Julian Schnabel is a very brave artist. After being a wildly successful artist du jour and then coming down off that perch, he turned his hand to film and made, among others, some beauties: the story of Basquiat and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.

At Eternity’s Gate, his film portrait of Van Gogh is as ambitious as the others but is hampered more than anything by the dialog seemingly lifted in whole chunks from letters that Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo, to Paul Gauguin fellow artist, and others. Despite help from veteran screenwriter Jean Claude Carriere (or maybe alas because of it) nothing ever sounds natural. And therefore the performances, though earnest and deep, draw attention to their static quality instead of to their verisimilitude. Schnabel should have trusted himself more.

Instead of bringing on a French screenwriter, the casting could have been more European. Not that I am PC about that. But the American-ness and British-ness of the principal roles doesn’t help you dive into the characters.

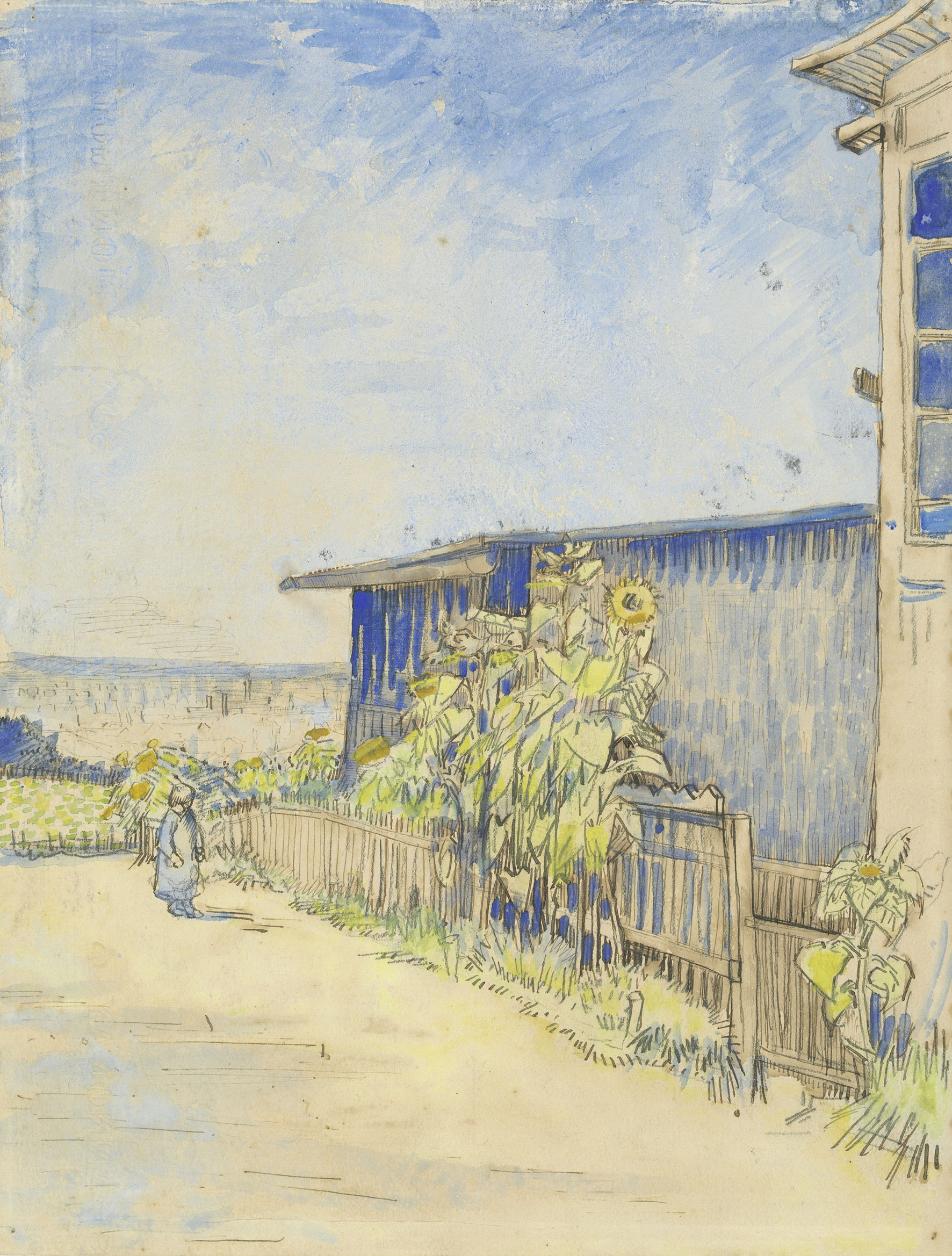

Willem Dafoe is abjectly tortured, (even if a good thirty years older than the artist actually was as this series of events unfolds), the artist who can’t get anyone to even hang his work for free in a bar, whose manic depression overwhelms him, whose obsessions for capturing on canvas a girl walking home from work or a fellow asylum mate get him into trouble. His compulsive desire to fill every canvas, to layer it, to exhaust the paint itself, is made real and here Schnabel’s own expertise comes into play. We feel keenly his desire to suck up the sights, sounds and even smells of the world.

Oscar Isaac is a suitably arrogant Gauguin who alternately thrills and chills his less successful friend. The best surprise is Rupert Friend as brother Theo.

This relationship of the brothers is wonderfully drawn: Theo the sane, Vincent the genius madman, linked forever as helper and helpless. Theo’s desire for his own life eventually overrides his compassion for Vincent when he institutionalizes him.

Van Gogh’s intellectual heft, his knowledge of Shakespeare and the Bible is set against his dramatic deficits of personal intelligence. I don’t know if Schnabel invented this or it was real. (I reached out to John Walsh, ex Getty director, now giving a series of lectures on Van Gogh at Yale open to the public for some context. Walsh reminded me he would be dealing with this period in Arles next semester .)

The production is filled with the southern French light that so warmed Van Gogh’s aching heart and soul. (Arles, once a favorite city of mine, is now undergoing massive development by the Luma Foundation. I saw things in construction a few years ago. I’m hopeful they can retain something of the city’s historic character) Schnabel managed to find the still rural Arles, the one that was Van Gogh’s home at the end of his life both inside outside the asylum walls.

Every loaf of bread, bowl of fruit and indeed every character from barmaid to priest is filled with the unique texture of real life. And then every once in a while the screen goes black. A moment of darkness descends on us just as it does on Vincent.

The film opens on November 16th.