Though I had seen many images from the Alice Neel show at the Met, I was not prepared for the breadth and depth of the actual exhibition. Fair warning: even with a ticket, in mid week, in the morning, the line was at least 30-45 minutes to enter. It is beyond worth it.

The exhibition provokes questions about her biography. If you go to aliceneel.com, you will be able to see marvelous photographs of her and her world and also learn the more granular details.

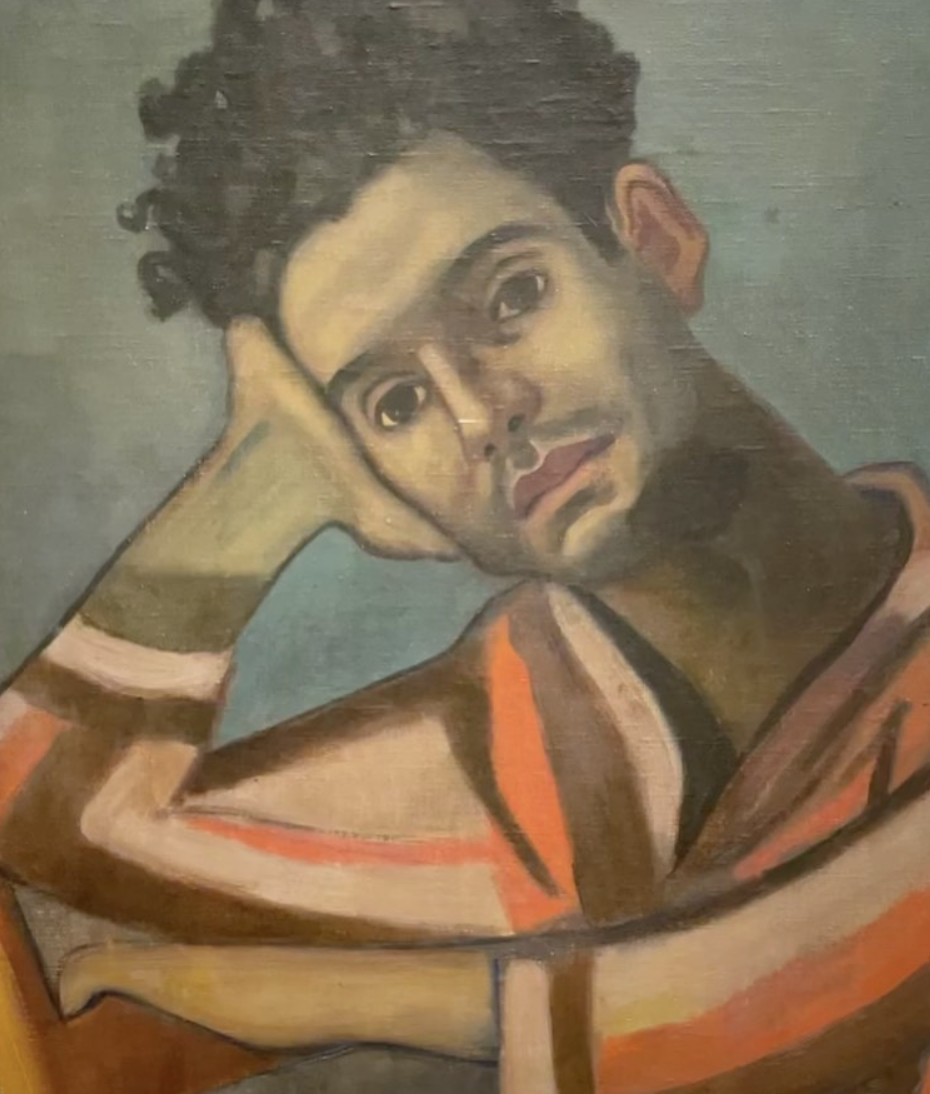

Though we are often warned not to conflate the life and the work, with Neel, it's impossible not to be struck by the number of marriages she tore apart, and the number of relationships of her own that seemed fungible. Neel felt free to pursue her passions, be they artistic or romantic. Some blew up on her. Her relationship with Carlos Enriquez ended in abandonment along with the death of one daughter and the hijacking of another and her subsequent hospitalization for a nervous breakdown. Hot tempered seaman Kenneth Doolittle burned and destroyed a large archive of her art. John Rothschild left his wife for her, but she did not commit to him. Perhaps he reminded her too much of her more conventional Pennsylvania background. Jose Negron, a salsa band leader, pictured here in 1936, left his wife for Neel but interestingly, she ended up using her as a subject.

Not long after they got together, they moved to Spanish Harlem and she began the prolific, clear eyed rendering of her friends and neighbors that is such an important part of the exhibition. They had a child, Richard, together (originally called Neel!) but Negron moved on a few years later to another woman.

The libertinage of the age went along with the politics, and the artistic milieu. Inevitably, there was collateral damage. But at the Met, we see the affection she once bore for her lovers in her indelible portraits. West coasters take heart: the show comes to the deYoung in 2022.

Jose1936, Estate of Alice Neel

A playful Surrealist Lobster Hat at the Met Costume Institute

This hat, cherry red in the spirit of the season# and part of the Sandy Schreier collection now on view at the Costume Institute at the Met, was made by Benjamin Green-Field and his sister Bessie for their eponymous hat company Bes-Ben in 1941 (one way perhaps of avoiding prewar anti-Semitism was to add the hyphen?) Known as “the mad hatter of Chicago, it cannot escape notice that his lobster—y confection of surreal playfulness was in the spirit of Dali’s Lobster telephone now on view at MoMA.

Michelangelo stays at the Met

For the few years I worked at the Services Culturels housed in the former Payne Whitney mansion across from the Metropolitan Museum on Fifth, we used this rather nondescript statue as a coat or hat rack, ashtray, or place to wad a used cocktail napkin. When it was discovered to be a vrai Michelange I was rather nonplussed. My office which was vaguely like a bordello with a white shag rug and dark walls in a remade attic space was only one of many odd nooks in the building which Miss Helen Whitney had done up when upper Fifth was the boonies. Still the statue conferred a sense of decorum and history during a time of my life dearly lacking in same.