Continuing in its restoration of the work of Jacques Rozier (see my story for Airmail on his Bardot film), the @CinemathequeFr has just loaded a charming early Jacques Rozier short, Blue Jeans, made when he was just 30, which showcases this early member of the Nouvelle Vague's insouciant take on life, love, and the Cote d’Azur. It's available for free on their Henri (named after the founder, Henri Langlois) channel, with English titles along with many other jewels.

This time we find ourselves with two young, gorgeous, hotshot drageurs (the French word for pickup artists is just so much more efficient) who wear tucked in white shirts and blue jeans (no longer called blue, but then, only blue, appropriated from the farm) who don't consider a day's work done until they have found some lovelies to share the night with. Hunting for prey on their Vespas in and around Cannes, they happen upon two wasp-waisted, short shorted, high heeled wearing beauties who fit the bill and after some to and fro, hop aboard to trip the life fantastic. The beach is the scene of their making out, their dancing (the chacha!) and eventually their come-uppance. Actual work plays no role, being on the make, without money, turns out to be a full-time pursuit. All this to a Cuban soundtrack that lifts the spirits. Jean Luc Godard wrote, " A buoyant short, young and beautiful like the body of a 20 year old as Arthur Rimbaud has described it."

Tokyo Ride

The film, Tokyo Ride, part of this year's Architecture & Design Film Festival begins in a rainstorm. Ryue Nishizawa-half of the Pritzker winning architectural duo SANAA- picks up filmmakers @bekalemoine (whose architecture films are in MoMA's collection) and after apologies for surprising the camera on him so soon, they begin a ride around Tokyo in Nishizawa's beloved Alfa Romeo whom he affectionately calls Giulia. And so begins a Cinema Verite, Nouvelle Vague-esque ride. It's utterly charming.

With a dour face that breaks into a smile, a Beatles bowl haircut and a straight man delivery, Nishizawa is an unconventional tour guide. In floral and polka dotted shirts, he opines on Tokyo, the differences between East and West architecture (Japanese people love newness; Europeans are armed, Japanese architecture like a verb, European like a noun, KenzoTange and Saarinen must have been in some kind of interstellar pre-internet communication etc). He loves Italian cars for their soulfulness, German cars are stricter and indeed the car is as much a character as the filmmakers who try to be unobtrusive but are part of the ride.

A visit to a soba shop for lunch is fun but the real eye opener is a visit to his partner Sejima's house which he designed for her and her parents.It has something of Eames in its plan and transparency but also traces of Mies and Le Corbu--his stated favorites. Sejima and Nishizawa expose their history of bickering (their personal relationship is somewhat mysterious, some larger projects done together, others individually) and if you ever wanted to know what goes on behind closed architectural doors, this is a great place to start. In her six inch platform shoes and Louise Brooks haircut she is both self effacing and determined. After a visit to her office (his, hers, their offices all in same building) and a tour of Tokyo stadiums, the film ends at the house of Nishizawa's friend and client Moriyama serving up some gorgeous take out sushi (don't see this film hungry).

I'm looking forward to other films about Paul Williams and Nakashima so check out the ADfilmfest website.

Agnes Varda's short film about LA heroines

Agnes Varda made a charming film The Little Story of Gwen from French Britanny portrait for her friend Gwen who is now the head programmer of the American Cinematheque in LA but who at one time was an emigre to Los Angeles. As is her wont, Varda took the simplest of subjects and went back and forward in time to make it personal, but universal: a young woman on the rebound, searches, and then finds, a new journey for her life. Varda's voice over is typically understated, drawing connections between the girl on the bicycle (what could be more French and non-LA) and every girl. See the full short film at American Cinemathique.

The mysteries behind Man Ray's Les Mysteres Du Chateau de De

In 1929 artist, photographer,filmmaker extraordinaire Man Ray was invited by one of his ardent patrons, the Vicomte de Noailles, and his infamous wife and partner in outlandishness, Marie-Laure, to their Robert Mallet-Stevens designed chateau in Hyeres, in the South of France, to shoot the house and its varying, dynamic collections as well as “make some of shots of his guests disporting themselves in the gymnasium and swimming pool,” according to Man Ray. As with many Surrealists who favored automatic writing, Man Ray favored a kind of automatic filmmaking. He looked upon film as another tool in his poetic, playful bag of tricks innovated with light but he had grown disenchanted as reality in the form of sound had begun to impose itself on the medium: improvisation was his preferred metier. Nevertheless, the Vicomte assured the artist that the film would be a documentary for their private viewing pleasure only, so Man Ray made an exception for the wealthy and generous man. Reminded of a Mallarme poem, “A throw of the Dice can Never do Away with Chance”, Man Ray decided to make, ‘chance’ the theme of the film. He brought with him two pairs of dice and six pairs of silk stockings which he intended to “pull over the heads of any persons that appeared in the film to help create mystery and anonymity.” Things being what they were at the Chateau, that is to say, already capricious with the beau mode in attendance, the film did not follow a neatly proscribed narrative.

Man Ray began shooting when he left Paris. Two men throw the dice, and leave for the south, arriving at the angular chateau—which is as much a character as anyone in the film. A couple throws the dice and decides to stay, then just as enigmatically to leave after another toss. Man Ray captured the right angles of the Mallet-Stevens modernist house, the painting archives, and eventually the frolicking guests shrouded in stockings and striped bathing suits as if in a phantasm. (Indoor gyms and exercise were all the rage in the late twenties; somehow the late nights and flamboyance had found a counterweight). The Vicomtesse appears in an underwater sequence with oranges in the glass-covered pool, a surreal Esther Williams; a stocking almost actually choked the Vicomte.

Les Mysteres du Chateau de De film also contains negative images akin to his signature Rayographs. This film was his last complete film. (By way of reference, the same year, Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou was released).

The Gagosian Gallery in San Francisco has a very engaging show with good quality prints of Les Mysteres and two other films and numerous objets and stills drawn from the films as well as a short history of the house, now the Villa Noailles, an artists retreat. In a time when most films are literal-minded, these instead make the viewer a participant who is obliged to connect the dots—and the dice.

MAN RAY

Film Still from Le mystère du Château du Dé, 1929

Gelatin silver print

11 13/16 x 14 9/16 inches

30 x 37 cm

© May Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris 2019

Image courtesy Gagosian Gallery

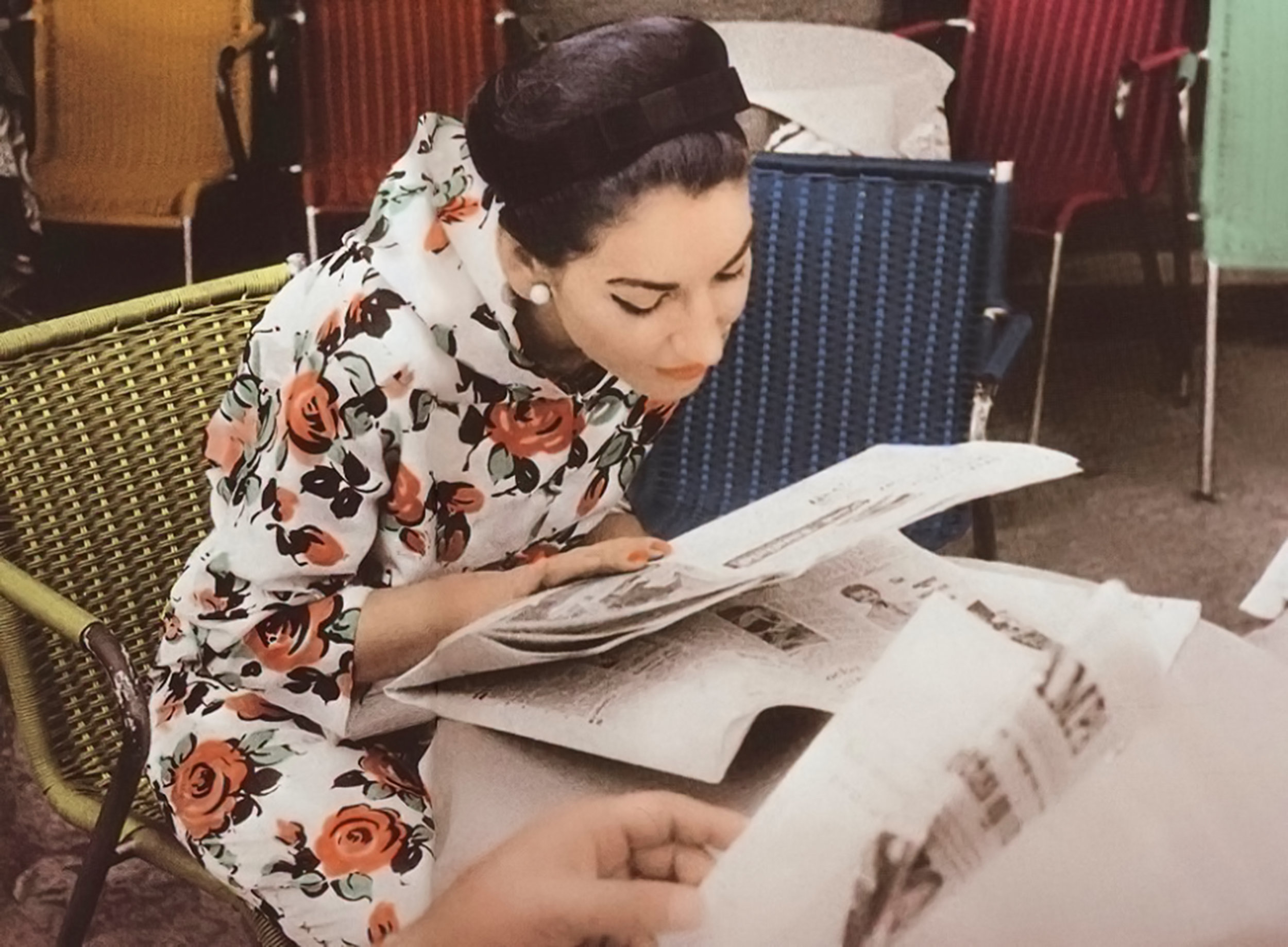

Maria by Callas: What does Diva really mean?

I write to the luscious tones of Maria Callas. Tom Volf, the director of the new documentary Maria by Callas fell in love with her voice only five years ago. He had a coup de foudre for all things Maria and it took him the better part of four years to pull off what is really a marvellous documentary.

Instead of talking heads, and a narration, la Callas, as she referred to her professional self, or Maria as she referred to her personal self, is captured in on-and-off the record interviews with Joyce di Donato standing in for her when she is momentarily absent. Entire songs rather than excerpts let you bathe in the voice, the mannerisms (I want the shawl, I want to hold my arms in a self-embrace, I want the bouffant hair).

Of course it’s the early years that fascinate. Born in New York City, she becomes a more elegant and refined citizen of no country with the haute accent that goes along with that. The pudgy prodigy, nudged by her mother to Greece for training with a Spanish diva who is discovered early on becomes the leading bel canto singer of her generation.

The images of her looking up at the camera, the cat eyes, the wide mouth, they are indelible. Besides her voice, she knew what her assets were.

The dramatic career buttressed by the long affair with Aristotle Onassis, interrupted by an equally ambitious Jacqueline Kennedy, and then a rapprochement when La JO had had enough is grand opera in itself. Don’t ever let great artists con you by saying their lives are separate from their work.

If you don’t know Callas, Amazon Prime has a lot of free Callas, and there is You Tube. But the film is special, the house was packed Saturday night in NY at the Paris Theater, I could only think with Met opera goers who were not at the opera itself (Callas warred with the Met much of her career).

The film is a brilliant look at what goes into being a celebrity of any decade.

We talk about divas. There are divas and then there are Divas. Callas was the latter.

Becoming Astrid: a film about the real-life Pippi Longstocking

My office library is organized by subject matter. Non fiction—biography and memoir—load most of the shelves. Fiction is in the bedroom—hardcover—and art books in the den. The children’s books are still in one of the rooms once occupied by my youngest son.

But on the two shelves above my desk are the books which are the most personal. The series of French film books and DVDs of the New Wave, the books by friends which have been inscribed to me by their authors, and a short selection of novels and non fiction which reference my current work.

On the very top shelf, in the middle, now encased in a plastic baggie as it’s so fragile is the paperback version of Pippi Longstocking which I ordered as part of the Scholastic book club in elementary school. The binding is shot, the pages are brittle and many are loose and have disengaged from their mooring.

I know I am far from the only girl, or person, who nourishes such fond affection for a novel which found in me the brave girl I wanted to be, who didn’t give a fig for what anyone else thought, who could climb trees and wash the floor as if she were skating, had a horse in her backyard and was so strong she could lift him, who made excellent pancakes, who could sleep whenever and however she liked, join the circus, and had a pet monkey and was so nice to the more conventional children next door.

Author Astrid Lindgren found her way to millions of childrens’ hearts all over the world because, as one says in a letter she receives when she is very old in a new film biography from Sweden, “ You understand us Astrid, you are on our side”.

Becoming Astrid directed by Pernille Fischer Christensen tells the fairly conventional story of an unconventional girl: a rebellious farmgirl with talent who leaves her family behind as her talent is recognized, and along the way has a affair which changes the course of her life, but only serves to deepen her ability to understand how a child feels.

And it shows in a very simple way how it’s impossible to entirely separate the writer from the document no matter how much they (we) protest.

Like Laura Ingalls Wilder, Lindgren took the basics of her own life and put them into her stories; she wrote many more books but Pippi is the one best known to English speaking audiences.

I don’t really want to spoil the film for anyone. Alas I believe one sex scene would make it difficult for anyone younger than middle school or high school to see it, it’s really a film for older teenagers and adults.

I took an informal survey of friends. Everyone identified with Pippi. Like Eloise and Madeline she is smart but feisty, all three of them girls who prevail in the end just by being themselves.

The film is perfect holiday treat about loss and forgiveness, following your passion, the clichés of growing up and out which are all too true. A new generation is discovering the marvels of Pippi every day.

It opens on November 23rd.

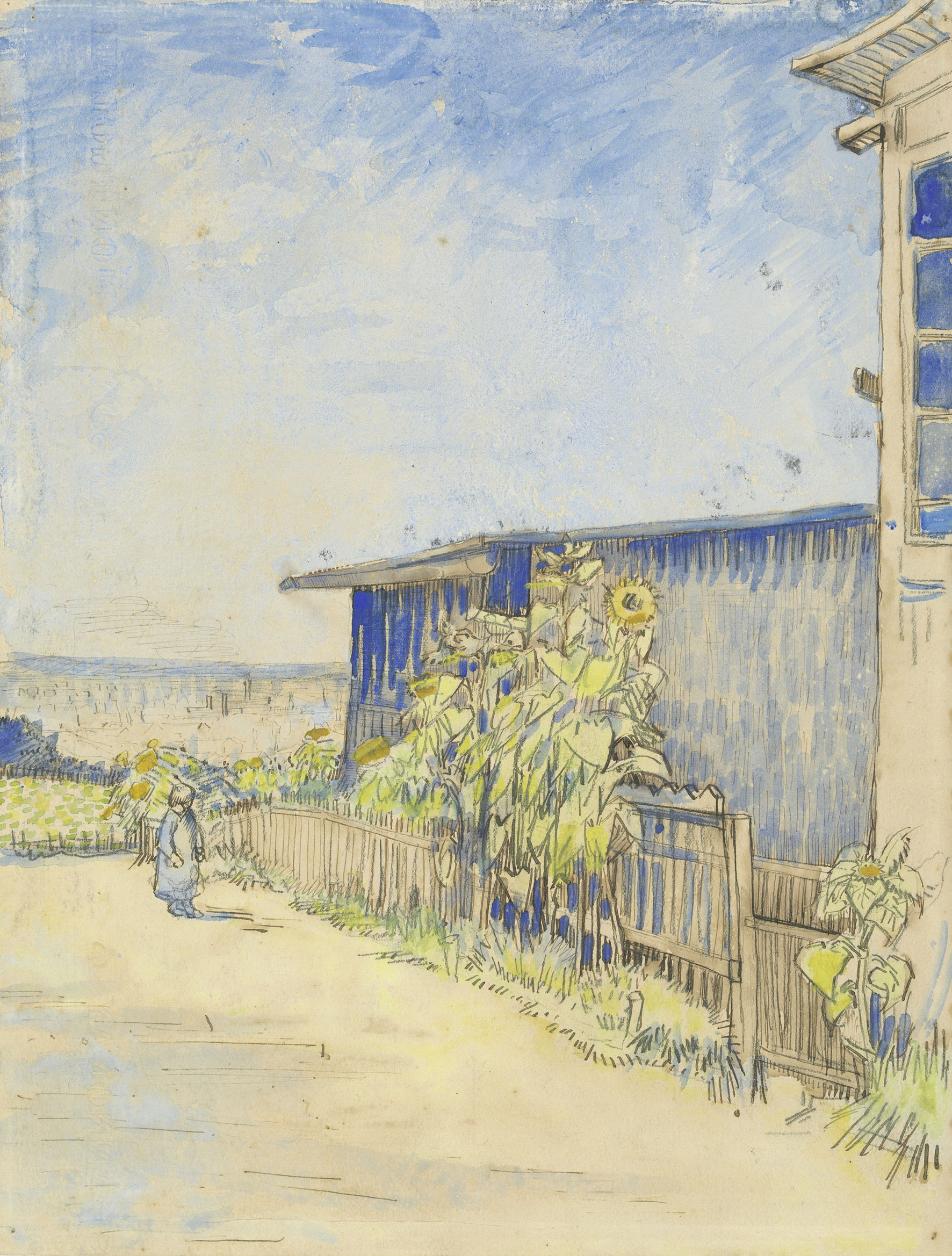

Van Gogh by Julian Schnabel: At Eternity's Gate

Julian Schnabel is a very brave artist. After being a wildly successful artist du jour and then coming down off that perch, he turned his hand to film and made, among others, some beauties: the story of Basquiat and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.

At Eternity’s Gate, his film portrait of Van Gogh is as ambitious as the others but is hampered more than anything by the dialog seemingly lifted in whole chunks from letters that Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo, to Paul Gauguin fellow artist, and others. Despite help from veteran screenwriter Jean Claude Carriere (or maybe alas because of it) nothing ever sounds natural. And therefore the performances, though earnest and deep, draw attention to their static quality instead of to their verisimilitude. Schnabel should have trusted himself more.

Instead of bringing on a French screenwriter, the casting could have been more European. Not that I am PC about that. But the American-ness and British-ness of the principal roles doesn’t help you dive into the characters.

Willem Dafoe is abjectly tortured, (even if a good thirty years older than the artist actually was as this series of events unfolds), the artist who can’t get anyone to even hang his work for free in a bar, whose manic depression overwhelms him, whose obsessions for capturing on canvas a girl walking home from work or a fellow asylum mate get him into trouble. His compulsive desire to fill every canvas, to layer it, to exhaust the paint itself, is made real and here Schnabel’s own expertise comes into play. We feel keenly his desire to suck up the sights, sounds and even smells of the world.

Oscar Isaac is a suitably arrogant Gauguin who alternately thrills and chills his less successful friend. The best surprise is Rupert Friend as brother Theo.

This relationship of the brothers is wonderfully drawn: Theo the sane, Vincent the genius madman, linked forever as helper and helpless. Theo’s desire for his own life eventually overrides his compassion for Vincent when he institutionalizes him.

Van Gogh’s intellectual heft, his knowledge of Shakespeare and the Bible is set against his dramatic deficits of personal intelligence. I don’t know if Schnabel invented this or it was real. (I reached out to John Walsh, ex Getty director, now giving a series of lectures on Van Gogh at Yale open to the public for some context. Walsh reminded me he would be dealing with this period in Arles next semester .)

The production is filled with the southern French light that so warmed Van Gogh’s aching heart and soul. (Arles, once a favorite city of mine, is now undergoing massive development by the Luma Foundation. I saw things in construction a few years ago. I’m hopeful they can retain something of the city’s historic character) Schnabel managed to find the still rural Arles, the one that was Van Gogh’s home at the end of his life both inside outside the asylum walls.

Every loaf of bread, bowl of fruit and indeed every character from barmaid to priest is filled with the unique texture of real life. And then every once in a while the screen goes black. A moment of darkness descends on us just as it does on Vincent.

The film opens on November 16th.

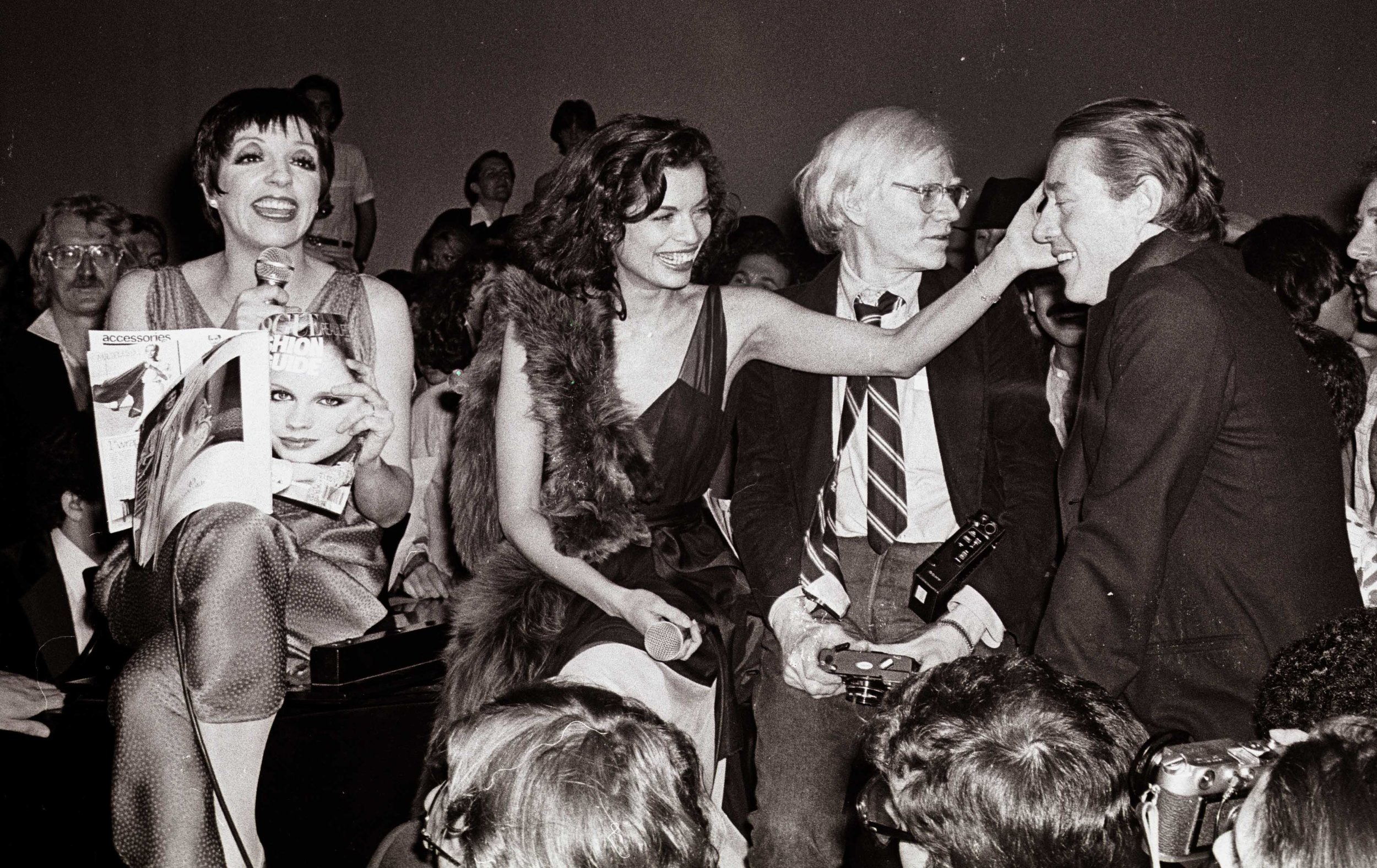

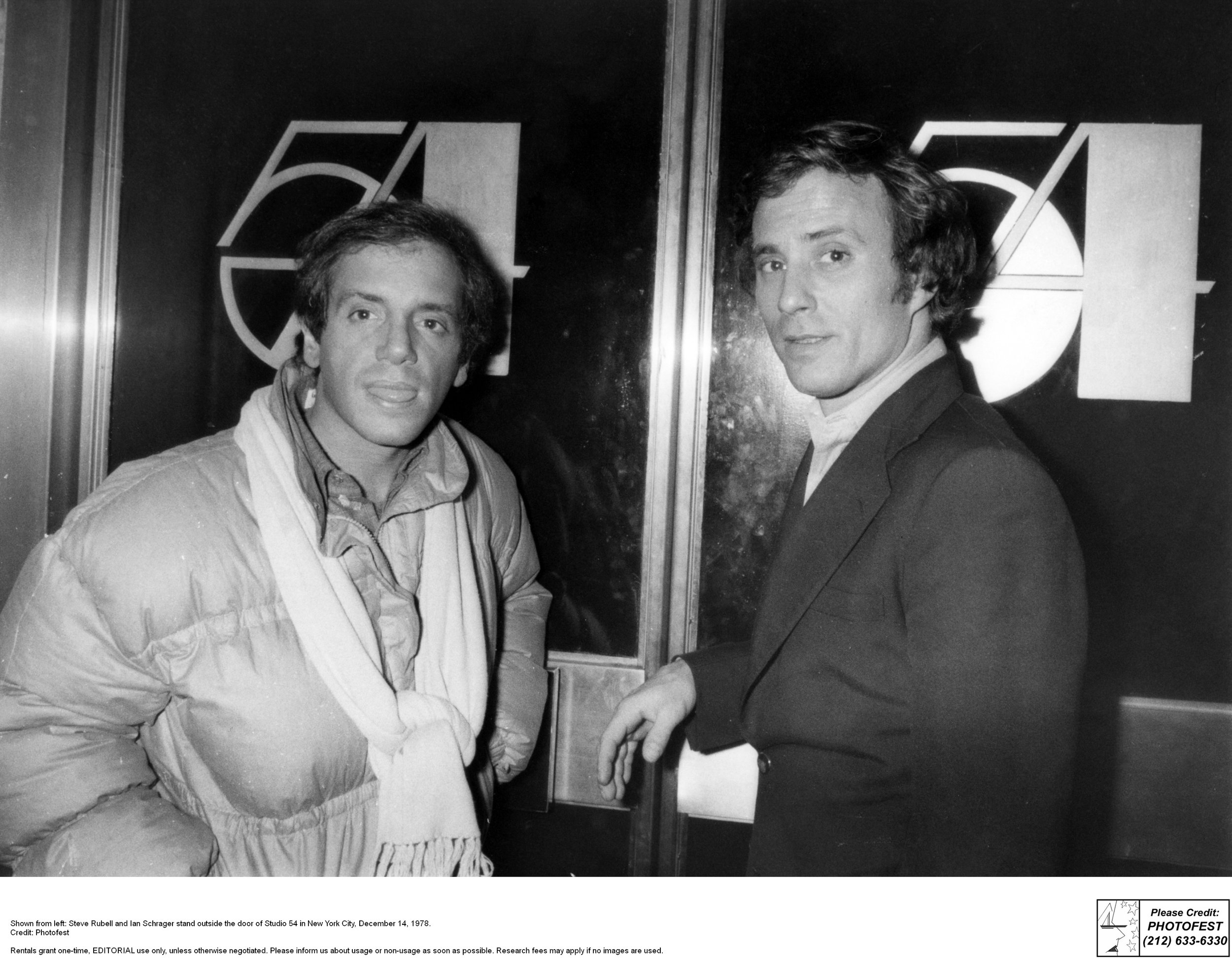

Studio 54: A new film brings back the highs and lows

Nostalgia is a funny thing. Am I regretting the jackets with shoulder pads that added heft but not necessarily strength? How about that picture of me with hair that looked like a magnolia tree? Every couple of years it seems fashion and art loop us back to a decade about which I have very mixed feelings. First it was the 60’s, then the 80’s. Now the 70’s are grabbing hold.

Almost concurrently with a giant retrospective of Andy Warhol’s work due soon at the Whitney comes Matt Tyrnauer’s documentary on Studio 54. Or “Studio” as the owners, Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager and anyone who was anyone referred to it. Warhol hung at Studio. So did Liza Minelli, and Halston, and Bianca Jagger and Capote.

That did not include me. Oh, I don’t mean to suggest I was a victim of the velvet rope. In fact, my boyfriend in college belonged to a fraternity in which Rubell and Schrager were older brothers, already besties, and I met them at events and so it was not impossible to think I could have become a denizen. The journey of these two Brooklyn boys who remained soulmates and partners until Rubell died of AIDS is the film’s narrative spine. I did not know that Schrager’s father was a mobster but it makes perfect sense in light of what eventually befell him. I suppose you can learn the grift at the knee just like woodworking.

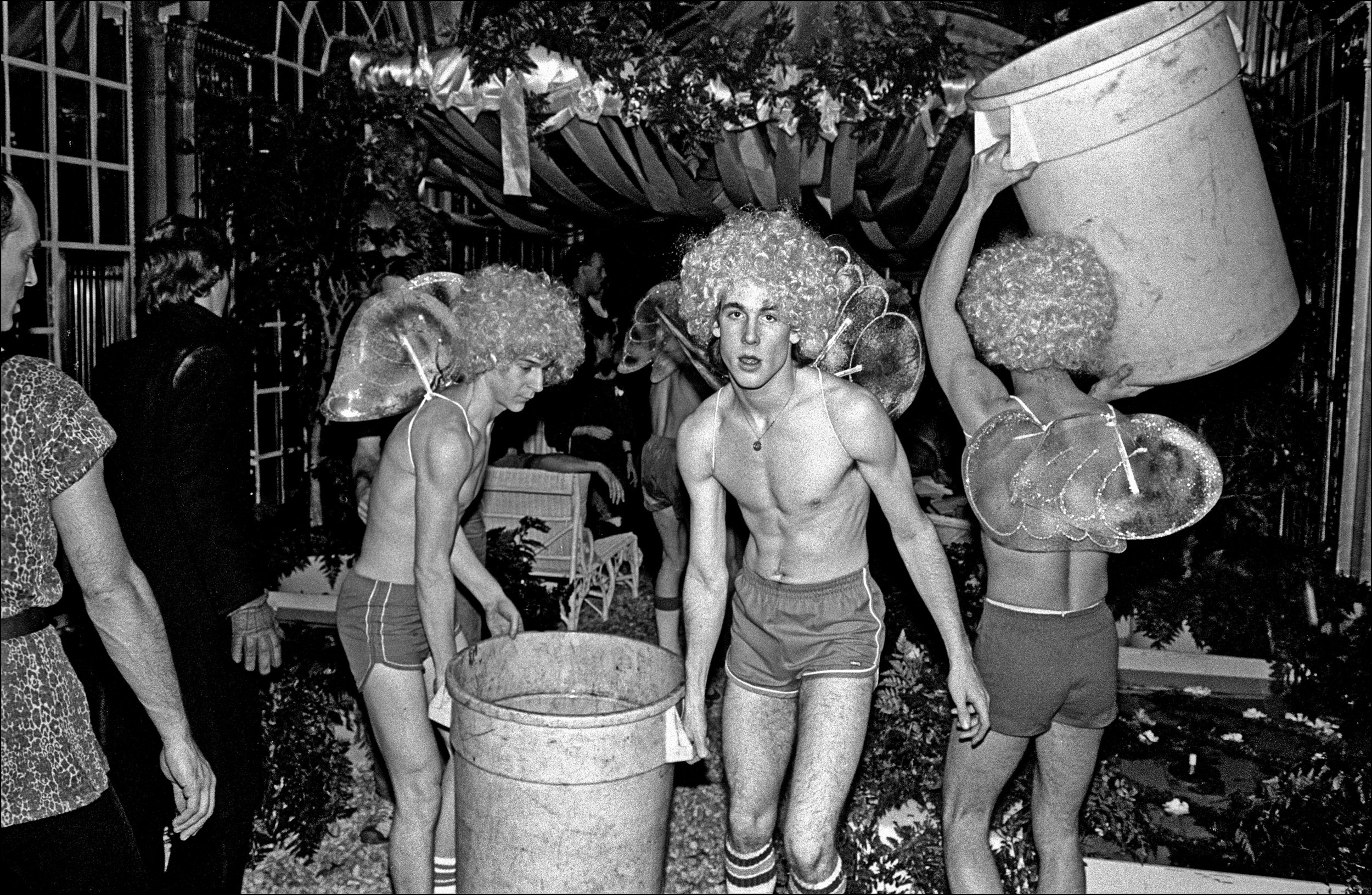

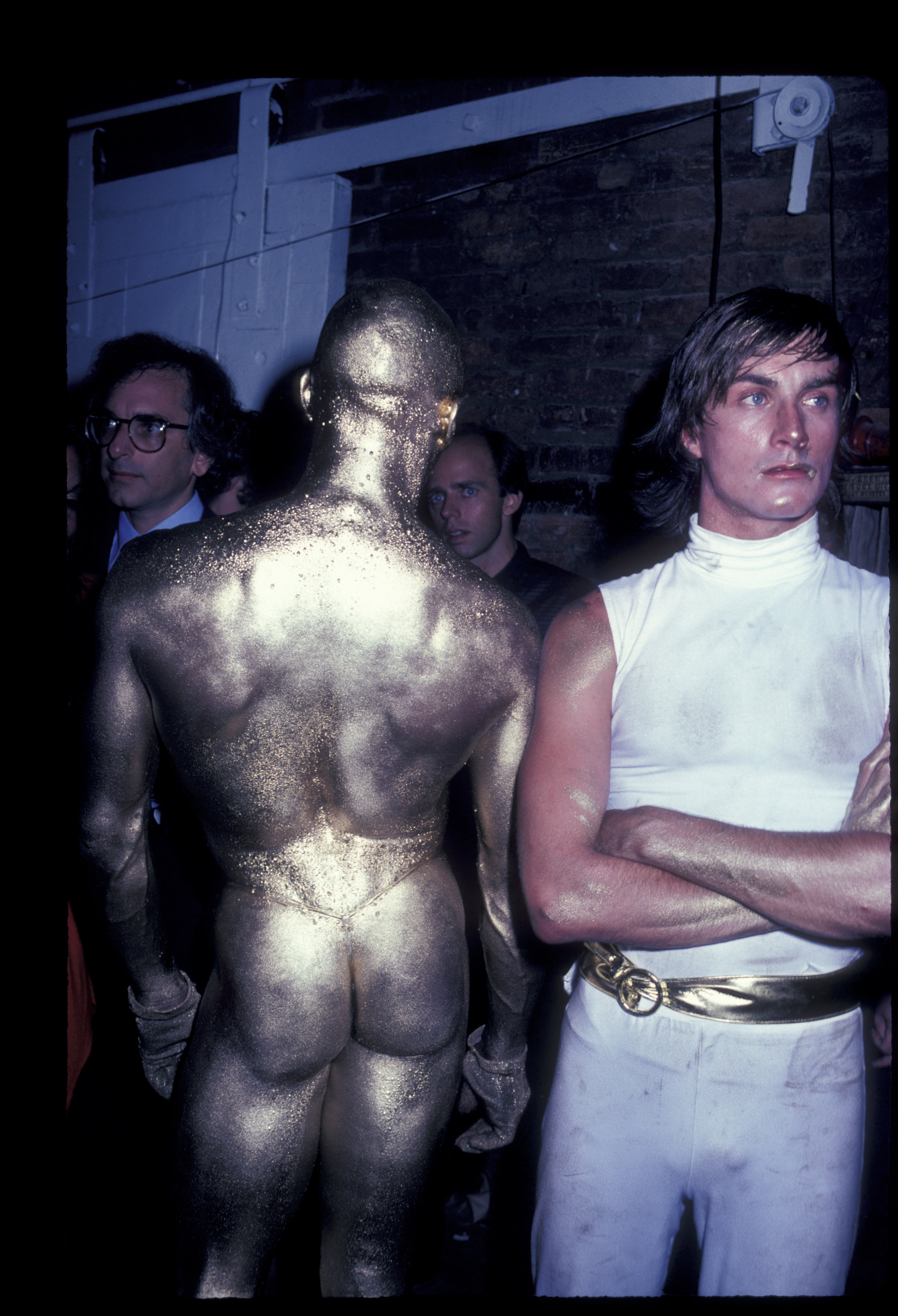

But truth be told, Studio 54 terrified me. Walking in there reminded me of Dead concerts only better dressed, or mostly undressed, but with the same lighting and tripped-out sweaty scene that brought back intense acid flashbacks. Representing as it did the age of celebrity mixed with the toxicity of drugs, the scourge of AIDS, and then the revelation that the two owners were crooks, Studio 54 took the temperature of the 70’s with a vengeance.

Club culture, until then decidedly fringe, became mainstream. The place to see and be seen. Dancing--which I did love-- took on an added sexual dimension, a way to hook up, especially if you were gay. The documentary is replete with interviews with the worker-bee non-celebrities: the silent investor, the Rubell brother, the door guy, the lighting guy, the accountant, and a narration provided largely by Schrager who by the looks of it can’t decide if he’s really contrite about his tax evasions, or not. Events, he implies, got away from them. The headiness of being at the epicenter of a certain cultural zeitgeist was too tempting to resist. He almost seems bemused by his follies, his stay in prison.

I’m trying to decide if anyone who did not live through that era will find Studio 54 avant garde or totally retro. Nobody knows who Minelli and Halston are anymore. Nobody knows that Capote totally combusted after his novel Answered Prayers, which contained a infamous chapter on the rich who had supported him, abandoned him, precipitating a fall into alchoholism and drug addiction similar to many of the celebs at Studio 54. How was it to have close friends and colleagues in the culture world get sick with AIDS, keep it a secret until they couldn’t anymore and then die? It was a brutal era, less optimistic than the decade that preceded it, and it gradually gave way to a New York which was all about money.

Tyrnauer, who has had his eye on more intellectual residents of NY as well, does a good job conveying the madness and the mayhem. But in the end,though the ostensible through line is the ‘freedom’ that Studio 54 purportedly made its regulars feel, the documentary made me sad for all the missing persons and not at all nostalgic for this aspect of the seventies when being able to do whatever you wanted began to seem like the scariest thing in the world.

The film opens in NY on October 5 and then rolls out across the country. I’m curious to see how it does outside the NY region.

Kusama-Infinity film documents the bumpy journey of an art star

I came to the Kusama-Infinity film by Heather Lenz a skeptic and emerged something of a convert.

There isn’t one city I’ve visited in the last years that has not had a Kusama retrospective recently completed, up, or on the horizon. Museums fight to get a Kusama show, attendance increases dramatically when they land one. Who does not covet a selfie with a Kusama?

It was not always thus. Lenz’s film makes a strong case for another Kusama, the outsider who came to the US in 1958 with money sewn into her kimono at a time when Japan was stifling and reactionary after the war. Her family—in the seed and flower business—did not recognize or support her talent. Her father was a philanderer and filled her mother with anger which spilled over into the children. To escape this toxicity was bold and rare.

New York held its own challenges. Kusama was neither Ab Ex nor Minimalist nor Figurative. Maybe she had a little bit of Pollock’s energy—less drippy- and Agnes Martin’s precision—less restrained. She could not get arrested (later this would change). But Kusama had extraordinary belief in herself and her work. She was very striking. She recognized early on the value of documenting her work, and her person. Artfully draped over her or standing amongst her creations, she is every bit as arresting.

Finally, in some smaller shows, other artists began to see her value and innovation. There’s no doubt that Oldenburg—stuffing—Samaras—mirrors—and Warhol—immersive patterned installations—and later Hirst-dots--were inspired by her. Stella craved and eventually bought an early yellow work for 75 dollars. Cornell had a crush on her, called her “my princess’ even though he was celibate (as was she.)

She cycled through obsessions with dots, infinity nets, balls, stuffed fingers, mirrors, naked happenings and protests. She was against the war in Vietnam. She did get arrested. I could not help but think of Yoko on a parallel path at this point only instead in bed with a Beatle. Kusama was in bed with her dots and fingers. I also glimpsed affinities with Rei Kawakubo. And with Ruth Asawa, another outsider who marched to her own net-like drums.

Finally she moved back to Japan and eventually she had to check herself into a psychiatric facility, where she still sleeps each night. Being obessesive compulsive and celibate? I don’t know how she was able to survive.

“When I see dots my eyes get brighter”, she now says with her signature red wig. Alas, though I very much appreciate the earlier work, mine now glaze over when I see the red and white dots. But I’m an admirer of the grit and determination with which she has approached her life and practice.

The film is in general release