“I remembered myself as a very small boy, already so bitter about the pledge of allegiance I could scarcely bring myself to say it…I was in short, but one generation removed from the south.”

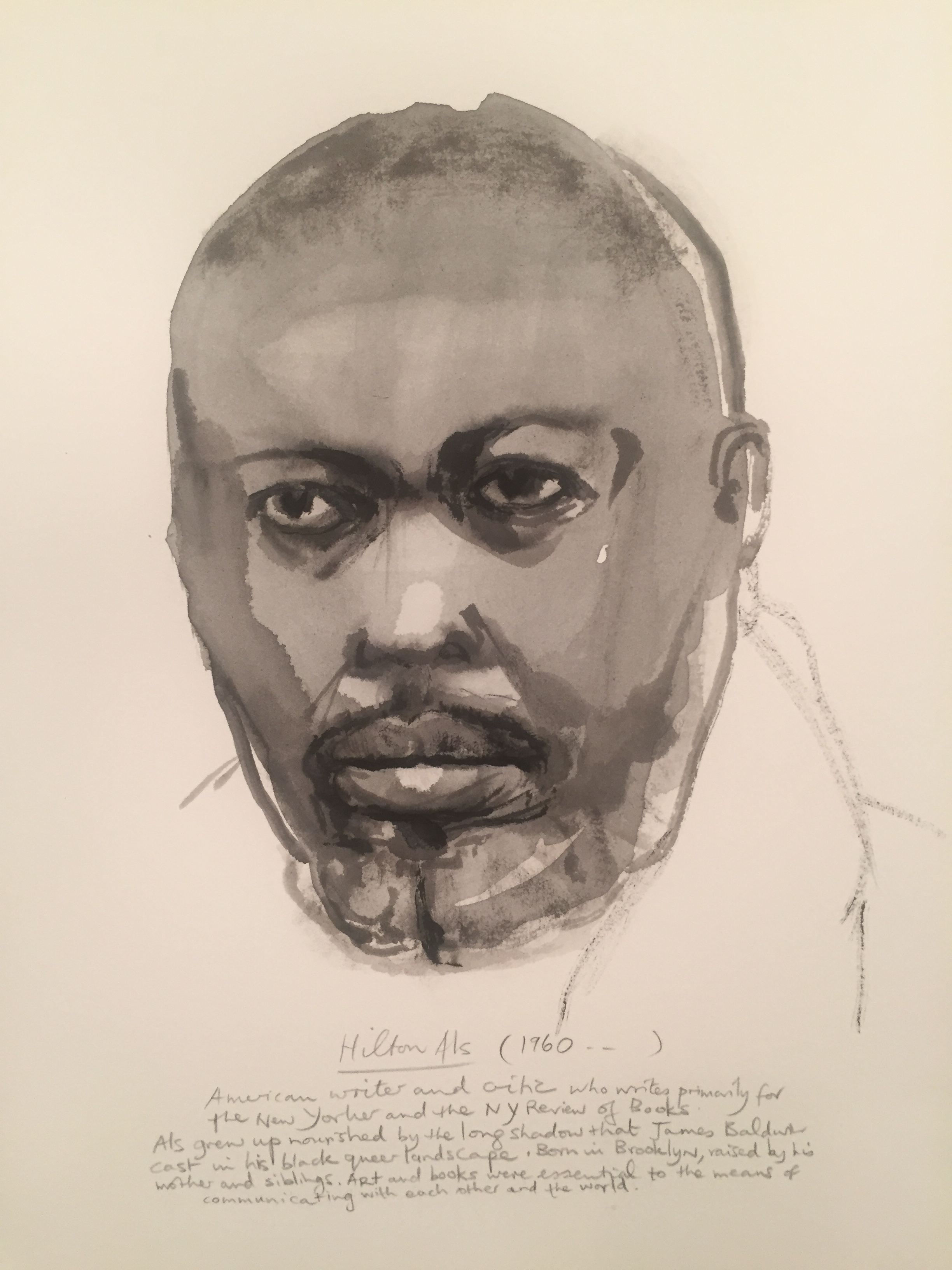

So opens the moving exhibition on James Baldwin, God Made My Face, curated by Hilton Als at David Zwirner. In two distinct sections, A Walker in the City and Colonialism, Als offers us original text and images as well as commentary by fellow artists.

“He will not be swiftly forgiven for having turned so many tables,” Baldwin writes of Michael Jackson. The same could have applied to Baldwin himself.

Baldwin had a fraught childhood: his mother fled from his real father and traveled north. His stepfather, a preacher, had 8 children with his mother and especially disfavored Baldwin. After trying to be comfortable in his own skin in Harlem, he escaped to Paris. As for so many of us, Paris was both the tonic and the siren we thought would let us be who we really were. You didn’t have to be black and homosexual to want to have the artistic freedom of Paris. His friends became his family.

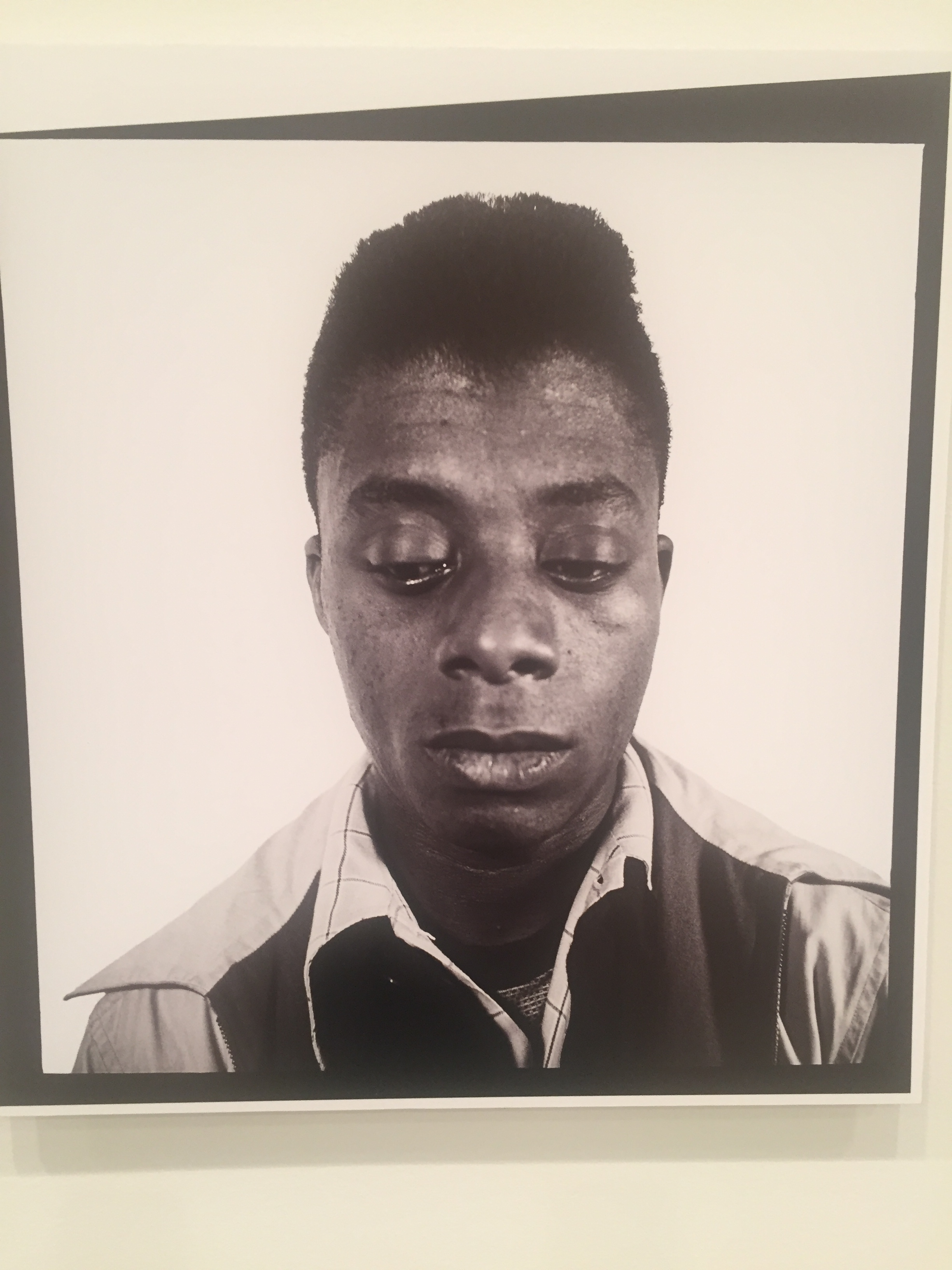

Baldwin had a slow but steady emergence from his painful chrysalis as a profound writer (original editions of the books are on display ). But he also kept a close eye on other forms of culture: film, theater, music, photography. His friendship with Richard Avedon began at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx (my father also attended) and they stayed close.

He was especially keen on filmmaking, but that did not work out as well as he had hoped. His métier instead was to dissect himself, his culture, the people and circumstances who had discouraged and pigeonholed him including his own family.

After publication of The Fire Next Timein 1963, Baldwin emerged as a leading cultural figure, one with agency. He then had more courage to take on battles larger than his own personal demons, ones that had long preoccupied him: the complicated legacy of civil rights, colonialism and its aftermath, miscengenation.

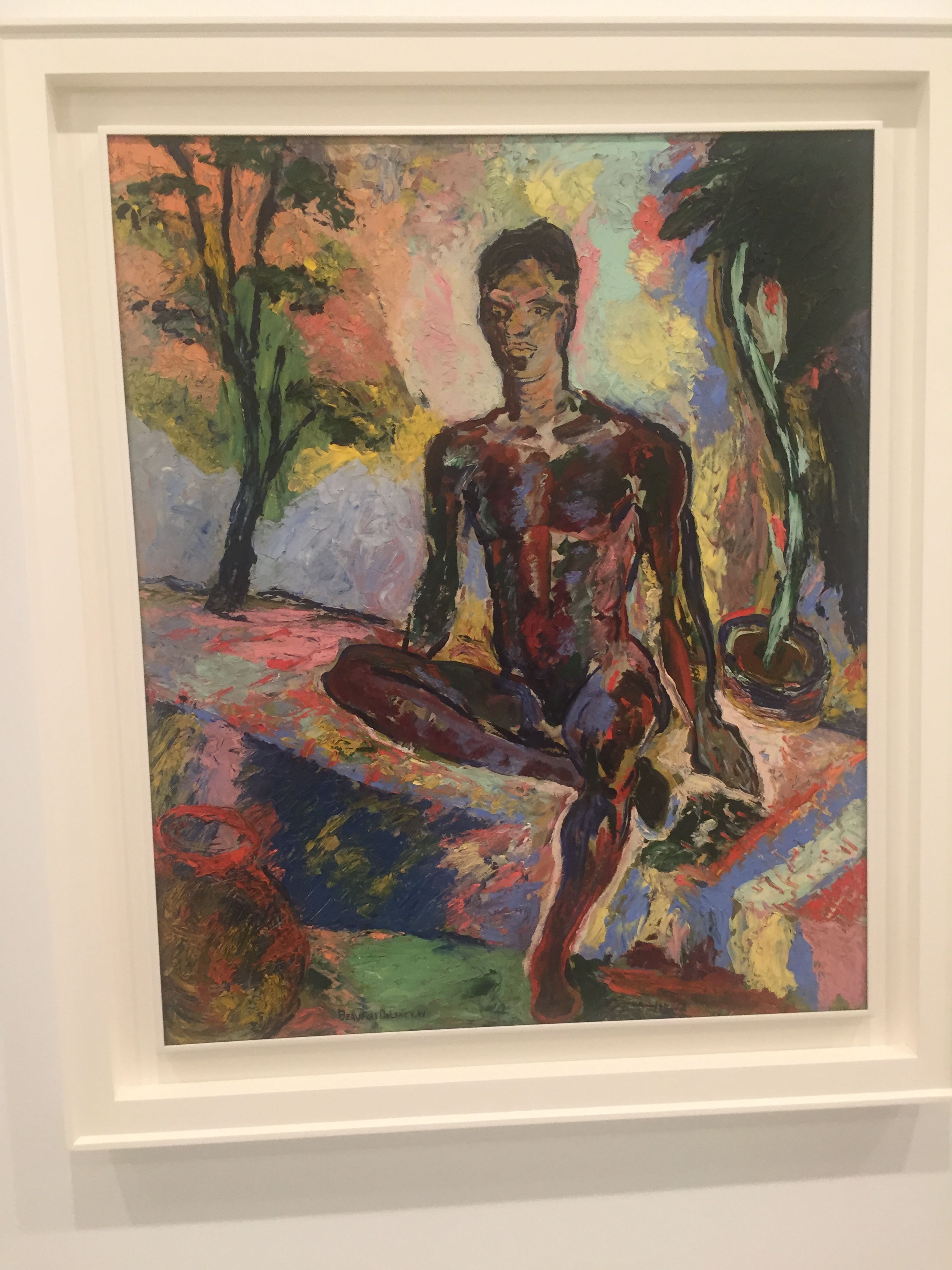

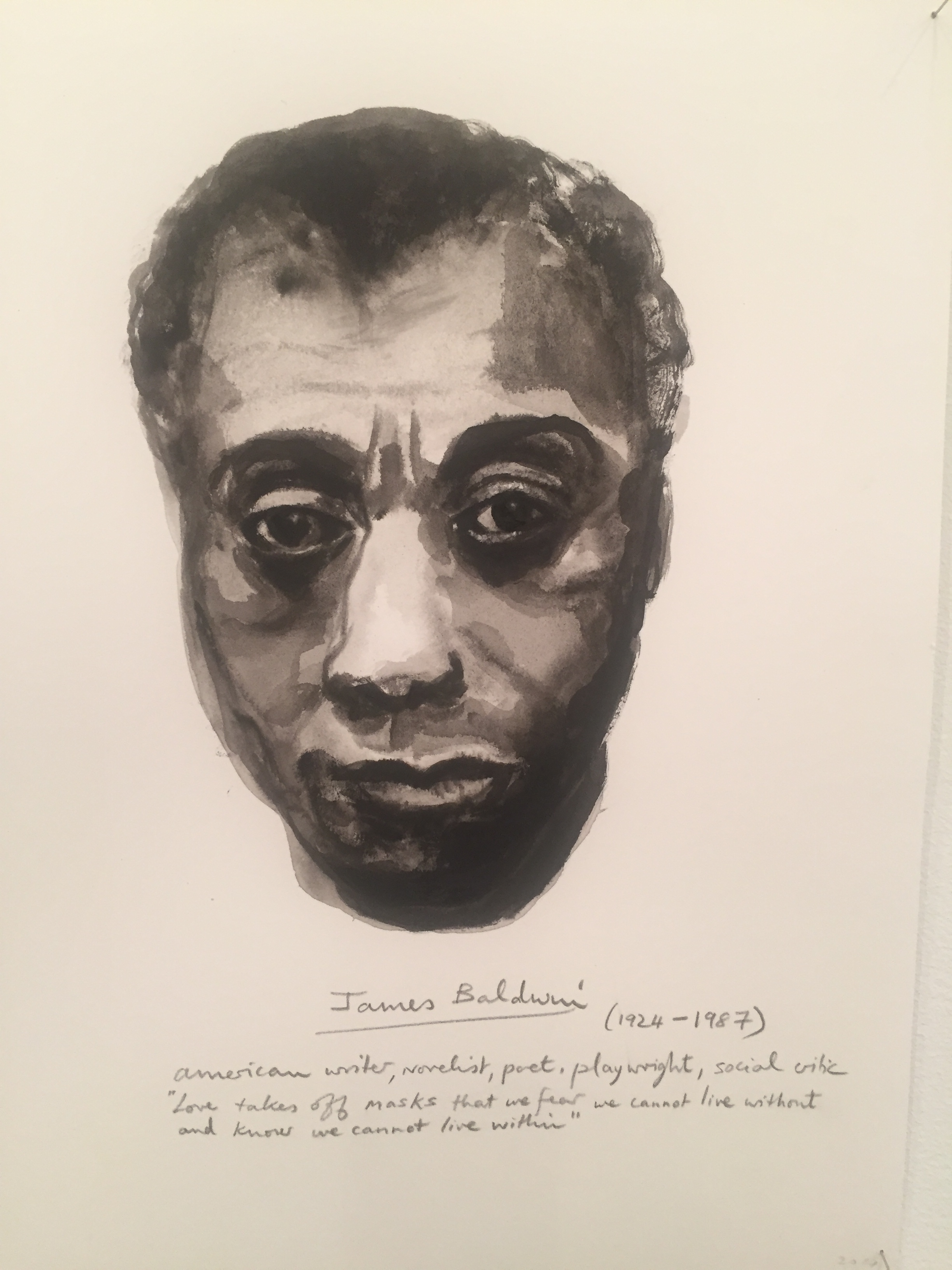

The topic of homosexuality was more challenging. Here at Zwirner, Glenn Ligon and John Edmonds weigh in on his behalf. Kara Walker, represented by her graphic film 8 Possible Beginnings,has never been abashed about telling it like it is. Marlene Dumas’s black and white watercolor series of writers and artists she periodically adds to imports a very personal dimension to some of Baldwin’s friends and contemporaries.

Curator Hilton Als himself seems to have picked up where Baldwin left off. Both as an excellent excavator of historical black culture (his last exhibition on Alice Neel also at Zwirner, was one of my favorites) and a supporter of contemporary black culture he excels. Yet he is a fluent about white culture as anyone.

With the film If Beale Street Could Talk and this exhibition, Baldwin re enters the culture for another generation.