted when he was 25!

In short, Richardson seems to have found a way to see Picasso plain while at the same time respecting his obviously century-dominating genius. Fernande, an early “official” mistress apparently said, “He who neglects me, loses me” and Picasso might well have intimated the same thing. Fear not, Richardson has made amply sure we won’t.

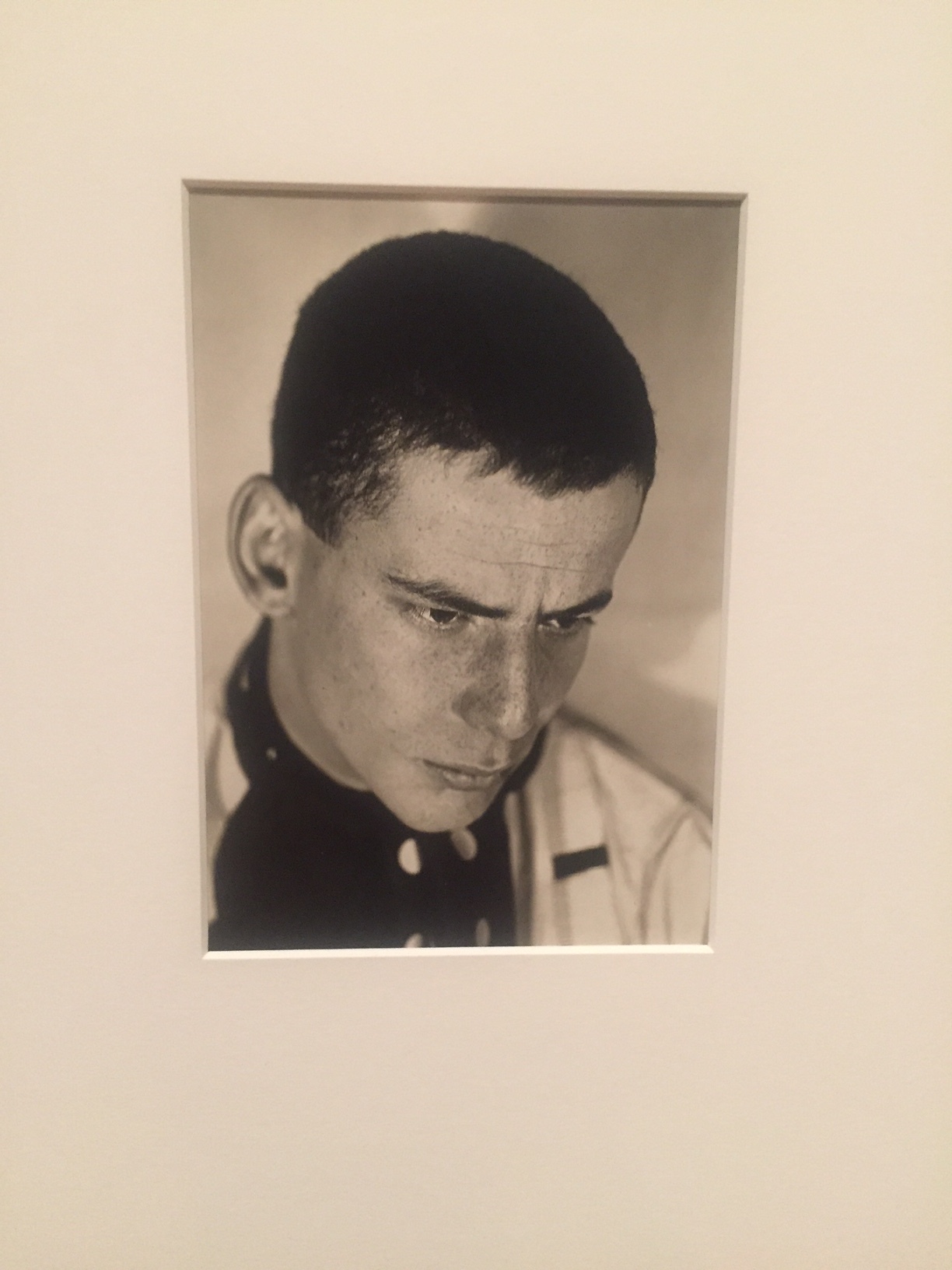

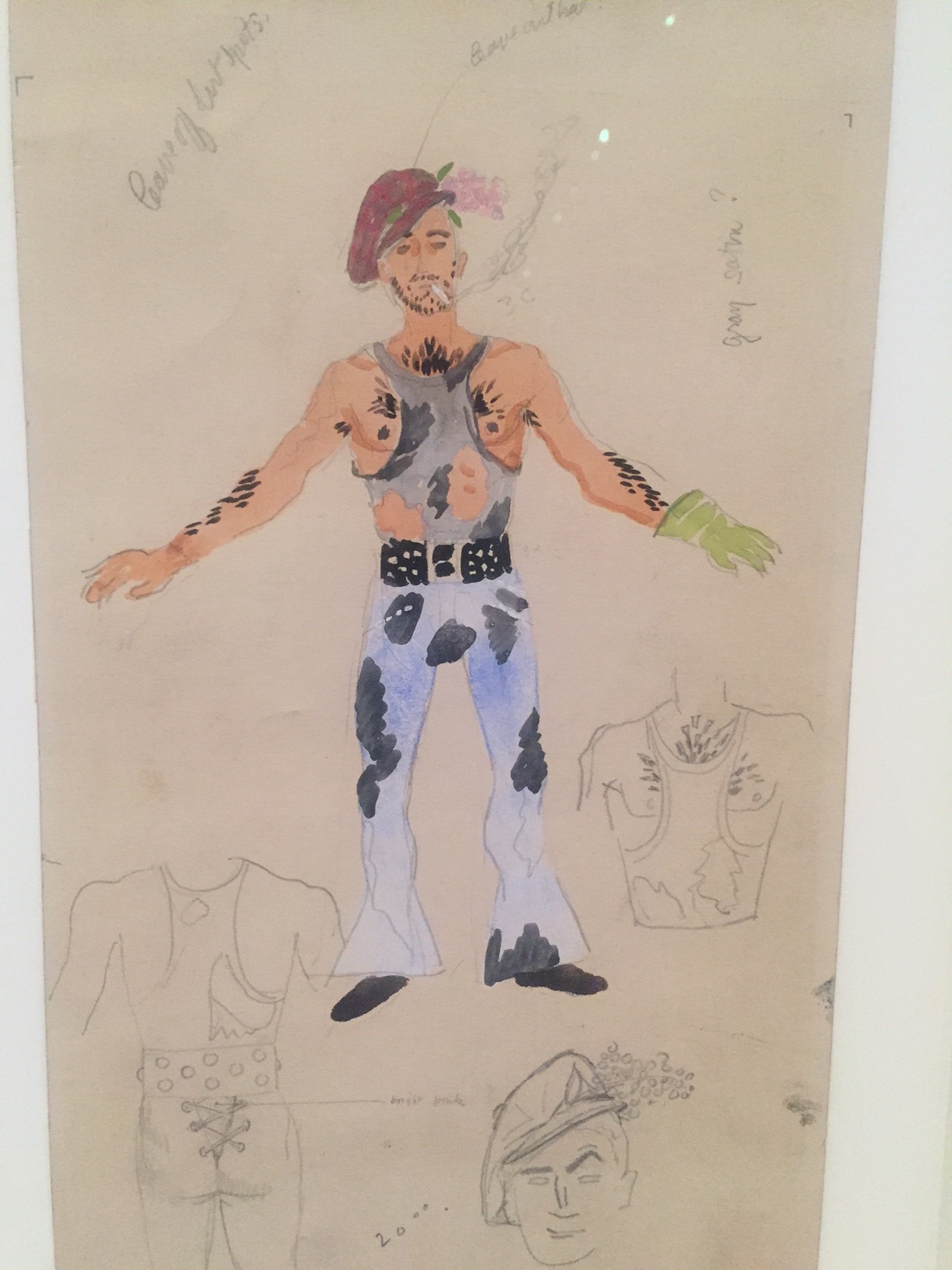

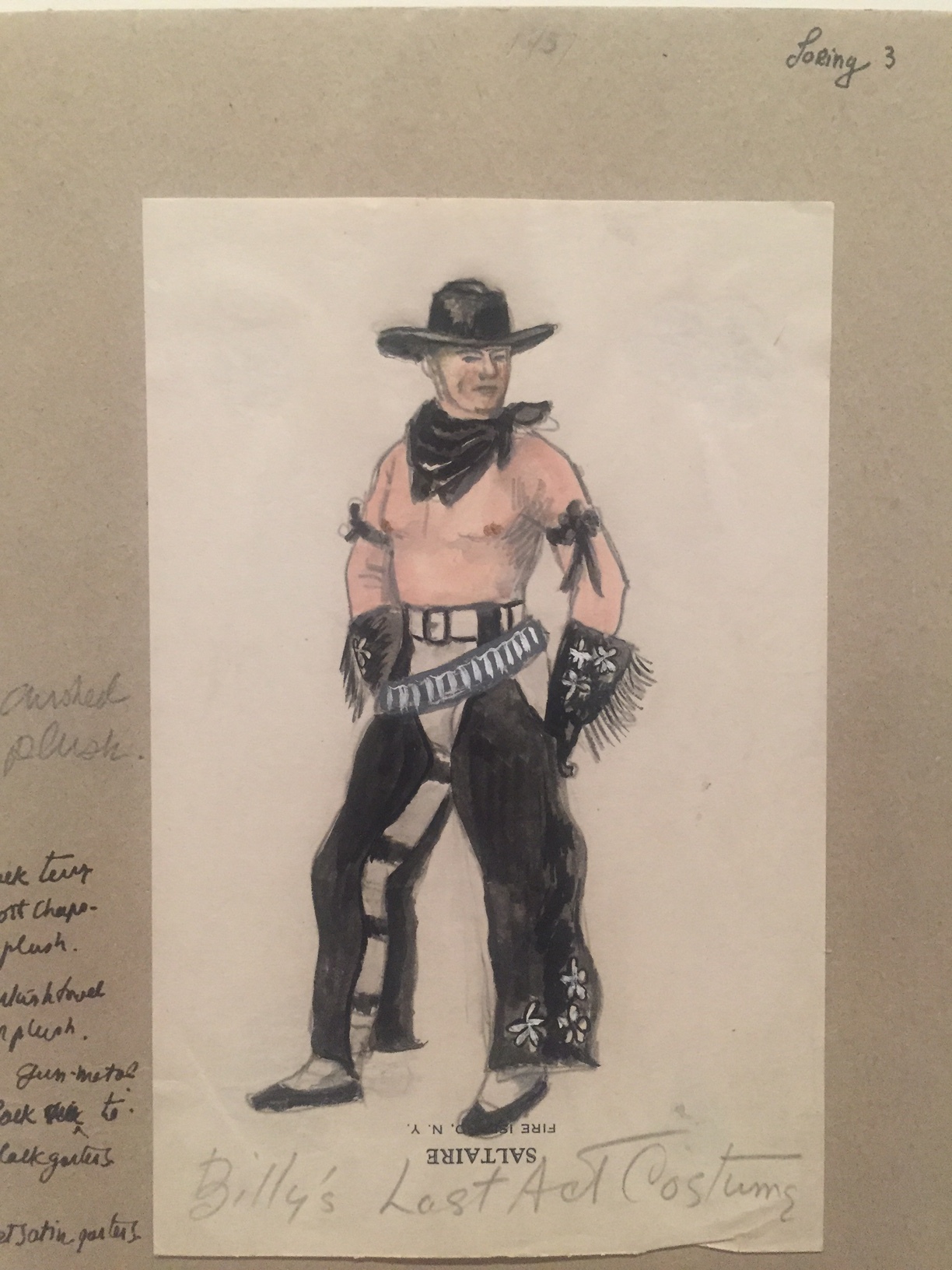

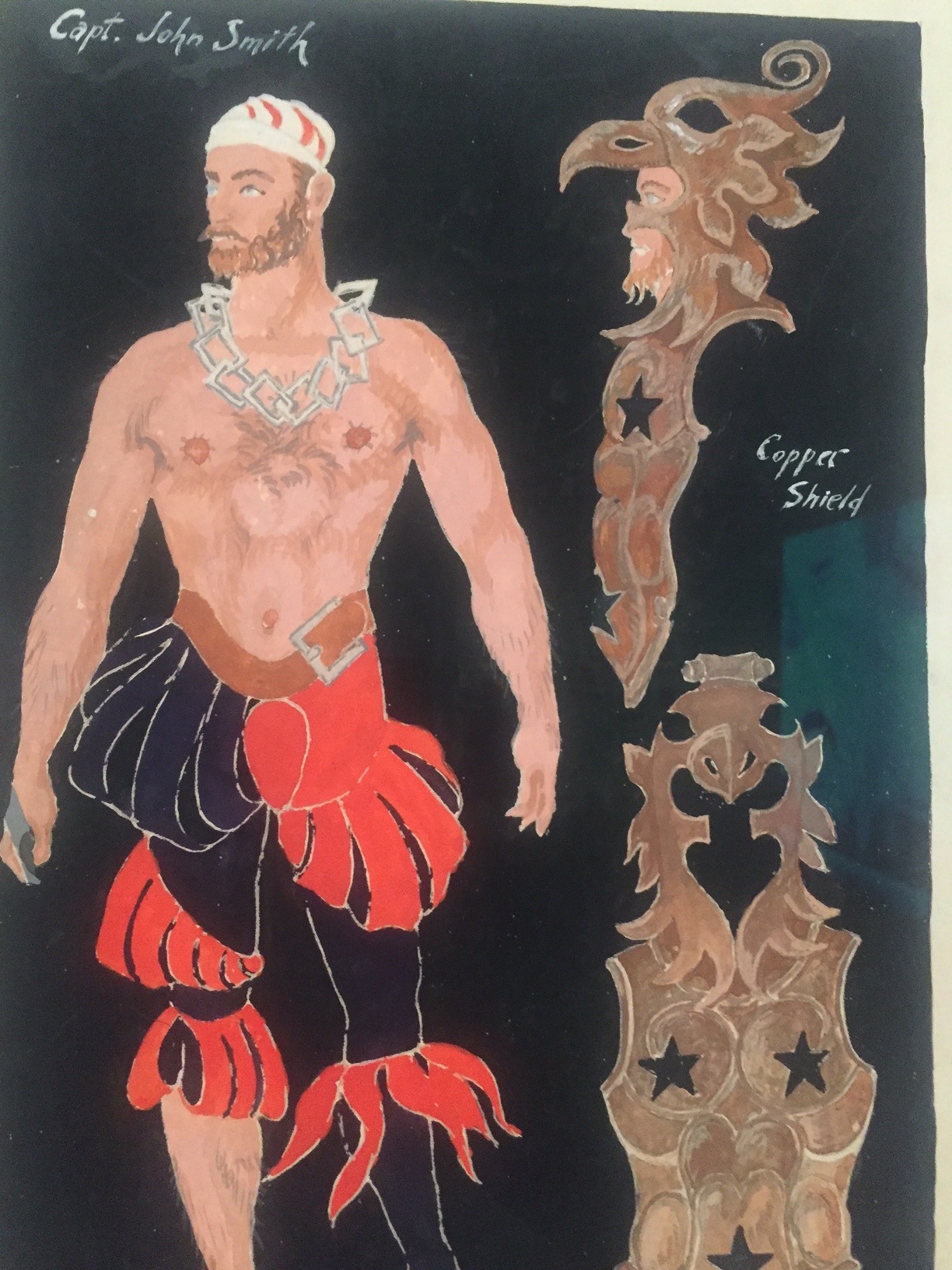

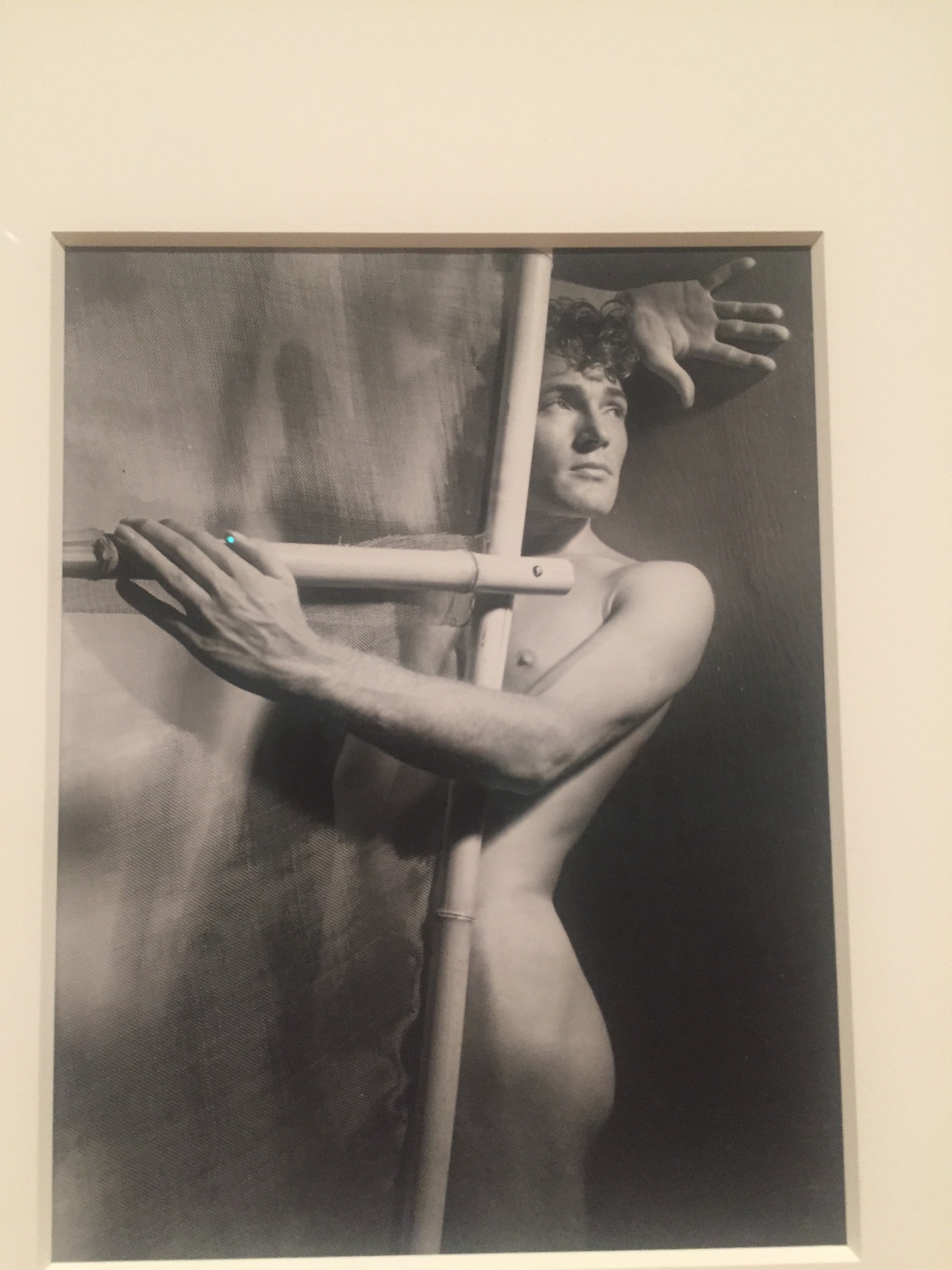

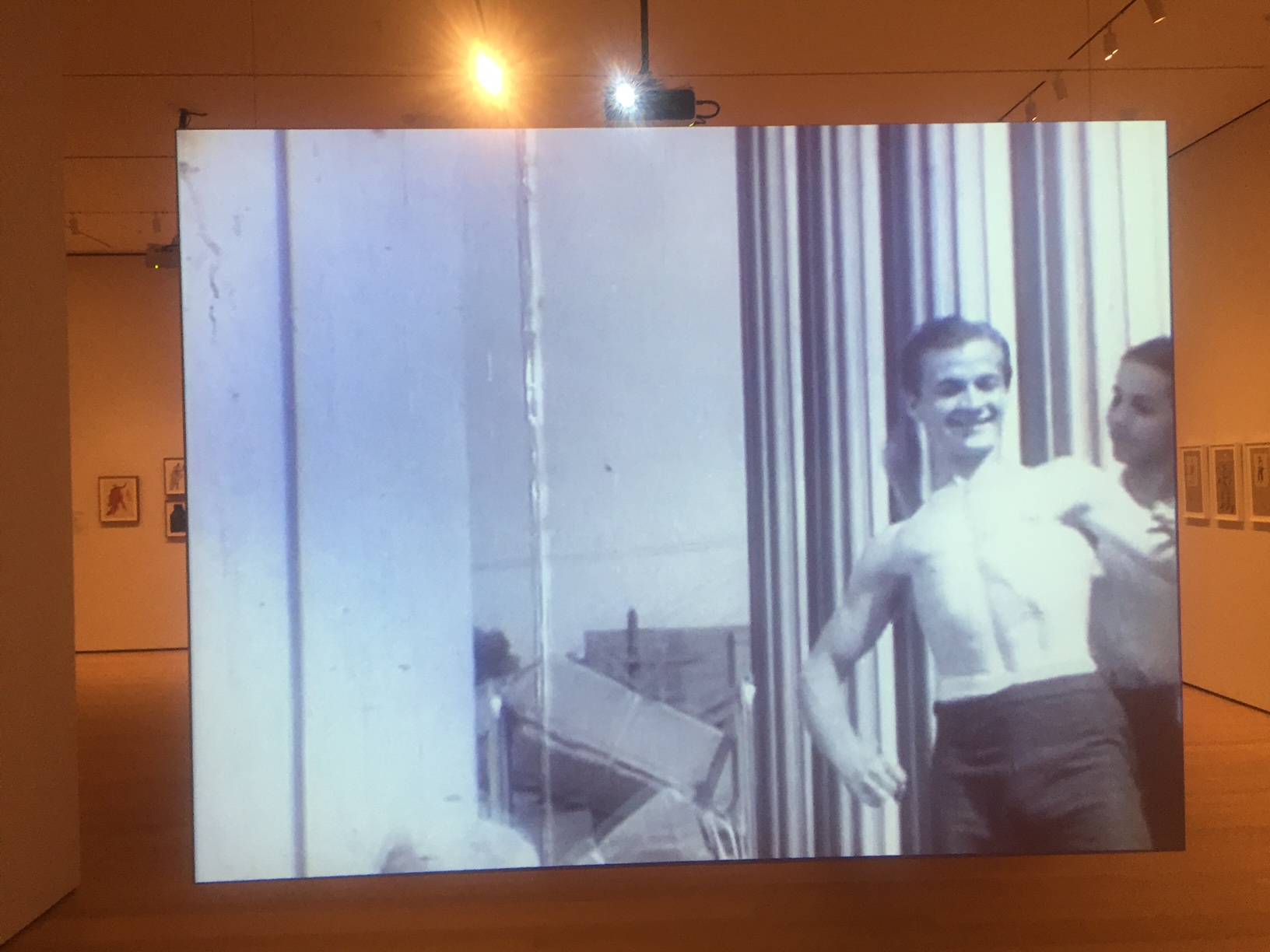

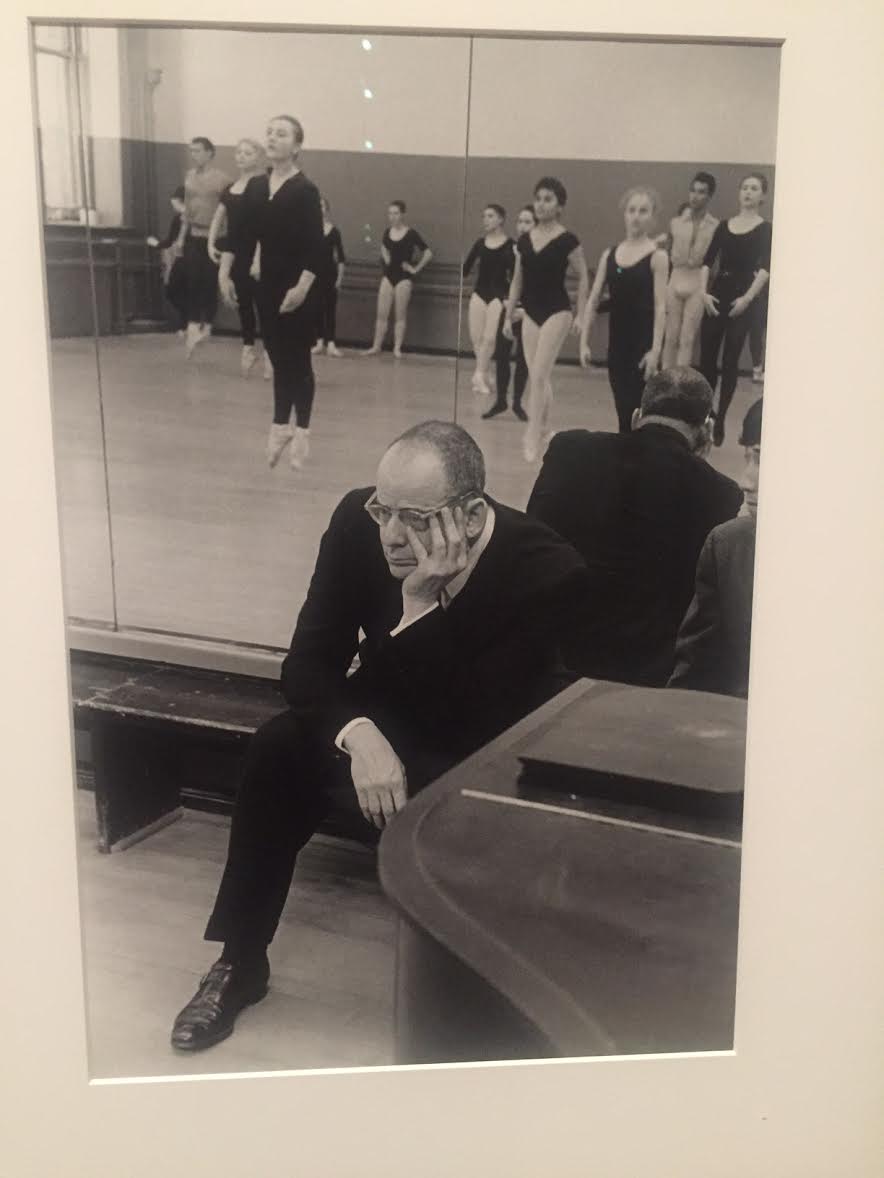

Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern

The Museum of Modern Art has exhumed its diverse archive of Lincoln Kirstein-iana in a new exhibition, Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern. We see his love for ballet, for art, for theater, for film, for photography, and for left-liberal causes.

I was in a class of 8 year olds at the school of American Ballet and it was Kirstein’s words in the brochure which had convinced my mother that a ballet career could, in the proper hands—e.g. Balanchine and his Russian Mesdames—be the equal of law or medicine.

He wrote he had his first coup de foudre for dance in the person of Tilly Losch who performed in Errante in a green satin evening dress with a twelve-foot train. A well-to-do, only semi-closeted Bostonian who became obsessed with ballet, Kirstein finally went to Europe as a young man, gathered his nerve, and asked Balanchine to open a school in America while at his fancy London hotel, far away from his family, surrounded instead by white-robed English beauties with plumes in their hair getting ready to be presented at Court.

But MoMA is eager to show the man in full. Besides being an impresario, he was also a polymath, a renaissance man, a multi-disciplinary scholar, and a fierce advocate for the creations and artists he cared about. He seized upon MoMA not long after its opening as the perfect repository for his many enthusiasms. This is both the exhibition’s unifying theme and its challenge. Kirstein was not as gifted a talent spotter in every medium as he was a ballet agent. Even there, it was the collaboration with Balanchine which made his work in that discipline so important. His passions did not always allow for the best judgment, in fact then-Director Alfred Barr was sometimes at pains to rein him in. Kirstein pushed MoMA in directions they may not at first glance have anticipated including a Dance and Theater department, not long-lived—which now, however, seems prescient as performance has entered the curatorial mandate at MoMA and at many museums..

He made many subsequent donations including a large collection of George Platt Lynes beefcake. As the very interesting catalog and the many costumes and designs showing off buff male torsos makes plain,homosexual connections were the genesis of some of Kirstein’s most important collaborations. (As a young summer intern in the Publications Department at MoMA, I did not know for example that former department head Monroe Wheeler had once lived in a threesome with Lynes and writer Glenway Wescott. Kirstein himself had lived in a threesome with his wife Fidelma and dancer Jose Martinez. Etc.)

The discursive and lively exhibition, curated by Jodi Hauptman and Samantha Friedman, can feel a bit kitchen-sinky by the last gallery. But it accurately reflects a febrile mind from which sprang much curiosity ,encouragement and leadership—backed up by dollars. Would that the patrons of today had the foresight and stick-to-itive-ness of this brilliant man.

The exhibition runs from March 17 - June 15 at the Museum of Modern Art. MoMA is also collaborating with the NY City Ballet for performances in their atrium. A companion exhibition on Jerome Robbins is at the Cullman Performing Arts Library at Lincoln Center.

Dorothea Tanning opens eyes and doors at the Tate Modern

Like Warhol, Dorothea Tanning, the subject of a new retrospective at the Tate, toiled first in advertising when she came to New York. She had been deeply affected by the groundbreaking MoMA Surrealism/Dada show of 1936 and her ads for Macy’s and others reflected this new awareness of the ability to disassociate body parts and imagery.

She herself was selected by her future husband Max Ernst—then married to Peggy Guggenheim—for a show of women artists at Guggenheim’s Art of this Century gallery when she returned from a stay in Europe. (Was this the moment of the Ernst-Tanning coup de foudre? A year later they were together) Georgia O’Keefe refused to be relegated to this show of ‘women artists” but Tanning accepted. When next invited to participate however in a women-only show in the 70’s second wave of feminism, like many creative women who had already made their own way (Mary McCarthy, Lillian Hellman et al) Tanning was also finally a refusnik. ‘Women artists,” she said, “There is no such thing – or person. It’s just as much a contradiction in terms as “man artist” or “elephant artist”. You may be a woman and you may be an artist; but the one is a given and the other is you.’

She had by then grown into a bold, incisive, self-confident practitioner of painting, poetry, sculpture, costumes and set design.

"Just put yourself in my place, George, " she wrote after she had, in a labor of love, produced the costumes and sets for Balanchine’s new ballet Night Shadow, supported by Lincoln Kirstein, "and you would cry too." Tanning was passionate about ballet, but her production had an unfortunately short shelf life when a new production by the Monte Carlo ballet appeared just a few years later. "I really thought all this time that I had helped to make it a good work, and lots of other people thought so too. I was proud to have worked with you to make such a pretty ballet and I felt it was a real collaboration of all 3 of us. But I suppose it’s a very complicated story and I don’t understand very well how these things work."

Tanning went on to work on other ballets and had plans for many more, but was thwarted by lack of funding and the nature of the collaborative process which stymied her as a solo practitioner .

I wonder what Tanning would have made of the many women-only international shows organized this year in response to #MeToo. Ghetto or Gift? The concurrent counter narrative solo exhibitions—besides Tanning (Ernst), Lee Miller(Man Ray) and Gala Eluard (Dali)—who have finally been removed from the rolls of the ‘muses’-only, tell a more complete tale.

The exhibition runs from February 27 to June 9, 2019 at the Tate Modern. All images courtesy of the Tate.

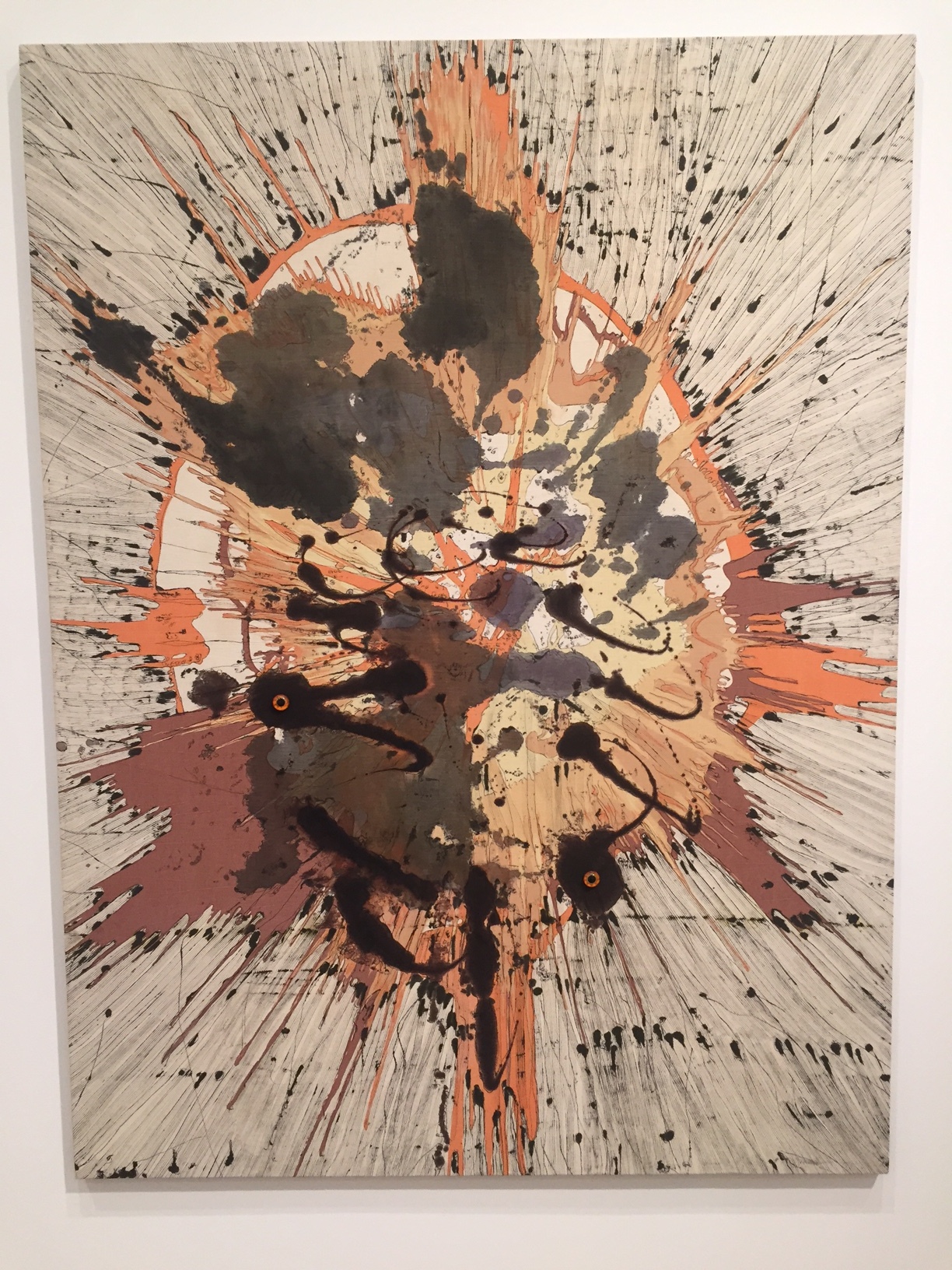

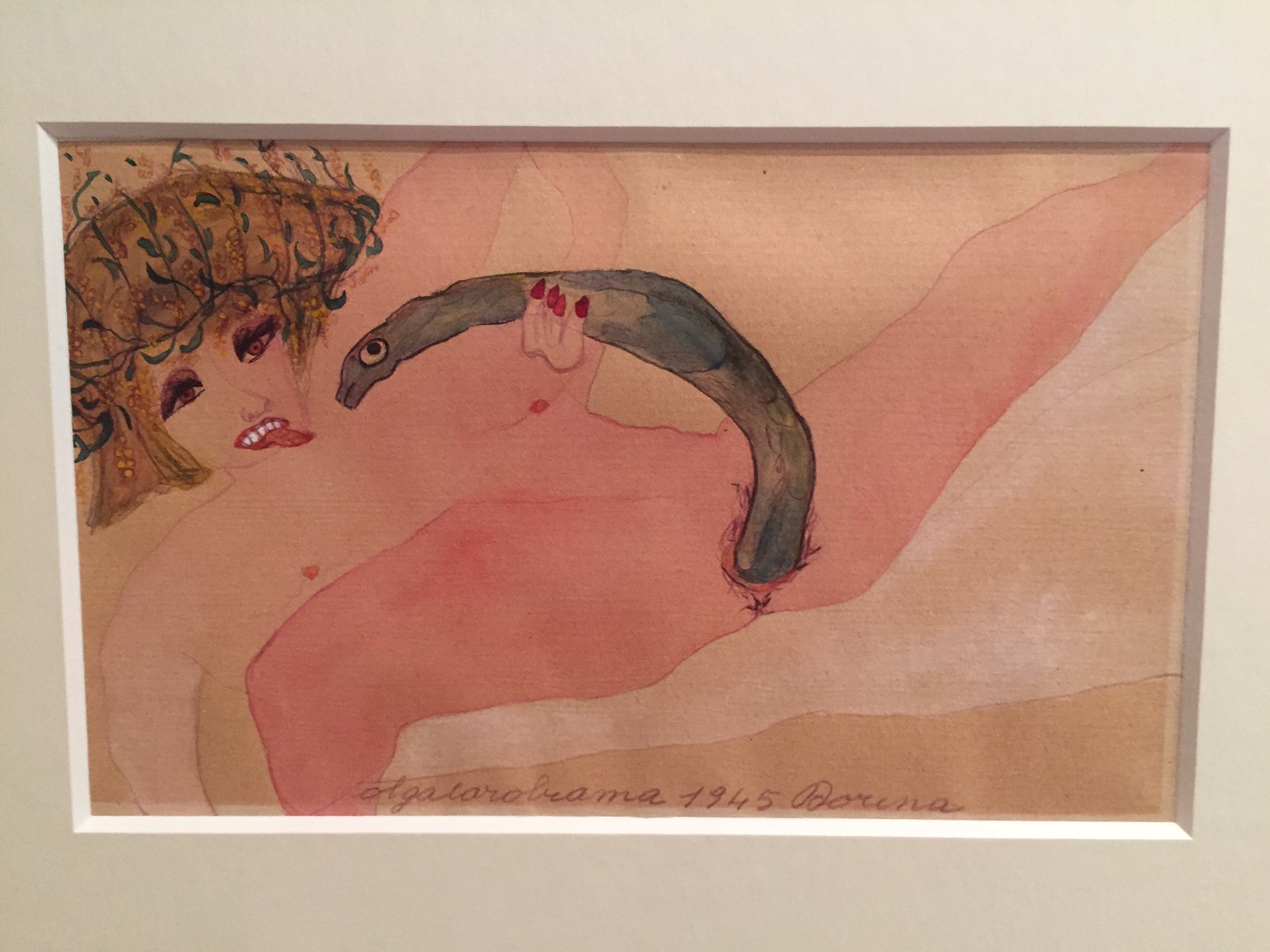

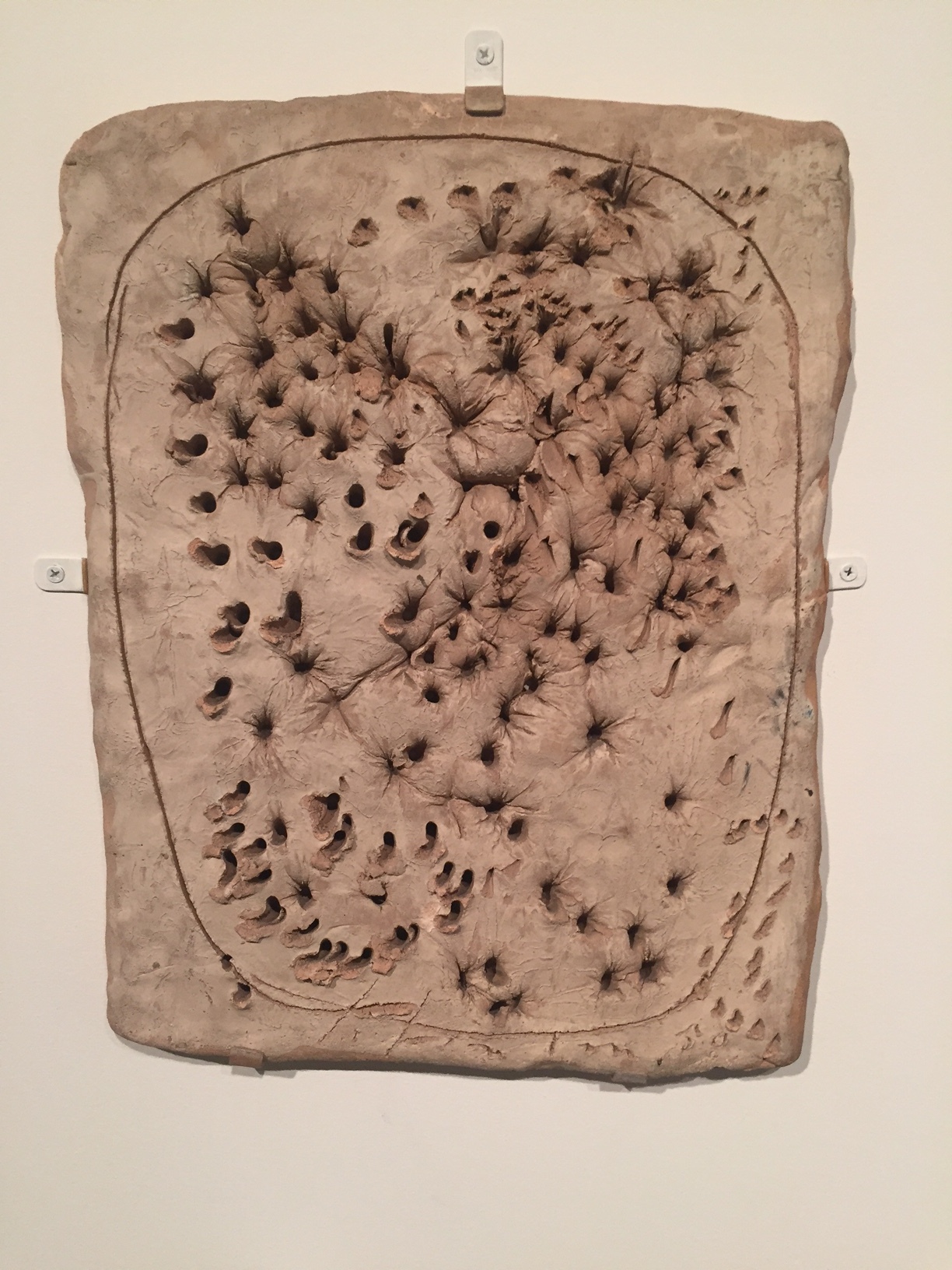

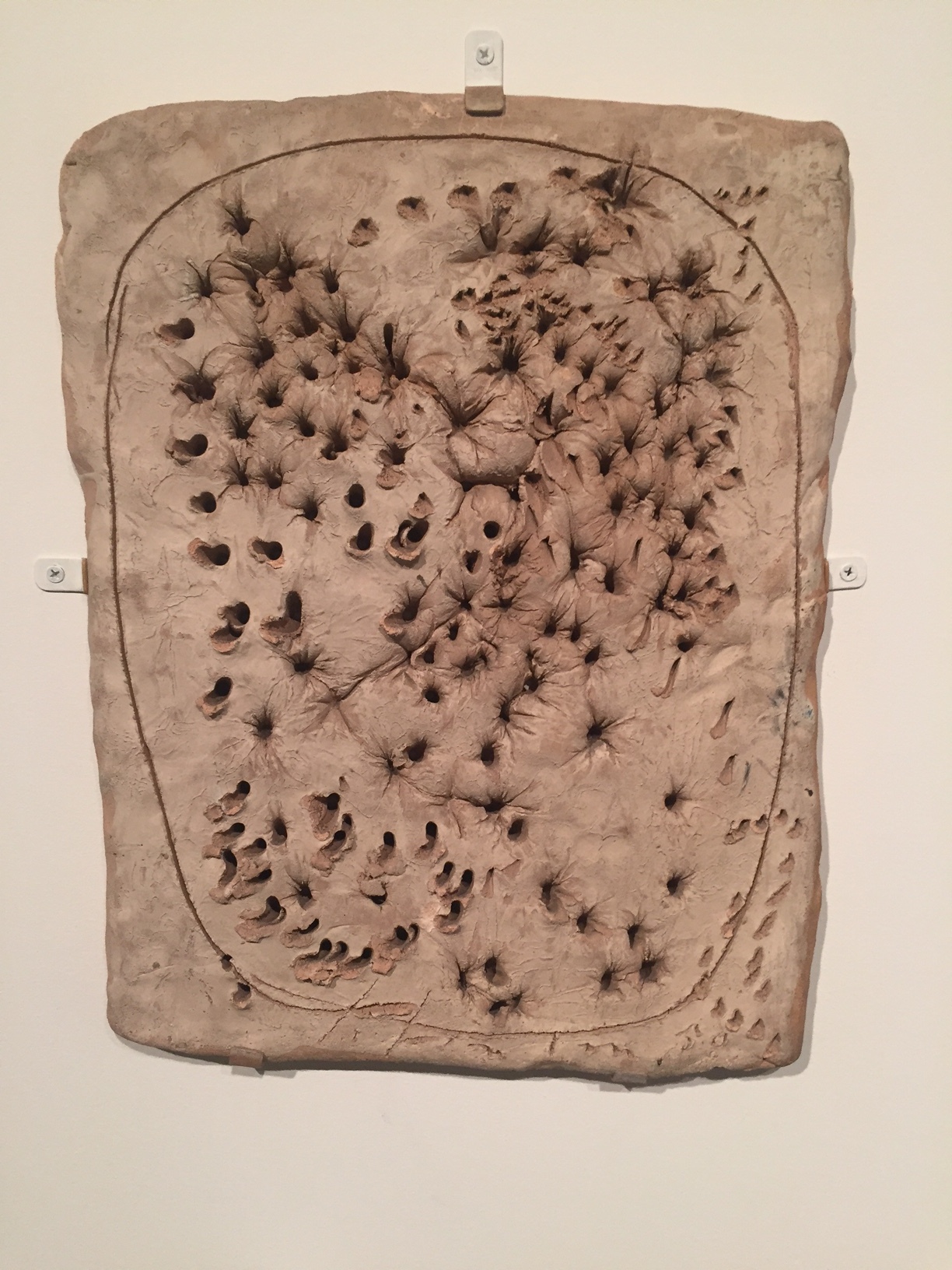

Carol Rama was not one for sitting pretty

Carol Rama was very much her own person and her own artist, but I could not help but be reminded of Alberto Burri when I saw her work. Both repurposed discarded materials in their canvases (Rama: syringes, tires; Burri: war cast-offs, plastics and sheet metals) making not-quite-paintings, not-quite-sculptures, emerging then with a third dynamic way of bricolage. Unlike Burri, she had little recognition until the end of her life: her work challenged erotic and gender norms. Rama’s current show at Levy Gorvy also includes Egon Schiele-esque delicate, erotic watercolors and pen and ink drawings which do not seem as if they could not have come from the same much more abrasive fount. "I didn't think I had the qualities for becoming an artist," she once said. "Beautiful women, prima donnas, beautiful people who speak several different languages, sitting and being charming.”

Bulletin from Brazil

Brazil has been much in the news. As if it weren’t enough that post-Olympic budget shortfalls, political corruption, Zika and crime had combined in a toxic brew, the recent election of Bolsonaro pointed up deep-seated philosophical fears and divisions much as the Trump election did in the US.

Brazilians in the creative sector have been trying to regroup, but in addition to the above they have faced devastating fires (the National Museum of Rio), burst dams, (Brumadinho adjacent to Inhotim art park), and the abolishment of the Ministry of Culture, which has been folded into a newly christened Ministry of Sport.

I finally returned recently to Brazil after a long absence. As a pre-teenage exchange student in the home of a wealthy Carioca family with whom my parents had briefly met and conspired late one night undoubtedly after too many caipirinhas, I had a decidedly one-sided view of the country. As a sheltered suburban girl, suddenly I was with a posse which had free reign—underage drinking and driving, dancing ‘till dawn on Ipanema. On the wild rides to mountain homes in Petropolis we passed favelas which made me mute— Brazil was my first third world country.

I returned ostensibly to study modernist architecture but my journey became a window into both politics and culture as a country’s built environment—and how it is respected— is closely aligned with the political imperatives of the day. In my view, this 20th century patrimony is as important as the pyramids are to Egypt. So many iconic structures are deteriorating and are without adequate fire protection. In Rio next year there will be a world architecture congress with government support which will address some of these issues—already a few of the most distinguished buildings are undergoing thorough, if protracted, preservation projects.

I arrived this time in Brasilia and went directly from the plane to drop my bags at the Niemeyer designed Palace Hotel, a quiet lakeside gem near the Embassy district. I had the impression of being on a stage set even though Brasilia is now a full-fledged metropolis. Inevitably, it is the show stopping Niemeyer federal buildings that still have pride of place. My first stop was to be the Alvorada Palace, the Brazilian White House, the Bolsonaro residence of only a few weeks’ duration. Military guards and street blockades warned that this would not be easy and, sure enough, even though I had given my passport number in advance (and Bolsonaro was in Davos), I learned that the palace, though previously accessible on certain dates, was now permanently closed to visitors. My architectural colleague (almost all my expert guides were organized by Superbacana) explained that, in his opinion, the house was Niemeyer’s most beautiful work in the city. I’m told this might change, but it was only the first of many heartbreaks of inaccessibility along my route

Nevertheless, my day with Oscar, as I came to think of it, was every bit as fulfilling as I had imagined. Brasilia is a resounding example of the political will of principally three men—Juscelino Kubitschek (President), Lucio Costa (planning) and (architect) Oscar Niemeyer— to build a utopian mecca for a new more central seat of Brazilian government in 1956 (it had been Rio)—in just four years. Though I generally am suspicious of superstardom in architecture, here I was grateful to have this body of monumental work on display. Yes, there were manifold issues around its construction in the middle of a largely rural province. As in the construction of Gibellina Nuova, Sicily, the visionaries marched to their own drum without consulting local inhabitants.

Highlights: on the Monumental Axis, the Itamaraty Palace with its splendidly thin arches, its central staircase, its Roberto Burle Marx garden; the National Congress with its pea green carpeting, brutalist hallway and starry-ceilinged legislative chamber, the Ministry of Justice with waterfalls emerging from its façade. On the residential axis, the elegant living spaces and muted colors of the Superquadras (these a true revelation), the brutalist, un-gated Mexican Embassy. (Our American Embassy has just announced a new project by Jeanne Gang. Thank goodness, as the walled, wired, hodgepodge mess there is an embarrassment. At least one good decision from the Trump State Department).

In anticipation of going to Salvador, Brasilia’s polar opposite, I took an Afro-Brazilian dance class at Steps. That revved me up for the multi-culti experience of that seaside city which keeps its clock—and its energy—on a time all its own.

Highlights: There is a Lele (Joao Lima) cathedral and city hall and other projects by Lina Bo Bardi, one in restoration (the museum) but others (a theater, a bar) in alarming stages of disrepair. I was very taken with the local branch of the Sarah Hospitals chain (LeLe was in the in-house architect), and a wonderful history museum, the Misericordia Hospital, evidence of the Portuguese wealth that existed when Salvador was an early capital. These are thankfully in pristine condition.

A contemporary architectural intervention into an adjacent palace made the Carnival Museum a dynamic space with video exhibits which—for the first time in my experience— give dance and music a founding place in the history of a country. However nothing was as thrilling as an actual afternoon Carnival rehearsal with Olodum, the largest of the Bloco Afros.

Though some claim they have become too commercial, their intense drumming and singing which revved up a crowd of locals and foreigners was entirely infectious and hardly disturbed by the defile of military police which marched through at regular intervals. ( In the town square, I saw other police routinely searching and harassing local youth. Is this a new Bolsonaro initiative or business as usual in Salvador?) Two new chic hotels are open near the waterfront (Fasano and Fera), but I stayed in the heart of the Pelourinho district at the faded but friendly Convento do Carmo which felt more in keeping with the city energy. Salvador was named one of the NYT 52 places to visit this year, but I would wait until fall as many things are under construction.

I was a lesser but still mournful victim of the giant dam disaster in Brumadinho as, despite pulling every string possible, I was not able to gain access to Inhotim, the marvellous contemporary art site just adjacent which, although not damaged, was closed in solidarity. I made lemonade by adding a stop outside Belo Horizonte at Pampulha, Niemeyer’s spectacular lakeside complex—again devised in a collaboration with Kubitschek.

Highlights: The museum, the church (it’s in restoration but I managed to get a peek at its famous mural), the open air restaurant, the Casa do Baile (Sanaa must have seen this one), the beach club, and the home he built for the Kubitscheks, which feels as if they might emerge at any moment, are once again vibrant examples of this giant of 20th century architecture who was able to think about intimate spaces as well as grand.

I practically wept at the haunting beauty of the twelve Aleijadinho soapstone prophets in Congonhas, and arrived in the colonial mining town of Ouro Preto. (You can still stay in an original Niemeyer duplex in the Grande Hotel with one of his signature winding staircases.). I happily lost myself in the cobbled streets of the colonial town and visited the three local museums—the Inconfidencia is an excellent intervention into a former slave prison. It wasn’t until I returned to the States that I learned that Ouro is another town also directly at risk from mine disaster as is much of Minas Gerais, once the wealthiest pocket of Brazil.

Arriving in Rio at the famed Santos Dumont airport was the first time I had a real chance to assess my vivid memories. The city is still so beautiful, where mountains meet the sea, but at every turn, the favelas remind of the societal disparities. (One even still bisects an extravagant private golf club.) Nevertheless, the display of modernist, art deco, and French inflected architecture is unparalleled and with the right guides one can access some hidden spaces that are an aficionado’s dream. I learned more about Lucio Costa and his Carioca school confederates Affonso Reidy, the Roberto Bros, Paolo Werneck, Jorge Moreira et al.

Highlights: We went to the roof of an adjacent building for a view of the famous Niemeyer-Burle Marx Ministry of Health which was at the top of my list (closed for restoration as so many projects are, alas), explored the hidden upper reaches of the Brazilian Press Association, the perfect reinstallation of the Burle Marx garden at the top of the (very private) IRB corporation Roberto Bros designed building.

The Instituto Salles was also partially closed for installation, but its outdoor spaces are elegant and well preserved in contrast to Oscar Niemeyer’s own house which, though technically in restoration by his family, is a mess. An expedition there with two intrepid architects who care deeply about its progress enabled me to see close up just how much is needed, and is not being done. Though I had written about the out of town Sitio Burle Marx, I was unprepared for its wild majesty and the many 17th century domestic structures left as Burle Marx inhabited them. The Sitio was apparently the scene of wild parties and gay life that garnered him quite a reputation at the time, but only enhanced the enchantment of this extraordinary space for me.

(Note well: There is a completely new oasis in the Leblon district, the Janeiro Hotel set to officially open in time for Carnival next month. This boutique heaven will certainly draw the smart set away from the famous Copacabana Palace. If you look left, you see the Corcovado. If you look right, you are facing Ipanema Beach. It has almost every service a larger hotel would have—and an especially engaging staff. At the end of a day of seeing many buildings in disrepair, it was particularly welcome. Anyone who is considering Rio—for example for the Architecture Congress in 2020—would do well to base herself here.)

In Rio, shorts is the uniform. In Sao Paolo people wear suits and build enormously high walled compounds. Brutalism reigns. (Again I was warned about crime, but experienced no qualms myself. One homeowner told me he had been held up at gunpoint in his shower and had left his absolutely primo brutalist Paolo Mendes da Rocha house in the care of his brother). Mendes da Rocha himself, now 90, is, however, apparently undaunted and still maintains his modestly located downtown office. Though busy , SP certainly has a less exotic, hothouse air than Rio.

Highlights: The projects of Lina Bo Bardi, the Italian architect who together with her husband Pietro commandeered the Brazilian art and culture world in the 1950’s and 60’s via the Museum of Sao Paolo, her stewardship of the museum and university in Salvador, their joint editorial supervision of their magazine Habitat, her truly egalitarian SESC Pompeia culture center and her own Casa De Vidro are still first class examples of civic and botanical engagement combined with architectural splendor (more soon on Bo Bardi). Proud homeowners welcomed me to their singular brutalist houses. Niemeyer’s grand Ibirapuera Park is vast and undergoing very slow renovation. Artigas and Cascaldi’s architecture faculty at the University is a majestic building but from my perspective, compromised by layers of apparently unrestricted grafitti. It’s in vastly better shape however than its counterpart architecture faculty in Rio.

Brazil has probably the greatest concentration of important 20th century architecture as anywhere in the world. Private funding for preservation is scarce, there seems to be precious little corporate support of these structures.

Mine was the only American I heard on this trip, and very little else. Argentinians were the few tourists I encountered. Many have been scared off, I imagine, by the onslaught of frightening front page news. The Brazilians are among the liveliest, most welcoming, citizens and their creative professionals among the most erudite. I urge Bolsonaro to reconsider his priorities. Brazil’s artistic heritage is one of its strongest suits and can only serve to deposit prized dollars into its coffers. I returned wanting to install ramps, winding staircases, philodendron. And a set of drums.

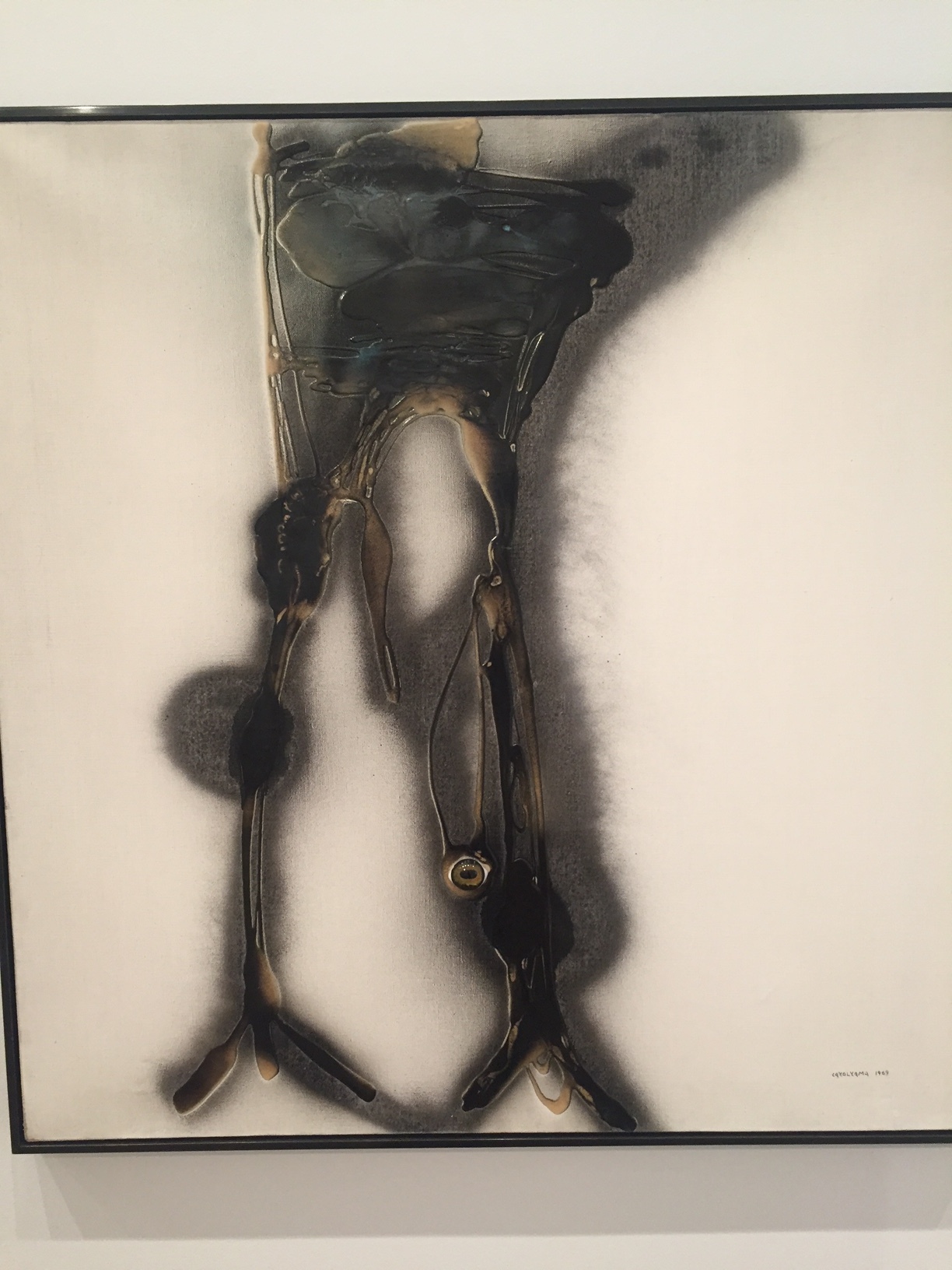

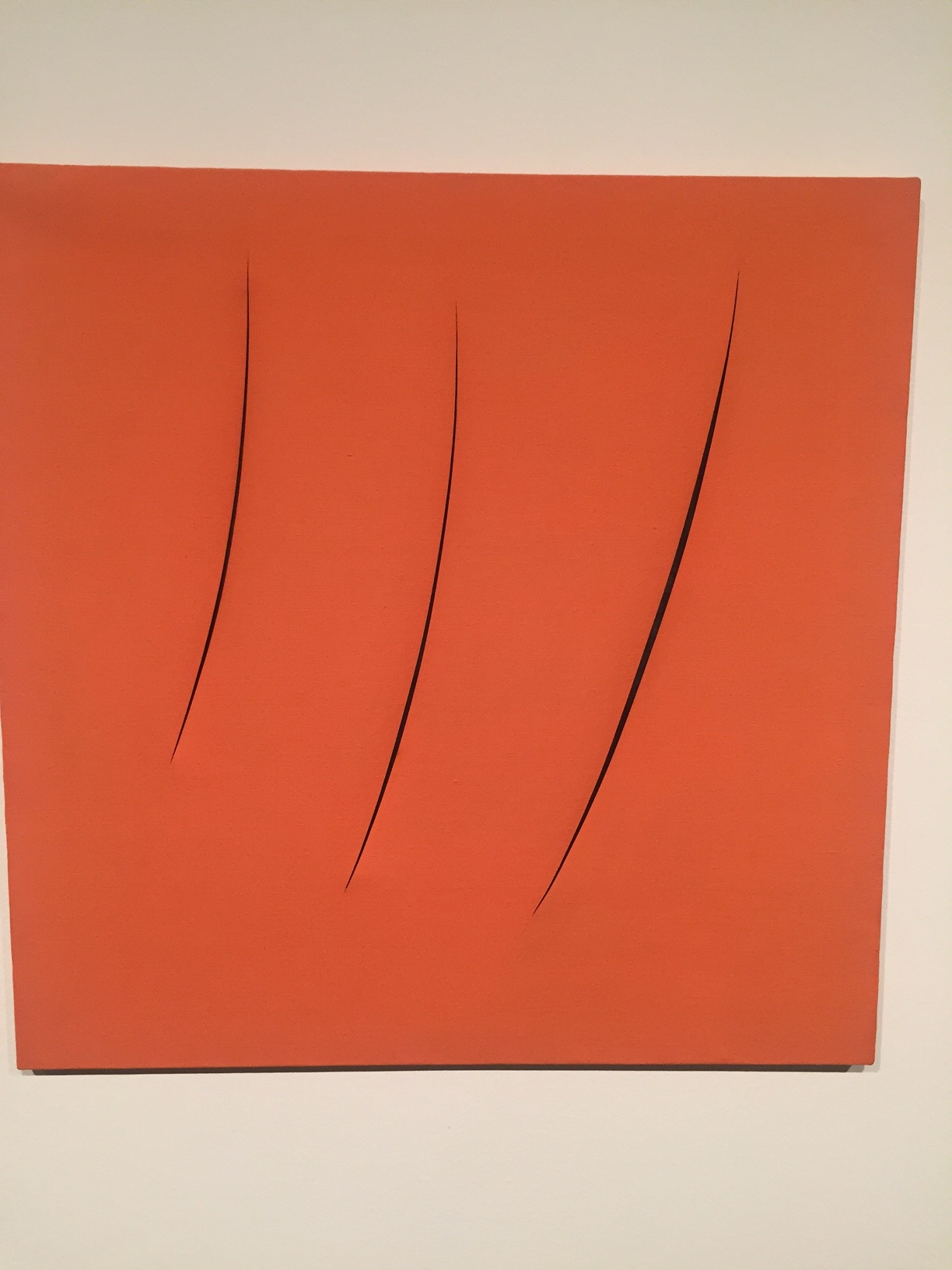

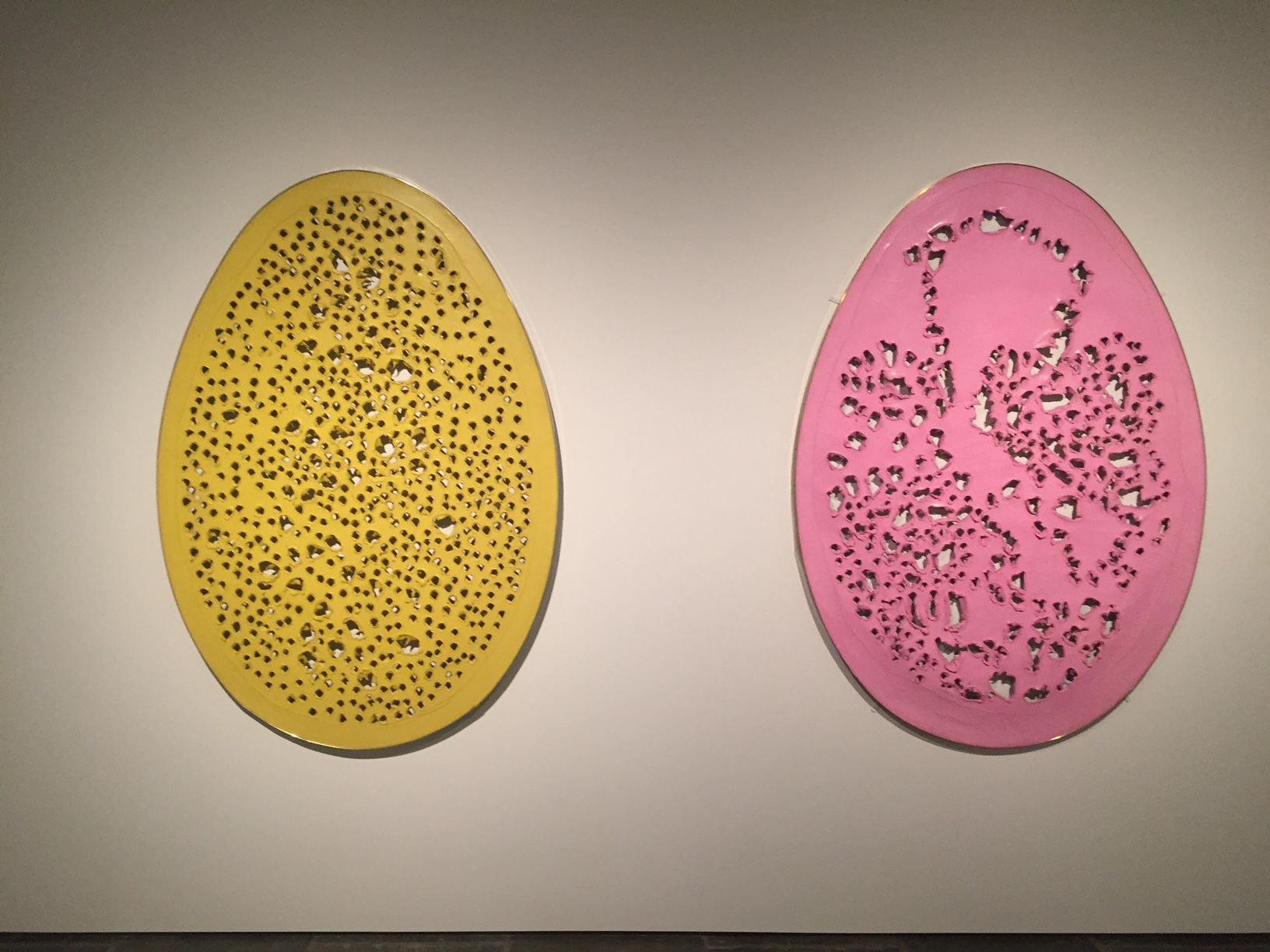

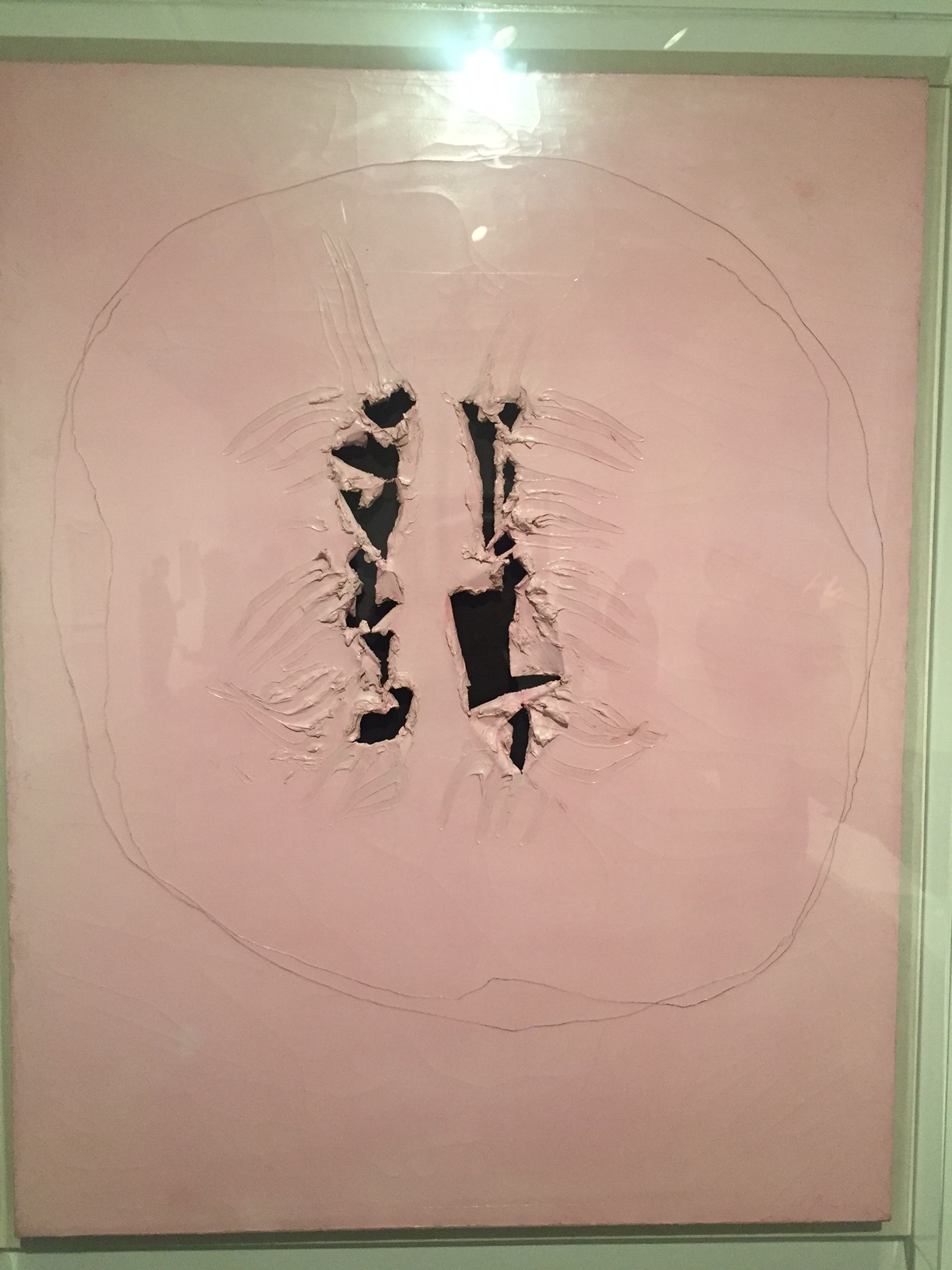

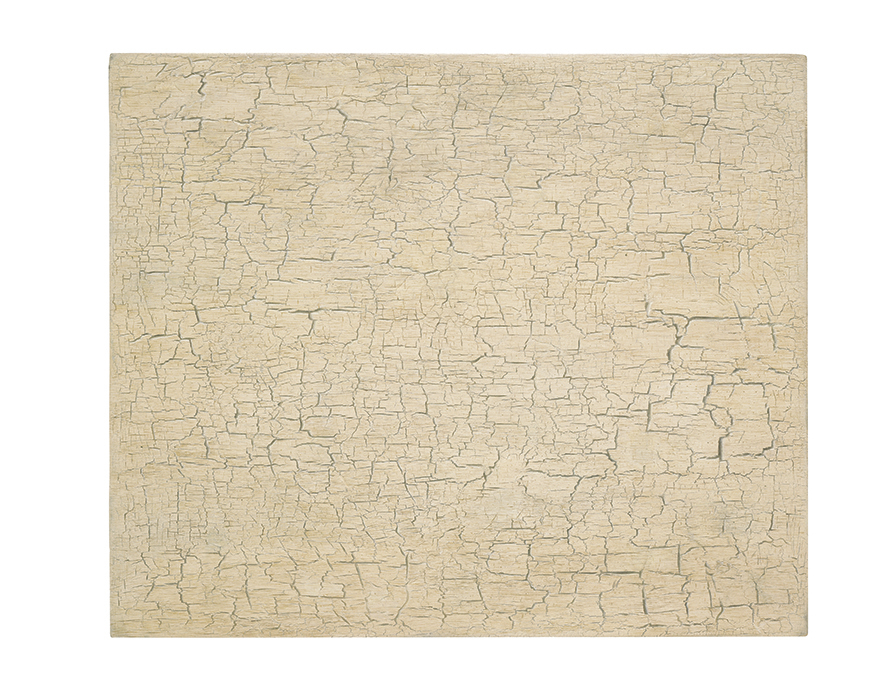

Lucio Fontana: On the Threshold at the Met Breuer

Lucio Fontana: On the Threshold at the Met Breuer comes at the proper moment. We are all ready to pierce and slash things right now, and Fontana gives us a vision of how we might do that and also produce beauty. What better metaphor for our times?

In his early years, Fontana, an Argentinian-Italian hybrid, made wonderful sculptures with a rare freedom both in form and color also riffing on the Majolica which was omnipresent (they oddly reminded me of Dana Schutz’s new series). His work was popular almost right away and he received a commission on the Life of the Sea, which showed his affinities for the natural world. They were to be totally obscured in the later work.

He is particularly famous for two series that broke through the picture plane.

The ‘Concetto spaziale,’ which were first conceived as screens for the transmission of light, display holes punched in patterns on canvas connecting us to the void, the infinite, the 4th dimension.

The early gallery of these, without chroma, but instead a kind of washed out beige, are so very pure.

I feel like my heart is being pierced. Somehow they made me think of Janis Joplin’s lyric “Take a little piece of my heart now baby.”

Later, he added chroma, glass and stone and the paintings grew larger, but those don’t have the same resonance. There is actually a pink painting that looks like the cavity of the chest—perhaps too literal.

His “Cuts” series was considered his most radical, acts of sabotage painting. These are likely the ones you are more familiar with. Fontana said it was as hard to decide where to put the cuts as anything else he had done, and that he then folded them back and affixed them to the back of the canvas. No more fenestration as with the holes—just violent fissures. Once again, it’s impossible not to think of our contemporary social and political anguish.

A decade later, he had cycled through color and come back to white, using house paint because it was flatter.

Fontana has come back into vogue along with his compatriots Alberto Burri and Piero Dorazio and the mid-century school of Italian painting, design and architecture. Here at the Met we have the reason why.

January 23 - April 14, 2019.

Dana Schutz at Petzel Gallery: Imagine Me and You

Dana Schutz’s new show at Petzel opens on a woman painting in an earthquake. Her sneakered foot rests on a skull.

I think of Schutz having to work after the earthquake of the last Whitney Biennial, debris flying at her that she never expected, yet managing in spite of the --in my opinion--wholly undeserved misplaced vitriol about her painting of Emmett Till, to carry on with her work and her life.

Another painting in this collection shows a woman on a treadmill watching a blank screen. Maybe this was the only way to exorcise that troubling time.

We are told as readers never to conflate the work with the writer. And yet it’s impossible not to conjure up the life surrounding this new work, at odds with a self-effacing, private self. Instead it is filled with monsters and demons, bold slashes of color, trouble, wandering, marching and strangers as well as the occasional more pastoral: the sun, a boatman, a mountain group.

My favorite image, having spent the previous evening with Manet’s Odalisque is Schutz’s equally provocative version, a green eyed woman who boldly confronts the viewer, refusing to sink beneath the waves, a pelican with a raspberry standing in for Laure and her bouquet of flowers.

Shutz imparts more emotion into a finger or a limb than most artists can into a face. Each element of a body is articulated. It reminds me of flamenco dancing—sometimes your head is going one way, your hands another, your body yet another. Your feet are stamping to get attention. Yet somehow the whole makes sense if you add enough emotion. Emotion is the overlay to Schutz’s more formally excellent qualities. I feel a gut punch at every image.

There is still plenty of Philip Guston in Schutz and even Picasso, but that’s all to the good. Schutz is not afraid to reference her heroes and heroines, to give credit where it’s due. Her bronze sculpture is new and engaging, her painting impasto translating readily into the dynamic, often humorous creatures as if Giacometti had run riot.

I am obviously a fan of Schutz’s bold and ambitious work. I believe she is one of our leading, most authentic artists.

Dana Schutz, Imagine Me and You, Petzel Gallery, 18th Street, open until February 23.

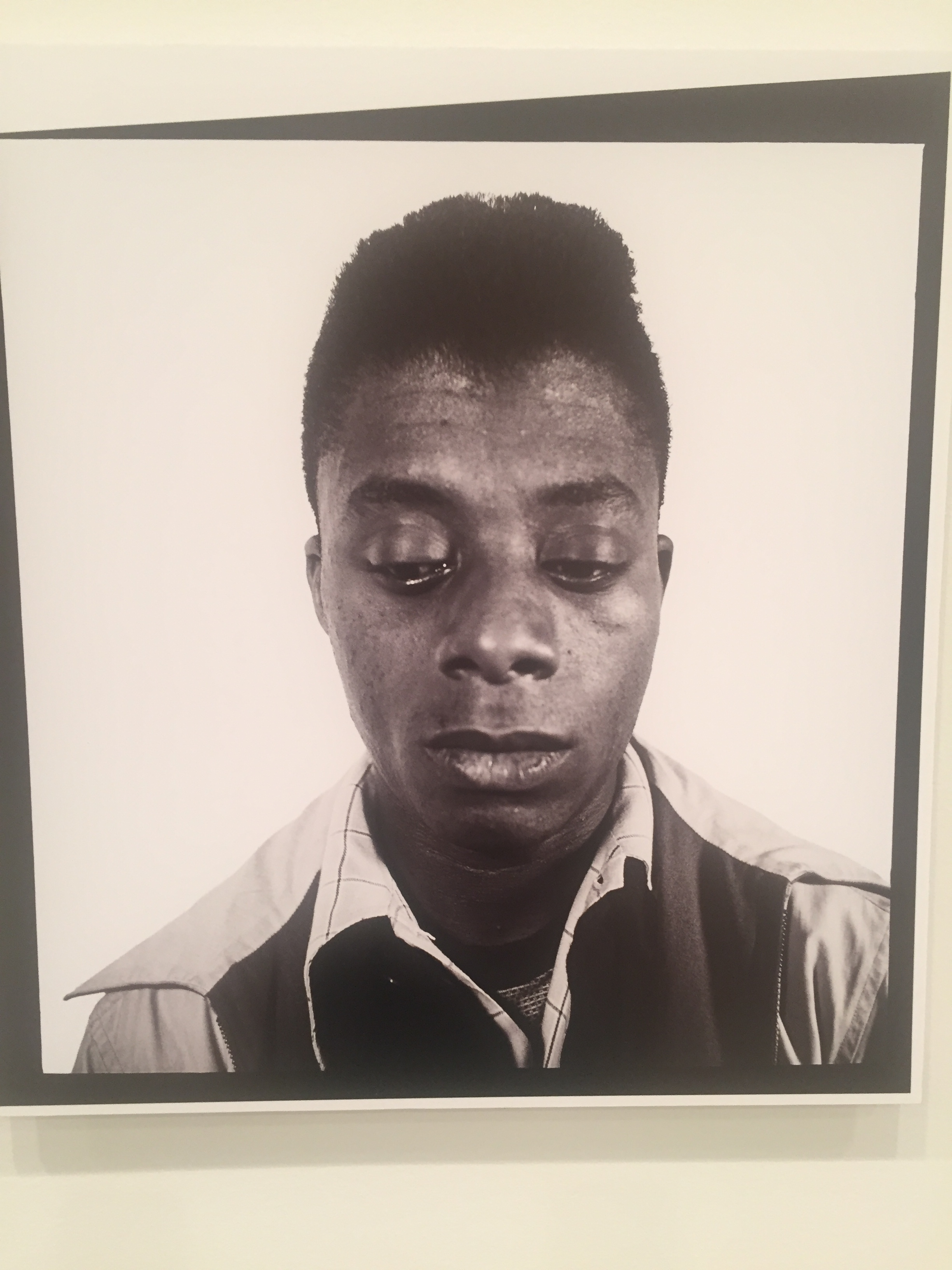

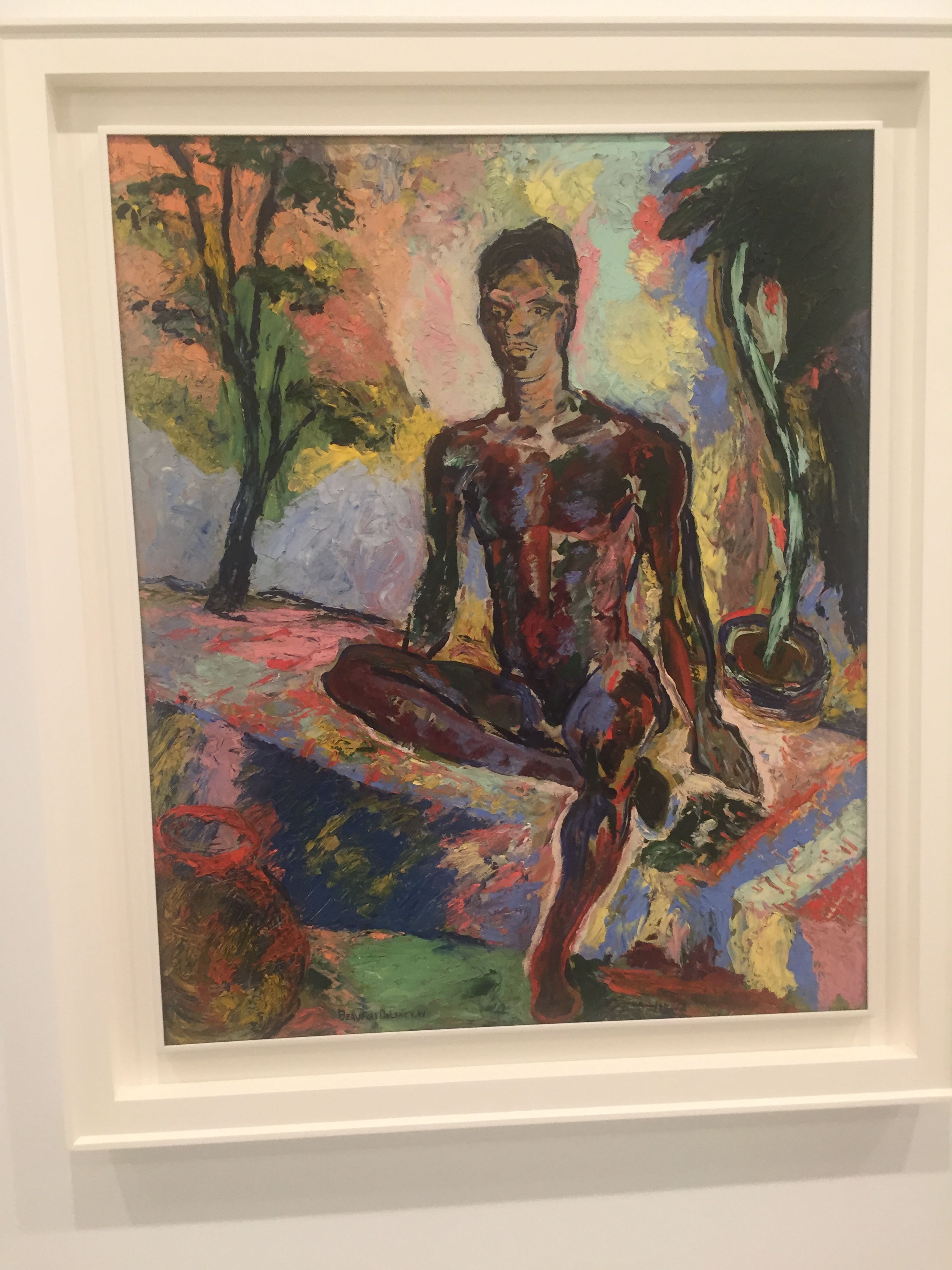

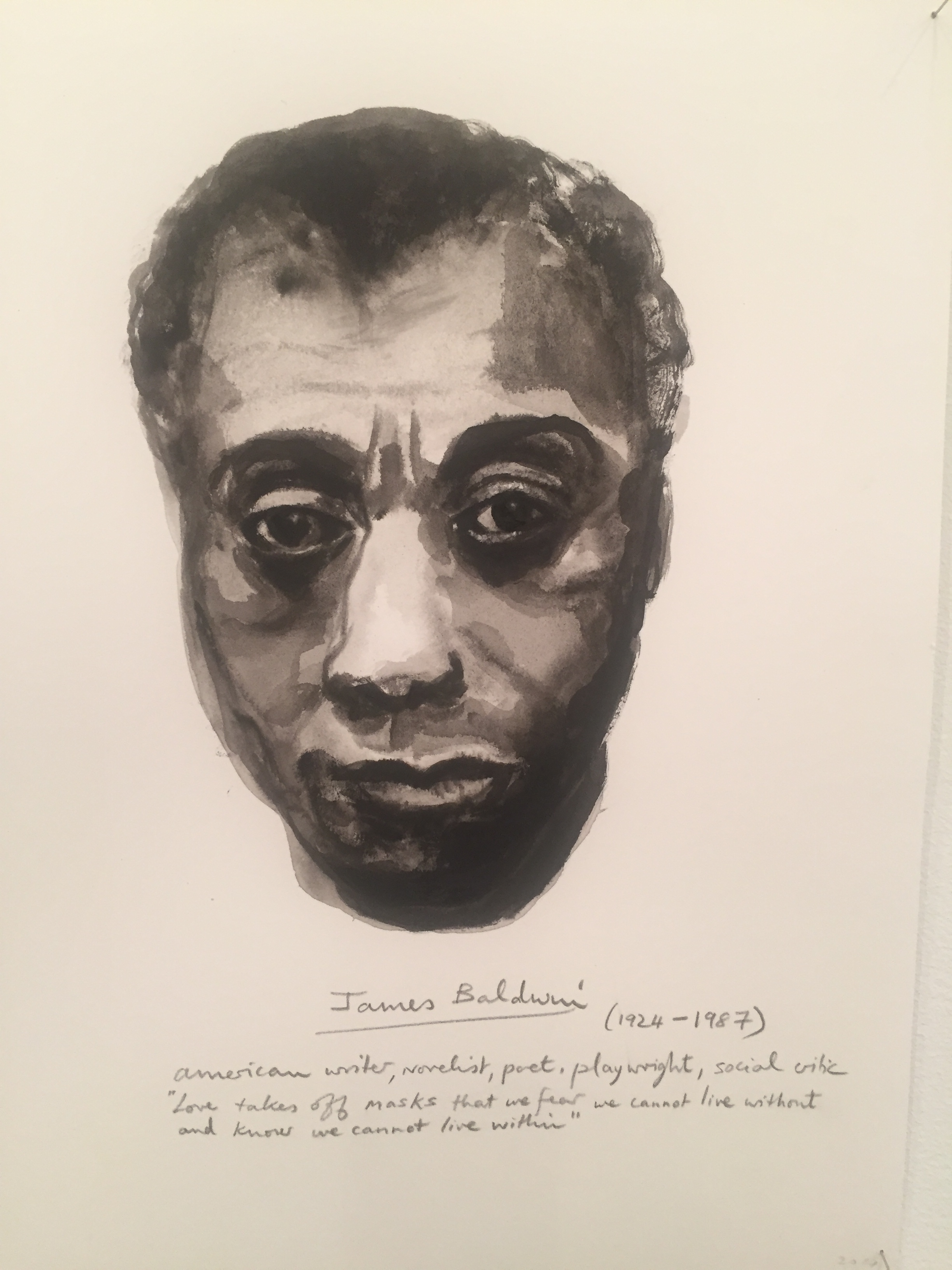

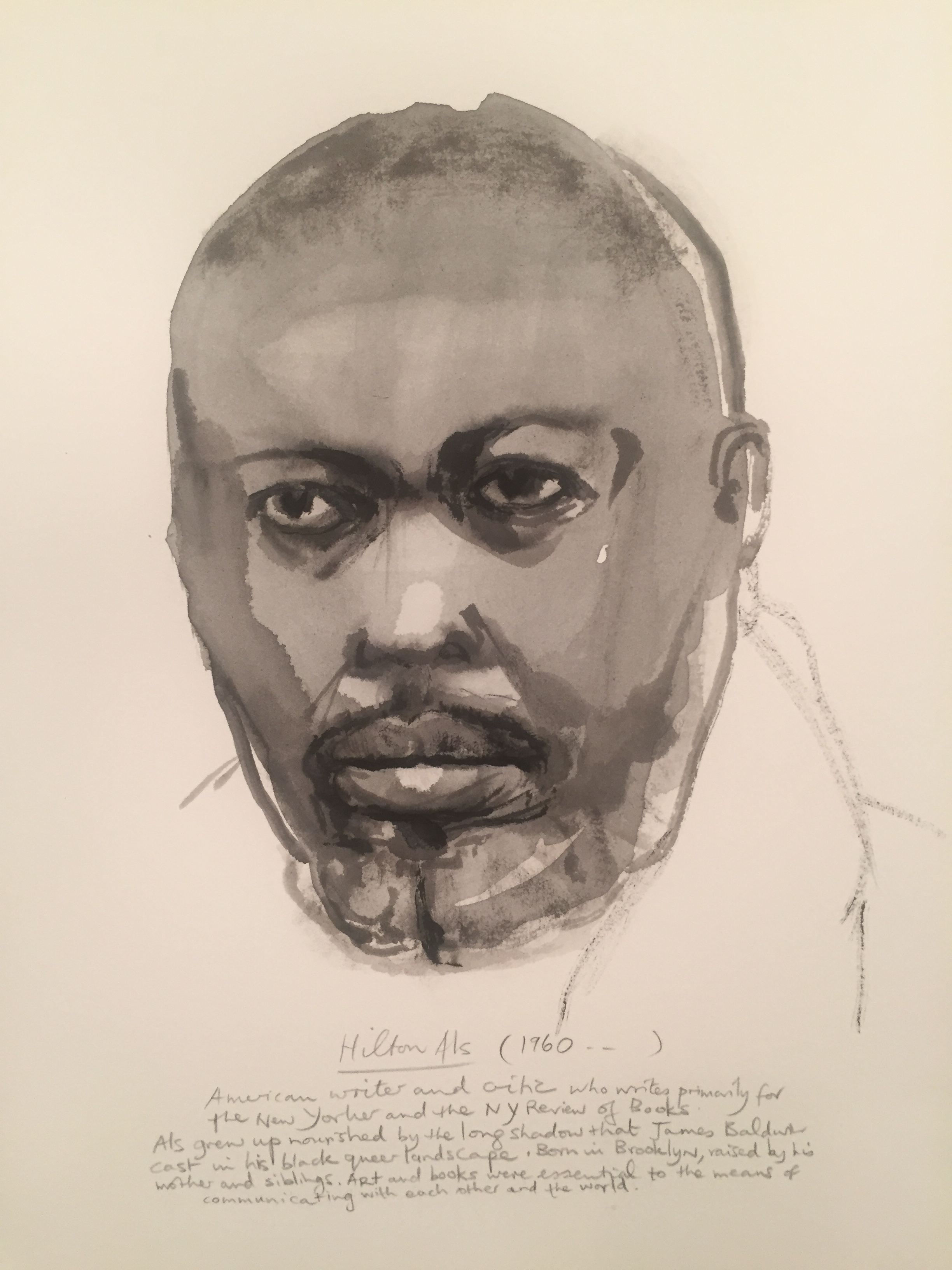

God Made My Face: James Baldwin via Hilton Als at David Zwirner

“I remembered myself as a very small boy, already so bitter about the pledge of allegiance I could scarcely bring myself to say it…I was in short, but one generation removed from the south.”

So opens the moving exhibition on James Baldwin, God Made My Face, curated by Hilton Als at David Zwirner. In two distinct sections, A Walker in the City and Colonialism, Als offers us original text and images as well as commentary by fellow artists.

“He will not be swiftly forgiven for having turned so many tables,” Baldwin writes of Michael Jackson. The same could have applied to Baldwin himself.

Baldwin had a fraught childhood: his mother fled from his real father and traveled north. His stepfather, a preacher, had 8 children with his mother and especially disfavored Baldwin. After trying to be comfortable in his own skin in Harlem, he escaped to Paris. As for so many of us, Paris was both the tonic and the siren we thought would let us be who we really were. You didn’t have to be black and homosexual to want to have the artistic freedom of Paris. His friends became his family.

Baldwin had a slow but steady emergence from his painful chrysalis as a profound writer (original editions of the books are on display ). But he also kept a close eye on other forms of culture: film, theater, music, photography. His friendship with Richard Avedon began at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx (my father also attended) and they stayed close.

He was especially keen on filmmaking, but that did not work out as well as he had hoped. His métier instead was to dissect himself, his culture, the people and circumstances who had discouraged and pigeonholed him including his own family.

After publication of The Fire Next Timein 1963, Baldwin emerged as a leading cultural figure, one with agency. He then had more courage to take on battles larger than his own personal demons, ones that had long preoccupied him: the complicated legacy of civil rights, colonialism and its aftermath, miscengenation.

The topic of homosexuality was more challenging. Here at Zwirner, Glenn Ligon and John Edmonds weigh in on his behalf. Kara Walker, represented by her graphic film 8 Possible Beginnings,has never been abashed about telling it like it is. Marlene Dumas’s black and white watercolor series of writers and artists she periodically adds to imports a very personal dimension to some of Baldwin’s friends and contemporaries.

Curator Hilton Als himself seems to have picked up where Baldwin left off. Both as an excellent excavator of historical black culture (his last exhibition on Alice Neel also at Zwirner, was one of my favorites) and a supporter of contemporary black culture he excels. Yet he is a fluent about white culture as anyone.

With the film If Beale Street Could Talk and this exhibition, Baldwin re enters the culture for another generation.

Posing Modernity at Columbia University's new Wallach Gallery

Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet to Matisse to Today has a long title but in this case its thoroughness mirrors the truly deep and expansive exhibition at the Wallach Art Gallery at the newish Renzo Piano designed Lenfest Center at Columbia University. Based on her disseration, Denise Murrell has curated an investigation of gender, race and class via the role of black female model in 19-21st century art history.

It’s the precisely right exhibition at the right time at the right place.

Sponsored by the Ford Foundation, the exhibition takes as its premise the centrality of the black female figure in modern art, that these models were both much more important to the development of painting and to the personal lives of their painters than anyone has presumed. No longer exotic, they were full participants in the culture. They became individuals instead of stereotypes.

There are so many surprises in the exhibition that my companion and I, an erudite former curator and head of a foundation found ourselves constantly stopping and pointing things out to each other.

Who knew that Alexandre Dumas pere was black?

Who knew that Matisse regularly visited Harlem?

Who knew that La Dame aux Camelias and subsequent adaptation La Traviata was based on the story of a mixed race American actress called Adah Mencken who had been one of Dumas’s many mistresses?

Who knew it was Baudelaire’s visits with actress Jeanne Duval and his sessions with Laure, both Civil War era free black Parisians that inspired Manet’s Olympia and other paintings?

Olympia is alas not here but you can always find her luscious white body, her black cat and Laure as her maid carrying flowers at the Musee d’Orsay where this exhibition is next destined. We are sorry to miss her in the flesh, since so much of the exhibition derives from this historic painting but instead we have a variety of prostitutes, nannies, slaves from the West Indies, circus stars and grisettes from Paris in images from Nadar, Degas, Norman Lewis, James Porter, James van Der Zee among others. it is another kind of bouquet.

The show summons how extensive the pattern of black modeling was for 160 years, how close some of the models were to these famous painters, and how much their work was influenced by the then novel inclusion of their race and gender in works no longer destined for the salon. The legacy of Olympia runs deep and long. The last room is devoted to contemporary riffs on the Manet from Ellen Gallagher to Mickalene Thomas.

For me, even as a writer not a painter, the painting has cast a long shadow, summoning the 19th century literary heroines who were both revered and sometimes destroyed by their desire and devil-may-care. Behind these paintings were some very brutal stories of painterly and writerly disaffection and dismissal. Yet in the end, these models have more than withstood the test of time and represent an uplift of subject and grace.

Columbia’s new complex of buildings by Piano is a fine home for the show and rightly sited in Harlem and it bodes well for the university as a legitimate and first tier venue for class A material. Congratulations to all.

Baudelaire

Manet

P S. I include two images of Manet and Baudelaire not only to show you how lively and modern they look but also to see that it’s possible that Baudelaire was separated from Bill Murray at birth!

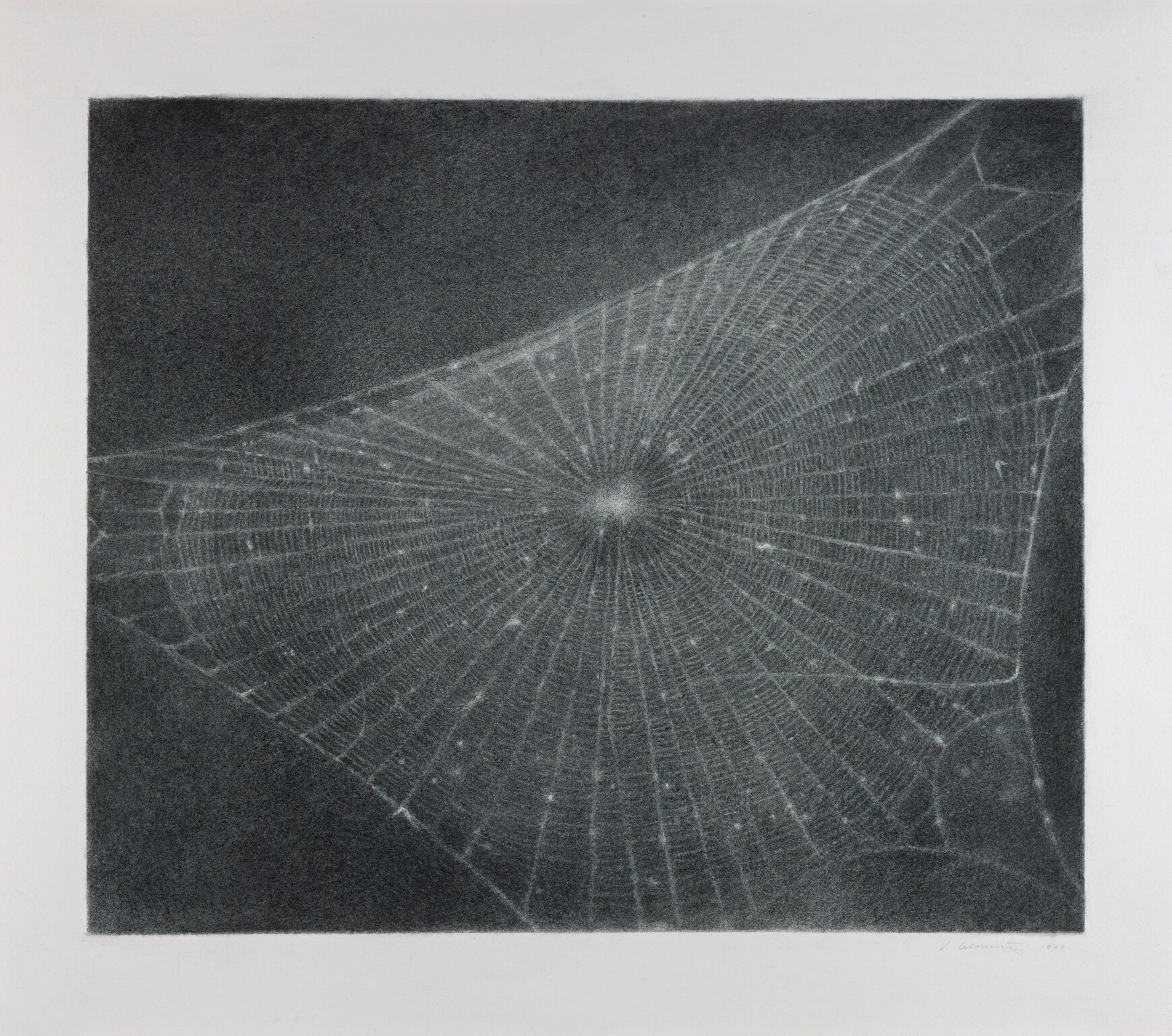

Vija Celmens at SFMOMA: To Fix the Image in Memory

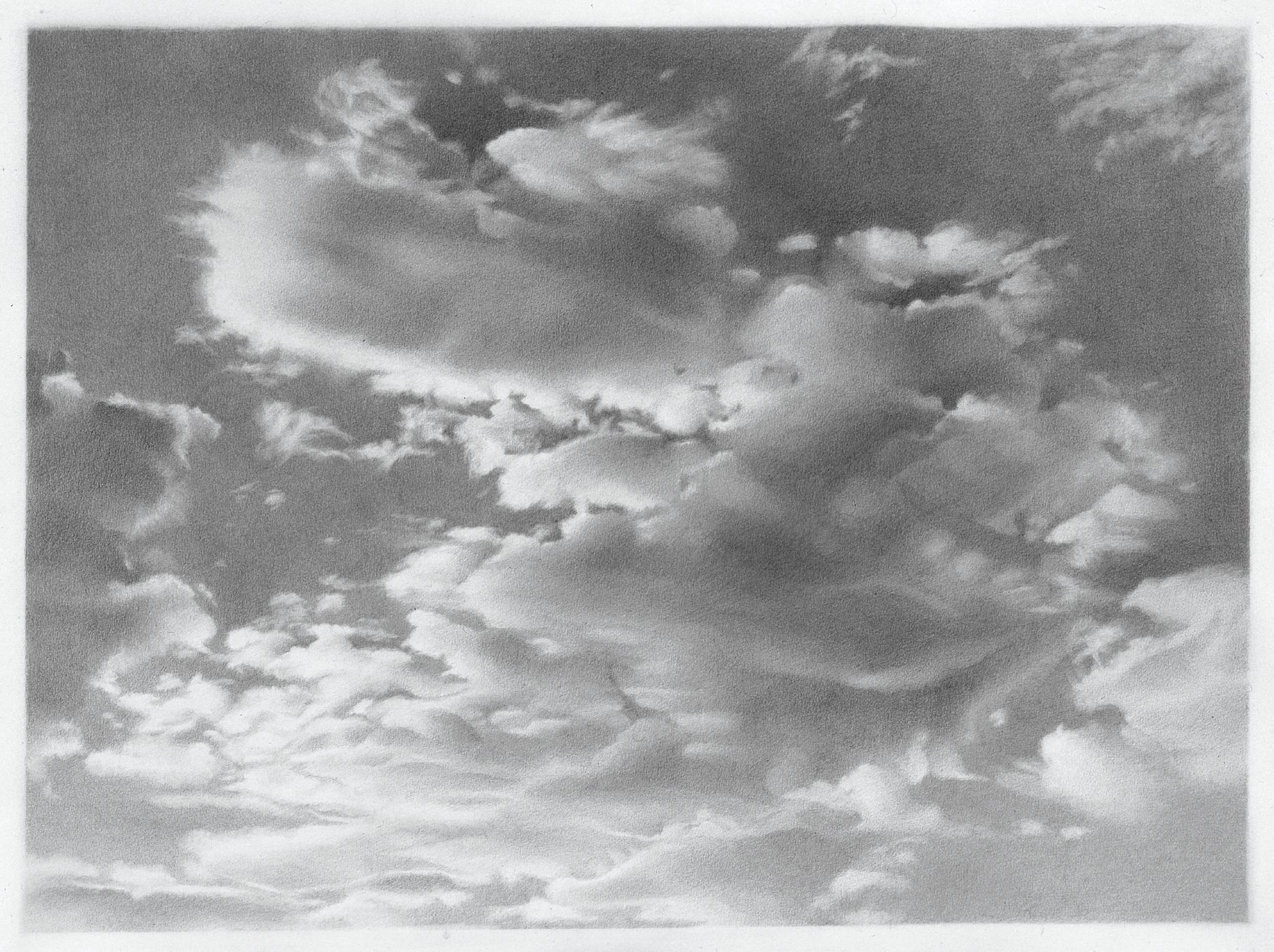

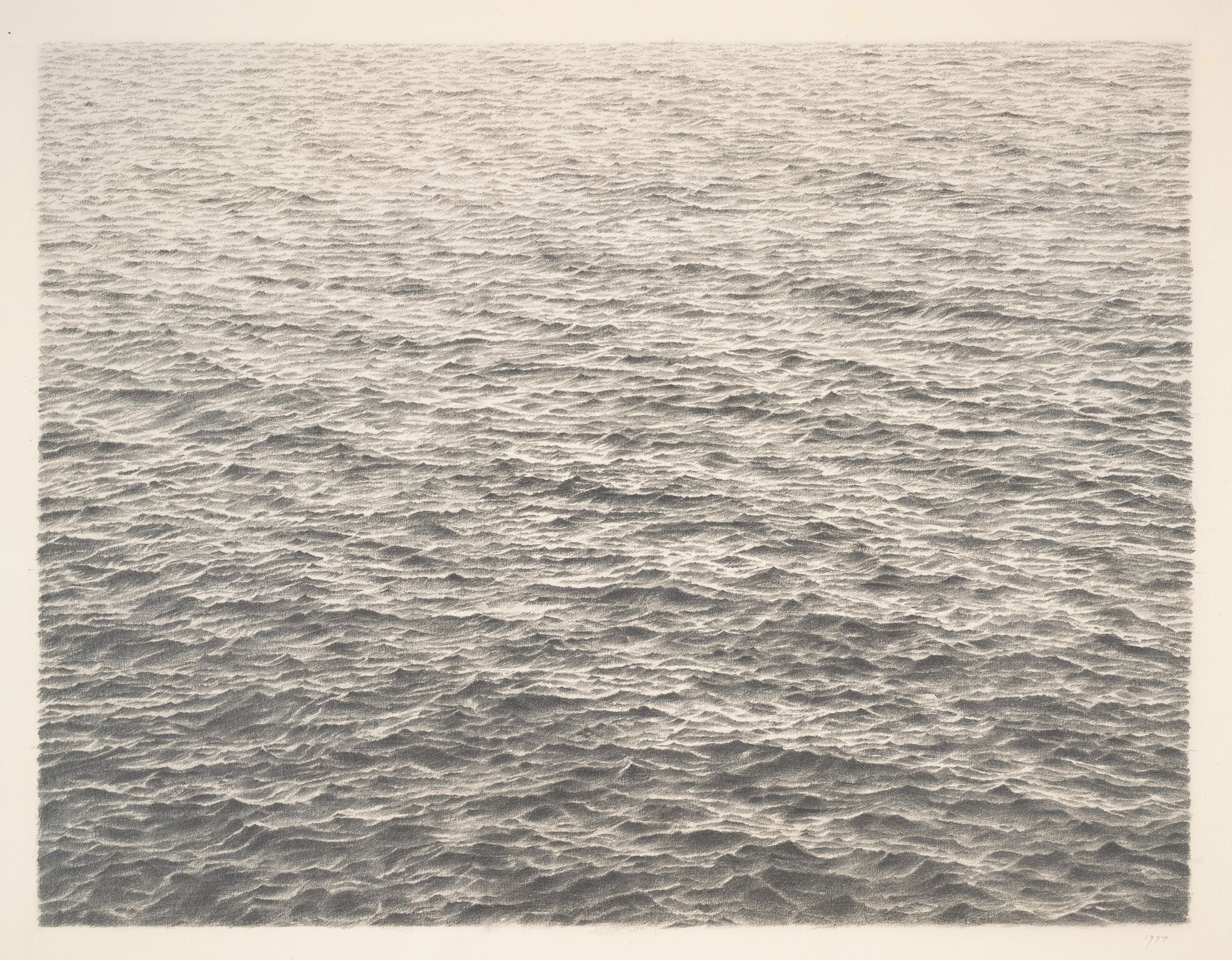

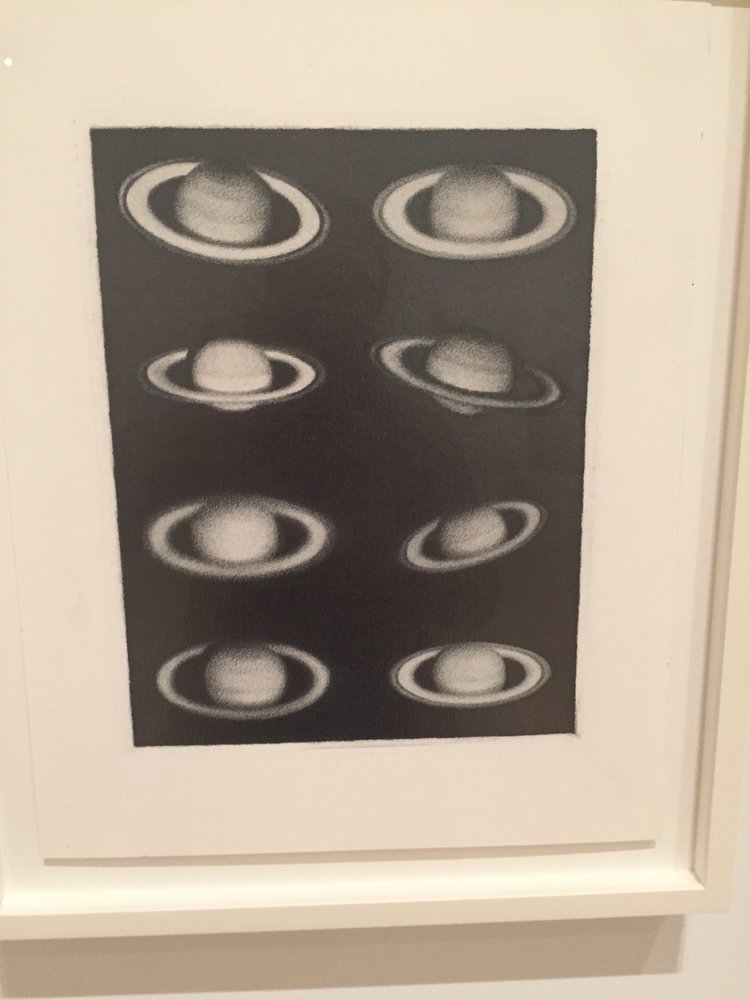

The Vija Celmins exhbition curated by Gary Garrels at SF MoMA is very beautiful. Quiet, reflective, deep, it gives one the perfect January pause, a diet for the mind and spirit. Though born in Europe, California gave Celmins, who attended UCLA, some of her greatest subjects: ocean, sky and desert. Her rendering of a craggy, desert landscape with its rusticated ochre reminded me of the crags in the Burri Cretto in Sicily.

In her meticulous graphic renderings of ocean waves, stars, planets, spider webs and other natural objects, she worked lower right to upper left on a bridge to avoid smudging. She never erased! How wonderful it would be if we could all be so precise in our lives. Her early work in the sixties, both Magritte-an and Oldenburg-ean was a surprise to me, but showed a sense of humor that doesn’t necessarily appear in the mature work. She called this body of work “falling out of the picture plane”. A view of the LA freeway from inside a car is just about as close to Joan Didion as one could get in imagery, Tuesday Weld notwithstanding.

In paring her later art back to its essence, Celmins is not intending to be spiritual but rather locate the meaning in physicality of the natural things she studies so carefully according to Garrels. Celmins approaches her subjects the way writers often approach their work. Is it real, or is it my memory of it that is real? Memory imposes an extra layer. In Celmins case, it is all to our benefit.

Be sure to take a look at the videos on the SF MoMA website. Celmins, who now lives in NY, will be at SF MoMA for a talk on January 31.

The Head and the Load: William Kentridge pulls focus on Africa and WW I

William Kentridge is a polymath, an entrepreneur, a ringmaster, an historian, a singer, a writer, a visual artist, a designer, and so on. There is probably no challenge too great for this maestro of the visual and performing arts.

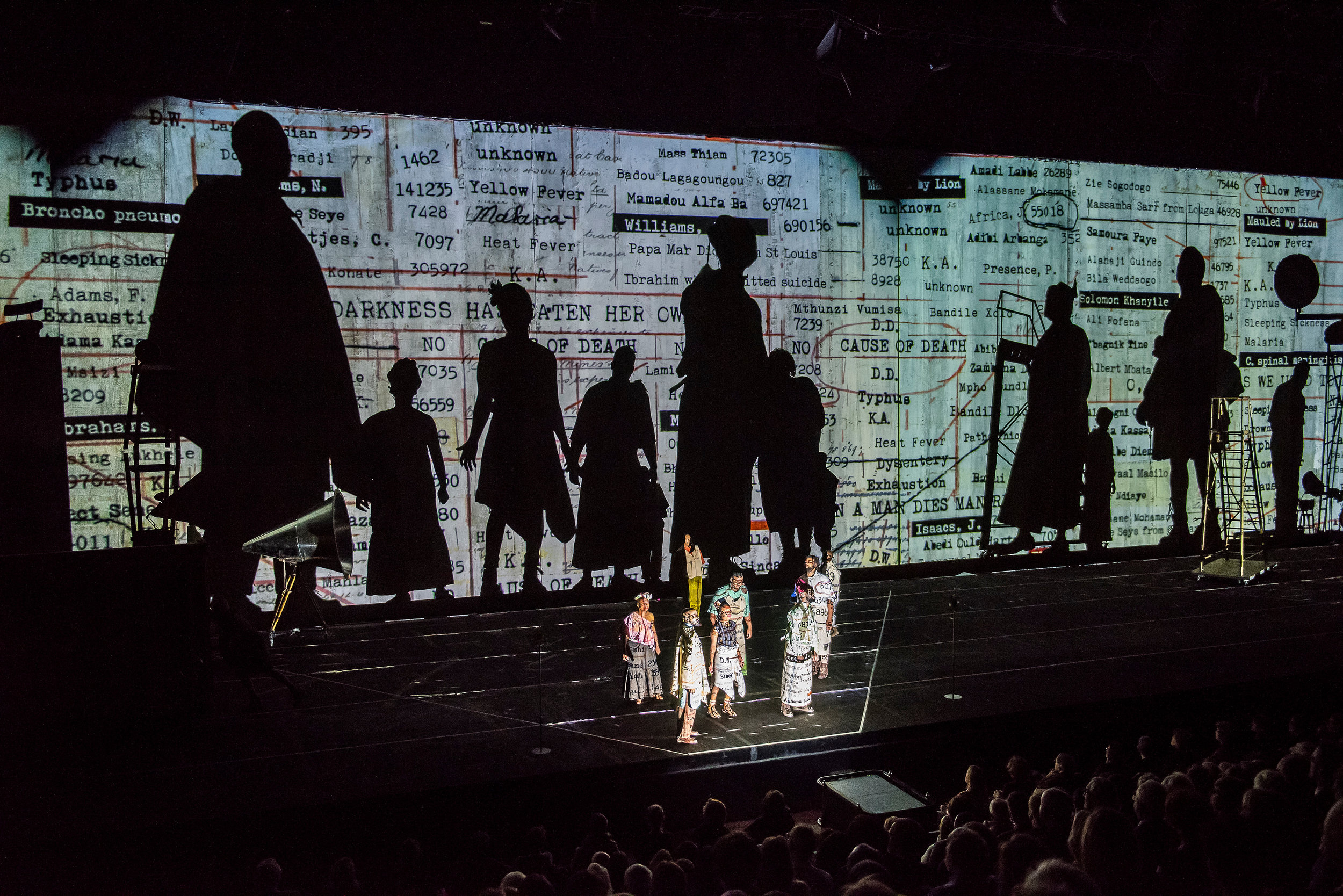

The Head and the Load, a production workshopped at his The Center for the Less Good Idea atelier in Johannesburg and at Mass MoCA, and performed already at the Tate and in Germany, arrives at the Drill Hall of the Park Avenue Armory already finely tuned. I’ve long had trouble with seeing productions try to successfully fill this vast space. But apparently if you build it they will come—and there is no one better than Kentridge to think big.

Taking as his ostensible subject the role of Africans in WW 1, Kentridge envisions a world where Africans are finally allowed to speak truth to power about what it was like to be a human vehicle (soldiers and porters) for troop strength and munitions during this global war in which Africa became part of the spoils. With his principal collaborators, composers Philip Miller and Thuthuka Sibisi, choreographer Gregory Maqoma, a local NY chamber orchestra The Knights and other accomplished dancers, singers, musicians and actors, Kentridge deploys some of his signature elements: live and video shadowplay, original documentation, animation, processionals et al) and delivers a vast and moving panoply of heartbreak and political strife.

In an artists talk before the performance, Kentridge described the gestation of the piece in an 8 day workshop in Joburg with 60 artists that gradually evolved over the course of other subsequent workshops. Some elements were also stimulated by his processional piece in Rome on the Tiber River. For The Head and the Load, Kentridge modified this processional approach with waystations: breaks for us to understand the deeper history and meanings of the conscription of native African troops into a far away war they barely understood.

English, French, German and African languages are deployed alongside voices in an arsenal of sounds that both emulate aspects of the destruction and elevate it. Having seen Kentridge perform the Schwitters Ursonate last year I heard the elements of Rakka Ta Bee Bee in the opening moments. Instruments are voices, voices are instruments, and as Kentridge says, he would be hard pressed to find opera singers who would challenge their vocal equipment quite so audaciously as these performers are willing to do.

Kentridge is recalling Dada and its emphasis on collage, on the spoken automatic word, on repetition as a tool for engagement. But the most affecting moment for me was the extraordinary pas de deux between two soldiers, one in a state of collapse, the other trying to haul him up and get him to salute. This is probably the most affecting new piece of choreography I have seen in a very long time, and is as moving and intricately plotted as any of the Swan Queen with her Prince. Kentridge says he wanted to emphasize the contrasting “tenderness and violence”

Kentridge resisted the temptation to focus on one character’s three act journey, a more conventional operatic approach. Instead this collage method (his default) allows him to graze on many stories which percolate, evaporate and then re-constitute as the evening progresses.

I still have trouble with the Drill Hall. My head moves in a kind of robotic 180 degree rotation, trying to capture the fullness of what the team is showing me. It’s not only tiring, I think it distracts from the pithiness, the anguish, the intensity.

But ok. Here’s a guy for whom the work size is irrelevant. He can work small (Ursonate) or large (The Nose), in museums, or in performing arts venues with equal aplomb. He is bravely opening a different window on non-western culture and history for all of us and is to be commended.

The Head and the Load continues at the Park Avenue Armory through December 15.