This is Maya Deren, the artist who transcended boundaries, friends with Dorothea Tanning and Max Ernst and Marcel Duchamp, but who very much went her own way. Born in the Ukraine, she lived in the US as a child and teenager when her parents emigrated, then went to Smith, NY and LA. She danced (for Katherine Dunham), she made films (which were very influential), she wrote, she was very much a part of the avant garde.

This still from her 1944 film, At Land, part of the Met's Surrealism Without Borders exhibition, captures some of her moxie. It was filmed in Amagansett. It's subtext drifts with the sand and sea around the notion of depaysement, or homelessness. She did not like to be lumped in with the Surrealists but she understood she shared some of their concerns around poetic and dream states.

Deren died at 44 in 1961 from a brain hemorrhage. She became addicted to the infamous Dr. Max Jacobson's speed and had more or less stopped eating.

Sedona In Tanning's Eyes

Dorothea Tanning and Max Ernst found in Sedona a place they had visited in 1943 a "camera sharp place where planetary upheaval had left its signature." Sedona, the place of reddish rocks and wide open spaces was so different from the European haunts of the two lovers.

She painted this Self Portrait in 1944 before they returned to live there. Tanning remembered, "I would undertake--dare would be a truer word--to paint the unpaintable....in the studio alone with my dream I would record it like a diary entry..."

Standing before the wide reaches of northern California this week I saw new growth under swathes of burned out forest— a small sign of renewal and hope. Planetary upheaval is alas ongoing.

Max Ernst, Francis Bacon and The Femme Fatale

In a Zoom offered by the Peggy Guggenheim collection this week on The Femme Fatale--first of three in a series on Myths, Muses and Models--this painting by Max Ernst was discussed, especially as an echo of a da Vinci at the Louvre, the Madonna and Saint Anne, and around its sexual implications (pre-Dorothea Tanning, first marriage). This is early Ernst, the Surrealist Ernst, before he came into his own, later more craggy style.

But to me, this work jumped out as a precursor to Francis Bacon. The erotic imagery felt so much like one of Bacon's central, torqued, tortured figures in a brilliant, empty background. I look forward to reading the new Bacon biography to see if he actually had the chance to see this work.

Max Ernst, The Kiss, 1927, Peggy Guggenheim Collection

Carrington on Madison: an exhibition of fantastical Surrealism

When you entered the recent Gallery Di Donna show of Surrealist artists, it was as if entering a museum. A companion exhibition of Leonora Carrington’s work at a Wendi Norris Gallery pop up makes Madison Avenue into a rare corridor of very special art instead of the latest overpriced shoe.

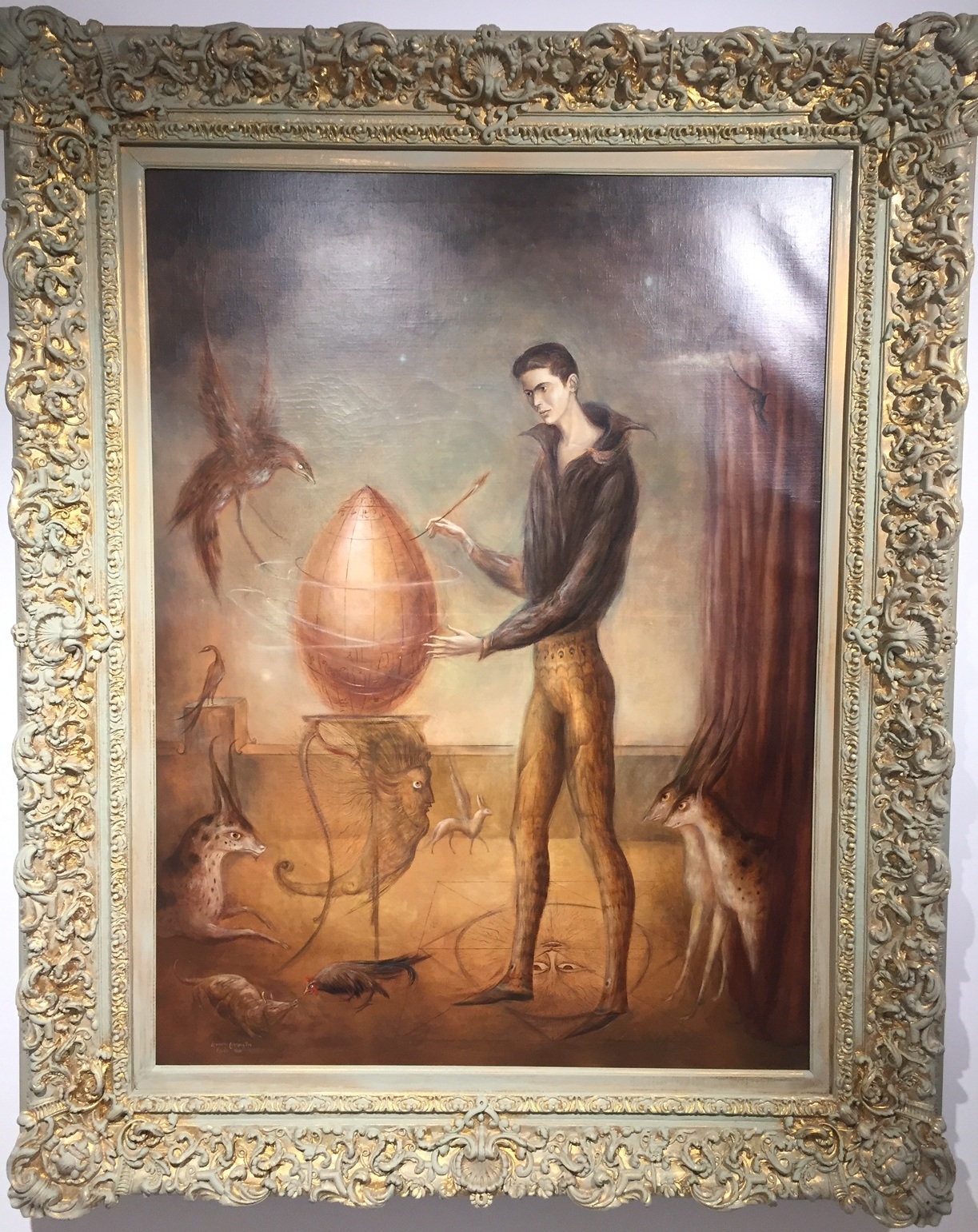

Carrington had a retrospective last year in Mexico but it did not travel to the US so this is a chance to see a selection of her work. Carrington was mad for Max Ernst, as was Dorothea Tanning (I had just seen her recent retrospective at the Tate, which also did not come to the US) Peggy Guggenheim, Gala Dali and assorted others. Carrington was not even 20 when she met the older artist but he was clearly catnip and they moved in together in Paris as part of the flourishing Surrealist circle. A later relationship with artist Remedios Varo in Mexico, her ultimate home, was also very productive. A lifetime of her work exploring nature, women, magic and domesticity replete with imagery of animals, humans and hybrids is both ethereal and powerful.

Dorothea Tanning opens eyes and doors at the Tate Modern

Like Warhol, Dorothea Tanning, the subject of a new retrospective at the Tate, toiled first in advertising when she came to New York. She had been deeply affected by the groundbreaking MoMA Surrealism/Dada show of 1936 and her ads for Macy’s and others reflected this new awareness of the ability to disassociate body parts and imagery.

She herself was selected by her future husband Max Ernst—then married to Peggy Guggenheim—for a show of women artists at Guggenheim’s Art of this Century gallery when she returned from a stay in Europe. (Was this the moment of the Ernst-Tanning coup de foudre? A year later they were together) Georgia O’Keefe refused to be relegated to this show of ‘women artists” but Tanning accepted. When next invited to participate however in a women-only show in the 70’s second wave of feminism, like many creative women who had already made their own way (Mary McCarthy, Lillian Hellman et al) Tanning was also finally a refusnik. ‘Women artists,” she said, “There is no such thing – or person. It’s just as much a contradiction in terms as “man artist” or “elephant artist”. You may be a woman and you may be an artist; but the one is a given and the other is you.’

She had by then grown into a bold, incisive, self-confident practitioner of painting, poetry, sculpture, costumes and set design.

"Just put yourself in my place, George, " she wrote after she had, in a labor of love, produced the costumes and sets for Balanchine’s new ballet Night Shadow, supported by Lincoln Kirstein, "and you would cry too." Tanning was passionate about ballet, but her production had an unfortunately short shelf life when a new production by the Monte Carlo ballet appeared just a few years later. "I really thought all this time that I had helped to make it a good work, and lots of other people thought so too. I was proud to have worked with you to make such a pretty ballet and I felt it was a real collaboration of all 3 of us. But I suppose it’s a very complicated story and I don’t understand very well how these things work."

Tanning went on to work on other ballets and had plans for many more, but was thwarted by lack of funding and the nature of the collaborative process which stymied her as a solo practitioner .

I wonder what Tanning would have made of the many women-only international shows organized this year in response to #MeToo. Ghetto or Gift? The concurrent counter narrative solo exhibitions—besides Tanning (Ernst), Lee Miller(Man Ray) and Gala Eluard (Dali)—who have finally been removed from the rolls of the ‘muses’-only, tell a more complete tale.

The exhibition runs from February 27 to June 9, 2019 at the Tate Modern. All images courtesy of the Tate.