William Kentridge is a polymath, an entrepreneur, a ringmaster, an historian, a singer, a writer, a visual artist, a designer, and so on. There is probably no challenge too great for this maestro of the visual and performing arts.

The Head and the Load, a production workshopped at his The Center for the Less Good Idea atelier in Johannesburg and at Mass MoCA, and performed already at the Tate and in Germany, arrives at the Drill Hall of the Park Avenue Armory already finely tuned. I’ve long had trouble with seeing productions try to successfully fill this vast space. But apparently if you build it they will come—and there is no one better than Kentridge to think big.

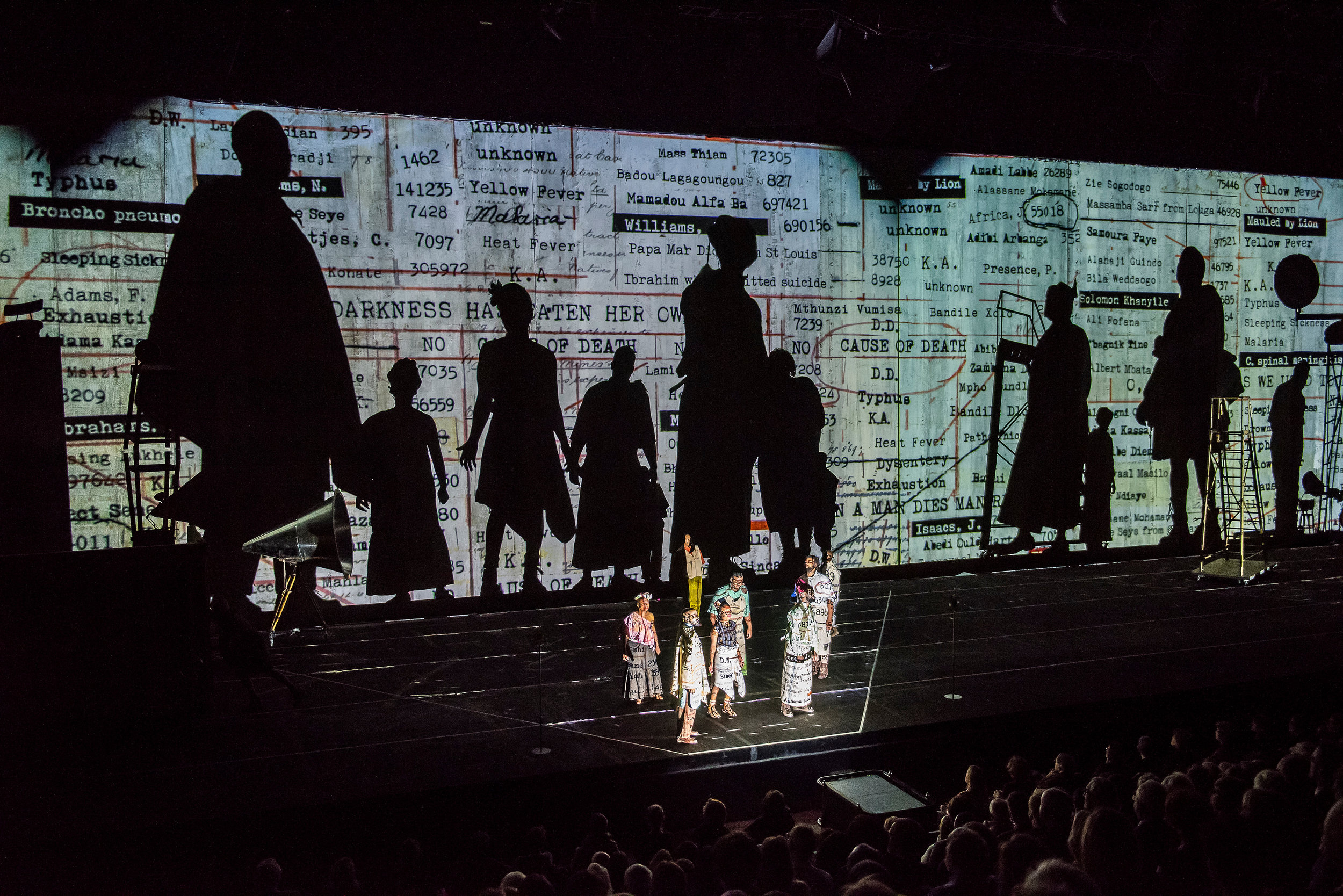

Taking as his ostensible subject the role of Africans in WW 1, Kentridge envisions a world where Africans are finally allowed to speak truth to power about what it was like to be a human vehicle (soldiers and porters) for troop strength and munitions during this global war in which Africa became part of the spoils. With his principal collaborators, composers Philip Miller and Thuthuka Sibisi, choreographer Gregory Maqoma, a local NY chamber orchestra The Knights and other accomplished dancers, singers, musicians and actors, Kentridge deploys some of his signature elements: live and video shadowplay, original documentation, animation, processionals et al) and delivers a vast and moving panoply of heartbreak and political strife.

In an artists talk before the performance, Kentridge described the gestation of the piece in an 8 day workshop in Joburg with 60 artists that gradually evolved over the course of other subsequent workshops. Some elements were also stimulated by his processional piece in Rome on the Tiber River. For The Head and the Load, Kentridge modified this processional approach with waystations: breaks for us to understand the deeper history and meanings of the conscription of native African troops into a far away war they barely understood.

English, French, German and African languages are deployed alongside voices in an arsenal of sounds that both emulate aspects of the destruction and elevate it. Having seen Kentridge perform the Schwitters Ursonate last year I heard the elements of Rakka Ta Bee Bee in the opening moments. Instruments are voices, voices are instruments, and as Kentridge says, he would be hard pressed to find opera singers who would challenge their vocal equipment quite so audaciously as these performers are willing to do.

Kentridge is recalling Dada and its emphasis on collage, on the spoken automatic word, on repetition as a tool for engagement. But the most affecting moment for me was the extraordinary pas de deux between two soldiers, one in a state of collapse, the other trying to haul him up and get him to salute. This is probably the most affecting new piece of choreography I have seen in a very long time, and is as moving and intricately plotted as any of the Swan Queen with her Prince. Kentridge says he wanted to emphasize the contrasting “tenderness and violence”

Kentridge resisted the temptation to focus on one character’s three act journey, a more conventional operatic approach. Instead this collage method (his default) allows him to graze on many stories which percolate, evaporate and then re-constitute as the evening progresses.

I still have trouble with the Drill Hall. My head moves in a kind of robotic 180 degree rotation, trying to capture the fullness of what the team is showing me. It’s not only tiring, I think it distracts from the pithiness, the anguish, the intensity.

But ok. Here’s a guy for whom the work size is irrelevant. He can work small (Ursonate) or large (The Nose), in museums, or in performing arts venues with equal aplomb. He is bravely opening a different window on non-western culture and history for all of us and is to be commended.

The Head and the Load continues at the Park Avenue Armory through December 15.