I had written about two shows at SF MoMA that I hadn’t been able to see due to pandemic. Finally I got to see them. Though I had been deep into the Joan Mitchell archive and bio this summer, I was still unprepared for the riotous color and wild abandon of the work and its very emotional effect. One photo of Mitchell (far right) with other members of the Saddle and Cycle club in Chicago of 1935 when she was only 10 years old reminded me that even as she declared for poetry or painting at an early age, her autocratic father, though determined she should be exposed to art, had pushed her towards more socially acceptable pursuits like riding and ice skating. In this colorized photo that appeared in the local paper, Mitchell already stands out with her slouchy pose and ubiquitous glasses. All eyes are on her.

Diego Rivera's Art in Action

The WPA was not the only entity commissioning work. The Art in Action program hosted by the 1940 season of the Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island in the SF Bay invited Diego Rivera to design a mural for the SF City College. As in his mural for Rockefeller Center, Rivera’s politics got in the way until 1961 when it was finally installed in the college’s performing arts center. Now it is newly installed SF MoMA and though I had seen the install in progress the wow factor is all the more thrilling as it’s now complete. It is in impeccable condition and it takes the handy guide they have prepared to really dial in on the many referents to the topic of unity. Frieda Kahlo is front and center. She was with Rivera in SF while he was working finding her way in her own work. It is a masterpiece-a marriage of art and life. (That’s Paulette Goddard wife of Chaplin holding hands with Rivera practically under Frieda’s nose in the third panel. Pan American unity he said👀)

Learning About Joan Mitchell

My story about Joan Mitchell's life and work timed with the retrospective of her work at SF MoMA opening this week appeared in Air Mail News over the weekend. In learning more about Mitchell, I began to see beyond her fairly reductive reputation as a very talented but very volatile artist.

I hadn't understood how her childhood, while privileged, had betrayed her earliest impulses towards art and poetry and that she had to fight her way past a controlling father to be able to study art and reject the life of an ice skating princess.

I didn't know that she had helped her first husband, Barney Rosset, who went on to become a fearless publisher, imbue new life into Grove Press. And that her other relationships with men who were also painters were fraught. Mitchell was not great at commitment to anything but her work.

Mitchell felt she had to be as tough as one of the guys to be taken seriously. At the time, even among the other strong women of the Abstract Expressionist movement in the 50's, this was unusual.

I hadn't realized that the pull of Paris and of France, where she ended up living, was at first a place where she felt uninspired. She bought a property where Monet had lived, and she both enjoyed and, at times, resented the connection.

Most importantly, I hadn't known that her dramatic paint strokes and large canvases had been inspired by artists like Van Gogh and Cezanne, and had roots in the sunflowers and bridges that she could see from her window. That she remembered landscapes and didn't need to have them in front of her. And that her abiding painterly energies went towards expressing the feelings that she had--and not some 'abstract' idea of things. Joan Mitchell opened my eyes. Link to the story in my bio.

Photo: Loomis Dean, Life Picture Collection

James Weeks Paints Out of His World

James Weeks is not a name that will immediately bring an image to mind for most people. Yet his painting, though quite different, and more formal than Park, Bischoff and Diebenkorn has a very contemporary look. His role in Bay Area Figuration is less known.

Weeks had been a billboard sign painter. He became a colleague of theirs teaching at the San Francisco Art Institute. He had destroyed all his figurative work in 1957 and begun over.

Weeks frequented jazz clubs and boxing rings. He was not just painting his own world and I was surprised that more has not been written about this white man, who, like Alice Neel, was unafraid of depicting people of color--though they were more part of her immediate world.

There are geometries and brighter, even harsher colors than the others in the group utilized , but the focus is on the posed, almost stilted, photographic, Fighter and Manager, from 1960. Weeks is often singled out from the others for his 'plain style'. He did paint landscapes—as noted by his granddaughter. He had been strongly influenced by the Mexican muralists and imparted a layer of social concern to the movement, which to my eye, seems to bring us right up to the present.

The Sea Ranch at SF MoMA: If you build it, will they come?

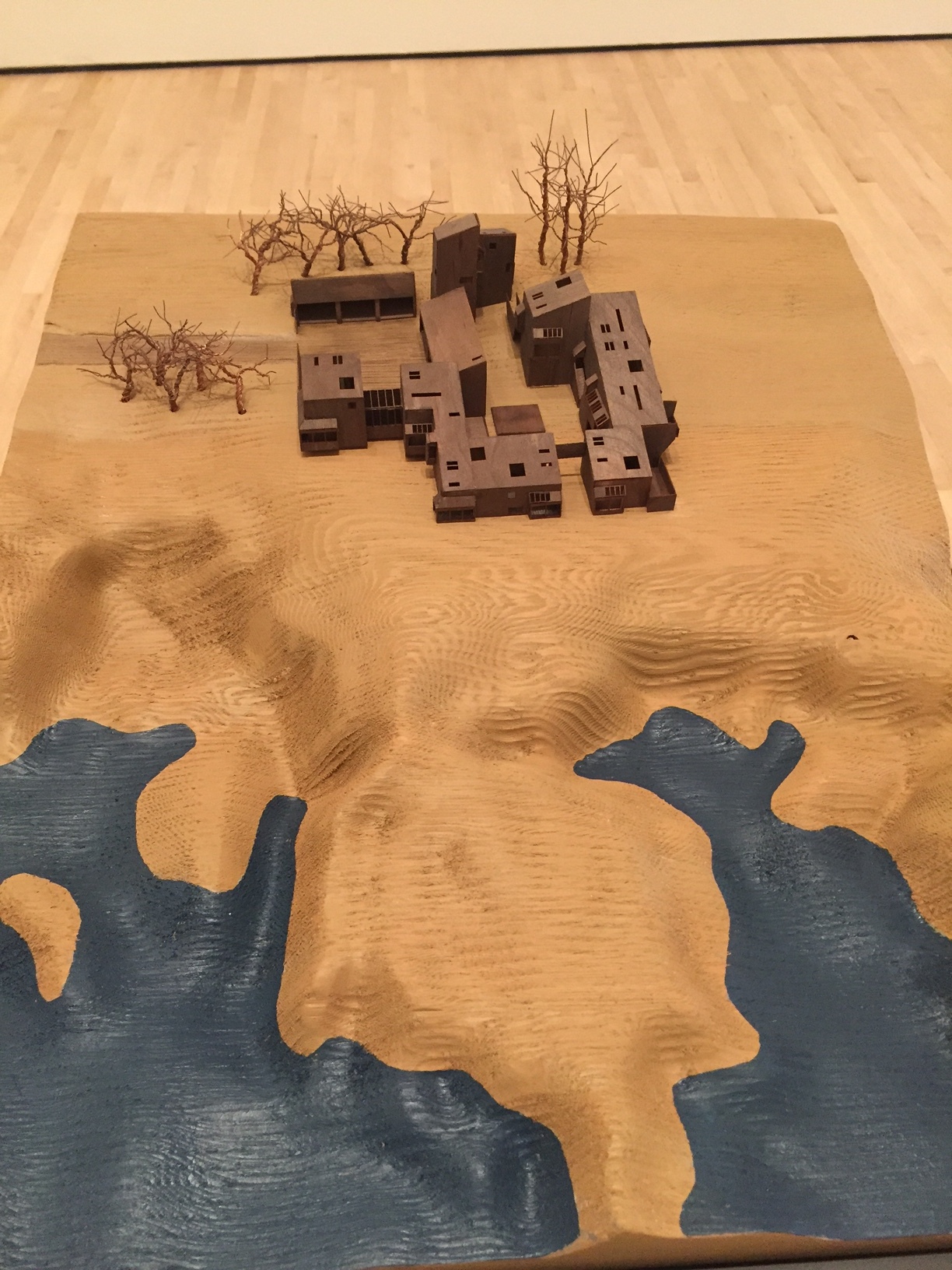

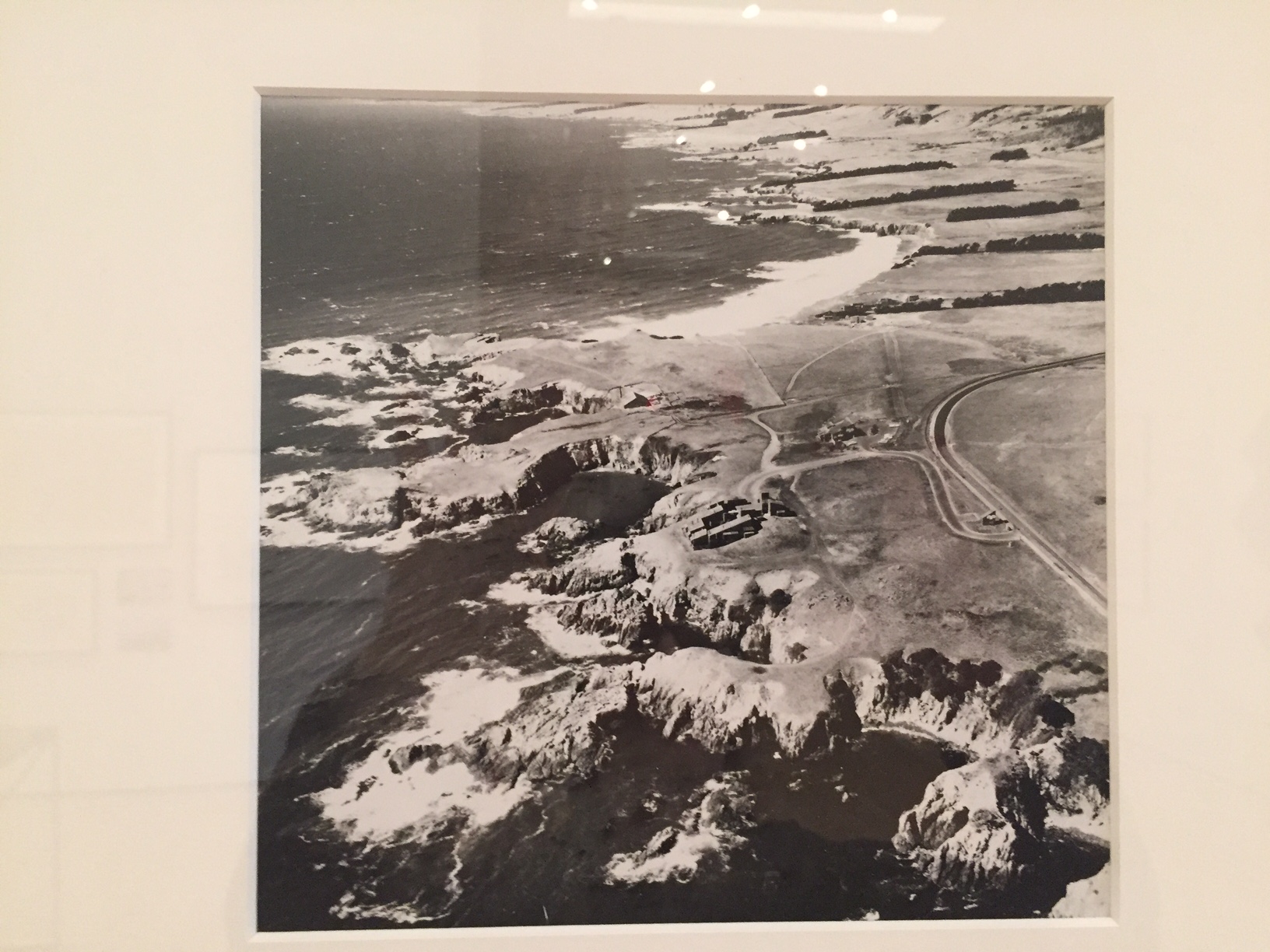

Sea Ranch, a sixties Utopian project by Bay Area architects and designers about 100 miles north of San Francisco, is now the subject of a tightly focussed exhibition at SF MoMA, and still exemplar of a remarkably sylvan development along ten miles of pristine California coastline.

The purchase of the land was organized by Al Boeke, an LA architect- developer in 1963 and was a hat trick that would never be allowed today as problems of public access to the ocean arose almost from the very outset. The powerful California Coastal Commission—which now regulates billionaires from getting their way in Malibu and other seaside communities— grew out of the divisive politics of getting the Sea Ranch underway.

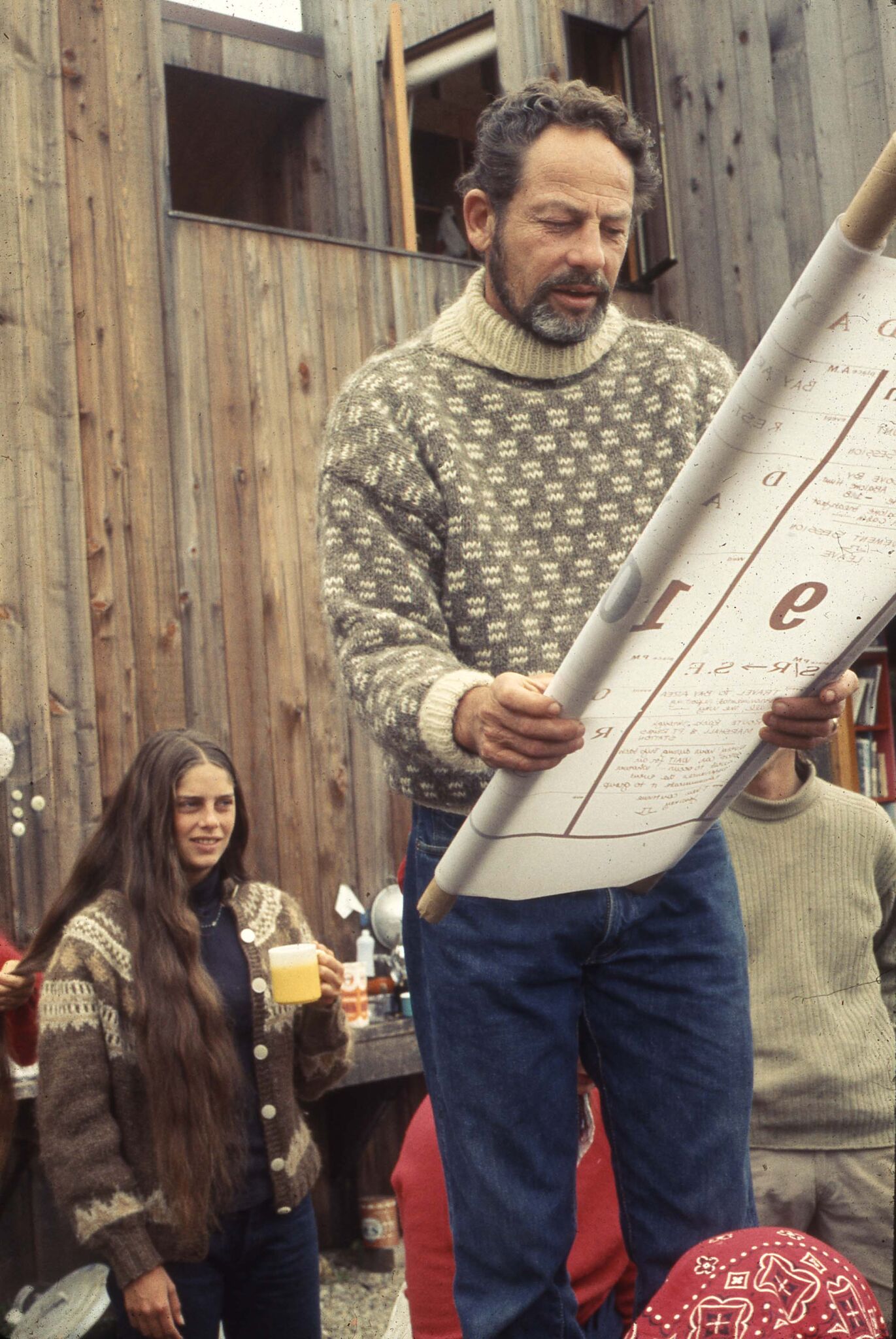

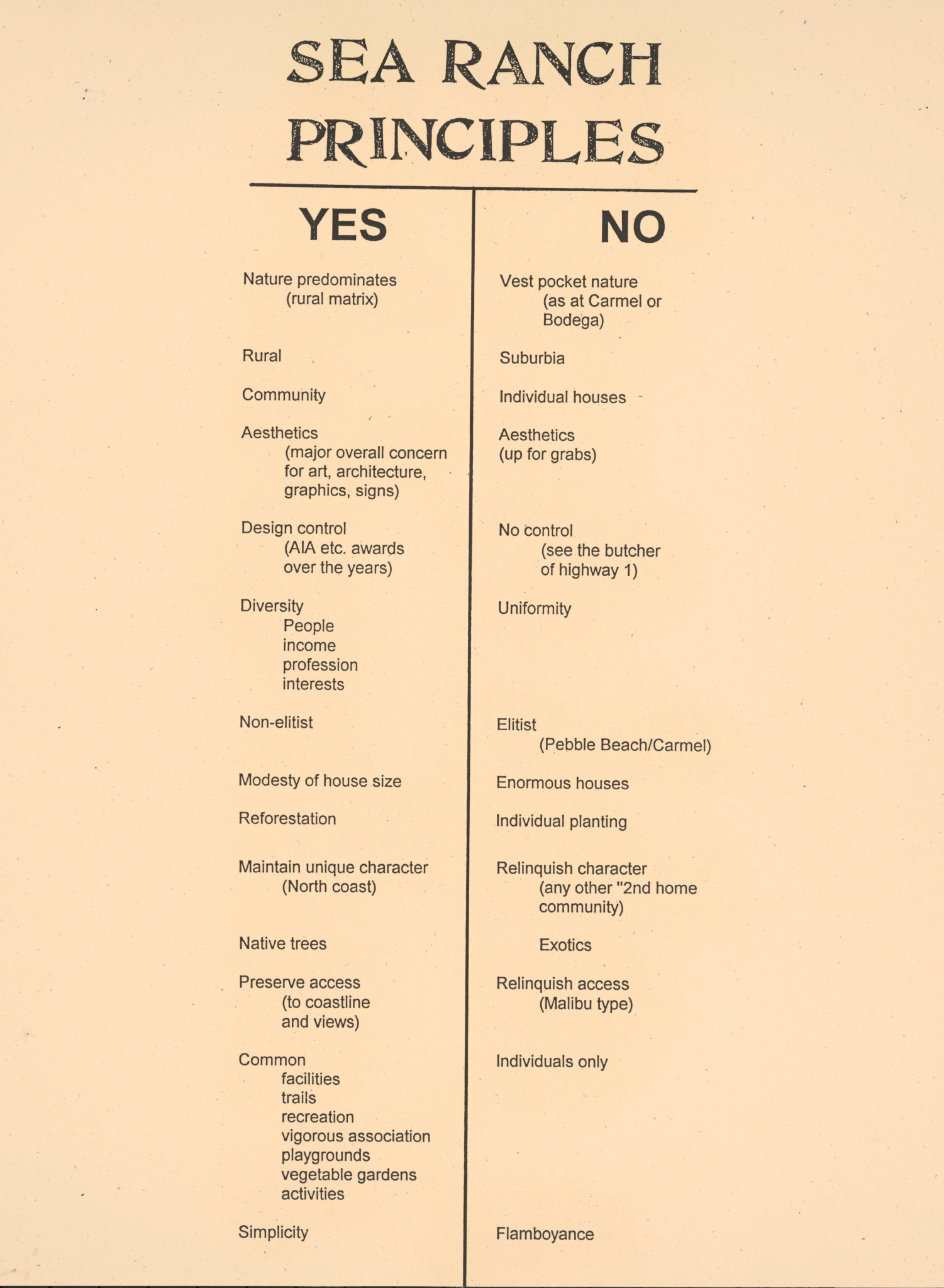

Larry Halprin, the opinionated landscape architect, was engaged to master plan the site and Joseph Esherick, Obie Bowman, Charles Moore, Bill Turnbull, and other architects and designers to create housing (the first condos) all out of unpainted redwood that would meld more naturally with the grassy, coastal landscape. Roofs had to have a specific slant. Bold graphic design and marketing by Barbara Solomon kept within the scheme. Originally, there was to be an escape from suburban style development, but when the concept didn’t sell well enough, more structures were added. Now there are over 1800 homes (many second homes or rental properties).

SF MoMA has built out the interior of a house within the exhibition gallery and it is under the weathered eaves you can catch a short film about the project with original participant interviews. As in Gibellina, Sicily, visionary but dogmatic planners were eager to influence the way we live our lives—see the list of dos and don’ts in my slide show (above). They were intent on making the development nature-and-environmentally friendly, yet ignored certain human foibles. The sixties and seventies were marked by this kind of futuristic ideation at a time when it felt like the world was indeed falling apart. Structure and planned community became a literal metaphor for trying to put back some kind of order into life.

The natural progression after seeing the show is the drive up to Sea Ranch where there are many vacation properties for rent and see what you think. Has it lived up to their prescription?

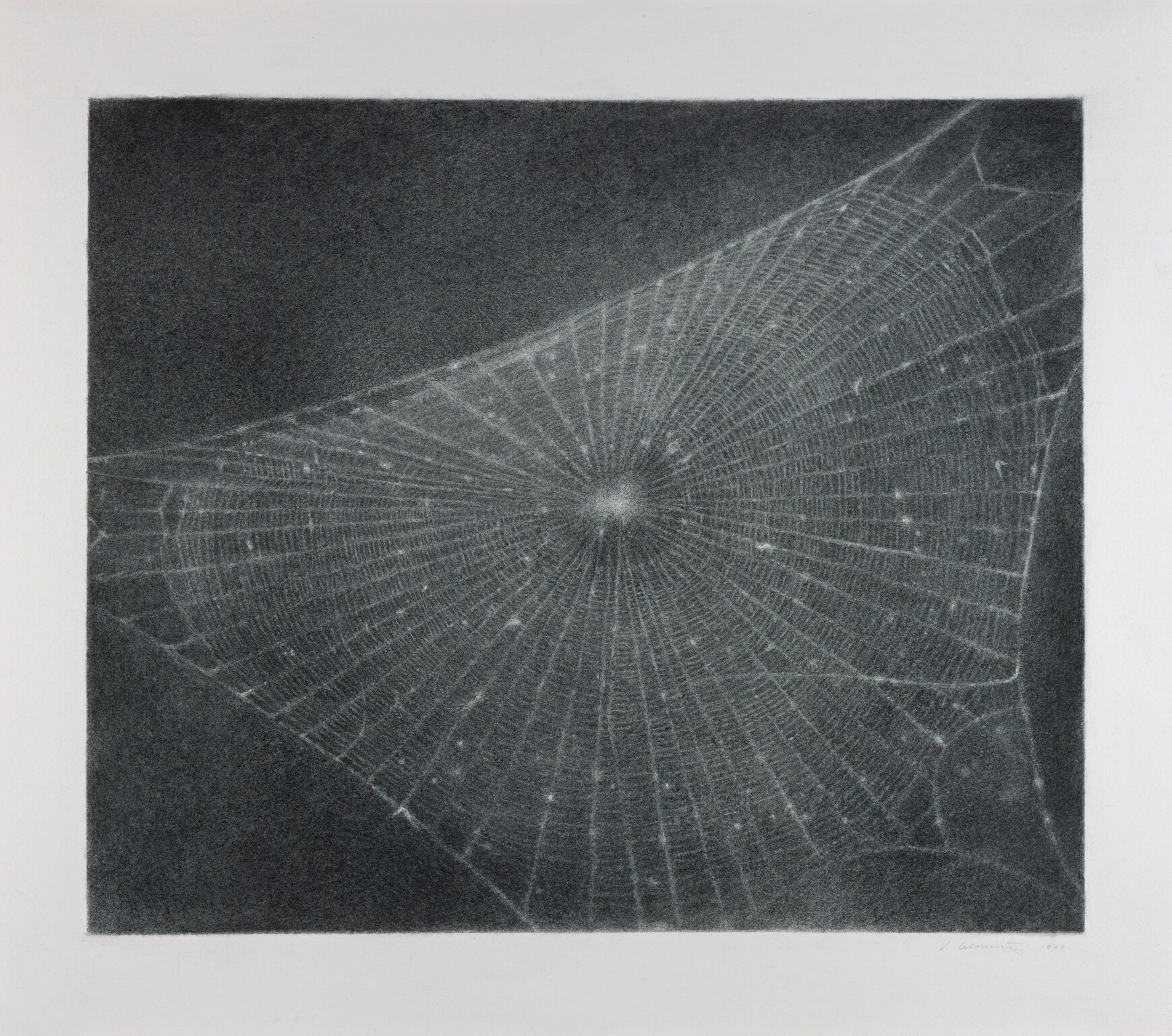

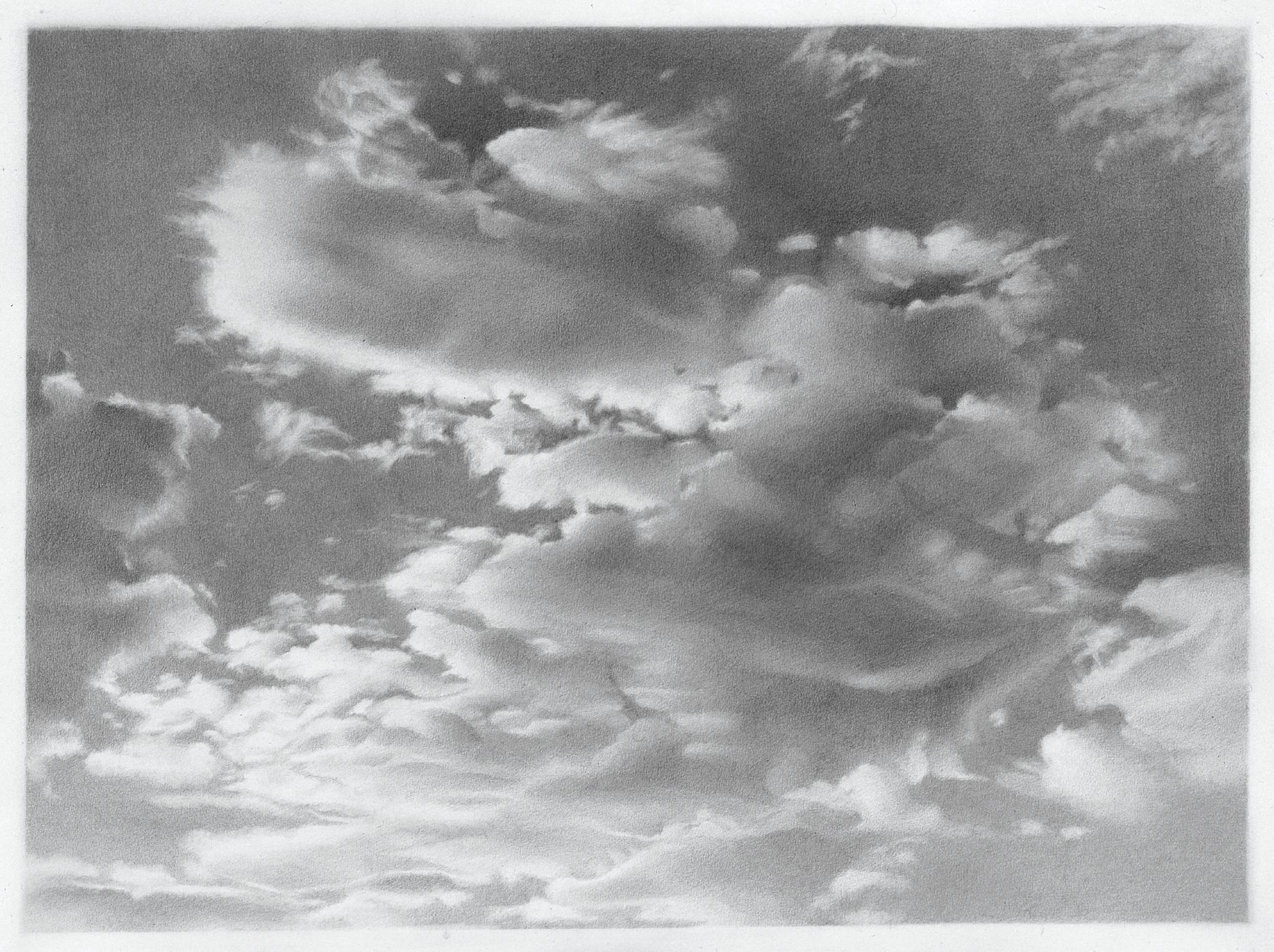

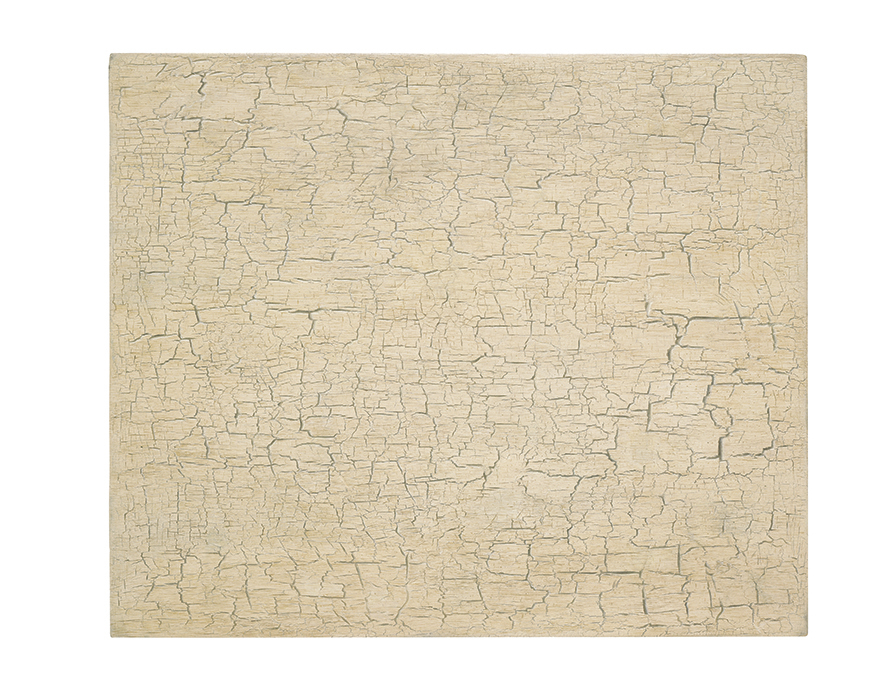

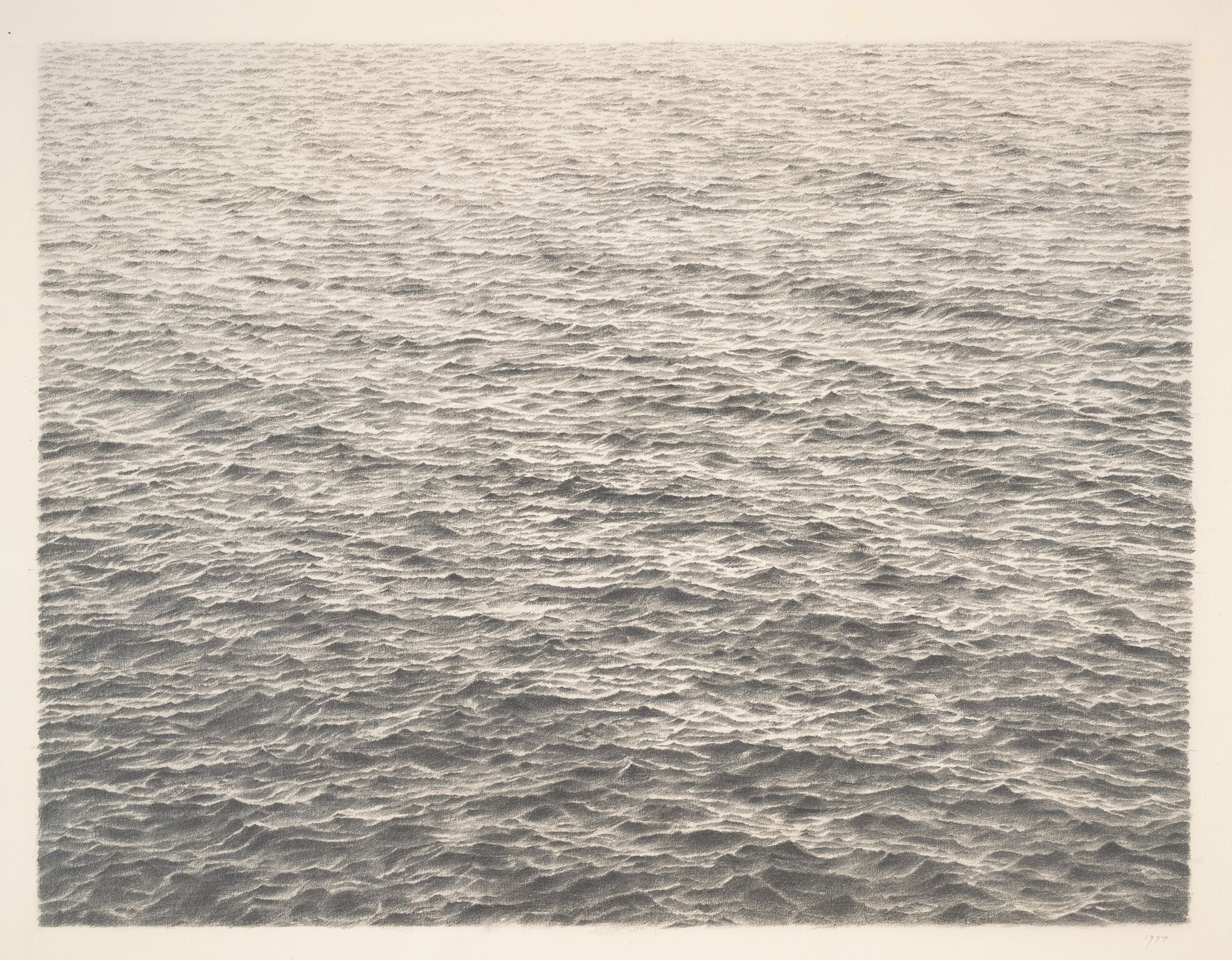

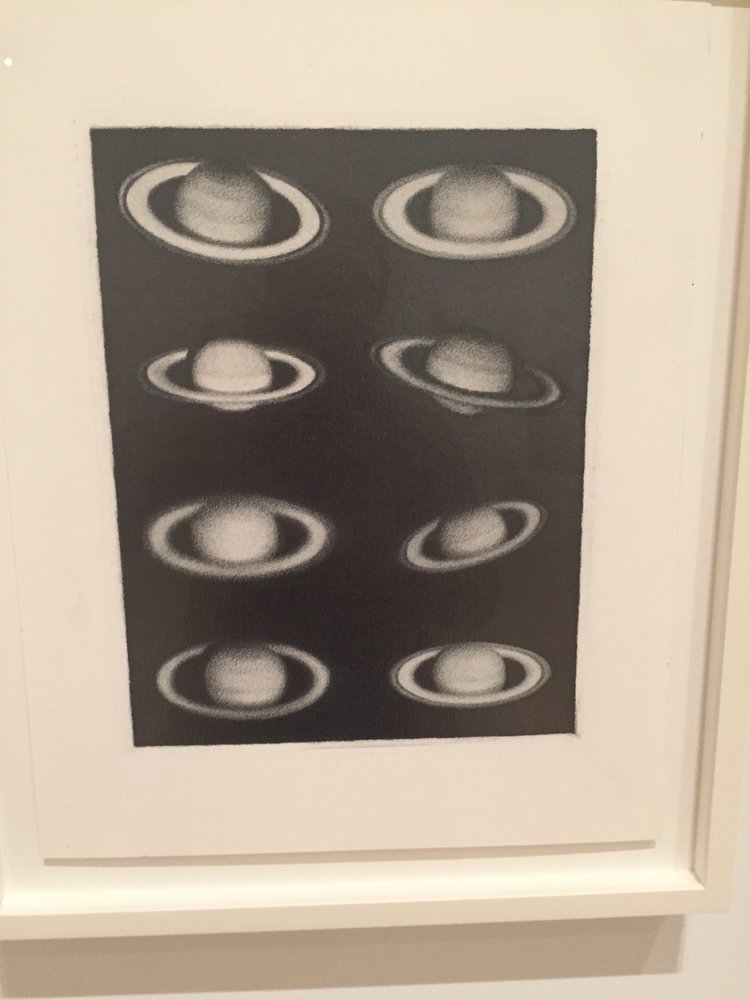

Vija Celmens at SFMOMA: To Fix the Image in Memory

The Vija Celmins exhbition curated by Gary Garrels at SF MoMA is very beautiful. Quiet, reflective, deep, it gives one the perfect January pause, a diet for the mind and spirit. Though born in Europe, California gave Celmins, who attended UCLA, some of her greatest subjects: ocean, sky and desert. Her rendering of a craggy, desert landscape with its rusticated ochre reminded me of the crags in the Burri Cretto in Sicily.

In her meticulous graphic renderings of ocean waves, stars, planets, spider webs and other natural objects, she worked lower right to upper left on a bridge to avoid smudging. She never erased! How wonderful it would be if we could all be so precise in our lives. Her early work in the sixties, both Magritte-an and Oldenburg-ean was a surprise to me, but showed a sense of humor that doesn’t necessarily appear in the mature work. She called this body of work “falling out of the picture plane”. A view of the LA freeway from inside a car is just about as close to Joan Didion as one could get in imagery, Tuesday Weld notwithstanding.

In paring her later art back to its essence, Celmins is not intending to be spiritual but rather locate the meaning in physicality of the natural things she studies so carefully according to Garrels. Celmins approaches her subjects the way writers often approach their work. Is it real, or is it my memory of it that is real? Memory imposes an extra layer. In Celmins case, it is all to our benefit.

Be sure to take a look at the videos on the SF MoMA website. Celmins, who now lives in NY, will be at SF MoMA for a talk on January 31.