I always wanted a daughter and now with her newest novel Wayward, Dana Spiotta has shown me what that must truly be like. Her previous novels-Innocents and Others, Stone Arabia, Eat the Document and Lightning Field--had through lines around music, art, and film which brought them close to my experience. In Wayward she also hits another of my my sweet spots: architecture.

Spiotta has a way of rounding up the usual suspects and making them personal and new at the same time. Wayward, ostensibly the story of a woman facing mid-life and aging and getting lost along the way (who doesn't?), still manages to pull the rabbit out of the two stories, told by Sam (the mother) and Ally (the daughter).

Sam separates from her husband because she falls in love with an old house which becomes the vessel for her confusion and frustration with her marriage. She cherishes the tiles, the wood, the way the light comes in through the stained glass windows. Everything that is no longer cozy and even sensual in her marriage comes alive again in her cottage. The joy of finding the proverbial room of one’s own. That it's the wrong side of the tracks just like her marriage is only sinks in later when she's the witness to violence.

But she's also obsessed with her daughter, trying to parse her every move, watching her mature--she has a relationship with a much older man, a friend of her fathers-afraid for her, paralleling her own maturation which is heading instead towards infertility, not new life.

Sam tries to rebound off the Trump election. She fine tunes her body as she is rehabbing her house. She investigates its history, searching for clues about how another woman made a life. She even made me feel affection for Syracuse, a city for which I thought I could never feel anything positive.

I interviewed Spiotta in 2016 and was able to post some images of her about Ally's age. Take a look.

An Homage to Janet Malcolm

When I first became a "Janet Malcolm person", I was a producer, and her multi-part New Yorker saga about The Journalist and The Murderer became the point de depart for a film project about a journalist who betrays her subject. I even lured Costa Gavras to direct. We sat for months parsing her story and its implications.

The movie didn't get made (too long a story for this post) but Malcolm and all her take-no-prisoners investigations always managed to find a certain application to my life (by then as a journalist).

Her two-year long series of interviews with painter David Salle in which she examined him refracted in what she called Forty-one False Starts, became a totem. The subject is a famous artist conscious of the slope and presentation of his career and a journalist, ever more cognizant of the shifting sands of the 'truth".

A couple of Malcolm gems from that New Yorker piece:

"He [Salle] is the most authoritative exemplar of the movement [post modernism], which has made a kind of mockery of art history, treating the canon of world art as if it were a gigantic, dog-eared catalogue crammed with tempting buys and equipped with a helpful twenty-four-hour-a-day 800 number."

"To the writer, the painter is a fortunate alter ego, an embodiment of the sensuality and exteriority that he has abjured to pursue his invisible, odorless calling. The writer comes to the places where traces of making can actually be seen and smelled and touched expecting to be inspired and enabled, possibly even cured."

In the perfect coda, Salle has gone on to become a very good writer about art himself. Malcolm rubbed off. Her unique take on the world will be very missed.

Tiny in the Air” (1989), one of David Salle’s tapestry paintings illustrated that piece.

CultureZohn Book Club

Sunday Reading: Two books that will take you inside the minds of artists- though very differently. Rachel Cusk departs from her trilogy and her unflinching memoirs to look at the intersection between one woman’s fantasy about an artist and the real thing when the artist she has admired from a distance takes up residence in her guest house. What ensues opens her eyes to the fact that artists: they’re just like us- as needy, as complicated, as tortured by insecurities and achievement. Celia Paul’s memoir of her life-with and without Lucian Freud-is another unvarnished look at what it’s like to be in thrall to a powerful artist and try to maintain an equilibrium for yourself and your own work. In both cases, these talented women must lose their sense of powerlessness and return to their own creativity to survive.

Robert Storr's Writings on Art

Robert Storr's collection of his Writings on Art 1980-2005, the first of a projected two-volume anthology, is enough to want to make any writer about art or culture roll over and give up. No way to compete. Storr, whose work I have long admired, is herein seen as not only an advocate of artists but as a communicator of the highest order. As an artist himself who worked at many trades in many locations before settling into a paying gig of criticism( he calls himself "The Accidental Critic") is at once clear eyed and fine grained. He debunks the idea of it being a 'career", and with that I am in full sympathy. Anyone who goes into writing about arts and culture needs to have their eyes wide shut.

A great aunt, then Bill Rubin, then artists like Christo, Frank Stella, Oldenburg, Jasper Johns and Siquieros, gave him an up close view. Lee Krasner gave him his inaugural lesson in the "sexual politics of art". I was only sorry to not know even more about Storr's personal history and his interactions with artists. Included are essays--a marvel of information and insight-- and excellent illustrations of. among others, the work of Louise Bourgeois,Peter Saul, Yvonne Rainer, Jean-Miche lBasquiat, Ilya Kabakov, Carroll Dunham, Arshile Gorky, and Philip Guston, whose work he championed early on.

When I wrote about MoMA last year for AirMail, I spent many many virtual hours in the archives reading interviews with curators, donors and staff. Storr's oral history was among the most candid and refreshing. He was brought on by Kirk Varnedoe to make more of a place for contemporary art at the museum, and his unvarnished reflections of his employ there are fully accessible at the MoMA database. This candid photograph of him in his office shows the enormous volume of his daily intake--which is fully reflected in these essays.

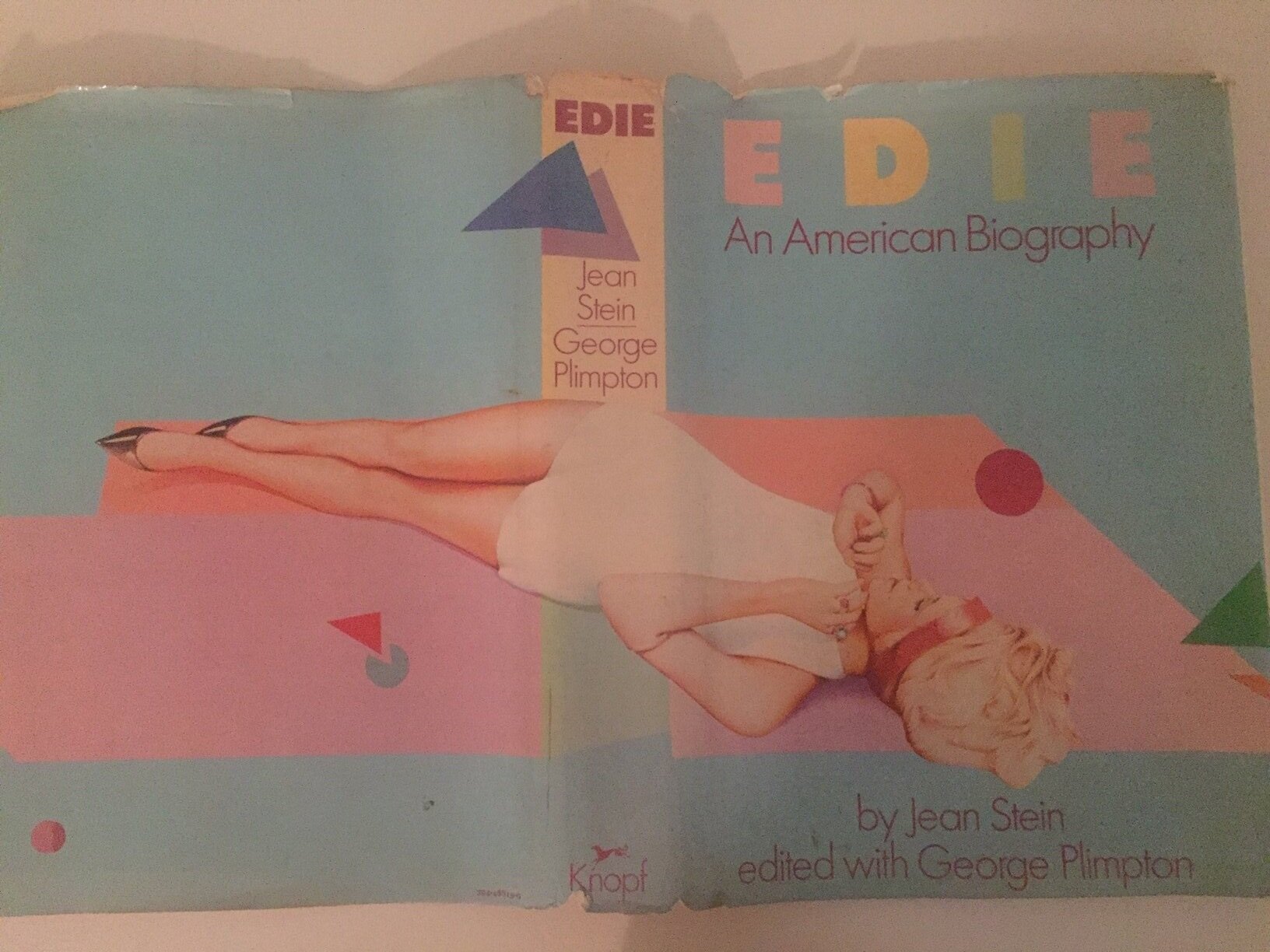

Remembering Jean Stein's illuminating bio of Edie Sedgwick

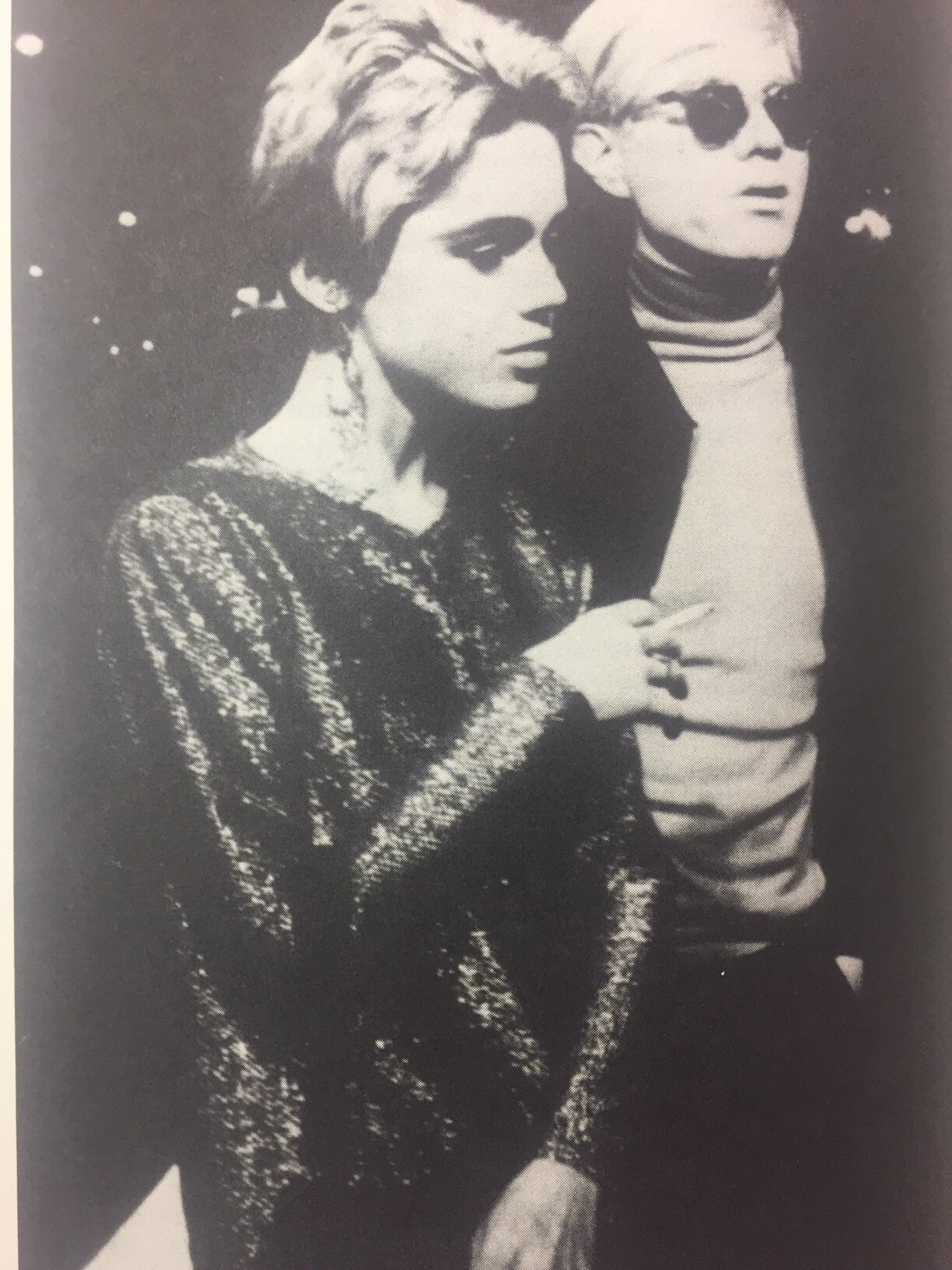

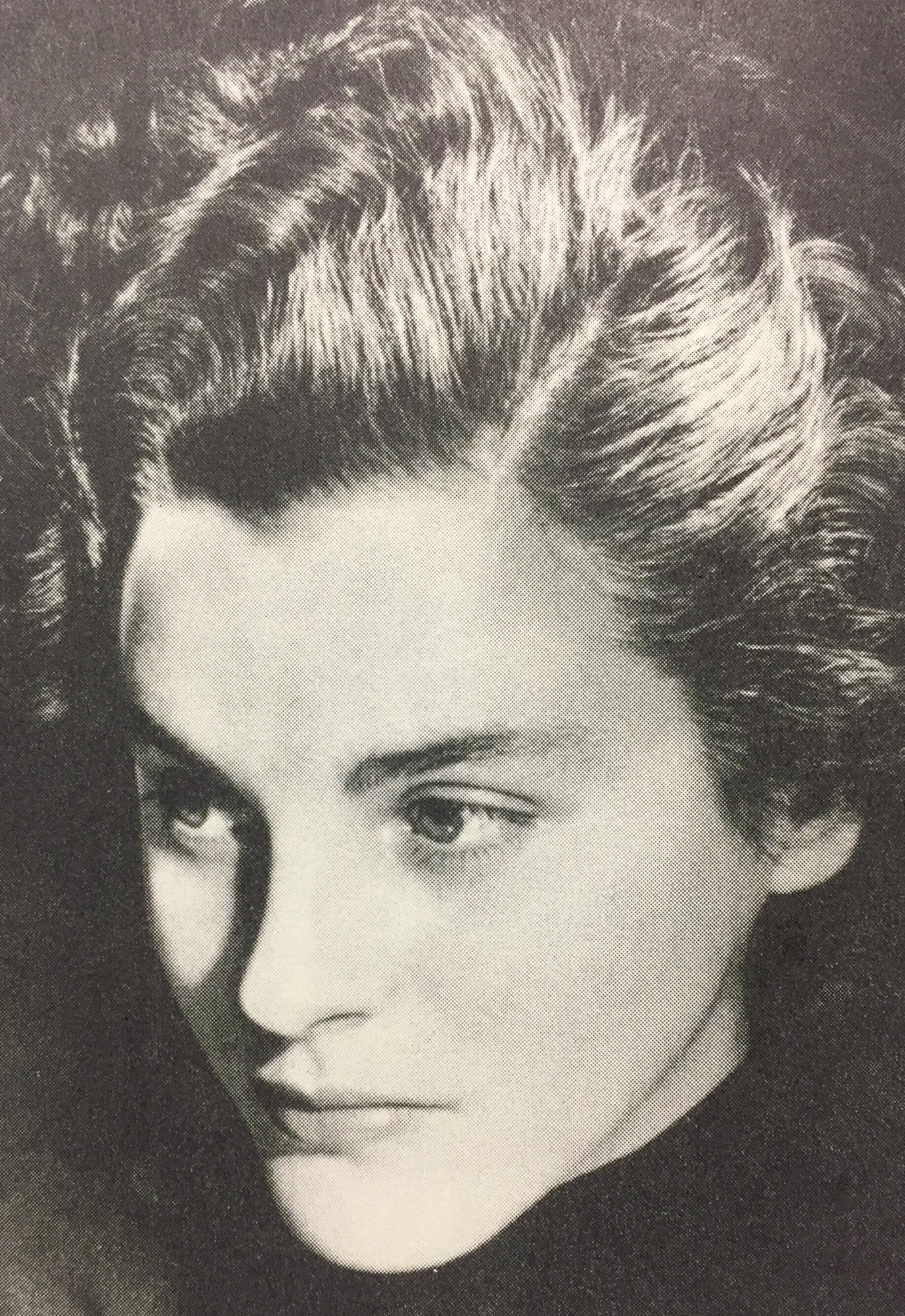

While I eagerly await my copy of Blake Gopnik’s new Warhol biography, I went back to Jean Stein’s riveting portrait of Edie Sedgwick and her world (old line WASP wealth and then the Factory), Edie, that appeared in 1982. Stein who was both of the world (a Hollywood daughter) and its excellent observer (via the Paris Review and George Plimpton, who edited this book) captured on-the-record oral histories that are still astounding in their you-are-theredness. Walter Hopps, curator, museum director, art dealer, nurterer of so many West Coast artists is on the record as are Truman Capote, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, denizens of the Factory, and of course, Warhol himself. Edie flamed brightly, erratically and died at the age of 28 of an overdose, joining a few of her other siblings who had not made it out of their twenties. Stein jumped from her window at the age of 83, which now casts an even more somber shade on this tragic tale.

Photo copyright by Nat Finkelstein, Used with permission of Nat Finkelstein Estate; Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgwick outside Lincoln Center

A spectacular Parisian vegetarian restaurant of the fifties

This is what a Parisian vegetarian restaurant looked like in 1954. La Saladiere--even the name was chic and prescient--was designed by Mathieu Matzot, now memorialized in a book by Patrick Favardin. How typically French to glam up even if you were just eating what then passed for vegetarian menu options: boiled veggies and various lettuces. Not surprisingly, the concept did not take hold with the French who were still under the thrall of boeuf bourguinon and the restaurant closed in a few years.

Images courtesy Matthieu Richard Gallery.

Mary McCarthy orphaned during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic

When lit star Mary McCarthy, future author of the incendiary The Group, about her post-Vassar years, was six years old, her uncle, the family's success story, left for Seattle in 1918 to oversee their move to Minneapolis after the onset of the Spanish flu pandemic. Her mother, brother, future actor Kevin and the two other siblings and her father were likely already sick. Instead of sheltering in place, they evacuated first to her grandmother's house since no hospital beds were available, then to a hotel. They boarded the train and one by one were carried off, ill or near death in the case of her parents. McCarthy became an 'orphan', and she recounted this defining experience in her Memories of a Catholic Girlhood, one of the first and best memoirs in which she doubts her own memory. It's something to read now when all of our memories will surely be compromised by this insidious, stealth Covid 19 disease. What is the truth?

Social Distancing As Practiced by the Existentialists

I always wondered why Simone de Beauvoir, author of The Second Sex which so roundly critics criticized the status quo between women and men, stayed involved with existentialist Jean Paul Sartre, even after he began an affair with her closest friend. Though the two did not believe in fidelity now I know why: they practiced social distancing!

A Race Against Time: one reporter's dogged pursuit of the Civil Rights murderers

Jerry Mitchell is the best kind of investigative journalist: his dogged and creative pursuit of his story-the Civil Rights assassinations of the sixties recounted in his new book Race Against Time— exposed murderers who had been hiding in plain sight. Michael Schwerner, along with James Chaney and Andrew Goodman became symbols of the bold crimes against the valiant who tried to help get out the vote in the south. That two were Jewish and one Black did not help their cause in racist Mississippi. Michael Schwerner's mom was our high school biology teacher. I often thought of her anguish and frustration as the Klansmen who had coldly plotted the murder were free for so long. Kudos to the plainspoken Mitchell for staying with it and helping to ferret them out.

Sam Wasson investigates the complex personalities that made Chinatown

Mourning the old Hollywood has become something of a cliché—yet there are some films that stand out for a kind of moviemaking in the seventies that no amount of Netflix or Amazon money can replicate: i.e. massive bets—many successful-- placed on talent without any assurance of box office returns. Chinatown was one of those adventures, not for the risk adverse. A producer, Robert Evans, whose eye for the sure thing was pegged to a sappy Love Story and the trilogy Godfathers; Robert Towne, a writer who struggled for years to get his story down; Roman Polanski, a Polish director who had made art films and Jack Nicholson, a star who held them together by sheer force of will and personality. All these come together in Sam Wasson’s granular, riveting history in his new book, The Big Goodbye. Wasson has them and close bystanders on the record. None remain untainted by cocaine and ego, but not enough to prevent Evans from digging his heels in and getting the movie done. Watch it again and be struck by how remarkably it holds up.

The Dolphin Letters: a study of writing and of love

Elizabeth Hardwick, Robert Lowell and Harriet Lowell, mid-1960s. Lowell was carrying this photo in his briefcase on the day he died in 1977. Photo courtesy FSG.

The recently published The Dolphin Letters, 1970-1979, those between writer Elizabeth Hardwick and her husband (then ex) poet Robert Lowell, and the small circle of intimates who were both their confidantes, close readers, and advisors (Mary McCarthy, Elizabeth Bishop, their publishers) are both profoundly moving and tragic and also uplifting in the way that only letters between such intelligent and self-aware people can be. Writer’s letters often function as alt-diaries, a way of learning what one thinks, but they also are uncommonly detailed and paint a portrait of a world less and less accessible in the age of internet.

Lowell and Hardwick were fine in between the many bouts of mania that hospitalized the poet over the years; the marriage of the southerner to the Boston Brahmin (though here revealed to have Jewish ancestors) was considered one of the pillars of the then very competitive, upper tier world of New York writers. Their daughter Harriet, at first depicted by Hardwick as pre-teen-y and difficult then comes into her own as she grows up in the shadow of Lowell’s coup de foudre—and subsequent marriage-- to Caroline Blackwood, a British beauty, heiress and writer who had already made other talented men (e.g.Lucian Freud, Bob Silvers) lose their heads. (See my recent post on the recent biography of Freud).

As the knowledge of the affair begun in England during a professorship Lowell takes, comes belatedly to Hardwick, she is devastated and lost. She writes to him, trying to hold onto him at first, and then slowly understanding the fullness of his attachment to this other compelling woman. We see her suffer deeply for a couple of years, and then gradually find her footing as an independent woman whose work—and daughter-- literally saves her life. Lowell reveals less as he keeps the details of his life with Blackwood from her for as long as he can but he is also stricken with guilt and confusion. Alongside the emotion are countless letters from Hardwick trying to grapple alone with their taxes and expenses and which takes over her life for extended periods. Friends McCarthy and Bishop—who are also close to Lowell--can only do so much to assuage her anguish.

Photo courtesy Harriet Lowell.

Compounding the torture is Lowell’s appropriation into his work, in particular his poem The Dolphin, of intimate details he culls directly from her letters. This fact is kept from her until it’s too late and the volume is published. The whole matter of how much writers are ‘allowed’ to capture from real life (this conversation generally around memoir today) is here fully fleshed out.

It brings round the subject of why publish these letters after all? Both Harriet Lowell and Blackwood’s children cooperated with this explosive volume—some would argue that sleeping dogs, children, wives and ex-wives should lie. For my part, I felt complicit at times in invading an intimacy to which I was not party, and yet anyone who has ever been rejected in love (and who hasn’t?) will feel a kinship with these two giants of literature who in the end had to sort through life as the rest of us must.

Lost Children Archive, the antidote to American Dirt

Valeria Luiselli though Mexican by birth is a global wanderer by upbringing and her empathy with childhood displacement is profound. Her story-or rather her multiple stories-tells of departures, journeys, searches: a family’s for a new life, a woman’s for an independent path, a man’s for fulfillment of an obsession, mother’s for their children, children for salvation in a new world, children for the attention of their own parents. Weaving these narratives in a novel which grows increasingly desperate and frightening in a scheme she rips both from the headlines of our border tragedies with Mexico and from Ovid, Virginia Woolf and Ezra Pound among others, she is deft stylistically and also heart wrenching. If you have time for one deep read in contrast to American Dirt, this should be it.

Afternoon of a Faun: James Lasdun writes MeToo as a Thriller

Spurred on by a review by Katy Waldman, I read James Lasdun’s slender but riveting novel Afternoon of a Faun. It was probably the frisson of the title drawing me in at first (Jerome Robbins ballet drawn from the same source is a particular favorite) but Lasdun has managed the hat trick of both taking a story ripped from the headlines and crafting a thriller around it. An unreliable protagonist, an unreliable narrator and an unreliable subject and #MeToo combine for some page-turning narrative delights and I could not put this down. It felt so good to be engaged in a novel, I am finding it a challenge to lose myself in fiction these days as it cuts so close to the bone. Highly recommended.