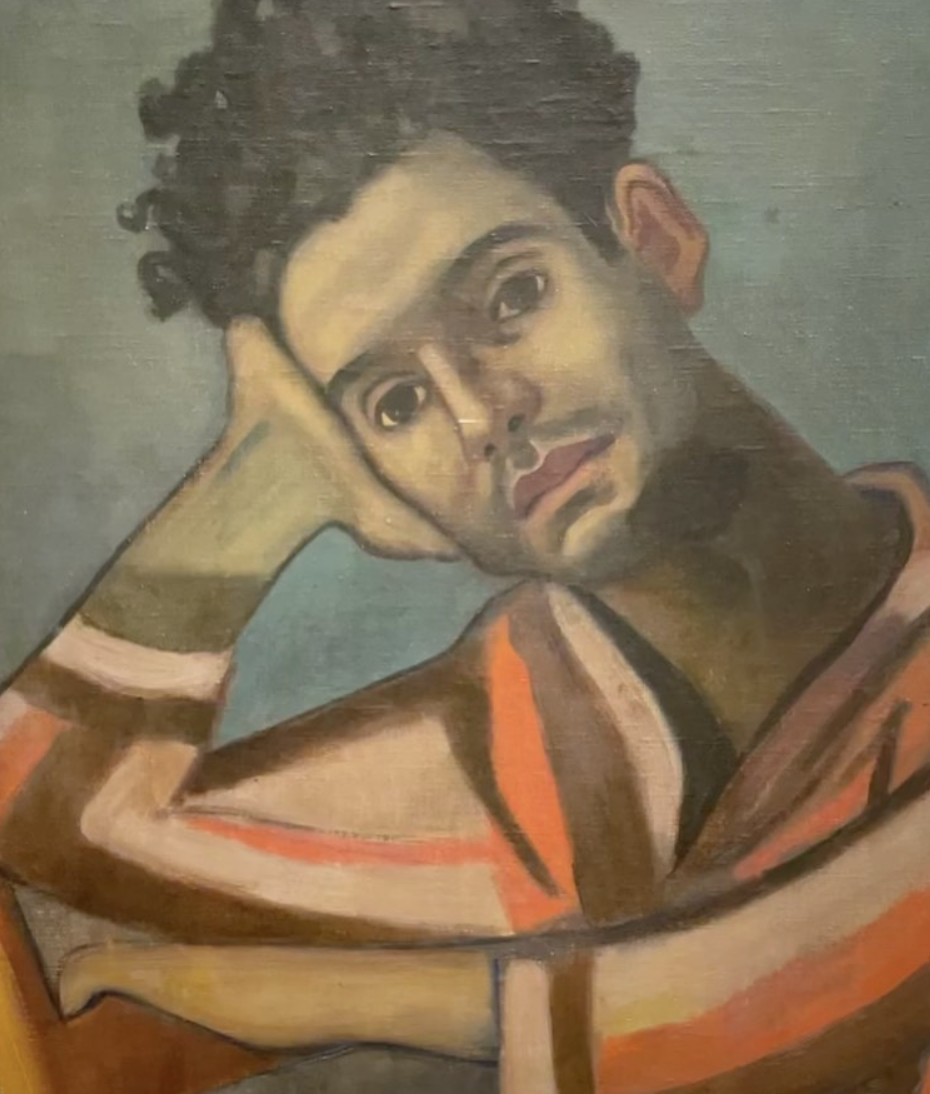

This painting by Wilfredo Lam from 1947, Tropic, came at a time when Lam, an outlier among the last group of Surrealists as an emigre from Cuba, had returned to his homeland and the region and had newly become engaged with the traditions of Afro-Cuban divinities and spirituality.

Lam had gone to Paris in 1938 after living in Spain and fought in the Spanish Civil War and been taken up by Picasso by whom he was much influenced and who helped him get his first show. He was also the Surrealist who made primitive and ethnic sources central to his art. You can still see the influence of Picasso in this painting in the new Modern hang at Lacma but there is also a whiff of voodoo and masks. Lam was itinerant and much married, shuttling around Europe and the Carribbean during the war years literally, on the lam from the Nazis.

When I finally got to see the beautiful small Centro Wilfredo Lam devoted to his work in Havana however, it all came together for me. It’s so sad to hear about what is happening to Cuban artists today.

A Painting Ahead of Its Time

If you had to guess, I am sure you would not say that this painting was made in 1932 because it is so contemporary in its bold colors and design. The artist is not that well known in the US. He is Flavio de Carvalho, a Brazilian polymath disrupter who was also an architect, a writer, an early proponent of performance and conceptual art and transgender culture.

His moment could be right now. Although he represented Brazil at the 1950 Venice Biennale, he did not get many projects built. But walls were not his thing in any event. He pursued the connections between art, architecture, literature and religion and fashion, once parading in downtown Sao Paulo in a puff skirt and blouse, towering over the crowd. Resolute, like Lina Bo Bardi, about the indigenous cultures of Brazil and Latin America, he incorporated their motifs into his designs and made cross culture and well as cross gender an ongoing theme.

The Definitive Ascension of Christ, 1932, Pinacoteca de Sao Paulo

The Inside World of Alice Neel

Though I had seen many images from the Alice Neel show at the Met, I was not prepared for the breadth and depth of the actual exhibition. Fair warning: even with a ticket, in mid week, in the morning, the line was at least 30-45 minutes to enter. It is beyond worth it.

The exhibition provokes questions about her biography. If you go to aliceneel.com, you will be able to see marvelous photographs of her and her world and also learn the more granular details.

Though we are often warned not to conflate the life and the work, with Neel, it's impossible not to be struck by the number of marriages she tore apart, and the number of relationships of her own that seemed fungible. Neel felt free to pursue her passions, be they artistic or romantic. Some blew up on her. Her relationship with Carlos Enriquez ended in abandonment along with the death of one daughter and the hijacking of another and her subsequent hospitalization for a nervous breakdown. Hot tempered seaman Kenneth Doolittle burned and destroyed a large archive of her art. John Rothschild left his wife for her, but she did not commit to him. Perhaps he reminded her too much of her more conventional Pennsylvania background. Jose Negron, a salsa band leader, pictured here in 1936, left his wife for Neel but interestingly, she ended up using her as a subject.

Not long after they got together, they moved to Spanish Harlem and she began the prolific, clear eyed rendering of her friends and neighbors that is such an important part of the exhibition. They had a child, Richard, together (originally called Neel!) but Negron moved on a few years later to another woman.

The libertinage of the age went along with the politics, and the artistic milieu. Inevitably, there was collateral damage. But at the Met, we see the affection she once bore for her lovers in her indelible portraits. West coasters take heart: the show comes to the deYoung in 2022.

Jose1936, Estate of Alice Neel

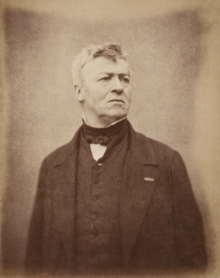

Berthe Morisot and Manet

Image credit: @clevelandmuseumofart

There are so many affecting things about Manet’s portrait of his sister-in-law, painter Berthe Morisot, begun in 1869. It's winter. Morisot is wearing a fur coat and muff and a violet hat of velvet trimmed with grey plumes. Manet painted her 11 times over many seasons and with many hats. He was fashionable and so was she. He was famously popular with the ladies and is the one who introduced her to his brother.

She was a supposed great-niece of Fragonard's so painting was already in the family. They met copying paintings at the Louvre. But Morisot in fact was the one who introduced Manet to Degas, Monet, Renoir and Cezanne among others in her circle. Her plein air painting had a great influence on him.

At the time of the portrait, Morisot was still mostly working in watercolors. But at the age of 23 she was accepted at the career defining Salon in 1864. Yet there is a certain tentativeness, an almost nervous energy one can still see five years later. Morisot had trouble convincing her parents to let her pursue a serious career.

Violet was a color Manet associated with her. The touches of violet become still more pronounced in a well loved later painting he did of her with a bouquet of violets after her father had died. Though this portrait is a lot tamer than the Dejeuner sur L'Herbe or the Olympia which had made his reputation, it still has the intensity of that work. It has a dynamic, fleeting quality that was certainly impressionistic, yet had hallmarks of his signature style where figures emerged from the black. He kept this portrait throughout his life.

Cecily Brown

The legend of the British-born painter Cecily Brown has been carved into the lore of contemporary art. After three decades of steady validation this former renegade of the London art scene has allowed herself to come full circle in two simultaneous exhibitions. A commission from Blenheim Palace, returns her to England-- And an exhibition of “Bedroom Paintings” at Paula Cooper Gallery returns her to intimacy. A new monograph exploring her formation and oeuvre, out this month from Phaidon completes the picture.

Unlike Pablo Picasso or Lucian Freud, who depended on a ready succession of live muses, the inspirations for Brown’s performative practice have been works by long-dead artists and contemporary iconography. Her fairy godfathers have included Francis Bacon, Goya, Gorky, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Delacroix, and Philip Guston.

At Blenheim, the good girl gone bad, provoking the art world with her early erotic and sexually violent imagery which first brought her to the attention of Deitch and Larry Gagosian, seems far away. Here her inspirations include the 16th-century Flemish painter Frans Snyders, Richard Dadd, and the 18th-century Sir Joshua Reynolds. In the “Bedroom Paintings” at Cooper, Brown revisits the edgy intimacy of bodies after many years away from this signature subject.

Brown resists categorization between figuration and abstraction and the new paintings walk the tightrope. She is fiercely dedicated to experimentation. “You have to be able to risk losing it,” she has said. Still, as Francine Prose suggests in her essay for the new Phaidon monograph on her, whereas we might once have invoked Bosch or Brueghel when we studied Cecily Brown, “now we think of a Cecily Brown painting when we look at the Bosch or Brueghel.” A great tribute to an artist who once thought she was doing everything wrong.

Phillip Guston

There has been a great deal of press, largely negative, on the decision of four major museums to postpone this Philip Guston retrospective. They don't say it's because of his Klan images, but that's what it's about. Though Jerry Saltz comes down on a less hostile note, saying that the underlying institutions need to address a systemic bias along with this postponement, I'm afraid-after reading a great deal-- I land on the side of those who regret the momentous decision.

Often referenced in the stories has been what many regard as the first global incidence of turbulence in the Whitney Museum's decision to display Dana Schutz's Open Casket painting of Emmett Till. There too, I felt keenly the artist's intentions which were all to the good. Some say that is no longer enough.

Guston is not alive, and can't be canvassed, but his corpus and his history in Los Angeles as a young, committed political activist suggest that he would have been very disturbed by this decision; his daughter Musa says so and she would know. I love Guston--so does Schutz and so many artists who have derived both stylistic and narrative lessons from this bold artist who eventually went against the prevailing AbEx winds.

Dana Schutz

Dana Schutz's new solo show at The Thomas Dane Gallery in London, opening on the 16th, is a mix of works from 2019 and 2020. What a difference a year makes! This image, Bound, from 2019 has much of her signature frantic feeling but not the darker palette of her more recent works, tinged as they are, inevitably, with thoughts of pandemic armageddon. What is the young blonde with her downcast eyes and her chartreuse slip-ons pondering a la Rodin? How is she connected to the bug-like creature with a remote control in one hand and a bone in the other? Playing the iconography guessing game with Schutz's work is part of the fun. See my piece in Air Mail for the full story.

Dana Schutz

Bound, 2019

oil on canvas

223.5 x 223.5 cm.

88 x 88 in.

© Dana Schutz. Courtesy the artist; Petzel, New York; Thomas Dane Gallery; Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin.

Photo: Jason Mandella

Marseilles Manifesta

One international event that I am very sad to miss is Manifesta, the biannual disruptor that lands in a city, lately one that needs some help, and promotes interventions that engage the institutions of that city to effect change. This year that city is Marseilles, like Palermo, the site of the last Manifesta, a multicultural epicenter that has been greatly affected over many years by immigration, its port, and the diverse population it serves. This year the focus of the artistic interventions are the Home, The Refuge, The Almshouse, The Port, The Park and The School. The curators take a big bite, but generally the meal is nourishing and I found that unlike many other international events that are more like helicopters that swoop in and out, Manifesta hopes to break through to some lasting changes. Go to their website to see the full program, and the beautiful historic buildings juxtaposed with the future.

Louisiana Museum

Leonora Carrington, Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse) ca. 1937-38

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York © Leonora Carrington / VISDA 2020

Among the many devastations of Covid is the inability to see wonderful exhibitions that are finally opening, mostly abroad, though some domestically. One that I am especially sorry to miss is the Fantastic Women exhibition at the Louisiana Museum outside Copenhagen. To see the work of Meret Oppenheim, Leonora Carrington, Frida Kahlo, Dora Maar, Dorothea Tanning, Louise Bourgeois, Lee Miller and other international art stars all in one go would be a dream, a surreal dream at that. In the meantime, here are some of the jewels that I will alas miss.

Sophie Tauber Arp in a renaissance at Hauser and Wirth, online

Image courtesy of Hauser & Wirth.

A very bright spot in the online horizon is today's upload by Hauser And Wirth of the work of Swiss Sophie Tauber Arp. Like many women of the period of early 20th century, her multi disciplinary career as artist, painter, sculptor, textile designer, furniture and interior designer, architect and dancer has been obscured by her more famous husband, Hans Arp. She was hard to pigeonhole, at times a constructivist, a concretist, a dadaist, a Bauhausian. She died too young, a mishap with a stove. Her work looks joyous, restrained but somehow free-spirited and it's a pleasure to see it along with documents and photographs. See especially the little Pompadour, her charming puppets and costumes, a wood Marital sculpture she did with her husband and the video. Image courtesy of Hauser & Wirth.

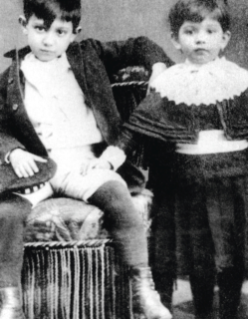

Lola Picasso at Sotheby's

Having worked as a producer on a PBS documentary on Picasso in conjunction with the grand Bill Rubin curated MoMA retrospective after his death, I thought I had seen so many of the early Picassos. But this beautiful one of 1901 of his younger sister Lola was new to me. Its provenance shows that it was first owned by Olivier Sainsere, one of Picasso's earliest collectors and later, by Paul Mellon. Her glance, which is both sober and haunting, is but one view of this very beautiful woman, but Picasso was still suffering from the death of his best friend Casagemas and was gradually working his way into his full-on blue period. Here the background is more muted and her left eye is almost drifting, looking towards something she too is possibly concerned about. But he image of her in her traditional black mantilla is ambiguous on that point.

I checked with Marilyn McCully, who had been an advisor on our film and who is considered the expert on Picasso's early Spanish years. She said, "Picasso was always close to his sister, and he kept up with her children later in life, when two of her sons left Spain at the end of the Civil War for France. She was married to a doctor called Juan Vilató and they had seven children: Fin and Xavier, both became artists. Lola and her husband eventually settled in Barcelona, and she became the “head” of the family, in a sense, after their mother died in 1939. As a girl, Lola was Picasso’s principal model, and she also did drawings in the late 1890s.This suggests that Picasso painted the little panel in Barcelona and then took it with him to Paris (there were other small works he brought with him) in the spring of 1901. There is no evidence this painting was in the Vollard show (the first 'big show’ which Sotheby's suggests it was). Auctions sometimes give us the chance for a glimpse of things we would never get to see otherwise, and this jewel of a painting is a prime example of that. It goes under the hammer tomorrow night.

Cecile Walton, a modern Millie artist in Glasgow of the 1920s

This self portrait riff by Cecile Walton on Manet’s Olympia replete with not very PC black Sambo doll instead of black cat and nurse instead of maid and baby standing in for flowers from 1920 shows just how screwed up referencing the masters can get. Walton was part of the Edinburgh group which prized symbolist motifs. That said, the title, Romance belies it’s matter-of-fact treatment of her two children as she gets her foot massage. Having just re-seen the actual Olympia at the Musee d’Orsay, one of their most respected paintings, I am hard pressed to even make the comparison. Yet I like this painting and wonder about the very forward thinking woman who painted it who has more or less disappeared into obscurity. She lived for a time in a menage a trois with her husband, Eric Robertson, also an artist, and alcoholic—obviously a problem of the period—and another artist Dorothy Johnstone when this work was painted. Hmmm……

The Ladies Waldegrave

Uncle Horace (Walpole) commissioned Joshua Reynolds to paint his nieces, the ladies Waldegrave, in 1780. Though they look to be purely Three Gracelike in their white dresses, making lace and spinning silk, the portrait was actually a come-hither to potential suitors for Charlotte, Elizabeth and Anna who were still single. It was the 18th century version of Tinder.

Corot's Women at the National Gallery: A penny for their thoughts

I am not an ardent fan of landscape, however beautifully wrought, so Camille Corot, one of the great 19th century practitioners has not been much on my radar.

All this changed when I saw the jpegs of 44 of Corot’s Women in the National Gallery exhibition which has just opened in DC. I have not seen them in their sumptuous flesh yet but I have seen the catalog and heard the curators talk. Many of the paintings are on loan from the Met, but as this is the only venue of the exhibition which has also aggregated other important works, it’s worth a special trip.

To be female in the 19th century was fraught. In France, Balzac, Zola and Flaubert were zeroing in on the dilemma of those of the fair sex who did not have the resources to maintain a position in society. You were either well-to-do, or poor, a milkmaid, a courtesan or princess. If you were beautiful, it helped but then you had a choice of how to deploy your resources. Sometimes that did not turn out so well.

The paintings do not reflect the down trodden. And yet being a model in those times was certainly not an upper class occupation. The question about what the models did besides model is ever present. Curator Mary Morton suggests they were not performing for Corot. Are they thinking about how hungry they are and how soon they will be able to eat after posing, or something more elevated?

Corot, like his peers, had also certainly come to depend on photography, the medium that had taken the century by storm, and had fostered the development of collections of erotica.

Yet like Delacroix, after touring Italy or southern regions, Corot portrayed the exotic woman in situ, in costume, fully attired. His portraits are often pensive, his nudes not nearly as confrontational as Manet’s who looked the viewers directly in the eye, daring them to respond. Though he played with the male gaze, my impression is of a certain chastity and remove, even in his splendid odalisques. Picasso was apparently quite taken with them.

Corot was by all accounts religious and devoted to his mother and sister with whom he lived. Possibly asexual. He swore off marriage. His family had the resources to allow him to become an artist and finally with their blessing, after his sister’s death, he did so. His family were bourgeois wigmakers and hat makers and he had worked as a draper. Though he was reportedly very shy and wary of the female clients, he obviously had occasion to observe them in close quarters when they were at ease.

I have seen the sumptuous and thrilling Delacroix show in Paris now largely arrived at the Met. Delacroix is a favorite and I have to confess that Delacroix’s portraits of women are even more splendid.

But Corot captures something else. Not patriotism or sensuality, but a haunting interiority, a penny for their thoughts.