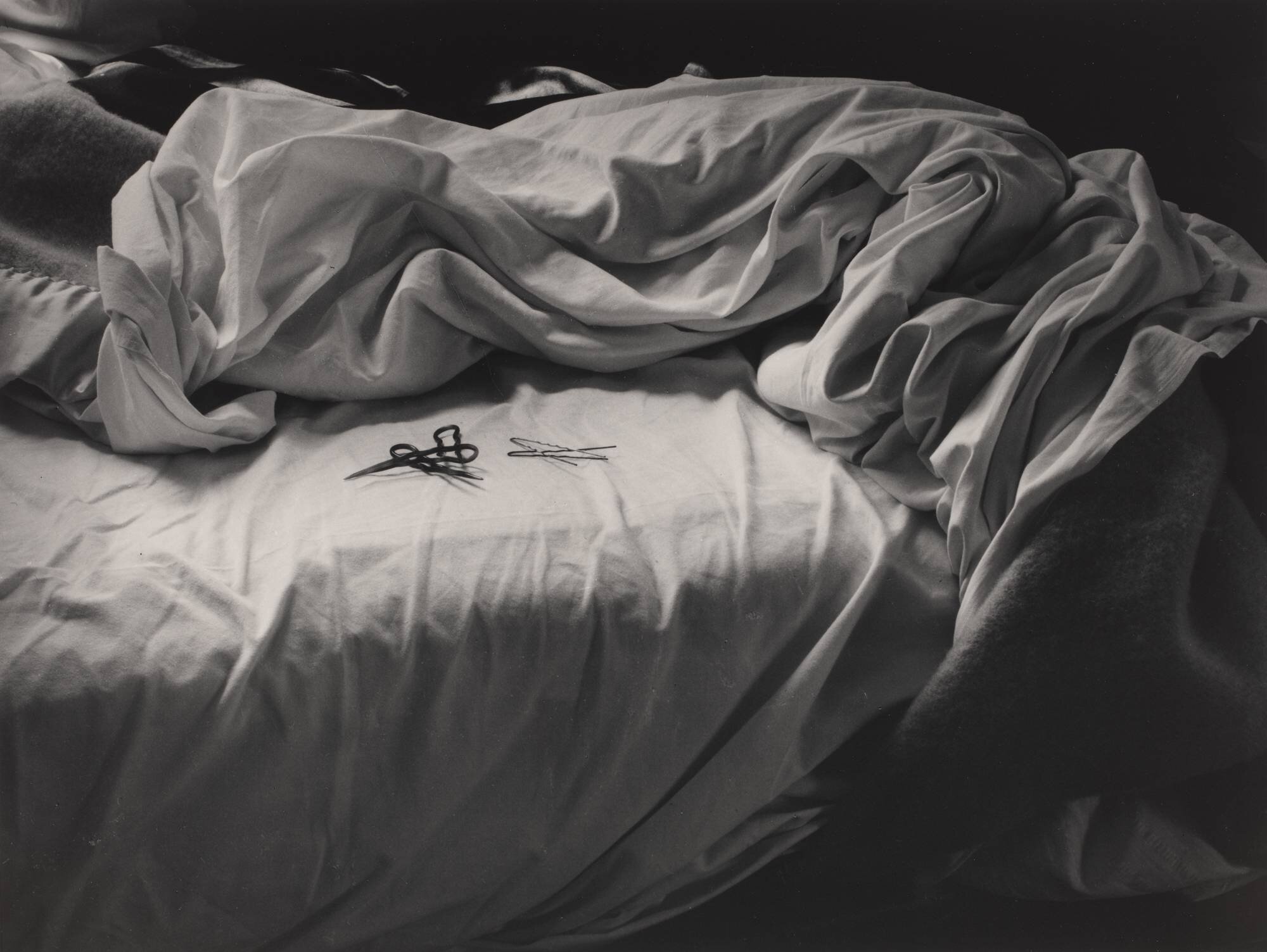

The Museum of Modern Art has acquired a stellar and also highly personal collection of photographs from the estate of Gayle Greenhill. Among many jewels is this image of an unmade bed by Imogen Cunningham. An unmade bed is a highly erotic image which calls to mind only two things: sex and sleep. Cunningham was not the only one to evoke this sensuality. Well before Tracey Emin, Eugene Delacroix painted what in my mind is one of the most evocative paintings of an unmade bed ever. His bed also summons the agonies of sleeplessness, night terrors and the tossing and turning bequeathed to us in times of fear and want.

Calder's Circus at the Whitney: A personal history

Alexander Calder, or Sandy as he was known to his many friends, was a tinkerer as well as one of the signature artists of the 20th century. A recent show of work side by side with Picasso at the Picasso Museum in Paris made his canonization complete. The first artist to make a genre out of mobiles and stabiles and subsequent author of monumental works had, however, a much different--even miniature--beginning.

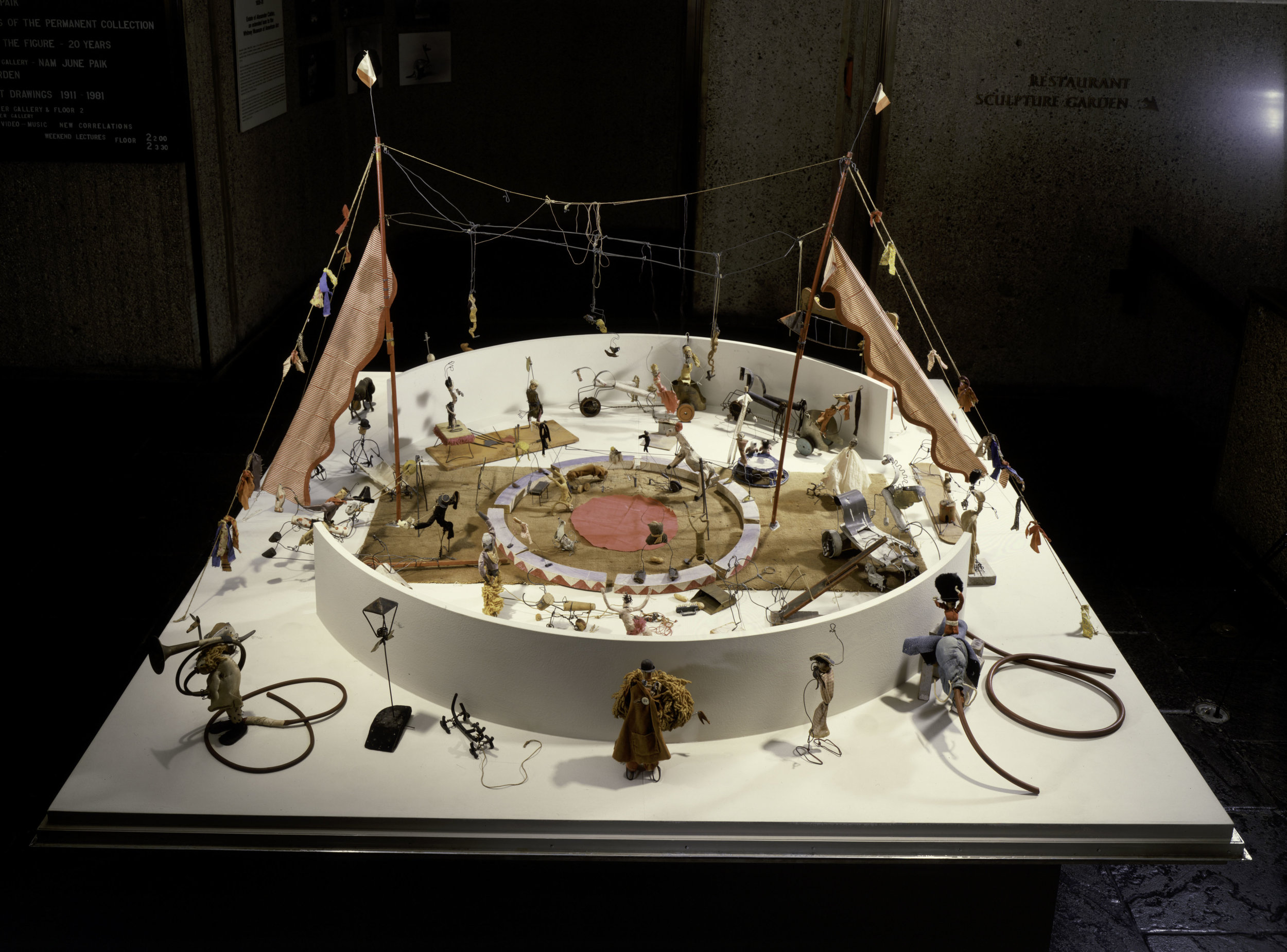

Calder’s Circus, now newly installed in the Whitney Museum, was actually the first expression of Calder’s playful artistic genius and came out of an assignment as an illustrator for the National Police Gazette at the age of 27. He was sent to the Ringling Bros Circus to sketch circus scenes and fell in love with the world of circus. The following year, in Paris, he created Calder’s Circus, an assemblage of miniature wire figures—walkers, clowns, trapeze artists, acrobats and animals and the like--that he packed into 5 trunks which he carried around with him and performed for lucky friends and avant garde circles. It gave him fame—and money to eat. It also began his exploration into the mechanics of wire work and balance he would need for his later, groundbreaking sculpture.

As an intern at the Museum of Modern Art, I was familiar with Calder’s work because MoMA had done a salute to him in 1970. MoMA’s collection was deep but the Whitney got the prize of the Circus. Designed by Marcel Breuer, the Whitney seemed to me a formidable, cold structure. Now I adore it, but then, it was imposing and I was intimidated, not fully understanding the Brutalist impulse.

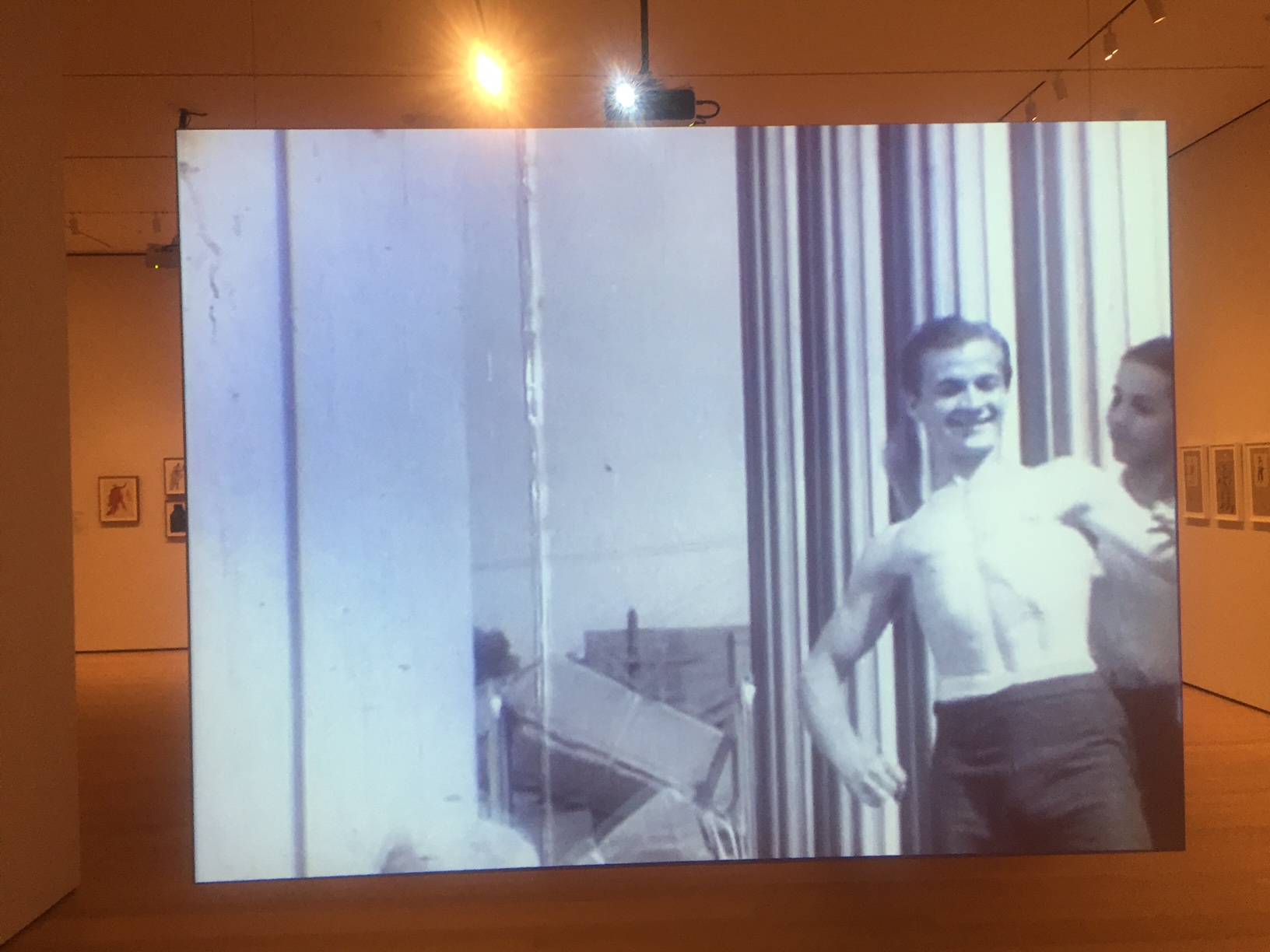

Somehow the circus was a light, magical oasis amidst the heavy concrete. A companion film showed how he manipulated his mini figures and I was enthralled—as most people still are today by the ingenuity and humor of the works.

Around the same time, my college boyfriend’s father died and we were invited to the Martha’s Vineyard home of his law partner who was a major Calder patron. It was the first time I was able to see Calder’s work in a light and airy domestic setting and in fact the first time I ever saw important art in someone’s house—right near the kitchen. My mother had been a skilled amateur painter, but this was something else entirely.

In 1976, Calder attended the opening of a major retrospective of his work at the Whitney. At that point, his circus was moved to the lobby. Somehow, I was invited to the opening and Calder himself was there in a wheel chair circumnavigating his earliest successful creation. He was kind enough to interact with viewers and even to autograph my invitation. It was not the first time I had seen a famous artist up close but it was certainly the first time that one felt he could have been a friend. Just a few weeks later he was dead.

Installation designed for the lobby of Whitney Museum of American Art and use in 1976 exhibition. Calder’s Universe (Oct. 14, 1976—Feb. 6, 1977). Designed by Art Clark, exhibition designer for Calder’s Universe. Photograph Jerry L. Thompson. Remained on view in the lobby from 1977-1997 approximately.

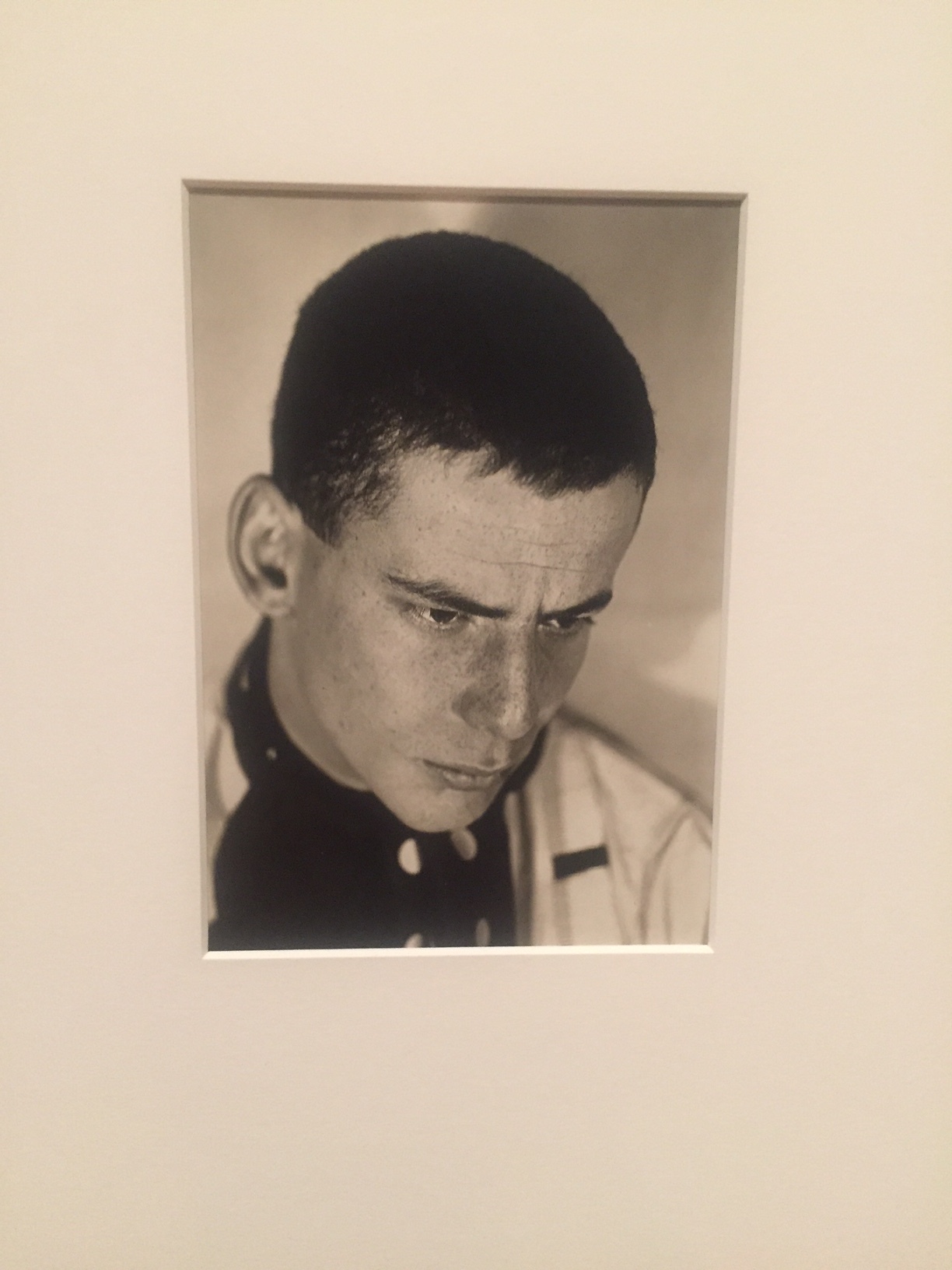

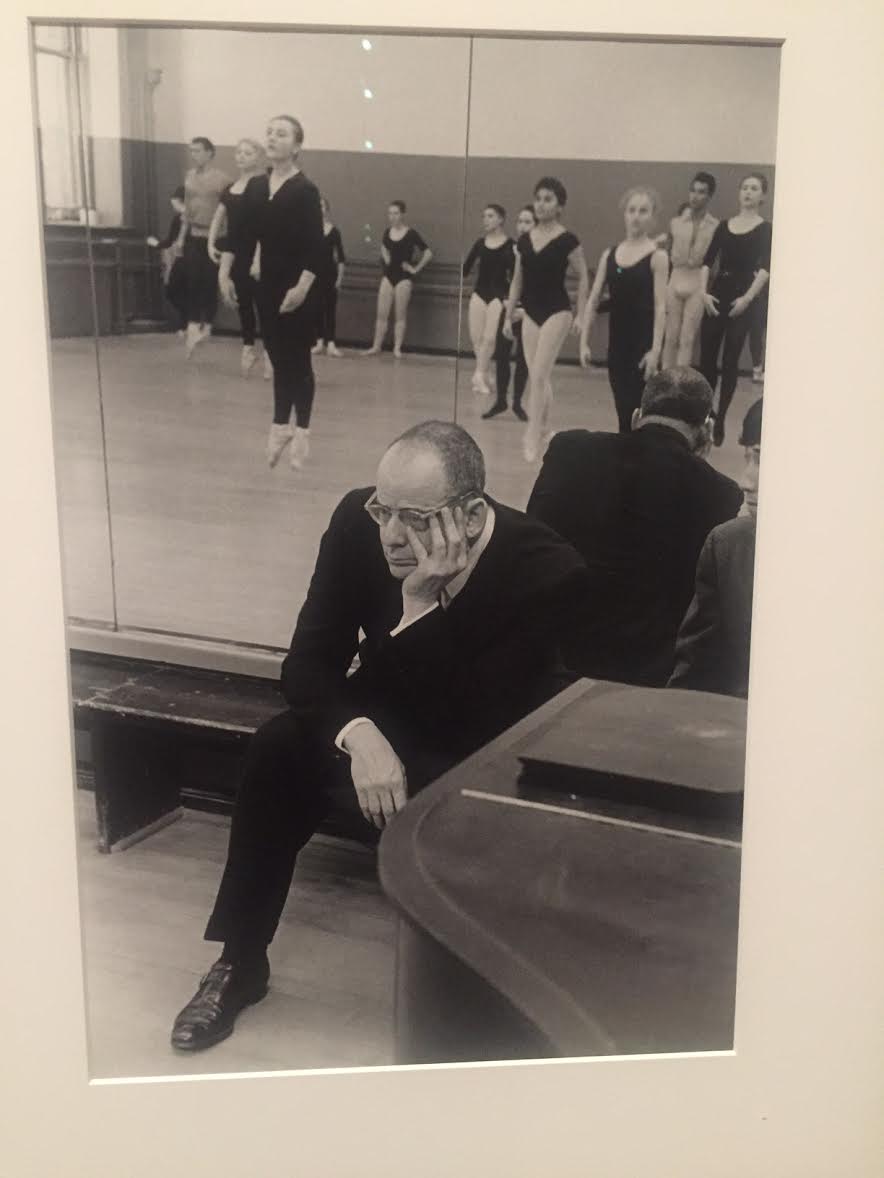

Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern

The Museum of Modern Art has exhumed its diverse archive of Lincoln Kirstein-iana in a new exhibition, Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern. We see his love for ballet, for art, for theater, for film, for photography, and for left-liberal causes.

I was in a class of 8 year olds at the school of American Ballet and it was Kirstein’s words in the brochure which had convinced my mother that a ballet career could, in the proper hands—e.g. Balanchine and his Russian Mesdames—be the equal of law or medicine.

He wrote he had his first coup de foudre for dance in the person of Tilly Losch who performed in Errante in a green satin evening dress with a twelve-foot train. A well-to-do, only semi-closeted Bostonian who became obsessed with ballet, Kirstein finally went to Europe as a young man, gathered his nerve, and asked Balanchine to open a school in America while at his fancy London hotel, far away from his family, surrounded instead by white-robed English beauties with plumes in their hair getting ready to be presented at Court.

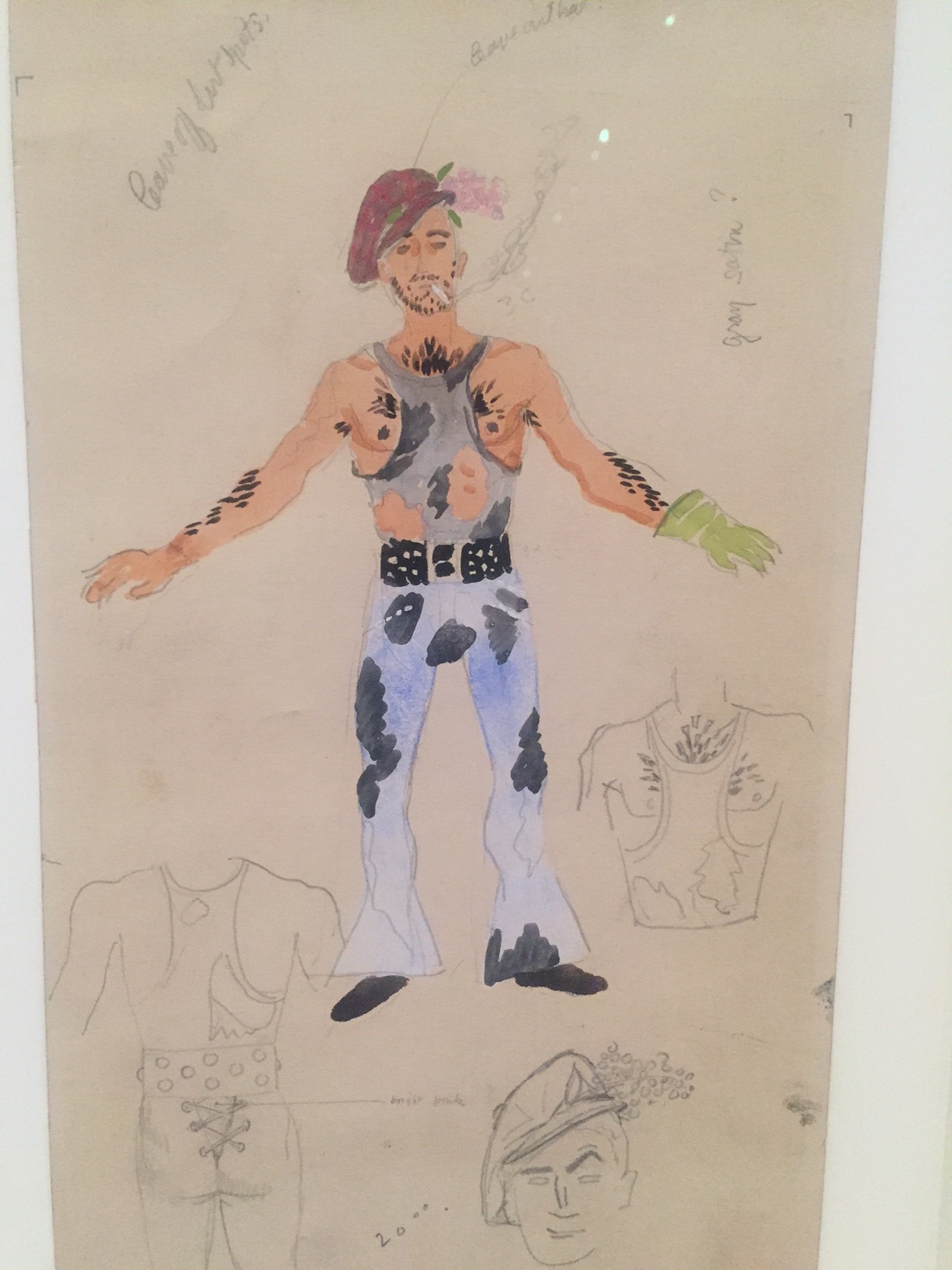

But MoMA is eager to show the man in full. Besides being an impresario, he was also a polymath, a renaissance man, a multi-disciplinary scholar, and a fierce advocate for the creations and artists he cared about. He seized upon MoMA not long after its opening as the perfect repository for his many enthusiasms. This is both the exhibition’s unifying theme and its challenge. Kirstein was not as gifted a talent spotter in every medium as he was a ballet agent. Even there, it was the collaboration with Balanchine which made his work in that discipline so important. His passions did not always allow for the best judgment, in fact then-Director Alfred Barr was sometimes at pains to rein him in. Kirstein pushed MoMA in directions they may not at first glance have anticipated including a Dance and Theater department, not long-lived—which now, however, seems prescient as performance has entered the curatorial mandate at MoMA and at many museums..

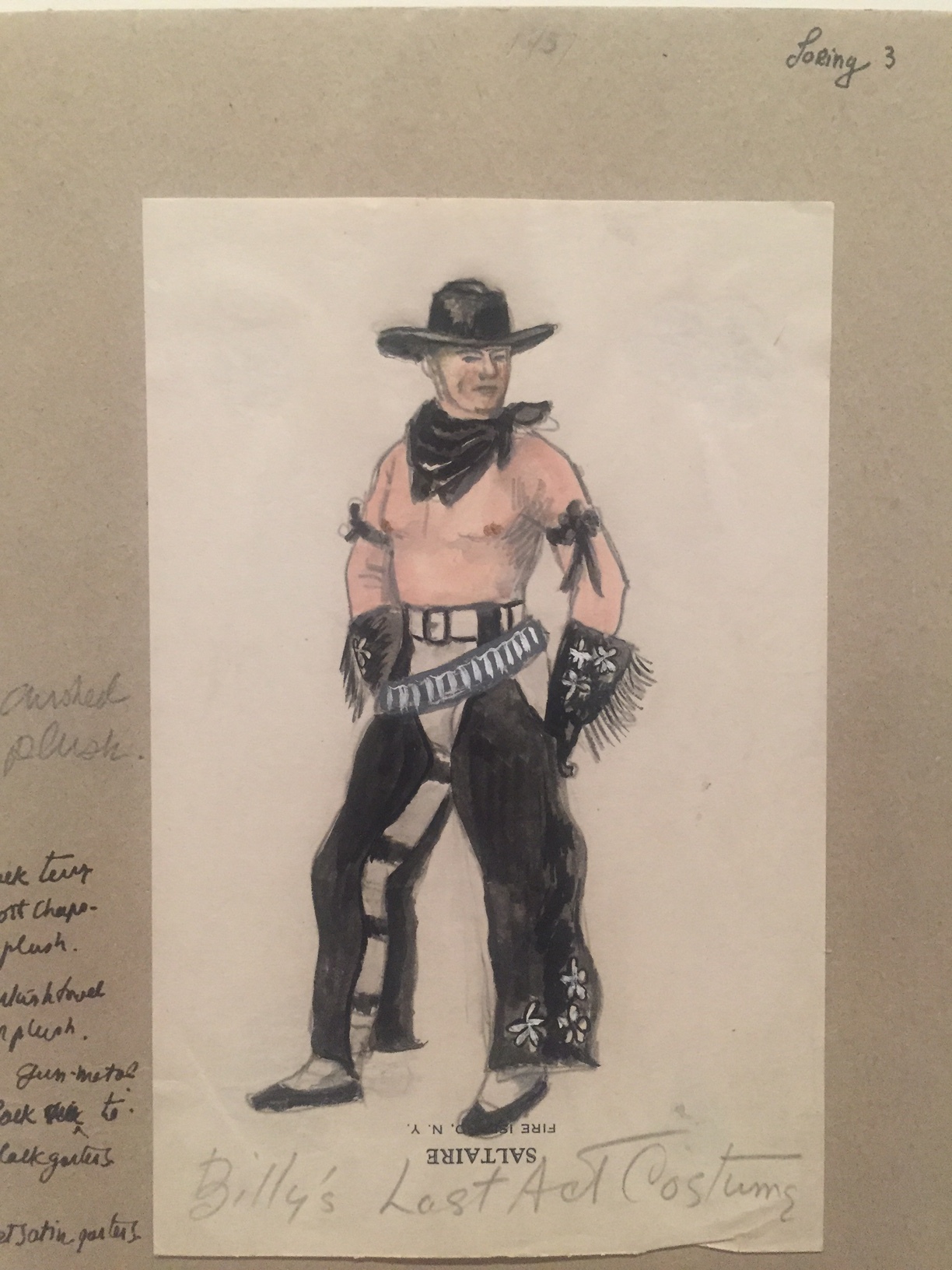

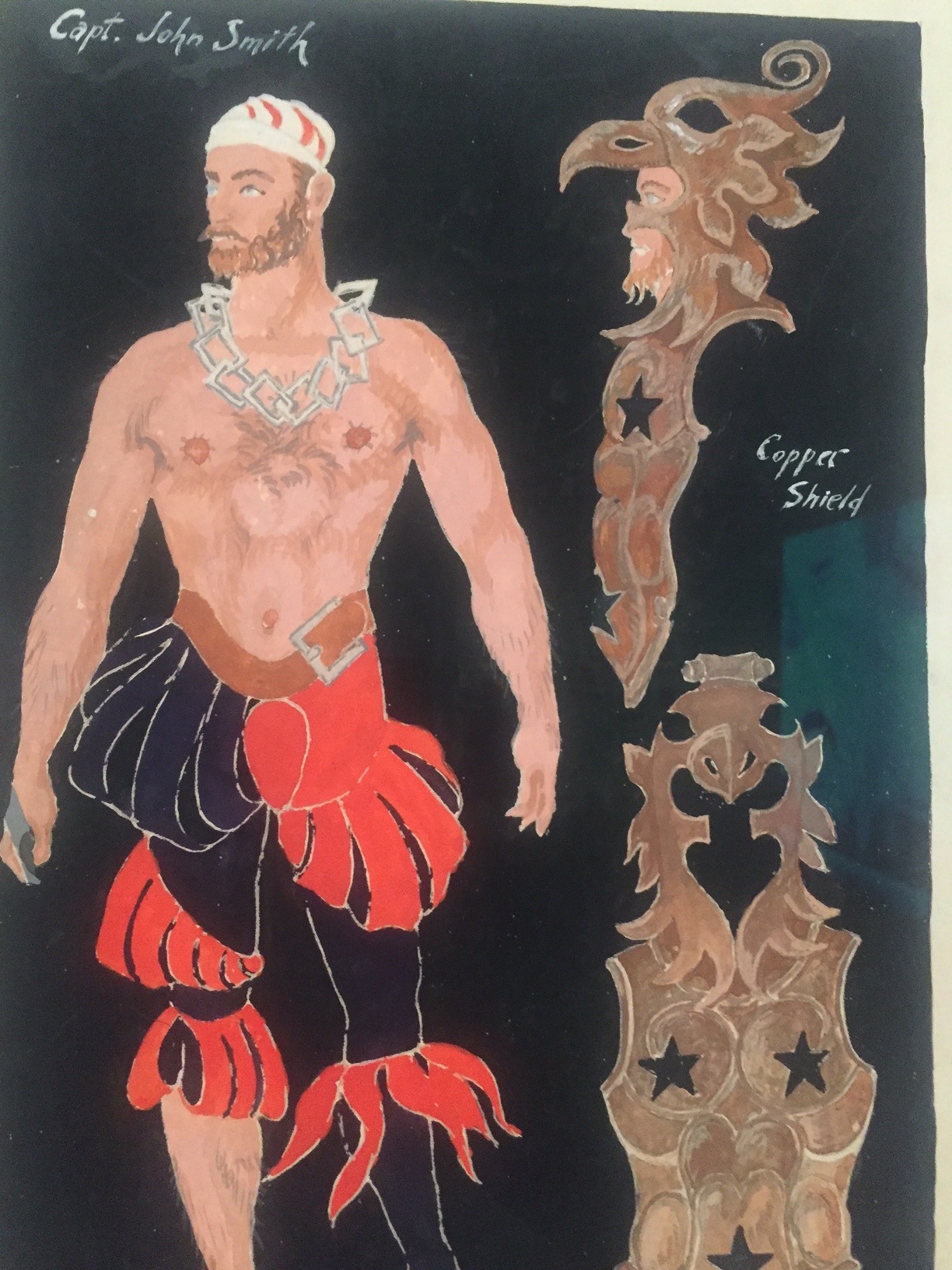

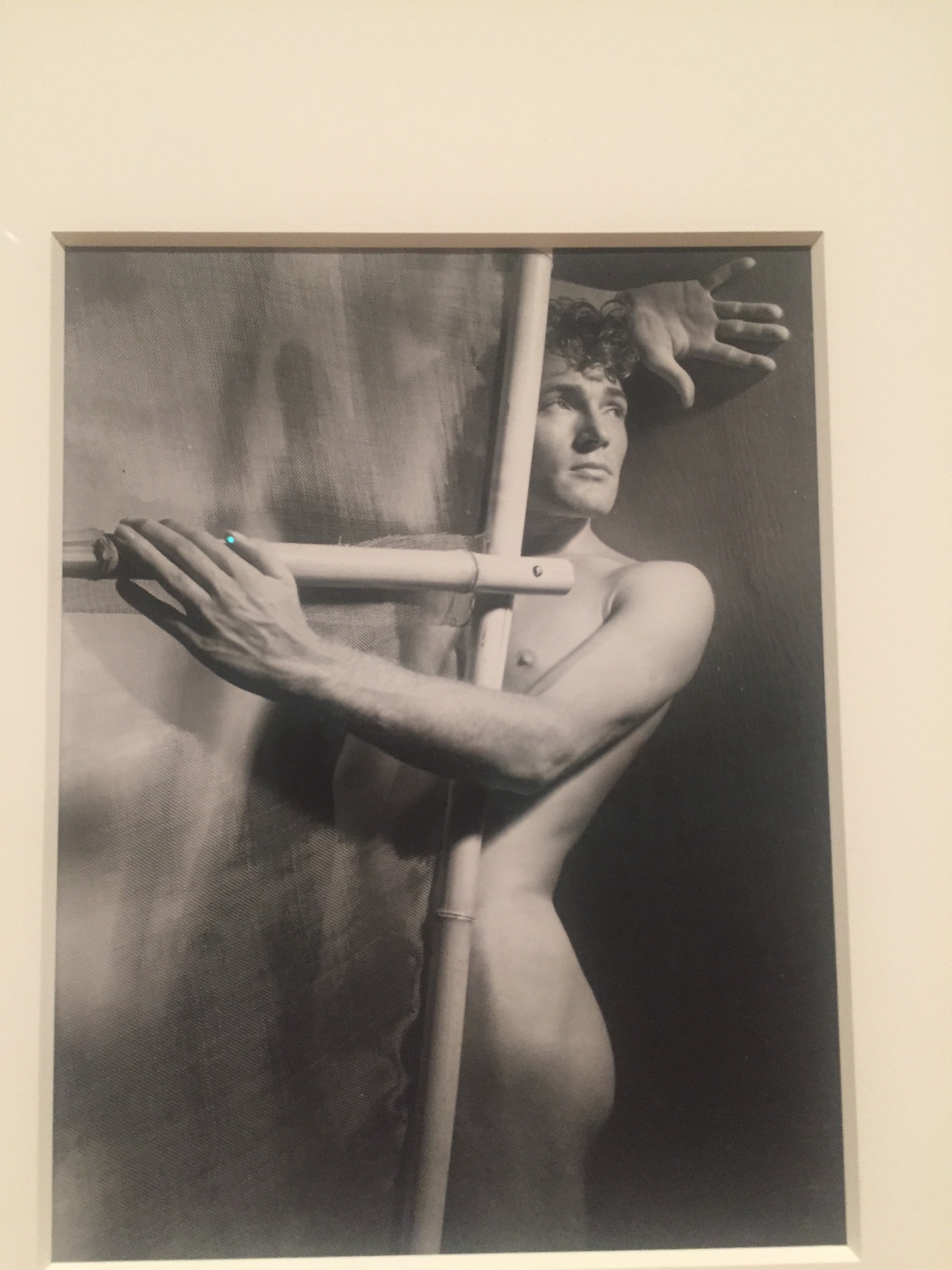

He made many subsequent donations including a large collection of George Platt Lynes beefcake. As the very interesting catalog and the many costumes and designs showing off buff male torsos makes plain,homosexual connections were the genesis of some of Kirstein’s most important collaborations. (As a young summer intern in the Publications Department at MoMA, I did not know for example that former department head Monroe Wheeler had once lived in a threesome with Lynes and writer Glenway Wescott. Kirstein himself had lived in a threesome with his wife Fidelma and dancer Jose Martinez. Etc.)

The discursive and lively exhibition, curated by Jodi Hauptman and Samantha Friedman, can feel a bit kitchen-sinky by the last gallery. But it accurately reflects a febrile mind from which sprang much curiosity ,encouragement and leadership—backed up by dollars. Would that the patrons of today had the foresight and stick-to-itive-ness of this brilliant man.

The exhibition runs from March 17 - June 15 at the Museum of Modern Art. MoMA is also collaborating with the NY City Ballet for performances in their atrium. A companion exhibition on Jerome Robbins is at the Cullman Performing Arts Library at Lincoln Center.

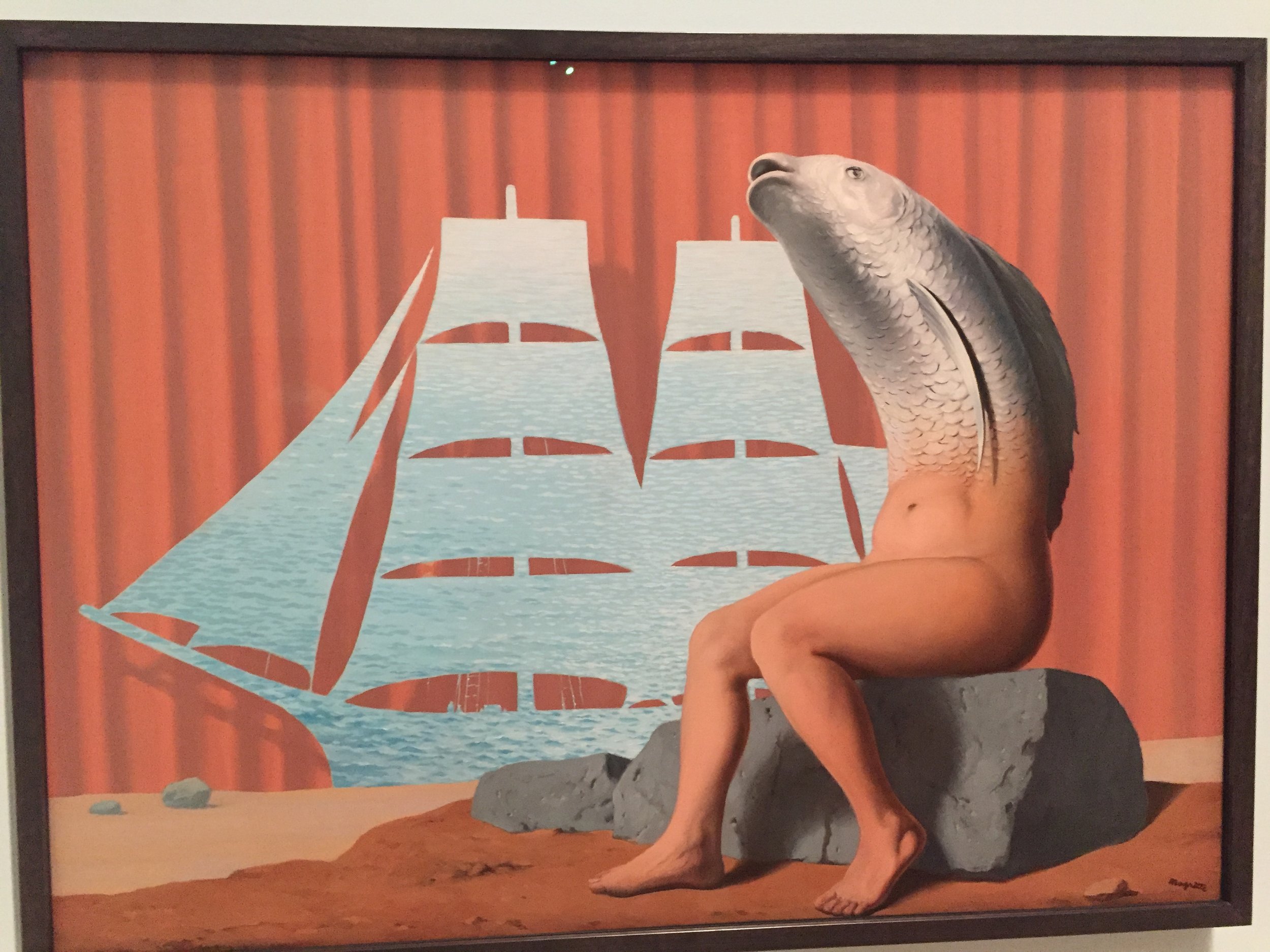

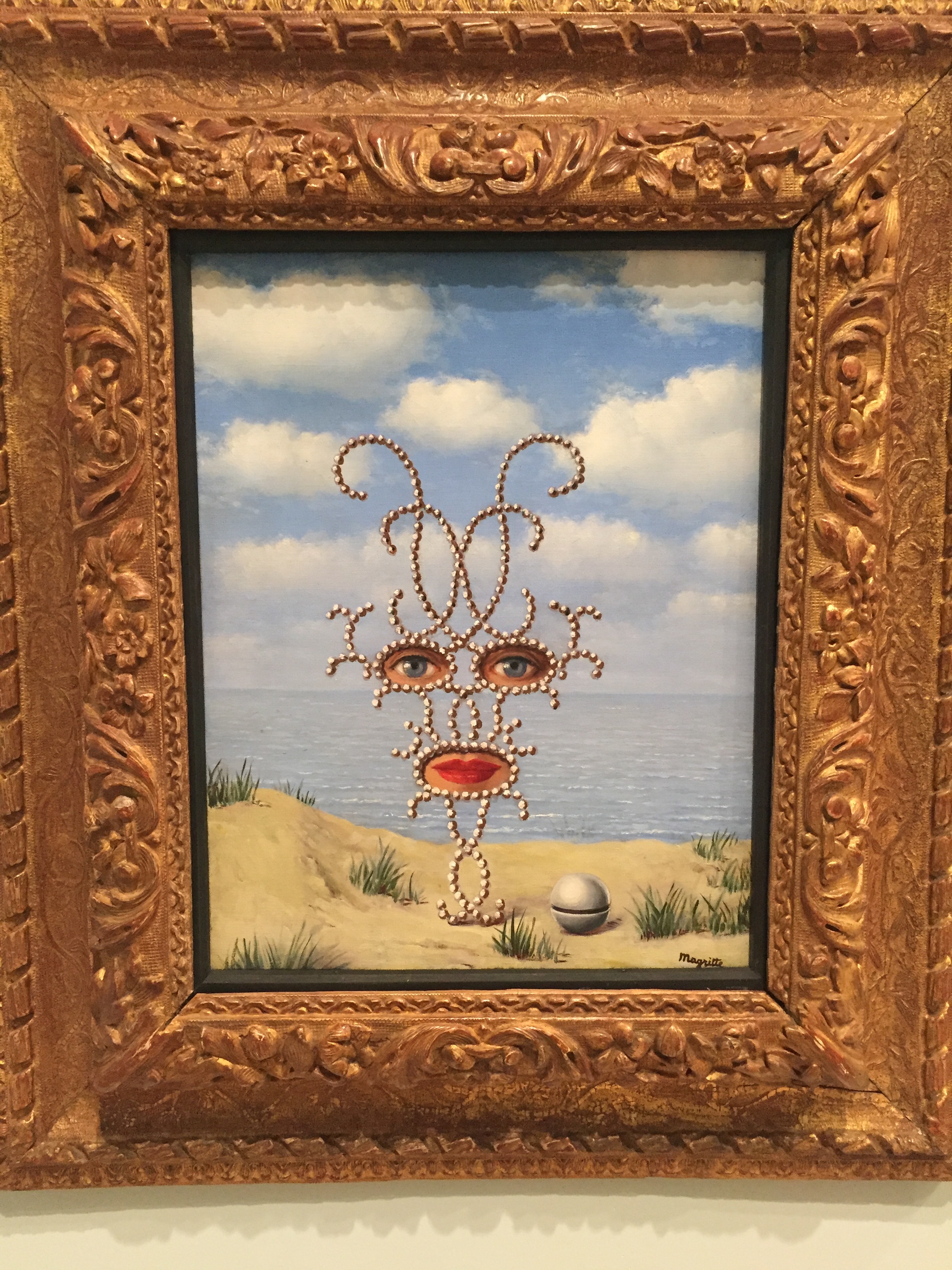

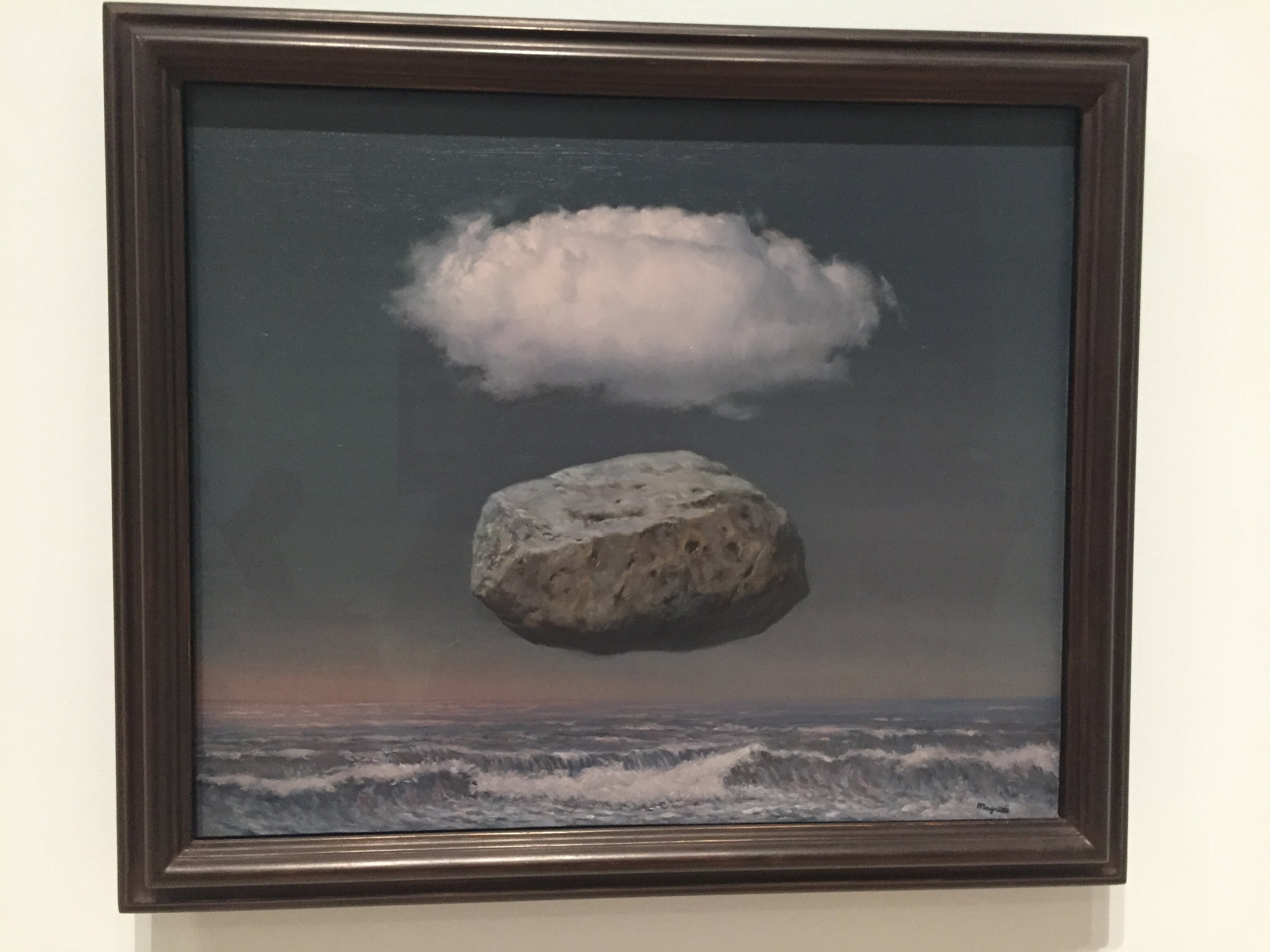

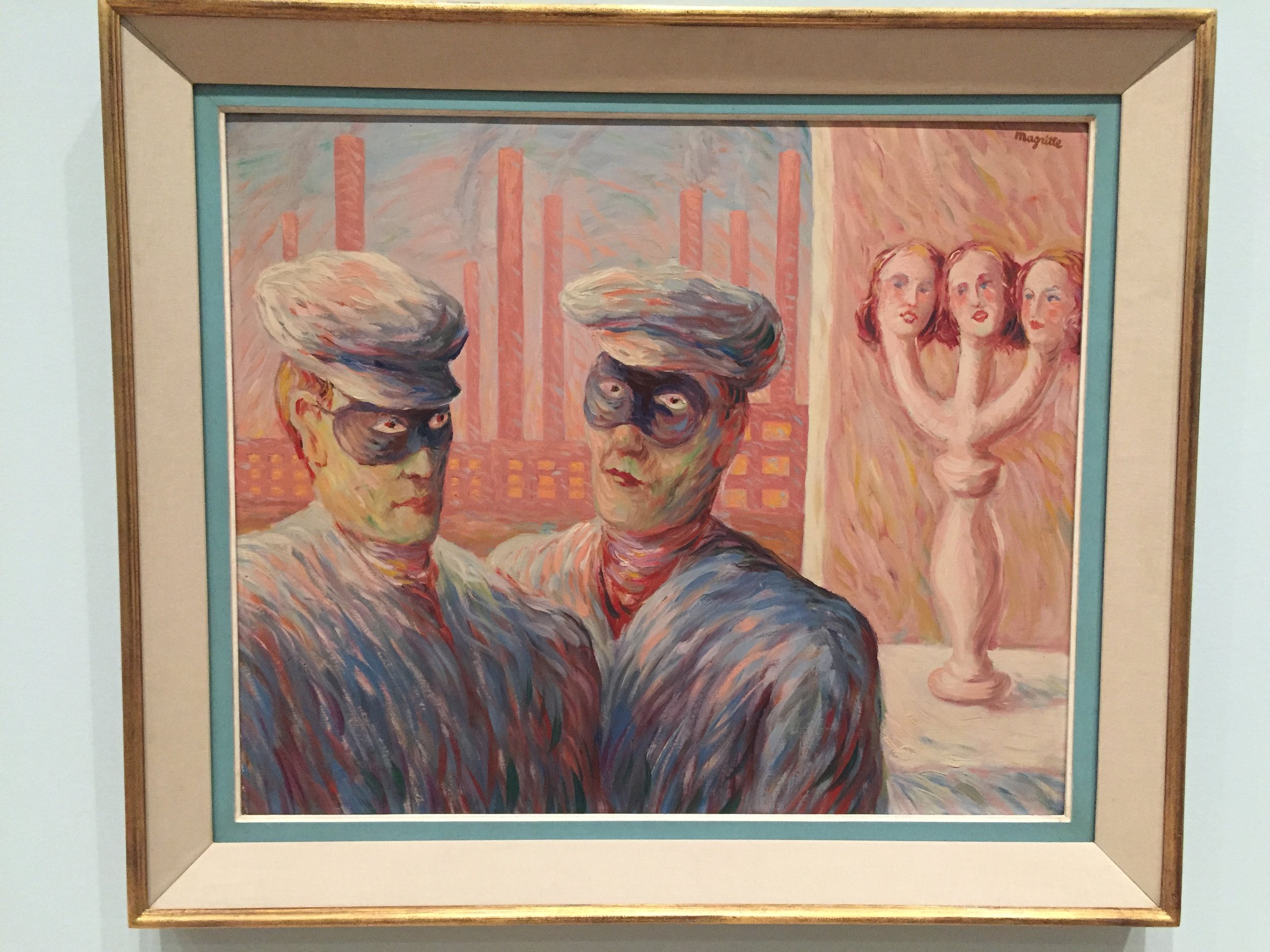

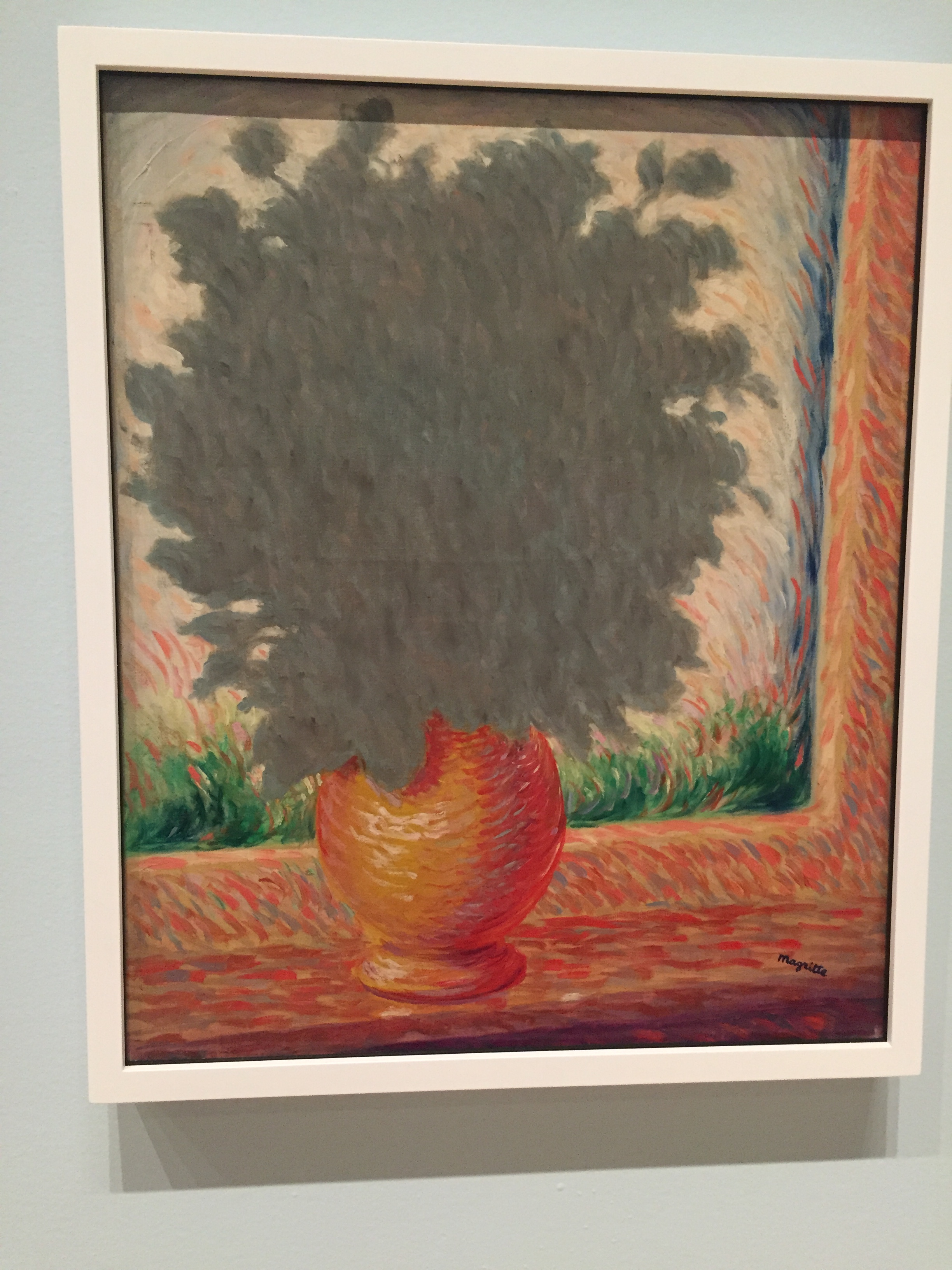

Magritte’s The Fifth Season, an exhibition of late work at SF MoMA has some surprises

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art has injected some new energy into the study of late Magritte and though these outliers in the oeuvre are not nearly as pleasing or inventive as those more familiar to us, some, especially those which refine or riff on earlier motifs (bowler hats, fire, mountains and stones) are lively and witty.

The late gouaches are especially nice-small and elegant and returning to the odd juxtapositions which made him not only a master of paint but also the bon mot. Magritte was in touch with the writers and poets of his time and infused his work with the allegories and allusions which preoccupied the Surrealists throughout his life. He believed "‘secret affinities’ existed between unlikely pairs of objects", reminds a wall label. “We know the bird in the cage,” he wrote, but “it is more interesting to replace the bird with a fish or a shoe.”

(The recent biography of the de Menils sheds some more light on this ‘late’ Magritte who appears to have been someone with a real sense of humor.)

The curators say he had largely left surrealism by this juncture. But he himself waffled when asked the question point blank. I appreciated their wall texts which split the difference. “When it comes to matters of the heart”, the curators write referring to image of a rose and sword, “Which is mightier?” They point out the multiplicity of layers in Magritte, his enclosing things in compartments to reveal the mysteries inside. This is the essence of surrealism.

Less successful are the works that hark back to the late Impressionists, or Fauvists and bad Renoir, and bring color and reality to subjects far from those we commonly associate him with—what is commonly called ‘sunlit surrealism’. It felt bumpy as if he himself had sought, during the Nazi regime, to hide his more daring, darker impulses. I suppose it was very contemporary of him to riff on the earlier artists, after all, it is one of the defining artistic motifs of our contemporary period, but for me they fell flat.

Magritte remains nevertheless close to my heart as you can see by my website cover image of his fish — a late gouache — wrapped in pearls. Another fish — Merman? Mermaid? — is part of the exhibition. He is a master at conjuring imagery of disparate things and bringing new dimension and meaning to each.

Also check out artist Ali Fitzgerald’s funny takes on some of Magritte’s iconic imagery.

The exhibition is up until October 26 and will not travel. A good excuse to visit SF where it is much cooler during the summer than the most of the rest of the US.