Though she is not on view at the Met right now, La Carmencita, another enchanting flamenca from John Singer Sargent in 1890, sits in a postcard on my desk, daring me each morning to greet the day with fiery resolve. In my view she is infinitely more elegant and compelling than most on the red carpet last night

The Met says Sargent may have encountered her at the 1899 Expo in Paris, which was so important to art and to engineering. He apparently was utterly captivated and called her a "bewildering superb creature". She came to NY the following year and 'took New York by storm’".

She was a 'restless and demanding sitter' which makes sense: flamenco dancers are happiest when they are dancing a solea or buleria. He made many studies of her dancing, but then opted to portray her in a stationary pose.

It seems that critics were divided-how dare he represent "a common music hall performer in such a monumental way."

Though her face is rendered quite white, she is not as blanched as Madame X, who was to come a few years later, but her arrogant, frontal look is more daring than Madame X’s who although was upper class and dressed more revealingly is turned away from the artist as if to hedge his, and her, bets.

Gerhard Richter at the Met Breuer

The Gerhard Richter show will be the last of the Met's in the Breuer building. Next time your'e there it will be part of the Frick, a giant pop up now to different large neighboring institutions. It is a retrospective, yes, but I had trouble finding the 'there-there' . There are indeed some important works, more of the recent than earlier. but one sees a career that like Picasso's with its many style changes and different families takes some complementary narrative. Mysterious horizontal brush work is a unifying theme. Wall labels are all important as the show seems organized both by subject matter and period. It's impossible to get Florian Von Donnersmarck’s film Never Look Away out of your head which was the biopic that Richter cooperated with and then rejected but which did give some context to the life. There's a video on the Met website that is very good. These are my favorites. Go to the Met website for more images as the show is alas now closed.

Photos courtesy Met Breuer.

Michelangelo stays at the Met

For the few years I worked at the Services Culturels housed in the former Payne Whitney mansion across from the Metropolitan Museum on Fifth, we used this rather nondescript statue as a coat or hat rack, ashtray, or place to wad a used cocktail napkin. When it was discovered to be a vrai Michelange I was rather nonplussed. My office which was vaguely like a bordello with a white shag rug and dark walls in a remade attic space was only one of many odd nooks in the building which Miss Helen Whitney had done up when upper Fifth was the boonies. Still the statue conferred a sense of decorum and history during a time of my life dearly lacking in same.

Goddesses at the Met

Inlaid with rubies in her eyes and navel as was the occasional special custom for Mesopotamian deities, this petite, exquisite 1st century BC-1st century AD standing nude statue in the Met Museum’s World Between Empires show of Middle Eastern treasures—and their horrific destruction by Isis--raises questions of divine identity. Is she a Greco-Roman Venus goddess of beauty and love or, as one curator suggests, Ishtar of Babylon who was closer to home? One other similar example of this kind of statue lay on her side easily recalling the many Olympias of the 19th century. Having just attended a Paola Antonelli salon at MoMA on ‘White Men”, I wondered why alabaster queens were the symbol of a middle eastern cultures? The statue is on loan from the Louvre where even in her diminutive state she could outshine the Mona Lisa

Images courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Lucio Fontana: On the Threshold at the Met Breuer

Lucio Fontana: On the Threshold at the Met Breuer comes at the proper moment. We are all ready to pierce and slash things right now, and Fontana gives us a vision of how we might do that and also produce beauty. What better metaphor for our times?

In his early years, Fontana, an Argentinian-Italian hybrid, made wonderful sculptures with a rare freedom both in form and color also riffing on the Majolica which was omnipresent (they oddly reminded me of Dana Schutz’s new series). His work was popular almost right away and he received a commission on the Life of the Sea, which showed his affinities for the natural world. They were to be totally obscured in the later work.

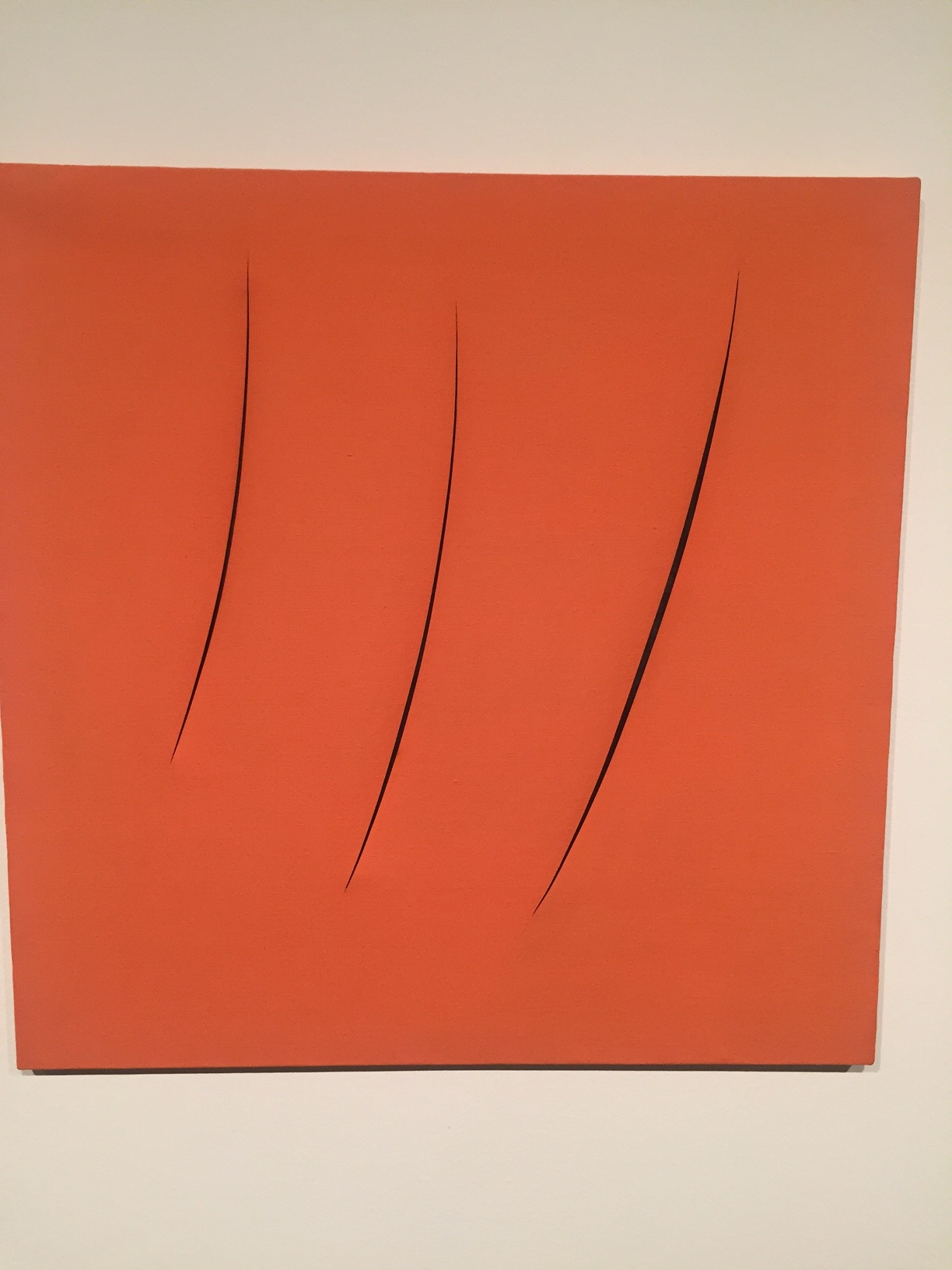

He is particularly famous for two series that broke through the picture plane.

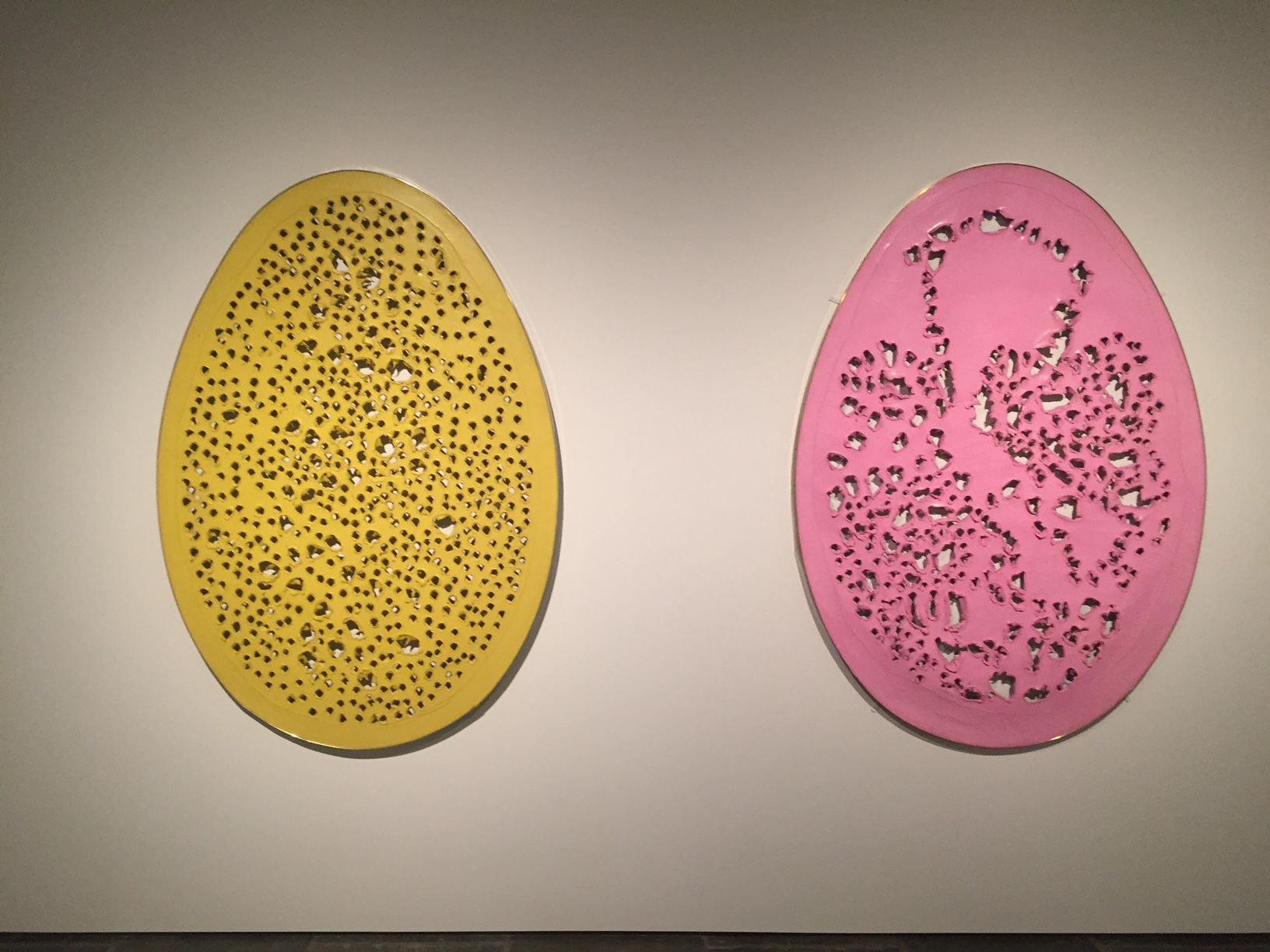

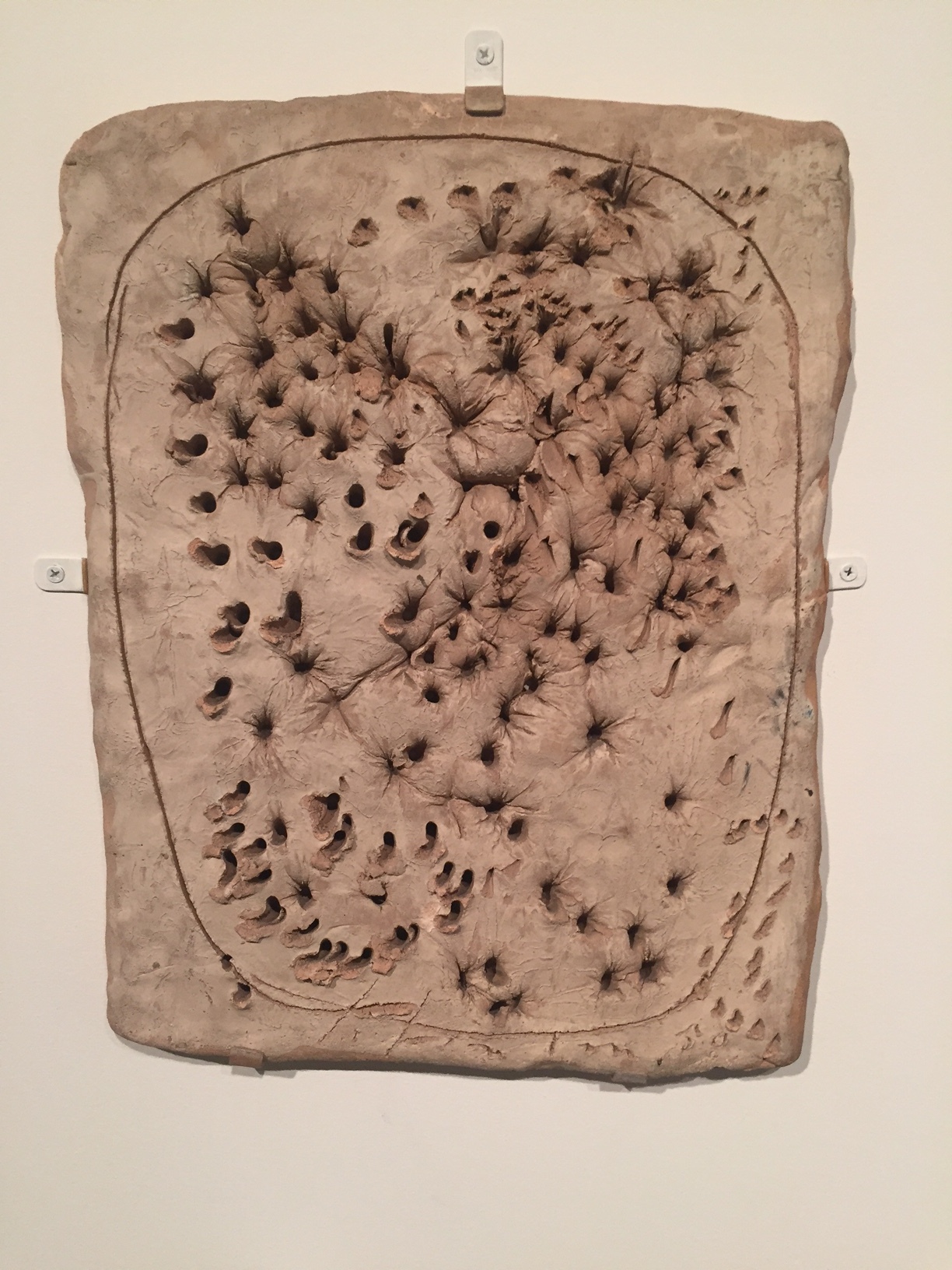

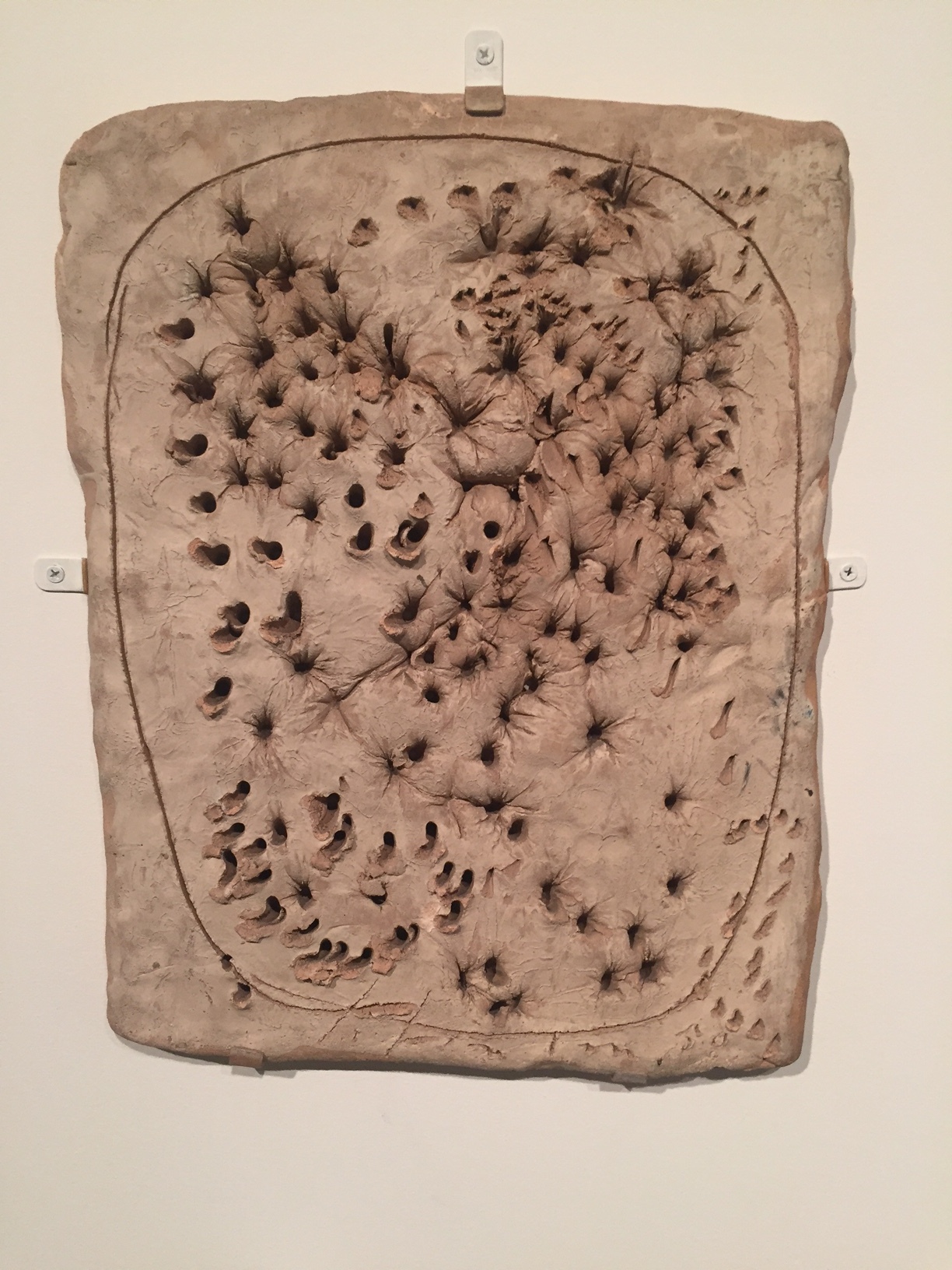

The ‘Concetto spaziale,’ which were first conceived as screens for the transmission of light, display holes punched in patterns on canvas connecting us to the void, the infinite, the 4th dimension.

The early gallery of these, without chroma, but instead a kind of washed out beige, are so very pure.

I feel like my heart is being pierced. Somehow they made me think of Janis Joplin’s lyric “Take a little piece of my heart now baby.”

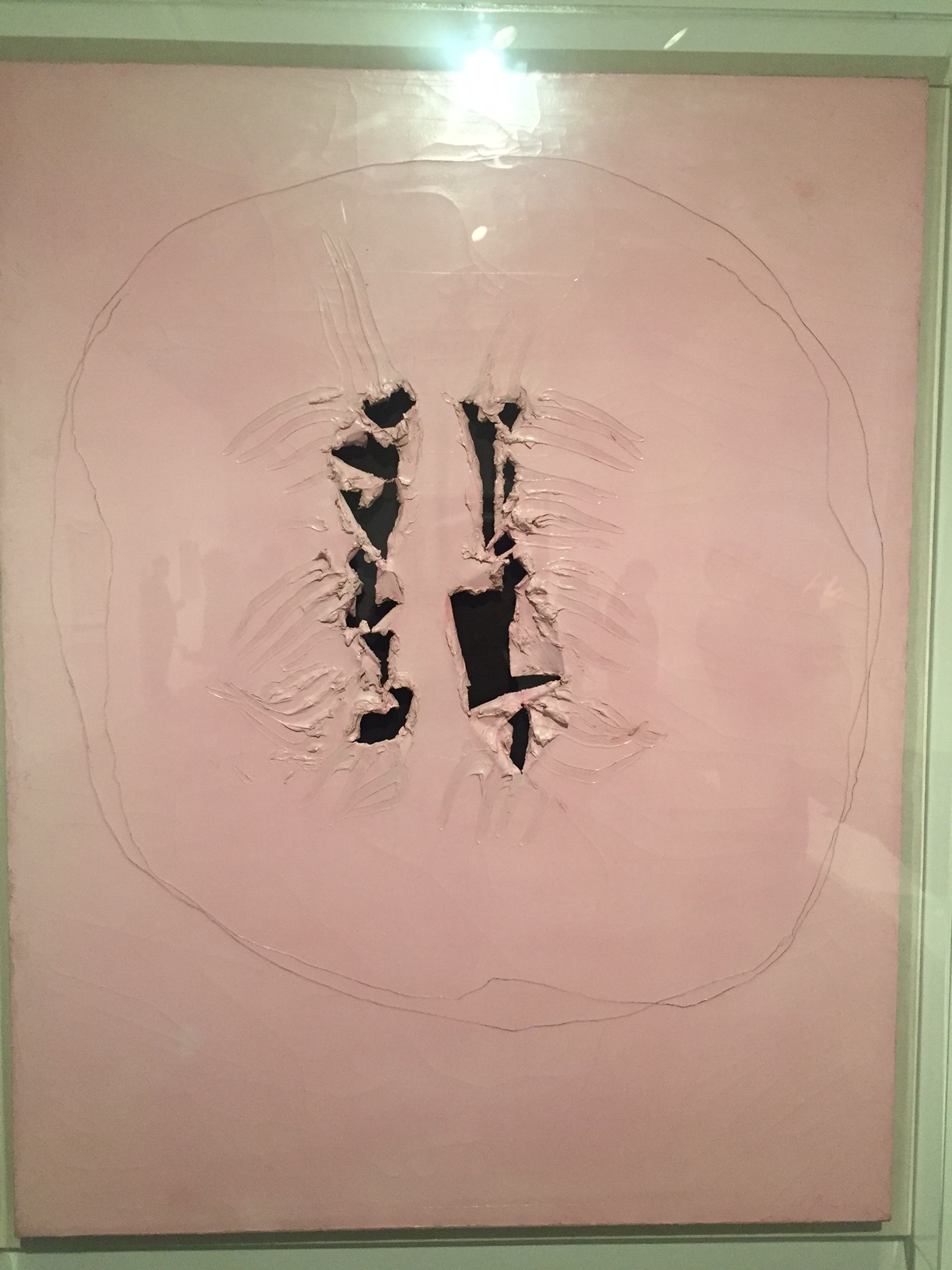

Later, he added chroma, glass and stone and the paintings grew larger, but those don’t have the same resonance. There is actually a pink painting that looks like the cavity of the chest—perhaps too literal.

His “Cuts” series was considered his most radical, acts of sabotage painting. These are likely the ones you are more familiar with. Fontana said it was as hard to decide where to put the cuts as anything else he had done, and that he then folded them back and affixed them to the back of the canvas. No more fenestration as with the holes—just violent fissures. Once again, it’s impossible not to think of our contemporary social and political anguish.

A decade later, he had cycled through color and come back to white, using house paint because it was flatter.

Fontana has come back into vogue along with his compatriots Alberto Burri and Piero Dorazio and the mid-century school of Italian painting, design and architecture. Here at the Met we have the reason why.

January 23 - April 14, 2019.