Having worked as a producer on a PBS documentary on Picasso in conjunction with the grand Bill Rubin curated MoMA retrospective after his death I thought I had seen so many of the early Picassos. But this beautiful one of 1901 of his younger sister Lola was new to me. It's provenance shows that it was first owned by Olivier Sainsere, one of Picasso's earliest collectors and later, by Paul Mellon. Her glance, which is both sober and haunting, is but one view of this very beautiful woman but Picasso was still suffering from the death of his best friend Casagemas and was gradually working his way into his full-on blue period. Here the background is more muted and her left eye is almost drifting, looking towards something she too is possibly concerned about. Auctions sometimes give us the chance for a glimpse of things we would never get to see otherwise and this jewel of a painting is a prime example of that.

Lola Picasso at Sotheby's

Having worked as a producer on a PBS documentary on Picasso in conjunction with the grand Bill Rubin curated MoMA retrospective after his death, I thought I had seen so many of the early Picassos. But this beautiful one of 1901 of his younger sister Lola was new to me. Its provenance shows that it was first owned by Olivier Sainsere, one of Picasso's earliest collectors and later, by Paul Mellon. Her glance, which is both sober and haunting, is but one view of this very beautiful woman, but Picasso was still suffering from the death of his best friend Casagemas and was gradually working his way into his full-on blue period. Here the background is more muted and her left eye is almost drifting, looking towards something she too is possibly concerned about. But he image of her in her traditional black mantilla is ambiguous on that point.

I checked with Marilyn McCully, who had been an advisor on our film and who is considered the expert on Picasso's early Spanish years. She said, "Picasso was always close to his sister, and he kept up with her children later in life, when two of her sons left Spain at the end of the Civil War for France. She was married to a doctor called Juan Vilató and they had seven children: Fin and Xavier, both became artists. Lola and her husband eventually settled in Barcelona, and she became the “head” of the family, in a sense, after their mother died in 1939. As a girl, Lola was Picasso’s principal model, and she also did drawings in the late 1890s.This suggests that Picasso painted the little panel in Barcelona and then took it with him to Paris (there were other small works he brought with him) in the spring of 1901. There is no evidence this painting was in the Vollard show (the first 'big show’ which Sotheby's suggests it was). Auctions sometimes give us the chance for a glimpse of things we would never get to see otherwise, and this jewel of a painting is a prime example of that. It goes under the hammer tomorrow night.

An homage to Picasso's Women and biographer John Richardson at Gagosian

Pablo Picasso, Buste de femme (Dora Maar), 1940, Oil on canvas, 29 1/8 x 23 5/8 in, 74 x 60 cm, © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York, Photo: Erich Koyama, Courtesy Gagosian

When I corresponded with Dora Maar to try to pin her down for an interview for our WNET Picasso documentary at the time of last major Picasso retrospective at MoMA, she was slippery but made sure to ask after John Richardson's whereabouts as she wanted to reconnect with him. She was a tough get, but he got her.

A newly opened homage to Richardson, Picasso's biographer, is also a testament to Gagosian's ability to pull together so many important images in record time. Some of the images of Marie Therese appeared in the Tate Modern retrospective last year. But others felt new to me. Perhaps it’s because I see these images in a slightly different way each time. Recently I too have been examining the role of the women in Picasso’s life and work.

To that end, I often revisit Richardson/Picasso and I'm always impressed by the wealth of personal detail and the profound sense of humor that he brought to this artist, the most chameleon-like of subjects. Richardson organized a number of electric Picasso shows at Gagosian and though this is a less ‘curated’ affair, it still invokes the complex relationships he had with so many of his lovers/muses/wife.

The last upcoming volume of his Picasso biography which will be published posthumously will surely add more delicious tidbits as well as enormous scholarship and I eagerly await it.

John Richardson dies at 95, a biographer of Picasso equal to his lifelong subject

The following is an excerpt from my Huffington Post piece on Volume III of Richardson’s Picasso biography.

…All the more reason then to be worshipful and impressed at the astounding work of John Richardson who has produced the third volume of his biography of Picasso, The Triumphant Years, published this week to great acclaim. Richardson’s unflagging erudition, meticulous reporting, insatiable digging, clever connections, and vast and deep personal knowledge of the players makes this series much closer to a performance piece of biography , the definitive text.

And because Richardson makes it perfectly clear with engaging narrative and precise scholarship how worthy his subject is, even those who have read about Picasso before will be newly swept away by the intricacies of this complex character. This is not, however, just a tome for insiders, though it helps to have a healthy interest in art and artists.

Richardson met Picasso while living with Douglas Cooper (who had himself wanted to write the biography) in the south of France and saw him regularly from the early fifties through the early sixties. He began by thinking he would write about the wives and mistresses of Picasso, the way the artist used art and sex, painting and making love, as metaphors for each other and how the style of his work changed as he changed women—volatile relationships that Dora Maar, herself one of the mistresses, characterized to him as ‘first, the plinth, then the doormat”. This was the template we used on the film, (WNET, Picasso, A Painter’s Diary) and it’s reductive and catchy, certainly one way to process the gargantuan archive when you only have ninety minutes.

But as Richardson himself says, “Picasso’s work is far too protean and paradoxical to be limited to a single reading.” And so he abandoned that seductive narrowcasting at the outset in favor of a much more comprehensive and penetrating approach.

One that would more or less take the rest of his life.

Richardson isn’t the first to devote most of his life to Pablo, as the volumes make clear. The Picasso bibliography includes everything from kiss and tells to scholarly treatises about the work and any number of memoirs and biographies. (Richardson is impatient and dismissive of some of these earlier efforts, calling them everything from “unreliable” to “rigamarole” or “fairy tale” to outright “wretched” or “sheer fantasy”.) But his end result is entirely different. Encyclopedic without being boring, any future artist’s biography, or really any biography, will inevitably have to step over Richardson’s very high bar.

Occasionally, biographers manage to be fans of their subjects for the duration. It’s hard to love someone unreservedly whom you come to know so intimately— Richardson doesn’t shy away from scandal, rather he is propelled by it, and sometimes, if this works to Picasso’s disadvantage, so be it. Looking at a life from the perspective of the warts and all can produce battle fatigue but at the end of the third volume (the ballets, the project for a memorial to Apollinaire, the bourgeoise life with Olga, the flirtation with Sara and Gerald Murphy, the rebellious hedonism of his attraction to the seventeen year old Marie Therese) with Picasso shrugging off Surrealism and heading for the shattering Guernica, one still feels Richardson’s magnificent enthusiasms for the moods, the settings, the entourages that may have influenced him; the motivations, the myth-busting, the sexual/historical/empirical digressions often taking us far afield only to bring us back a bit later with a much richer understanding of what made this man, and his world, tick.

The volumes look and are dense, (Volume 1 ranges from 1881-1906, Volume 2 from 1907- 1916 and Volume 3 from 1917-1932) but they are intensely readable—chatty, personal, with mini- biographies of others in the Picasso circle—so that we come to know just how convoluted and complex the roots of the art were with Pablo often devouring the hands that were feeding him. The tangents, however “vaut le detour” and are every bit as juicy as the three star view of the man himself. Often, Richardson makes patently clear, Picasso was conceptually leagues ahead of everyone else. But at times he was in debt to other geniuses who were his friends and competitors-Braque, Gaugin, Matisse, Seurat—and to the other protean talents from whom he freely stole(Manet, Ingres) ideas and images.

The normally heavy lifting of biography thus seems like gossamer in his hands, the facts arranged in such a way as to ease you on down the road with the tone of a confidence or a wink. The iconography of each important work is disarmingly traced, threading the personal and professional antecedents into one comprehensive whole. There are no sacred cows for Richardson—and like a cat he sneaks up and circles the truth and then pounces on it, explaining the artistic breakthroughs, the changes from one style to another, the sexuality and drugs which fueled some of them, and Picasso’s own drama-king ego that self-mythologized to the point that he came to believe in the stories too. As a myth debunker Richardson, however, is unsurpassed, adroit at peeling the layers: first, those of Picasso himself, then the second generation contemporary witnesses who often rewrote history, then the third generation anecdotal whispers, the fourth generation scholarly reckoning, and so on, often a daisy chain of prior confabulation.

Richardson leaves no dwelling, no voyage, no influence (the wonders he saw and appropriated into his own work), no woman, no friend , or enemy uncharted. One resists the tendency to makes lists only with difficulty: the houses (in Volume Three alone: Montrouge, rue la Boetie, le Gueridon, La Vigie, la belle Rose, la Haie Blance, Boisgeloup), the Women (madcap Fernande, lissome Eva, bourgeoise Olga, , sexpot Marie Therese, free spirited Francoise, imposing Jacqueline), the friends (Apollinaire, Cocteau, Jacob, Breton, Gertrude Stein, Stravinsky, Diaghilev) and the enemies and some that straddled the two camps, the Dealers (Kahnweiler, Rosenberg), the ballets (Parade, Tricorne, Pulcinella, Mercure, L’epoque des Duchesses, La Danse), the Museums, (besides Paris, Antibes, Barcelona and now Malaga) the Galleries, the retrospectives and exhibitions, the media (paint, sculpture, photography, poetry, collage, tapestry). All come under his watchful, painstaking and often bemused eye.

Richardson’s gift for language also has the added bonus of a mini-tutorial in French and Spanish slang —gratin (high society), bien couillarde (ballsy, or well hung), tertulia (group of friends).

And as far as wrangling goes, Richardson is unrivaled. Some of the images were a revelation to me; many classified or in private collections that were being carefully concealed at the time of the documentary but his long personal cultivation of so many of the Picasso personages has reaped its rewards and the astonishing selection of photographs from the Olga years in Volume Three is testament to this.

Richardson notes that for most of his life, Picasso was already in the spotlight, that the tributes and retrospectives one normally gets at the end had been ongoing since his twenties. Little details, why Picasso’s black was blacker than black (he added silver powder) or his relationship with Chanel (one night stands) make the reading lively. But it also helps to be reminded of his early genius, the sheer power of his intellectual and instinctive audacity—the breakthrough Demoiselles D’Avignon for example,was painted when he was 25!

In short, Richardson seems to have found a way to see Picasso plain while at the same time respecting his obviously century-dominating genius. Fernande, an early “official” mistress apparently said, “He who neglects me, loses me” and Picasso might well have intimated the same thing. Fear not, Richardson has made amply sure we won’t.

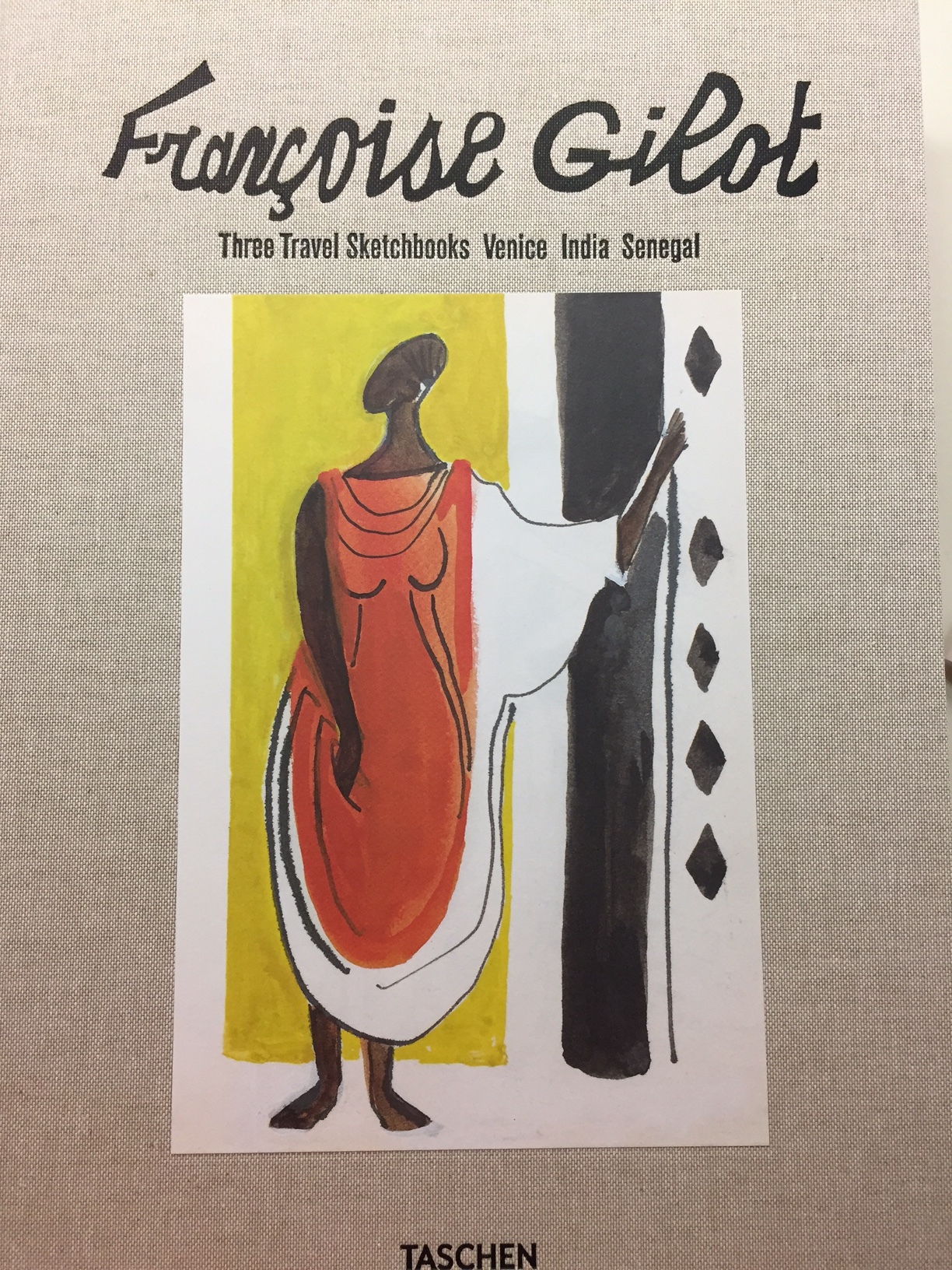

The Sketchbooks of Francoise Gilot: life went on after Picasso

I worked on a film biography for PBS on Picasso in conjunction with MoMA’s first comprehensive retrospective after Picasso’s death. William Rubin, the chief curator of MoMA, who was organizing the exhibition was adamant we not interview Francoise Gilot because he was very concerned about getting loans from Picasso’s widow Jacqueline who was controlling an important part of his estate and he thought contact with Gilot might jeopardize that, given the acrimony with which Picasso and Gilot had landed after her 1964 tell all memoir about her life with him.

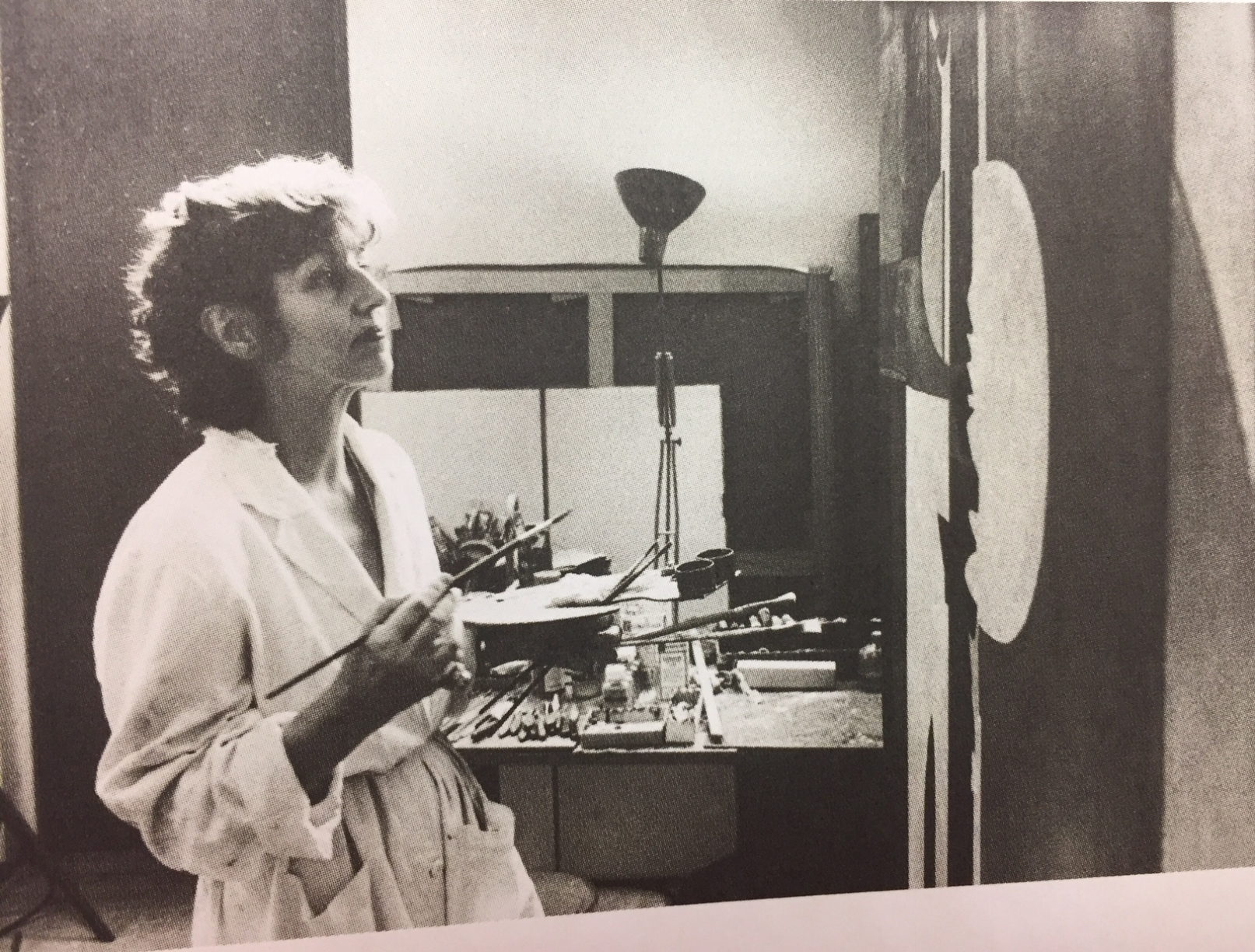

I had read Life with Picasso and thought it not only bold but instructive. It told how to hold your own with a powerful man. I came away admiring the only woman who had been able to extricate herself from Picasso and go on and have a productive life. I fought for her inclusion in the film, but I was very junior and had no say.

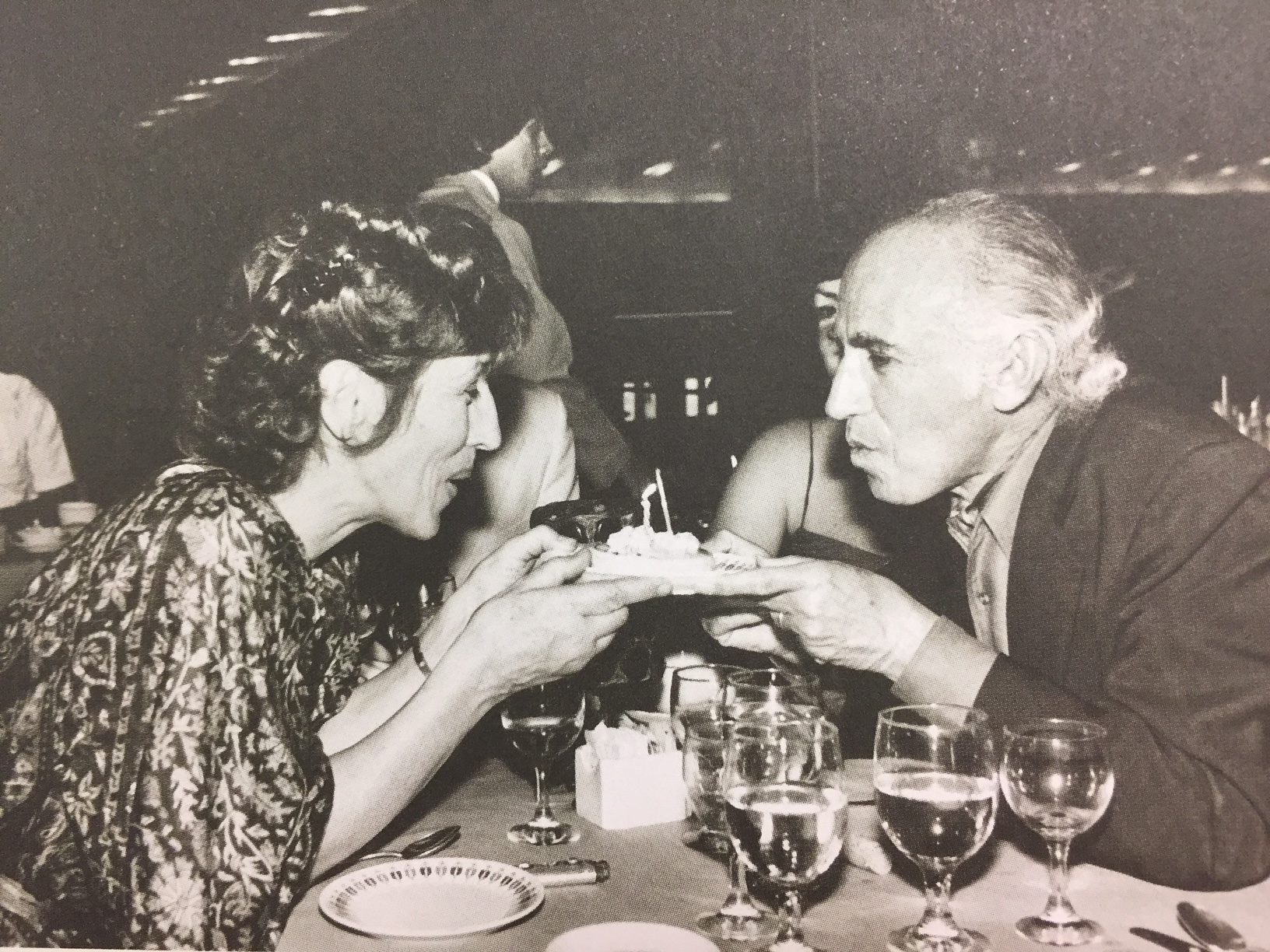

Though I did spend time with Claude and Paloma her children, it wasn’t until 2012 on the occasion of her show at Gagosian Madison that I finally got to meet her. She was on the arm of John Richardson, Picasso’s biographer, who is still working on the last volume of his definitive series on the life. Frail but steely is how she came across to me.

For a long time I had not admired her work as much as her person.

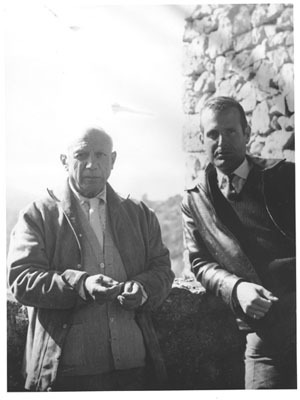

But having now received the new Taschen set of three sketchbooks she made while on travels to Venice India and Senegal, I am newly taken with it. These more spontaneous drawings, watercolors and make for a window into this remarkable woman that is a fresh look at the open, attentive, original way she has seen the world.

Gilot was a young artist when she met Picasso at 21, an acolyte. Inevitably, there has always been Picasso in her work. That’s not being revelatory. There is something of Picasso in almost every artist who worked in the 20th and 21st centuries.

But it is Matisse she invokes in these sketchbooks. She says he was the painter she felt closest to. That would have driven Picasso, who felt Matisse was his most important rival, crazy.

The Taschen series, 1974-1981, is a lively, colorful pictorial diary of her exotic travels. They began when she traveled with Jonas Salk, having moved on from an artistic genius to a scientific one (there was photographer Luc Simon in between). Francoise was both a companion to famous men (some women have a talent for that) and an artist who was able to maintain her own practice even in the midst of these larger lives.

“These little books are complete in themselves,” she says. “I made them, and then once I’d made them I was free. For me these little books are a step toward freedom.”