The following is an excerpt from my Huffington Post piece on Volume III of Richardson’s Picasso biography.

…All the more reason then to be worshipful and impressed at the astounding work of John Richardson who has produced the third volume of his biography of Picasso, The Triumphant Years, published this week to great acclaim. Richardson’s unflagging erudition, meticulous reporting, insatiable digging, clever connections, and vast and deep personal knowledge of the players makes this series much closer to a performance piece of biography , the definitive text.

And because Richardson makes it perfectly clear with engaging narrative and precise scholarship how worthy his subject is, even those who have read about Picasso before will be newly swept away by the intricacies of this complex character. This is not, however, just a tome for insiders, though it helps to have a healthy interest in art and artists.

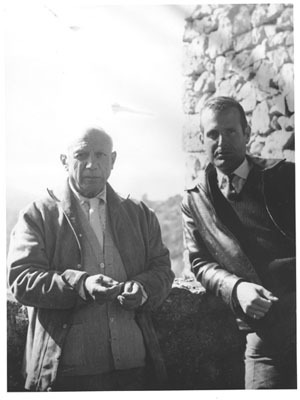

Richardson met Picasso while living with Douglas Cooper (who had himself wanted to write the biography) in the south of France and saw him regularly from the early fifties through the early sixties. He began by thinking he would write about the wives and mistresses of Picasso, the way the artist used art and sex, painting and making love, as metaphors for each other and how the style of his work changed as he changed women—volatile relationships that Dora Maar, herself one of the mistresses, characterized to him as ‘first, the plinth, then the doormat”. This was the template we used on the film, (WNET, Picasso, A Painter’s Diary) and it’s reductive and catchy, certainly one way to process the gargantuan archive when you only have ninety minutes.

But as Richardson himself says, “Picasso’s work is far too protean and paradoxical to be limited to a single reading.” And so he abandoned that seductive narrowcasting at the outset in favor of a much more comprehensive and penetrating approach.

One that would more or less take the rest of his life.

Richardson isn’t the first to devote most of his life to Pablo, as the volumes make clear. The Picasso bibliography includes everything from kiss and tells to scholarly treatises about the work and any number of memoirs and biographies. (Richardson is impatient and dismissive of some of these earlier efforts, calling them everything from “unreliable” to “rigamarole” or “fairy tale” to outright “wretched” or “sheer fantasy”.) But his end result is entirely different. Encyclopedic without being boring, any future artist’s biography, or really any biography, will inevitably have to step over Richardson’s very high bar.

Occasionally, biographers manage to be fans of their subjects for the duration. It’s hard to love someone unreservedly whom you come to know so intimately— Richardson doesn’t shy away from scandal, rather he is propelled by it, and sometimes, if this works to Picasso’s disadvantage, so be it. Looking at a life from the perspective of the warts and all can produce battle fatigue but at the end of the third volume (the ballets, the project for a memorial to Apollinaire, the bourgeoise life with Olga, the flirtation with Sara and Gerald Murphy, the rebellious hedonism of his attraction to the seventeen year old Marie Therese) with Picasso shrugging off Surrealism and heading for the shattering Guernica, one still feels Richardson’s magnificent enthusiasms for the moods, the settings, the entourages that may have influenced him; the motivations, the myth-busting, the sexual/historical/empirical digressions often taking us far afield only to bring us back a bit later with a much richer understanding of what made this man, and his world, tick.

The volumes look and are dense, (Volume 1 ranges from 1881-1906, Volume 2 from 1907- 1916 and Volume 3 from 1917-1932) but they are intensely readable—chatty, personal, with mini- biographies of others in the Picasso circle—so that we come to know just how convoluted and complex the roots of the art were with Pablo often devouring the hands that were feeding him. The tangents, however “vaut le detour” and are every bit as juicy as the three star view of the man himself. Often, Richardson makes patently clear, Picasso was conceptually leagues ahead of everyone else. But at times he was in debt to other geniuses who were his friends and competitors-Braque, Gaugin, Matisse, Seurat—and to the other protean talents from whom he freely stole(Manet, Ingres) ideas and images.

The normally heavy lifting of biography thus seems like gossamer in his hands, the facts arranged in such a way as to ease you on down the road with the tone of a confidence or a wink. The iconography of each important work is disarmingly traced, threading the personal and professional antecedents into one comprehensive whole. There are no sacred cows for Richardson—and like a cat he sneaks up and circles the truth and then pounces on it, explaining the artistic breakthroughs, the changes from one style to another, the sexuality and drugs which fueled some of them, and Picasso’s own drama-king ego that self-mythologized to the point that he came to believe in the stories too. As a myth debunker Richardson, however, is unsurpassed, adroit at peeling the layers: first, those of Picasso himself, then the second generation contemporary witnesses who often rewrote history, then the third generation anecdotal whispers, the fourth generation scholarly reckoning, and so on, often a daisy chain of prior confabulation.

Richardson leaves no dwelling, no voyage, no influence (the wonders he saw and appropriated into his own work), no woman, no friend , or enemy uncharted. One resists the tendency to makes lists only with difficulty: the houses (in Volume Three alone: Montrouge, rue la Boetie, le Gueridon, La Vigie, la belle Rose, la Haie Blance, Boisgeloup), the Women (madcap Fernande, lissome Eva, bourgeoise Olga, , sexpot Marie Therese, free spirited Francoise, imposing Jacqueline), the friends (Apollinaire, Cocteau, Jacob, Breton, Gertrude Stein, Stravinsky, Diaghilev) and the enemies and some that straddled the two camps, the Dealers (Kahnweiler, Rosenberg), the ballets (Parade, Tricorne, Pulcinella, Mercure, L’epoque des Duchesses, La Danse), the Museums, (besides Paris, Antibes, Barcelona and now Malaga) the Galleries, the retrospectives and exhibitions, the media (paint, sculpture, photography, poetry, collage, tapestry). All come under his watchful, painstaking and often bemused eye.

Richardson’s gift for language also has the added bonus of a mini-tutorial in French and Spanish slang —gratin (high society), bien couillarde (ballsy, or well hung), tertulia (group of friends).

And as far as wrangling goes, Richardson is unrivaled. Some of the images were a revelation to me; many classified or in private collections that were being carefully concealed at the time of the documentary but his long personal cultivation of so many of the Picasso personages has reaped its rewards and the astonishing selection of photographs from the Olga years in Volume Three is testament to this.

Richardson notes that for most of his life, Picasso was already in the spotlight, that the tributes and retrospectives one normally gets at the end had been ongoing since his twenties. Little details, why Picasso’s black was blacker than black (he added silver powder) or his relationship with Chanel (one night stands) make the reading lively. But it also helps to be reminded of his early genius, the sheer power of his intellectual and instinctive audacity—the breakthrough Demoiselles D’Avignon for example,was painted when he was 25!

In short, Richardson seems to have found a way to see Picasso plain while at the same time respecting his obviously century-dominating genius. Fernande, an early “official” mistress apparently said, “He who neglects me, loses me” and Picasso might well have intimated the same thing. Fear not, Richardson has made amply sure we won’t.