I always wanted a daughter and now with her newest novel Wayward, Dana Spiotta has shown me what that must truly be like. Her previous novels-Innocents and Others, Stone Arabia, Eat the Document and Lightning Field--had through lines around music, art, and film which brought them close to my experience. In Wayward she also hits another of my my sweet spots: architecture.

Spiotta has a way of rounding up the usual suspects and making them personal and new at the same time. Wayward, ostensibly the story of a woman facing mid-life and aging and getting lost along the way (who doesn't?), still manages to pull the rabbit out of the two stories, told by Sam (the mother) and Ally (the daughter).

Sam separates from her husband because she falls in love with an old house which becomes the vessel for her confusion and frustration with her marriage. She cherishes the tiles, the wood, the way the light comes in through the stained glass windows. Everything that is no longer cozy and even sensual in her marriage comes alive again in her cottage. The joy of finding the proverbial room of one’s own. That it's the wrong side of the tracks just like her marriage is only sinks in later when she's the witness to violence.

But she's also obsessed with her daughter, trying to parse her every move, watching her mature--she has a relationship with a much older man, a friend of her fathers-afraid for her, paralleling her own maturation which is heading instead towards infertility, not new life.

Sam tries to rebound off the Trump election. She fine tunes her body as she is rehabbing her house. She investigates its history, searching for clues about how another woman made a life. She even made me feel affection for Syracuse, a city for which I thought I could never feel anything positive.

I interviewed Spiotta in 2016 and was able to post some images of her about Ally's age. Take a look.

Mary McCarthy orphaned during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic

When lit star Mary McCarthy, future author of the incendiary The Group, about her post-Vassar years, was six years old, her uncle, the family's success story, left for Seattle in 1918 to oversee their move to Minneapolis after the onset of the Spanish flu pandemic. Her mother, brother, future actor Kevin and the two other siblings and her father were likely already sick. Instead of sheltering in place, they evacuated first to her grandmother's house since no hospital beds were available, then to a hotel. They boarded the train and one by one were carried off, ill or near death in the case of her parents. McCarthy became an 'orphan', and she recounted this defining experience in her Memories of a Catholic Girlhood, one of the first and best memoirs in which she doubts her own memory. It's something to read now when all of our memories will surely be compromised by this insidious, stealth Covid 19 disease. What is the truth?

Afternoon of a Faun: James Lasdun writes MeToo as a Thriller

Spurred on by a review by Katy Waldman, I read James Lasdun’s slender but riveting novel Afternoon of a Faun. It was probably the frisson of the title drawing me in at first (Jerome Robbins ballet drawn from the same source is a particular favorite) but Lasdun has managed the hat trick of both taking a story ripped from the headlines and crafting a thriller around it. An unreliable protagonist, an unreliable narrator and an unreliable subject and #MeToo combine for some page-turning narrative delights and I could not put this down. It felt so good to be engaged in a novel, I am finding it a challenge to lose myself in fiction these days as it cuts so close to the bone. Highly recommended.

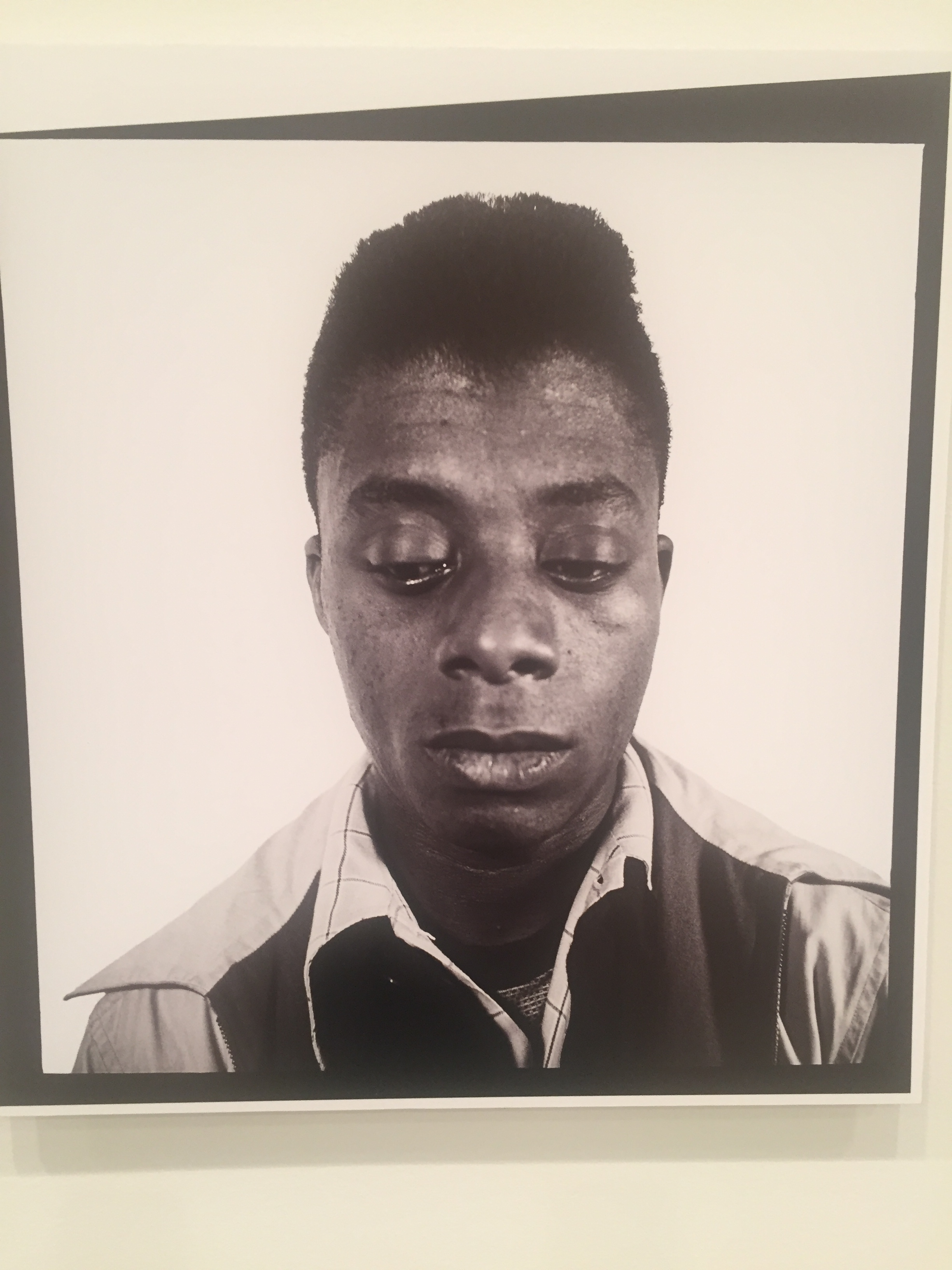

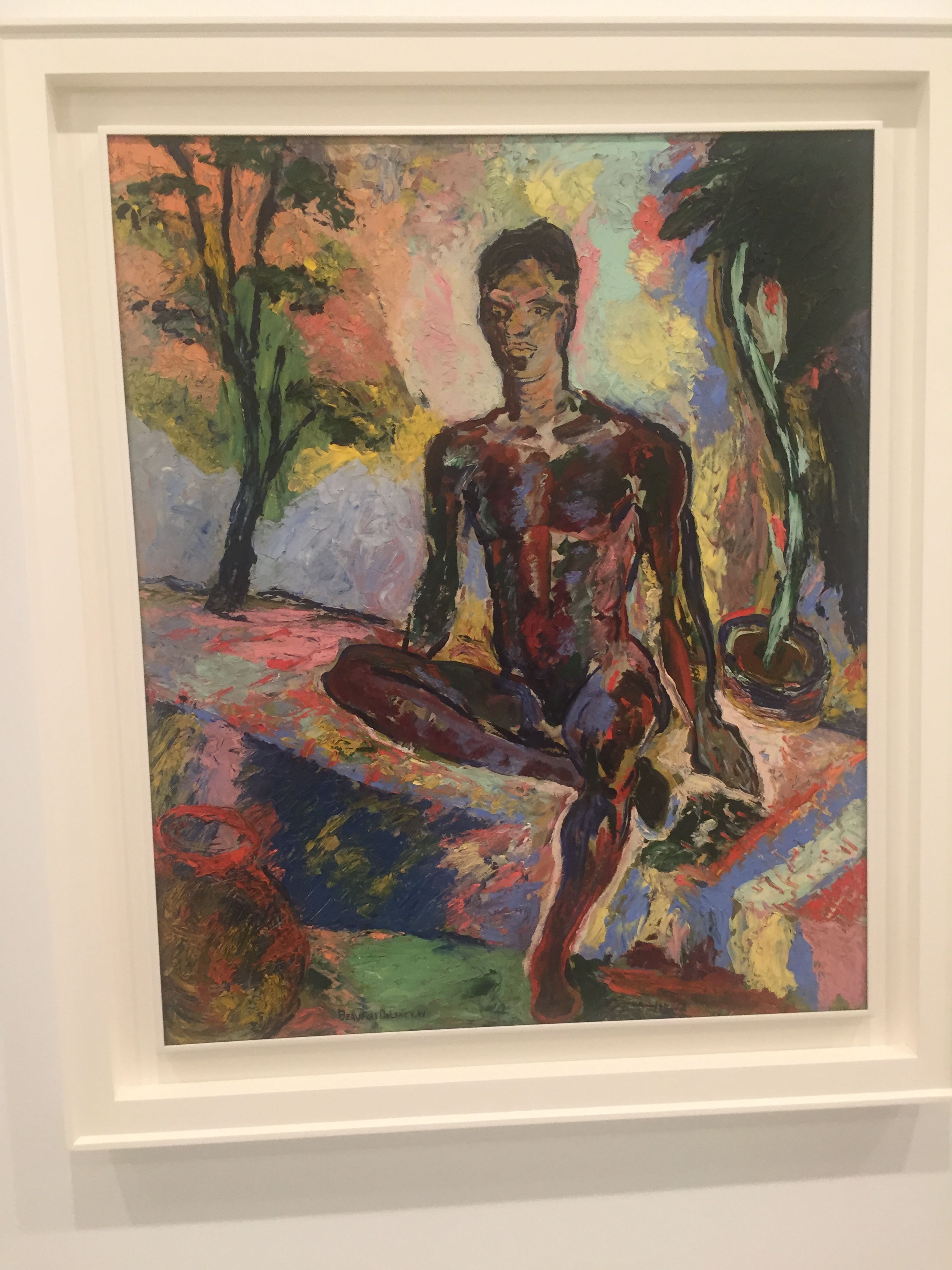

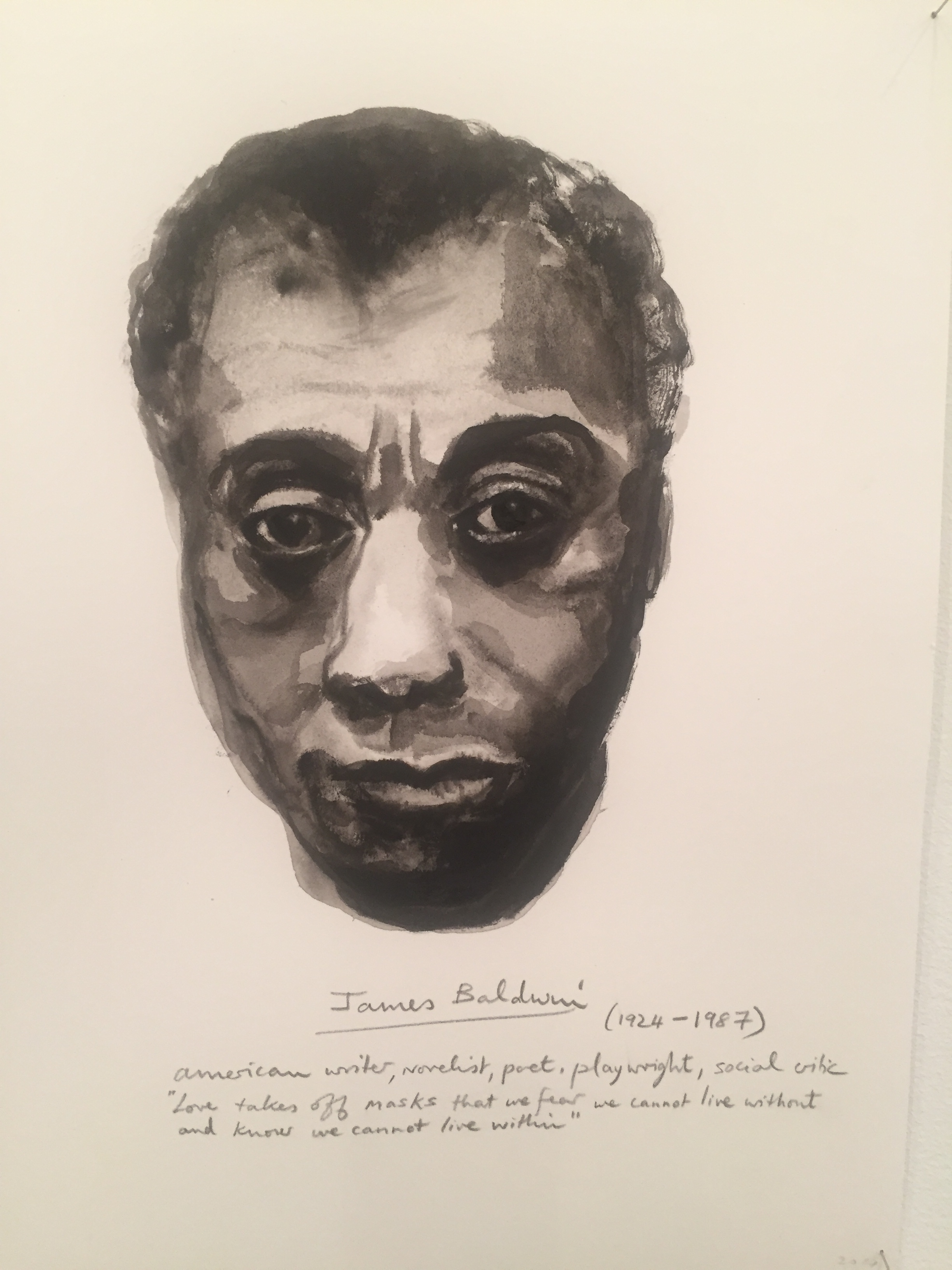

God Made My Face: James Baldwin via Hilton Als at David Zwirner

“I remembered myself as a very small boy, already so bitter about the pledge of allegiance I could scarcely bring myself to say it…I was in short, but one generation removed from the south.”

So opens the moving exhibition on James Baldwin, God Made My Face, curated by Hilton Als at David Zwirner. In two distinct sections, A Walker in the City and Colonialism, Als offers us original text and images as well as commentary by fellow artists.

“He will not be swiftly forgiven for having turned so many tables,” Baldwin writes of Michael Jackson. The same could have applied to Baldwin himself.

Baldwin had a fraught childhood: his mother fled from his real father and traveled north. His stepfather, a preacher, had 8 children with his mother and especially disfavored Baldwin. After trying to be comfortable in his own skin in Harlem, he escaped to Paris. As for so many of us, Paris was both the tonic and the siren we thought would let us be who we really were. You didn’t have to be black and homosexual to want to have the artistic freedom of Paris. His friends became his family.

Baldwin had a slow but steady emergence from his painful chrysalis as a profound writer (original editions of the books are on display ). But he also kept a close eye on other forms of culture: film, theater, music, photography. His friendship with Richard Avedon began at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx (my father also attended) and they stayed close.

He was especially keen on filmmaking, but that did not work out as well as he had hoped. His métier instead was to dissect himself, his culture, the people and circumstances who had discouraged and pigeonholed him including his own family.

After publication of The Fire Next Timein 1963, Baldwin emerged as a leading cultural figure, one with agency. He then had more courage to take on battles larger than his own personal demons, ones that had long preoccupied him: the complicated legacy of civil rights, colonialism and its aftermath, miscengenation.

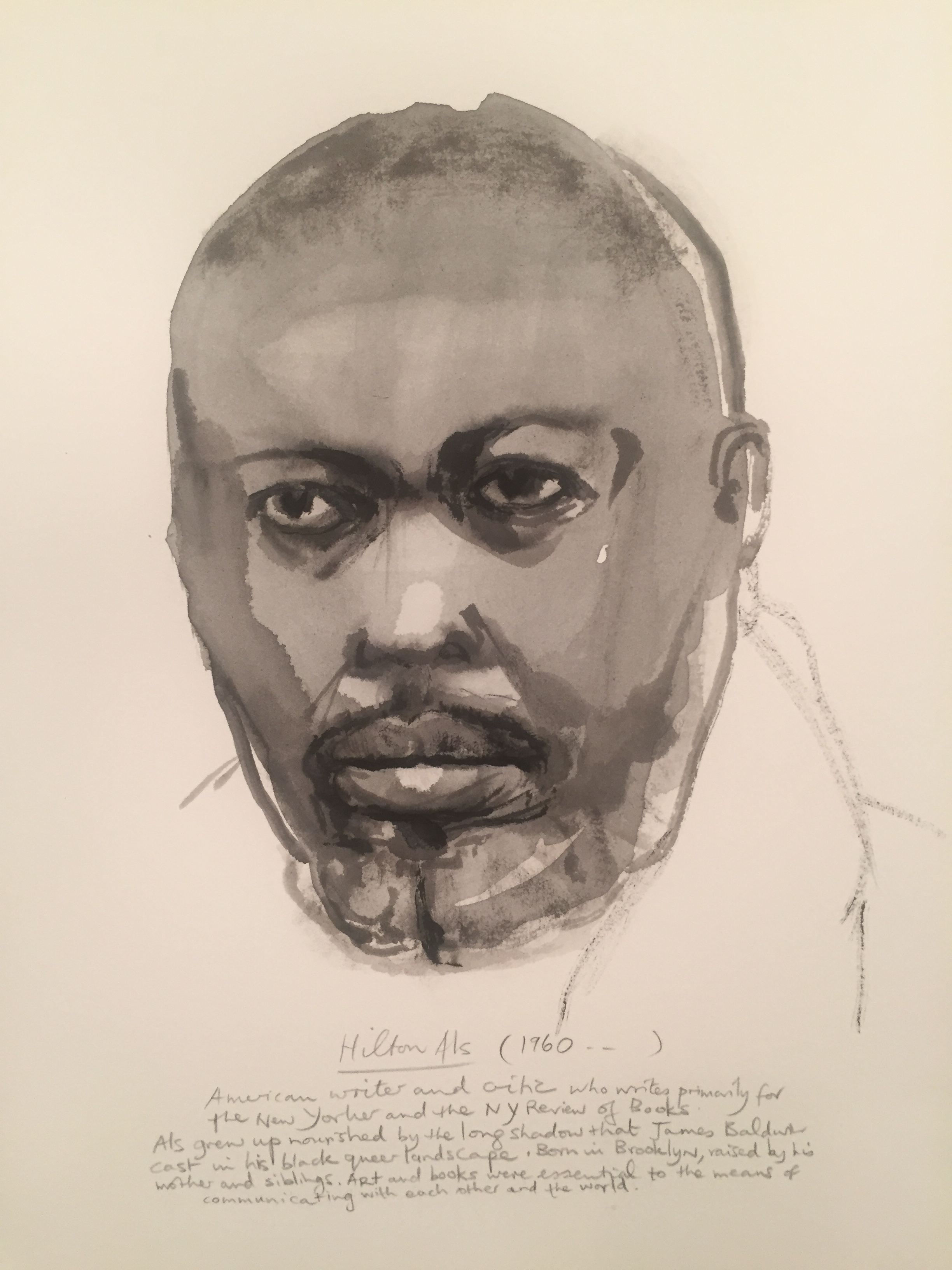

The topic of homosexuality was more challenging. Here at Zwirner, Glenn Ligon and John Edmonds weigh in on his behalf. Kara Walker, represented by her graphic film 8 Possible Beginnings,has never been abashed about telling it like it is. Marlene Dumas’s black and white watercolor series of writers and artists she periodically adds to imports a very personal dimension to some of Baldwin’s friends and contemporaries.

Curator Hilton Als himself seems to have picked up where Baldwin left off. Both as an excellent excavator of historical black culture (his last exhibition on Alice Neel also at Zwirner, was one of my favorites) and a supporter of contemporary black culture he excels. Yet he is a fluent about white culture as anyone.

With the film If Beale Street Could Talk and this exhibition, Baldwin re enters the culture for another generation.

Becoming Astrid: a film about the real-life Pippi Longstocking

My office library is organized by subject matter. Non fiction—biography and memoir—load most of the shelves. Fiction is in the bedroom—hardcover—and art books in the den. The children’s books are still in one of the rooms once occupied by my youngest son.

But on the two shelves above my desk are the books which are the most personal. The series of French film books and DVDs of the New Wave, the books by friends which have been inscribed to me by their authors, and a short selection of novels and non fiction which reference my current work.

On the very top shelf, in the middle, now encased in a plastic baggie as it’s so fragile is the paperback version of Pippi Longstocking which I ordered as part of the Scholastic book club in elementary school. The binding is shot, the pages are brittle and many are loose and have disengaged from their mooring.

I know I am far from the only girl, or person, who nourishes such fond affection for a novel which found in me the brave girl I wanted to be, who didn’t give a fig for what anyone else thought, who could climb trees and wash the floor as if she were skating, had a horse in her backyard and was so strong she could lift him, who made excellent pancakes, who could sleep whenever and however she liked, join the circus, and had a pet monkey and was so nice to the more conventional children next door.

Author Astrid Lindgren found her way to millions of childrens’ hearts all over the world because, as one says in a letter she receives when she is very old in a new film biography from Sweden, “ You understand us Astrid, you are on our side”.

Becoming Astrid directed by Pernille Fischer Christensen tells the fairly conventional story of an unconventional girl: a rebellious farmgirl with talent who leaves her family behind as her talent is recognized, and along the way has a affair which changes the course of her life, but only serves to deepen her ability to understand how a child feels.

And it shows in a very simple way how it’s impossible to entirely separate the writer from the document no matter how much they (we) protest.

Like Laura Ingalls Wilder, Lindgren took the basics of her own life and put them into her stories; she wrote many more books but Pippi is the one best known to English speaking audiences.

I don’t really want to spoil the film for anyone. Alas I believe one sex scene would make it difficult for anyone younger than middle school or high school to see it, it’s really a film for older teenagers and adults.

I took an informal survey of friends. Everyone identified with Pippi. Like Eloise and Madeline she is smart but feisty, all three of them girls who prevail in the end just by being themselves.

The film is perfect holiday treat about loss and forgiveness, following your passion, the clichés of growing up and out which are all too true. A new generation is discovering the marvels of Pippi every day.

It opens on November 23rd.

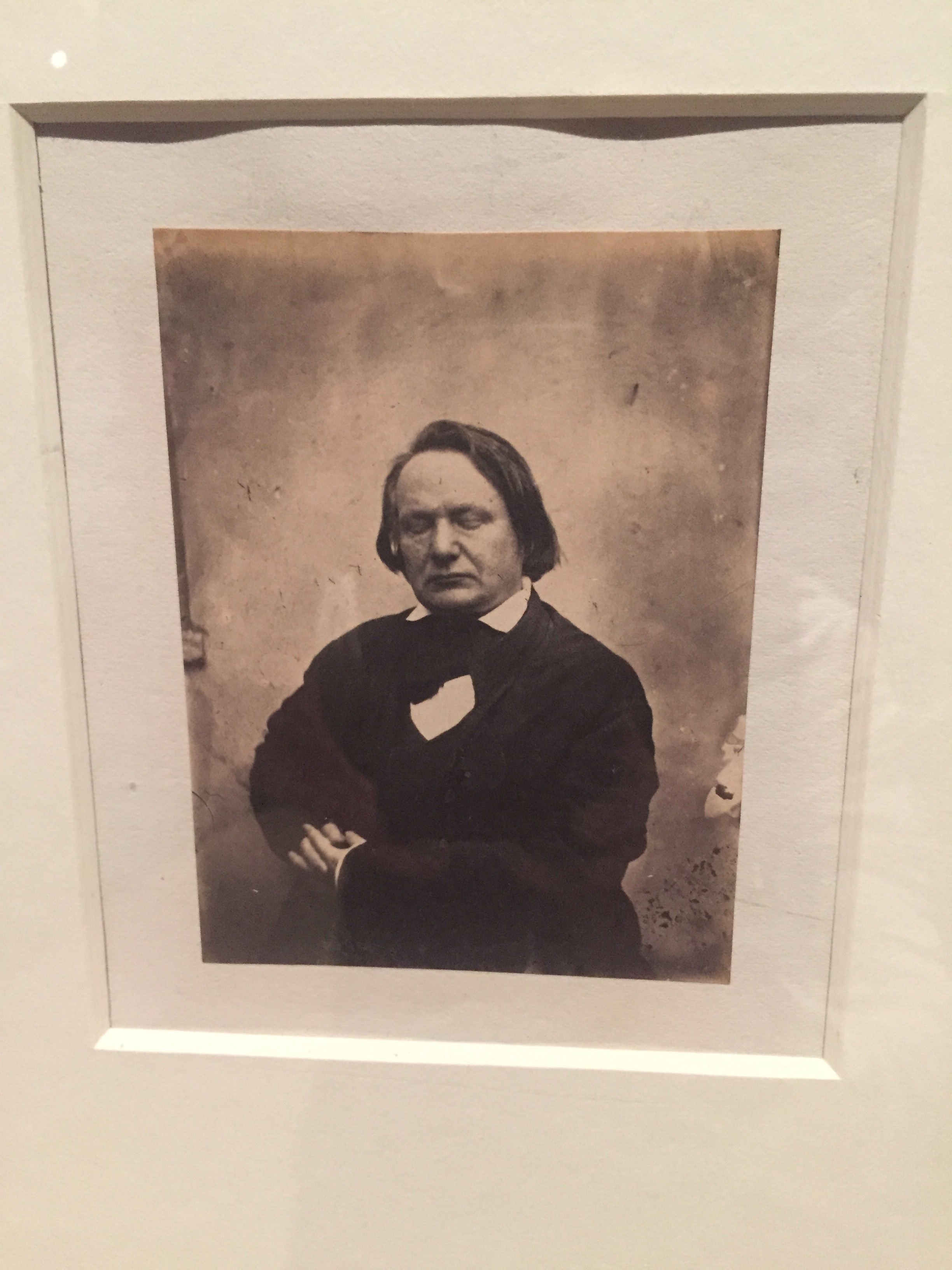

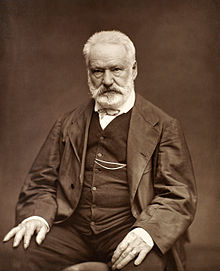

Stones to Stains: Victor Hugo's romantic drawings at the Hammer Museum

As a college student of 19th Century French literature, I became enamored of the great observers of love and life, Baudelaire, Flaubert, Zola and Balzac. Though Victor Hugo, poet, journalist, statesman, politician and hero of the Republic for his resistance to waves of Napoleonic repression and the death penalty was among them, it was not until I saw Francois Truffaut’s L’Histoire d’Adele H while working at the New York Film Festival that Hugo resounded for me in a more personal way.

The story of the film is based on the true story of Hugo’s daughter Adele, diagnosed in real life with schizoprenia, but in the film primarily the victim of unrequited love. As anyone who has seen the film knows, Adele goes crazy after being rejected by a handsome solider with whom she’s had an affair, follows him to Halifax, then Barbados where she eventually collapses in the street and is returned to Paris and her father. Hugo never appears in the film as Truffaut, who got the rights from his son Jean, was contractually obliged never to depict him on screen. We hear him only in voice over.

In another stroke of luck, I was often able to stay at the home of friends on the Place des Vosges, right near Victor Hugo’s home which has been preserved qua home and archive.

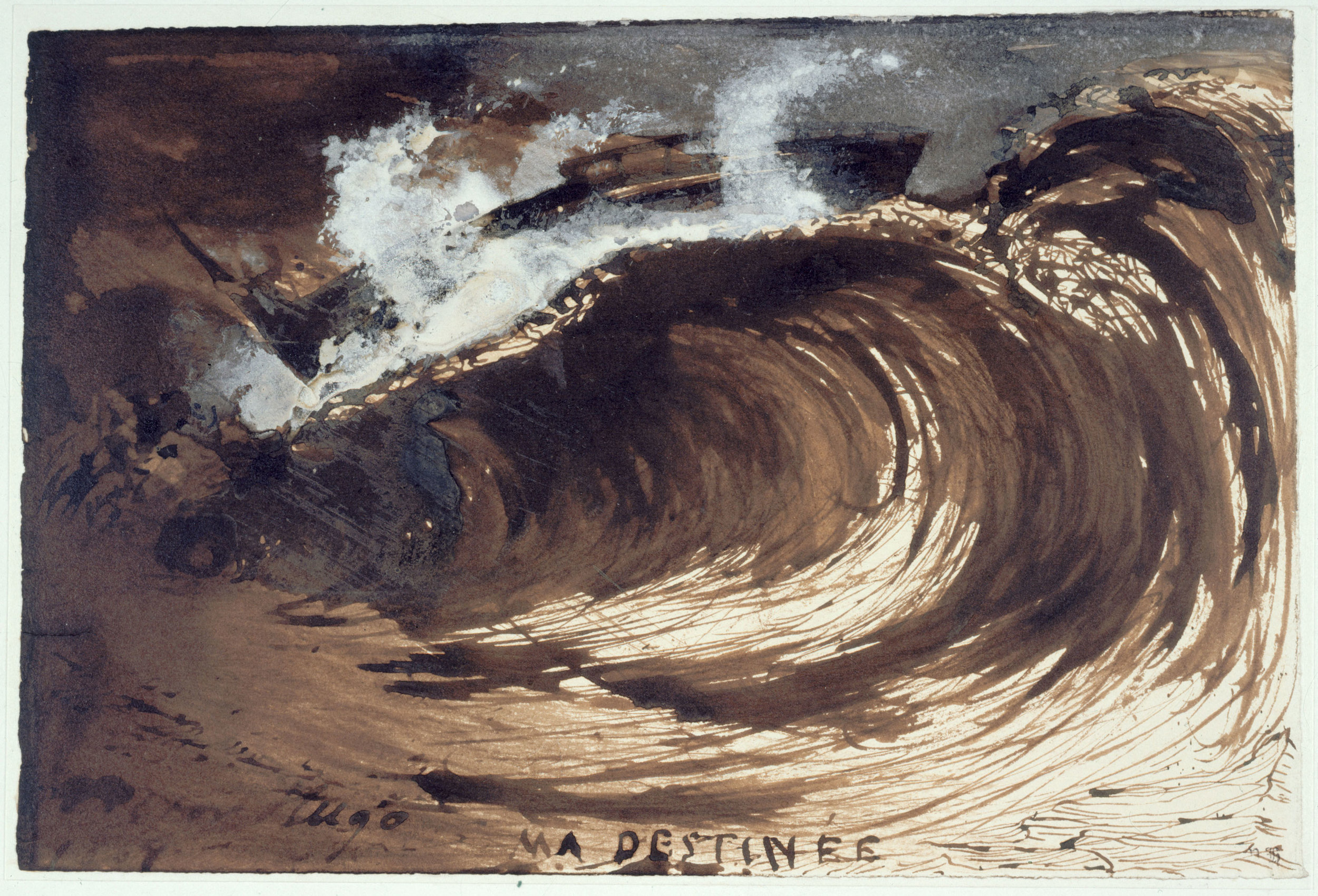

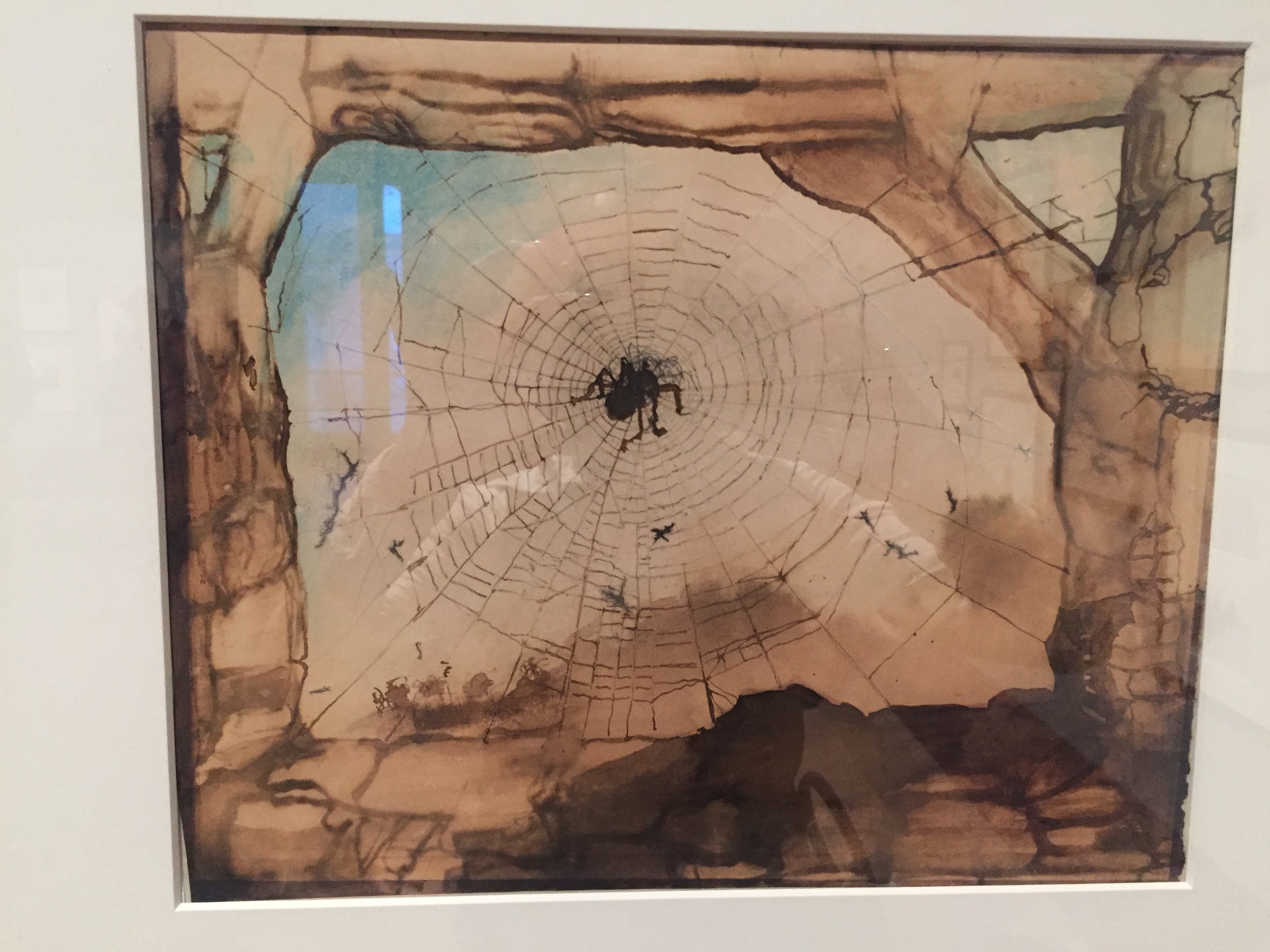

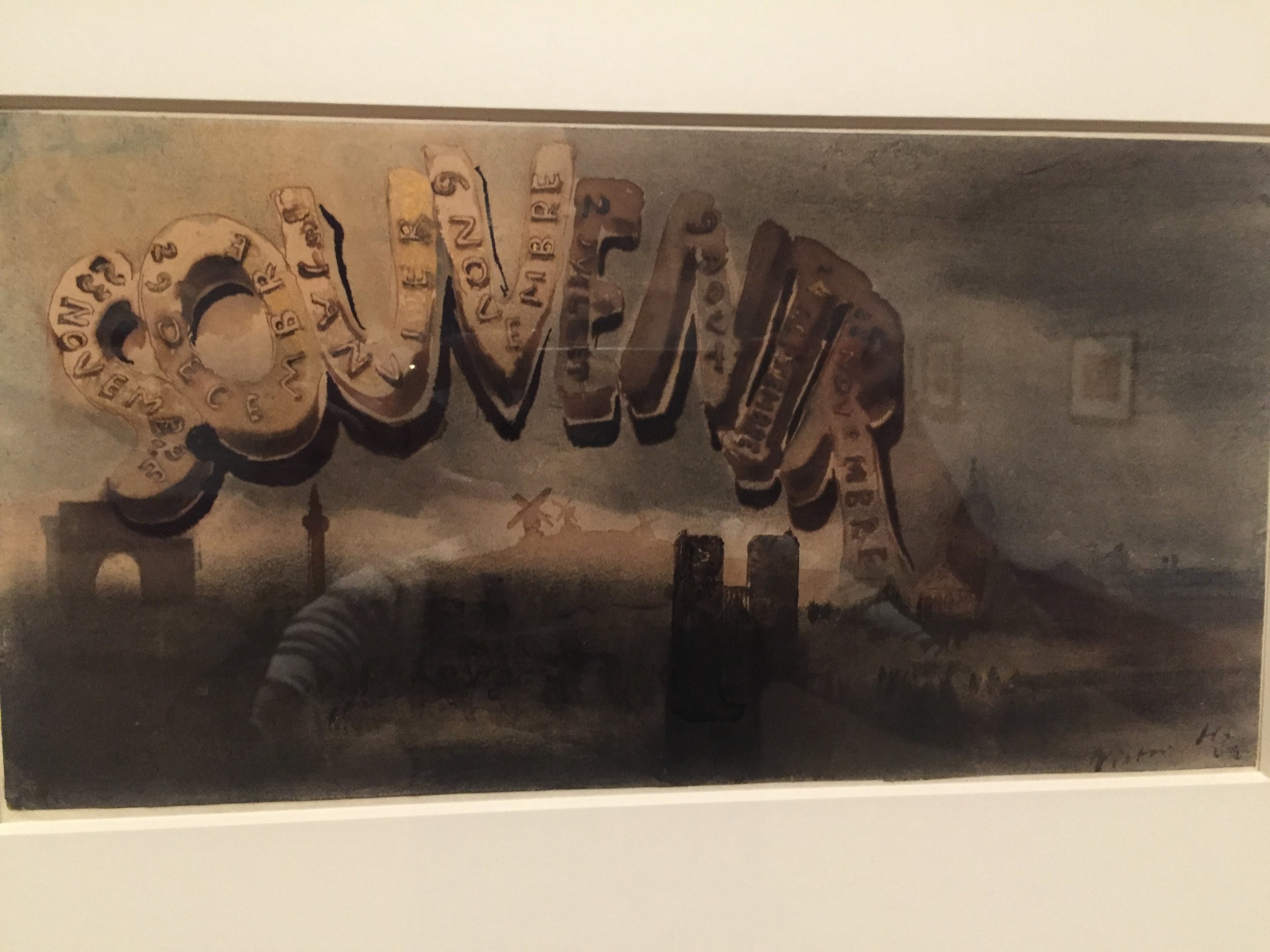

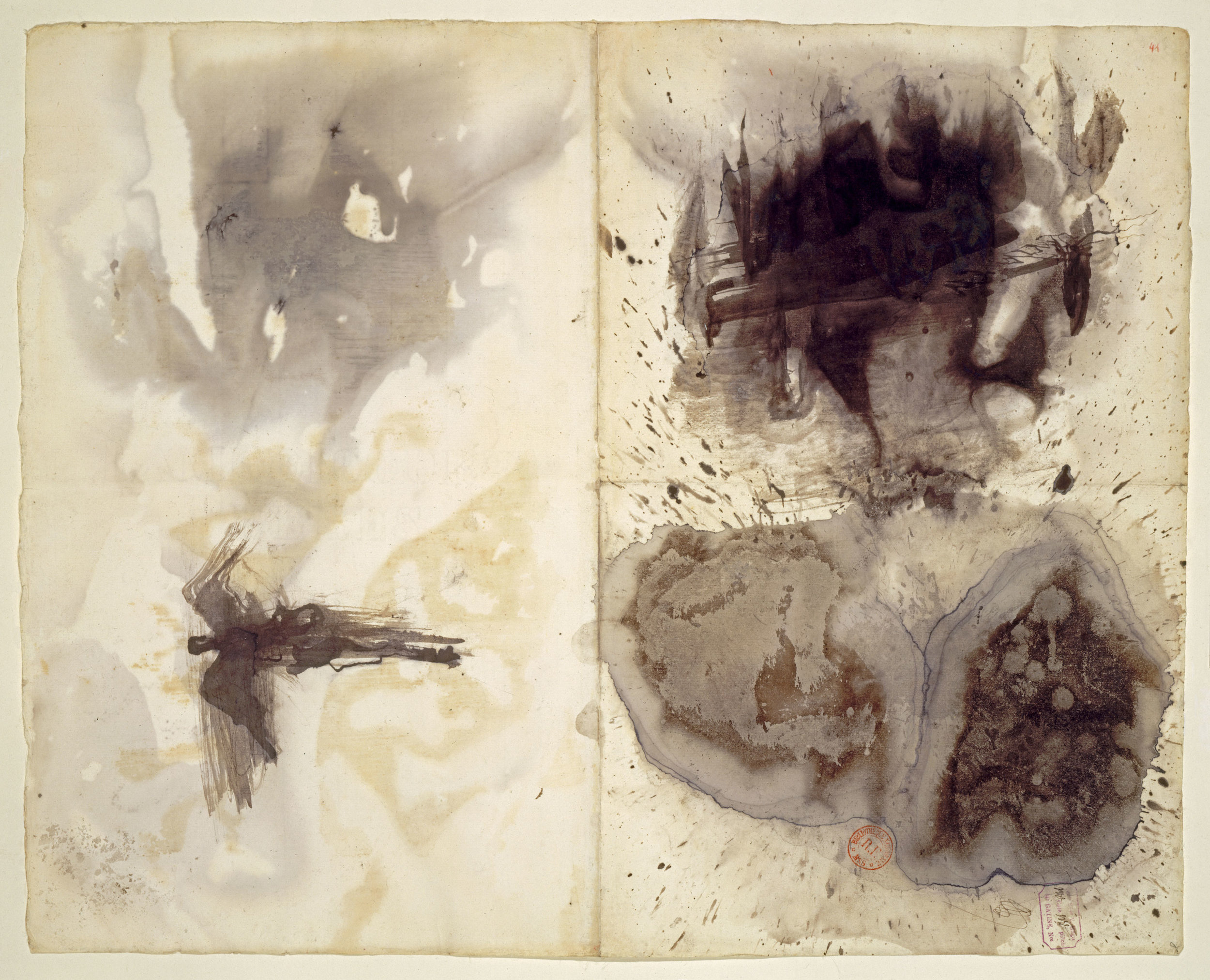

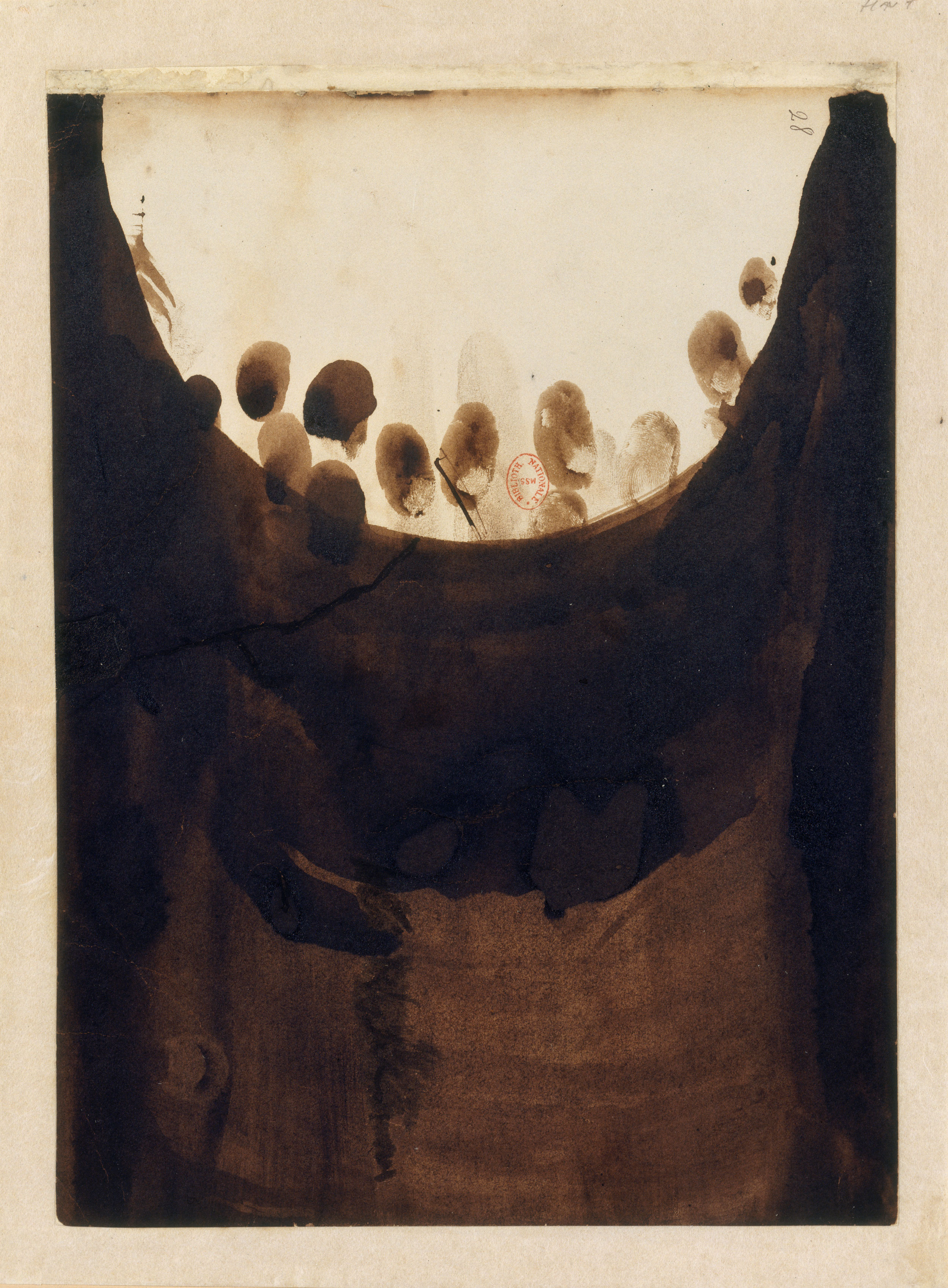

All this came back to me when I entered the magical exhibition of Victor Hugo’s drawings at the Hammer Museum curated by Allegra Pesenti and Cynthia Burlingame. Besides being one of the leading writers, politicians and human rights advocates of his century, Hugo was a marvelous and ingenious draftsman and observed and depicted the world in a very original way.

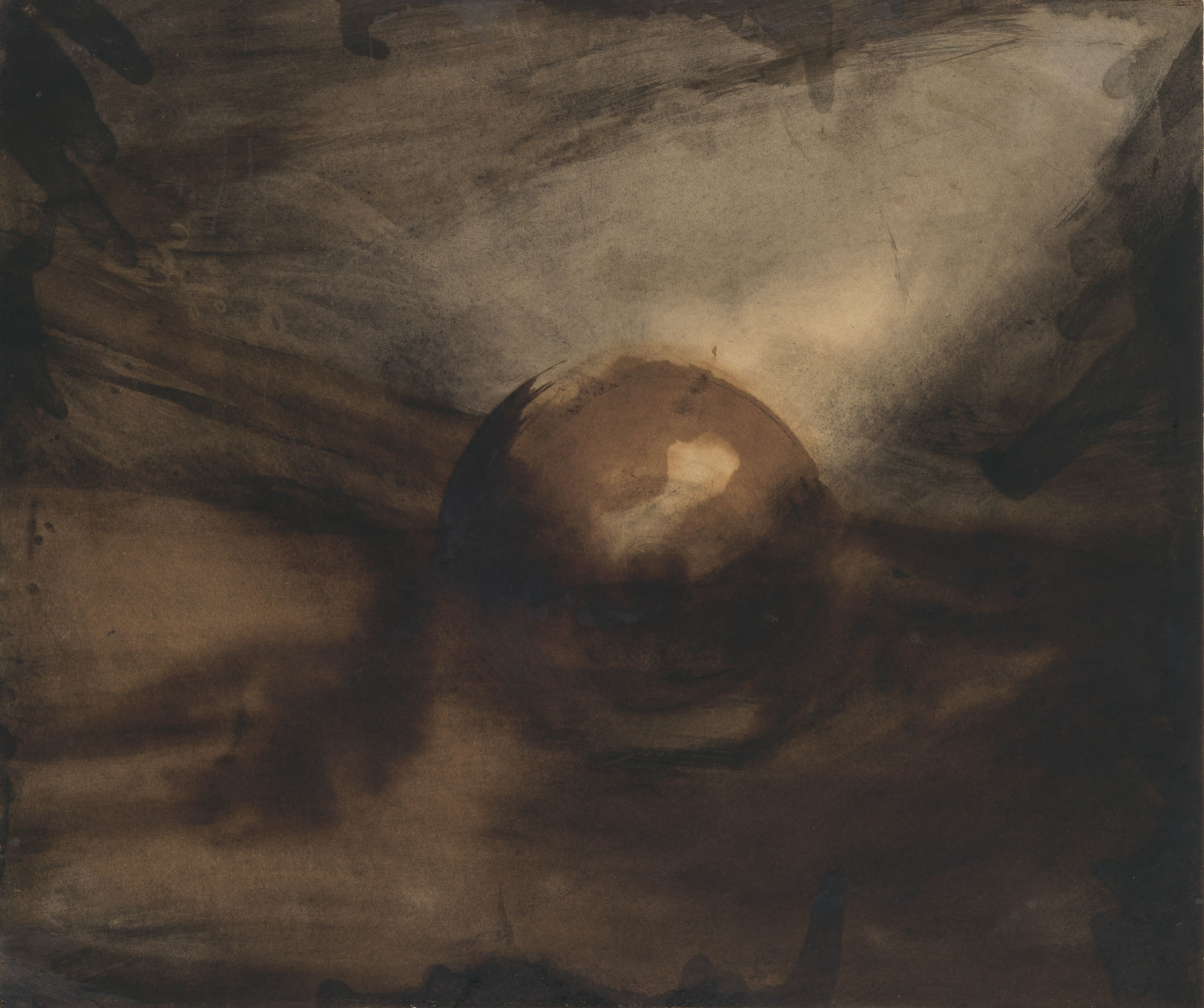

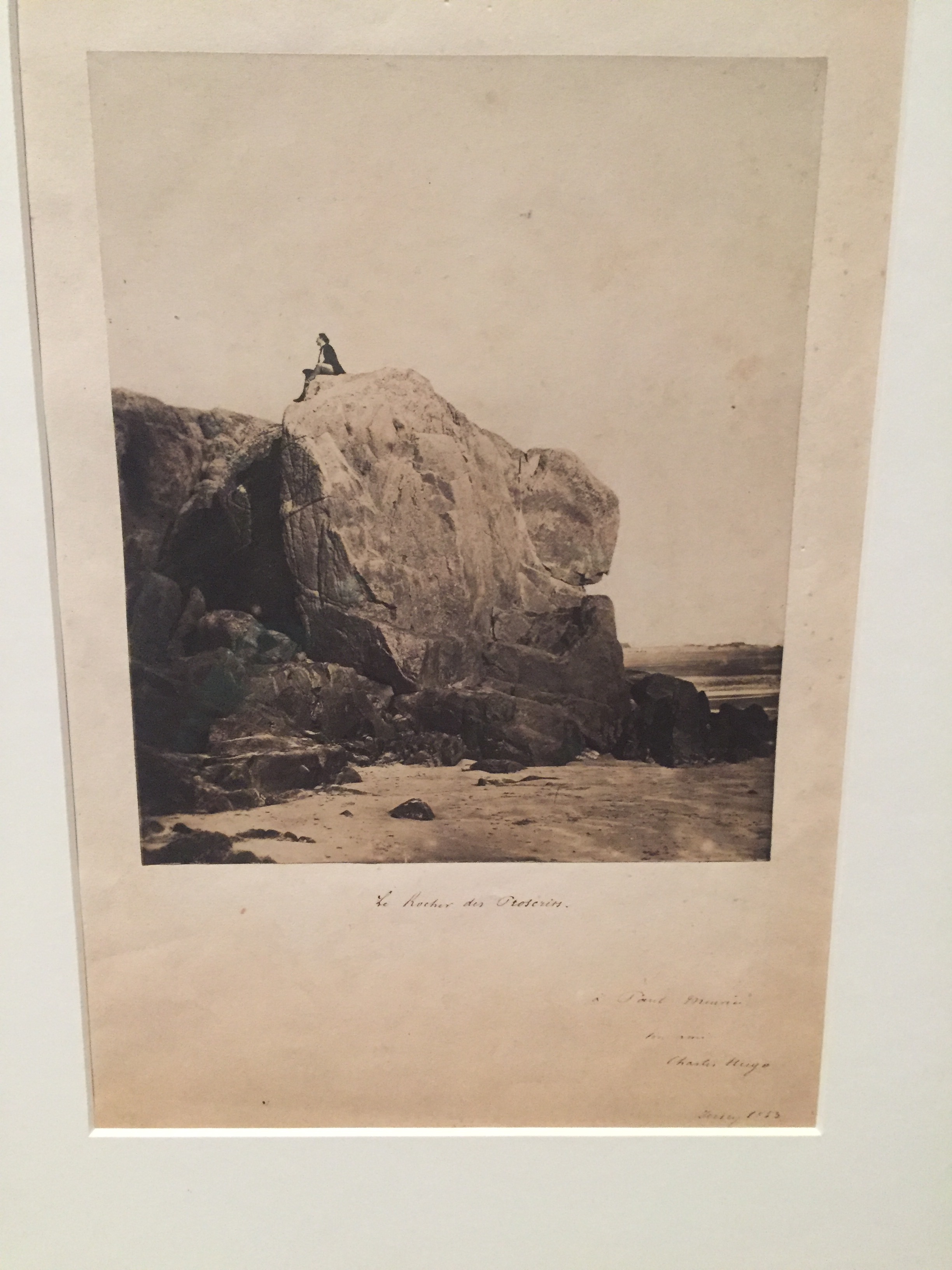

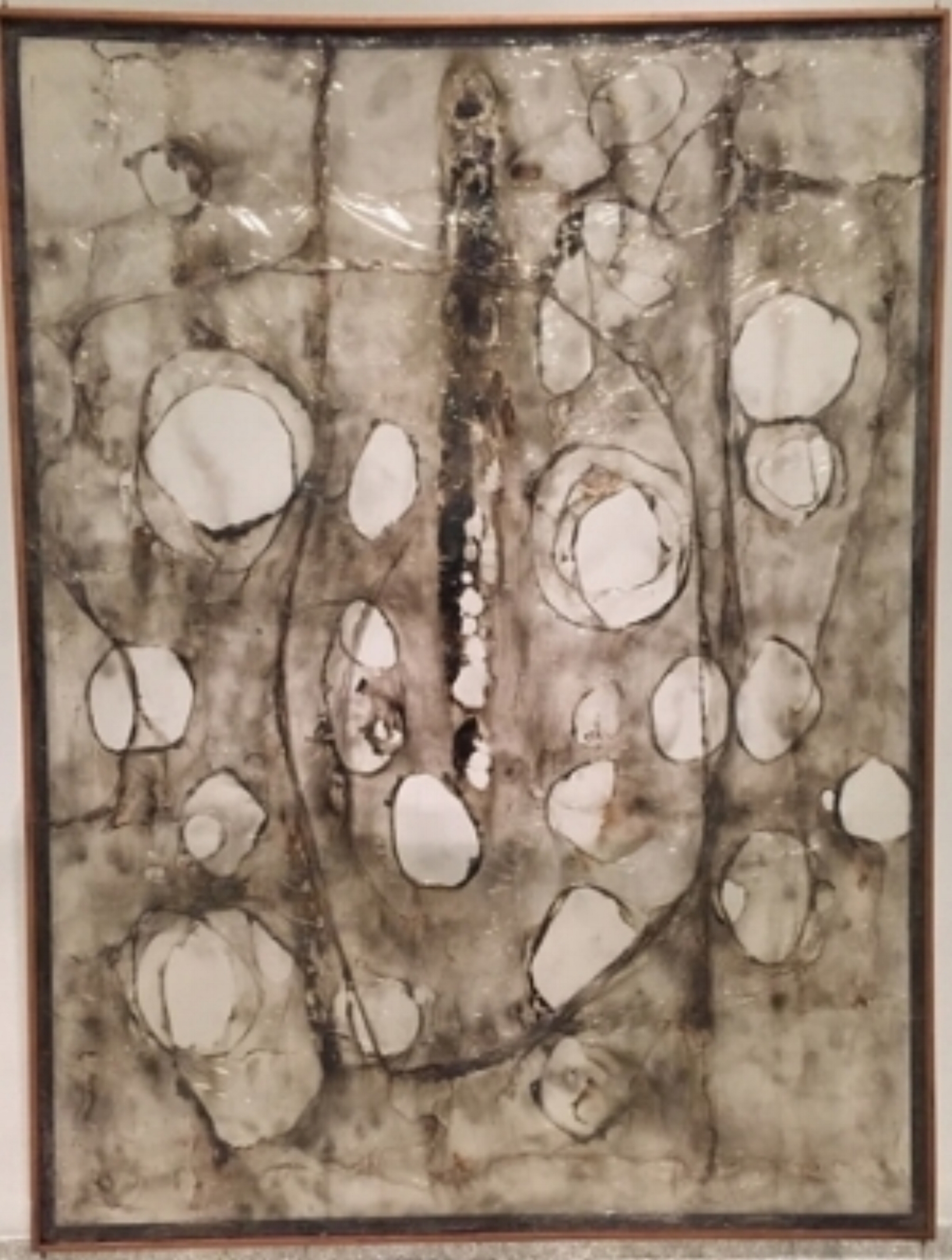

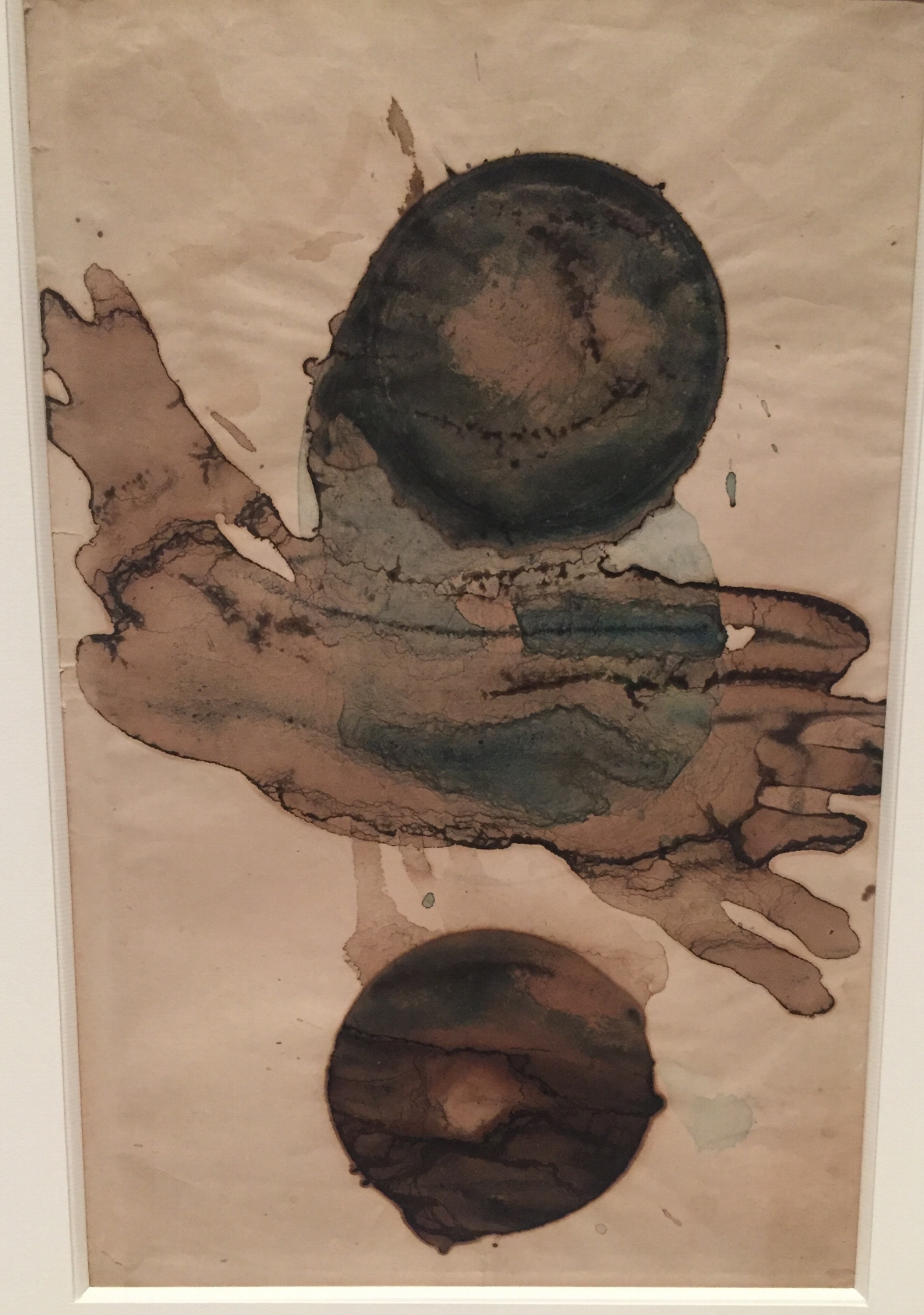

The exhibition of 75 drawings is titled Stones to Stains (Taches) as these were the methodologies with which he began and ended his drawing practice which took place largely while he was in exile for 20 years in Jersey and Guernsey, the Channel Islands to which he had repaired when political events continued their downward spiral. Not content to use the formal methods available to him, he creased, folded, puddled, stenciled, smudged, traced, collaged, frottaged, cut out, and literally shadow boxed with his paper. Though most of the drawings are a range of sepias, browns, beiges and blacks, it is the ones with a just a touch of polychrome that do stand out.

A highly romantic and skilled amateur of photography, astronomy, oceanography, and spiritualism, Hugo incorporated aspects of these passions into much of the work. Yet the work is not literal minded or illustrative. Instead as Pesenti reminds us, he took the simple tools with which he was writing Les Miserables and Notre Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre Dame) and other works—pen, paper, and ink—and gave them alternative expression in the drawings.

I imagine him late at night in Hauteville House, his splendid home on Guernsey which he decorated himself, after a long day of writing, taking out a clean sheet of paper and giving his automatic style which the surrealists eventually so admired, free reign, a release after the long day of keeping together his complex plots and syntax. Florian Rodari, a consulting curator on the project says in his excellent and enlightening catalog essay that he “defended disorder and the commotion of life”. He describes how Hugo looked on architecture as another alphabet, stones set upright, each one a letter, finally forming words in the ensemble.

Adele was not the only Hugo family victim. Her older sister Leopoldine, reportedly Hugo’s favorite, was drowned in a horrible accident along with her husband who tried to save her. Hugo had many devoted mistresses in addition to his wife and so we see the elements of the classic genius syndrome where geniuses are allowed things the rest of us are not.

Hugo did not sell his drawings. They were given to friends as gifts or aides-memoires of events, or eventually to publishers who used them in various publications, outlined in Burlingame’s catalog essay. The loans for this show, primarily from the Bibliotheque Nationale and the Maison of Victor Hugo in Paris will probably not be allowed to travel outside of France again, and the Hammer is the only venue Do watch the video of the curators in their behind the scenes of the creation of the exhibition.

Pesenti summons Odilon Redon, Andre Breton and Picasso, as artists akin to Hugo in various ways, but all I could think of was Alberto Burri, perhaps because I had so recently both written about his Guggenheim exhibition and the Gibellina Cretto.

The exhibition is open until the end of the year. The Hammer is screening the film on November 20 but it’s also for rent on Amazon. It’s a great warm up to the exhibition as it’s filmed almost entirely on Guernsey. And if you’ve ever been rejected in love, you will weep along with Adele as she tries to win back the favor of her lover. In real life, Truffaut, who often fell in love with his leading ladies, apparently was rebuffed by the much younger Isabel Adjani who played the role and she instead had an affair with her co star Bruce Robinson, who was also a very good writer. So real life imitated the art which imitated real life, precisely in keeping with the masterful Victor Hugo.

Images courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France, The Metropolitan Museum of Art / image source, Art Resource, NY, Collection of David Lachenmann, Maisons de Victor Hugo, Paris / Guernesey / Roger-Viollet, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon/François Jay.