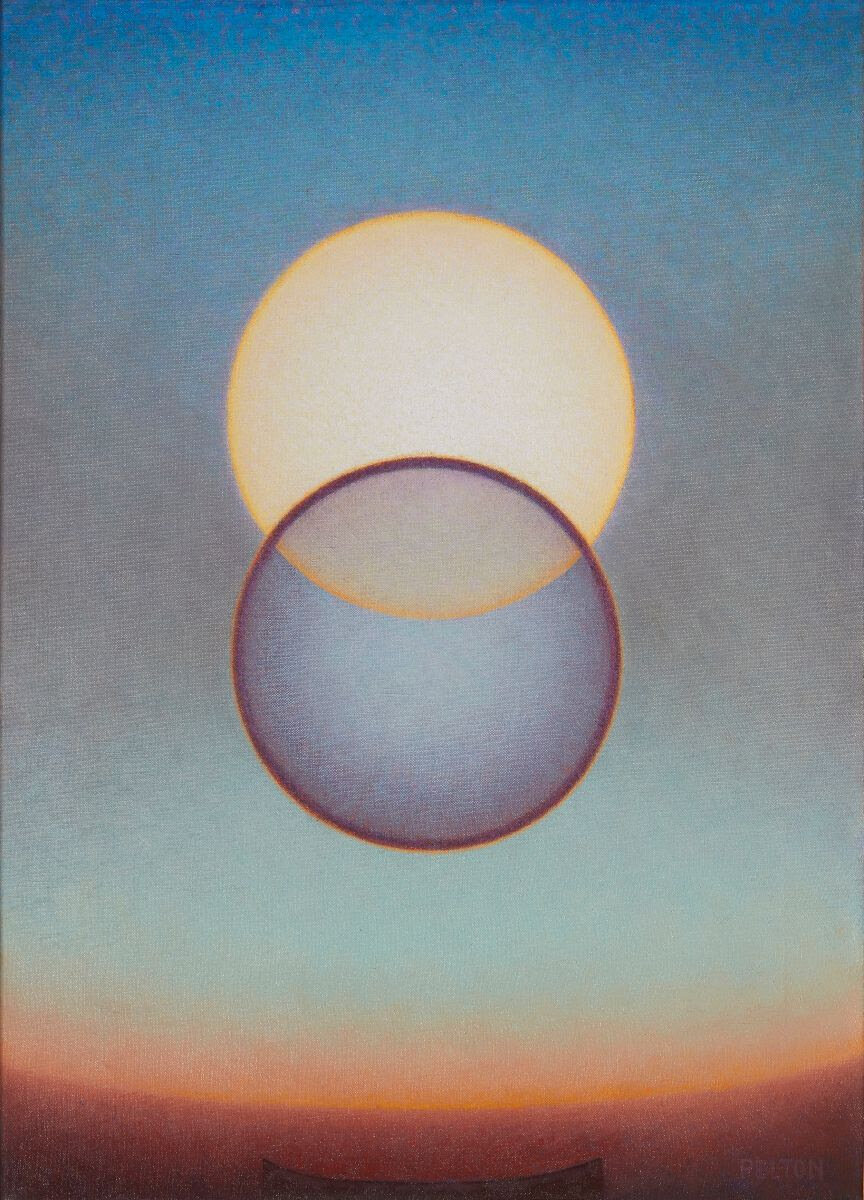

Agnes Pelton, cut from similar luminous cloth as Hilma Af Klint, arrives at the Whitney in a time when meditative, transcendental work is a tonic. Though often lumped in with O'Keeffe she rightfully belongs to Water Mill, NY and Cathedal City, CA. She believed in a divine principal and portrayed emblems of higher planes of consciousness which we could all use right now. She worked alone, and was not known in her lifetime Here two example of her gauzy symbolist work. Go the Whitney website for more Pelton images now that the museum is alas closed.

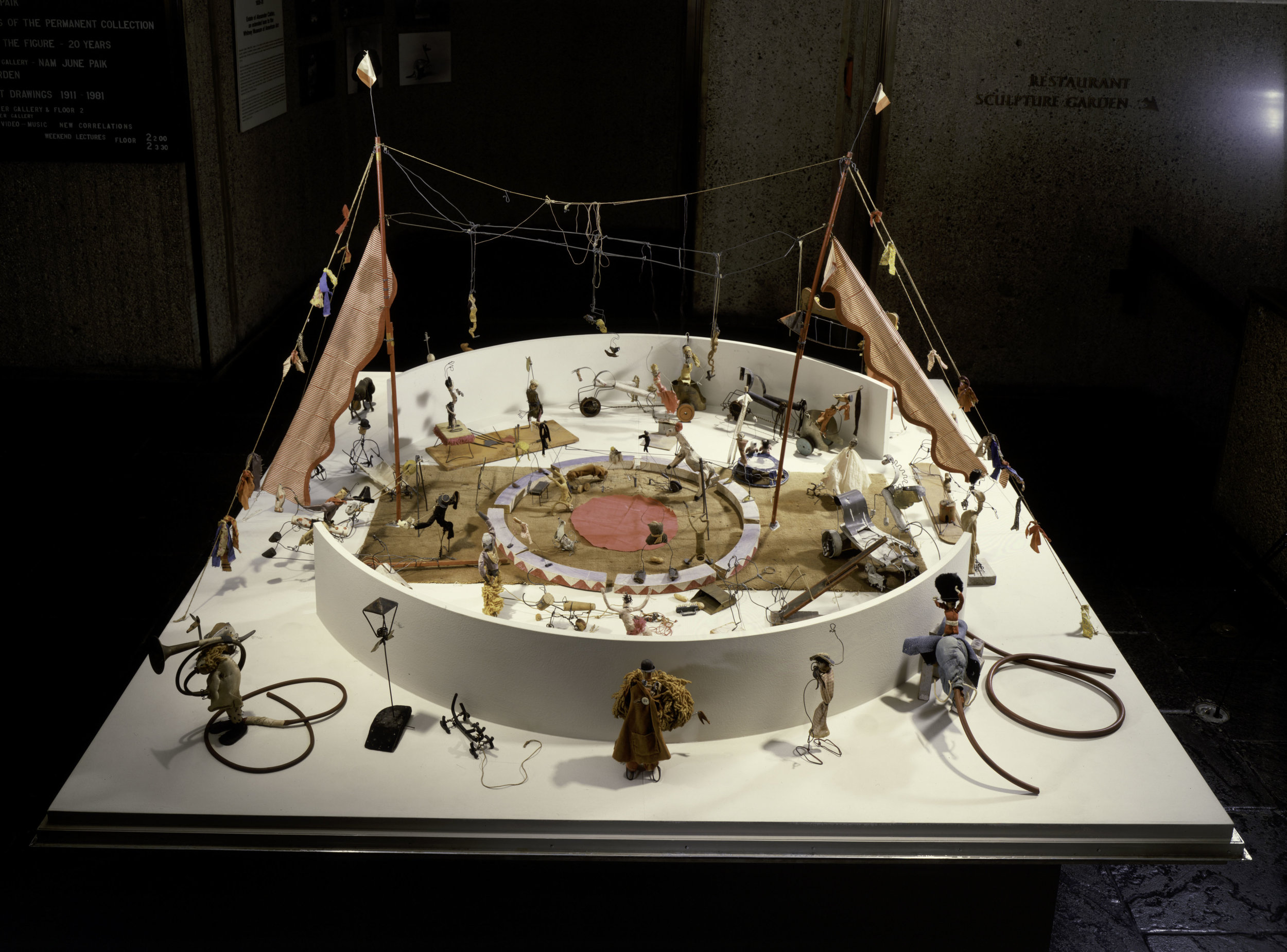

Calder's Circus at the Whitney: A personal history

Alexander Calder, or Sandy as he was known to his many friends, was a tinkerer as well as one of the signature artists of the 20th century. A recent show of work side by side with Picasso at the Picasso Museum in Paris made his canonization complete. The first artist to make a genre out of mobiles and stabiles and subsequent author of monumental works had, however, a much different--even miniature--beginning.

Calder’s Circus, now newly installed in the Whitney Museum, was actually the first expression of Calder’s playful artistic genius and came out of an assignment as an illustrator for the National Police Gazette at the age of 27. He was sent to the Ringling Bros Circus to sketch circus scenes and fell in love with the world of circus. The following year, in Paris, he created Calder’s Circus, an assemblage of miniature wire figures—walkers, clowns, trapeze artists, acrobats and animals and the like--that he packed into 5 trunks which he carried around with him and performed for lucky friends and avant garde circles. It gave him fame—and money to eat. It also began his exploration into the mechanics of wire work and balance he would need for his later, groundbreaking sculpture.

As an intern at the Museum of Modern Art, I was familiar with Calder’s work because MoMA had done a salute to him in 1970. MoMA’s collection was deep but the Whitney got the prize of the Circus. Designed by Marcel Breuer, the Whitney seemed to me a formidable, cold structure. Now I adore it, but then, it was imposing and I was intimidated, not fully understanding the Brutalist impulse.

Somehow the circus was a light, magical oasis amidst the heavy concrete. A companion film showed how he manipulated his mini figures and I was enthralled—as most people still are today by the ingenuity and humor of the works.

Around the same time, my college boyfriend’s father died and we were invited to the Martha’s Vineyard home of his law partner who was a major Calder patron. It was the first time I was able to see Calder’s work in a light and airy domestic setting and in fact the first time I ever saw important art in someone’s house—right near the kitchen. My mother had been a skilled amateur painter, but this was something else entirely.

In 1976, Calder attended the opening of a major retrospective of his work at the Whitney. At that point, his circus was moved to the lobby. Somehow, I was invited to the opening and Calder himself was there in a wheel chair circumnavigating his earliest successful creation. He was kind enough to interact with viewers and even to autograph my invitation. It was not the first time I had seen a famous artist up close but it was certainly the first time that one felt he could have been a friend. Just a few weeks later he was dead.

Installation designed for the lobby of Whitney Museum of American Art and use in 1976 exhibition. Calder’s Universe (Oct. 14, 1976—Feb. 6, 1977). Designed by Art Clark, exhibition designer for Calder’s Universe. Photograph Jerry L. Thompson. Remained on view in the lobby from 1977-1997 approximately.

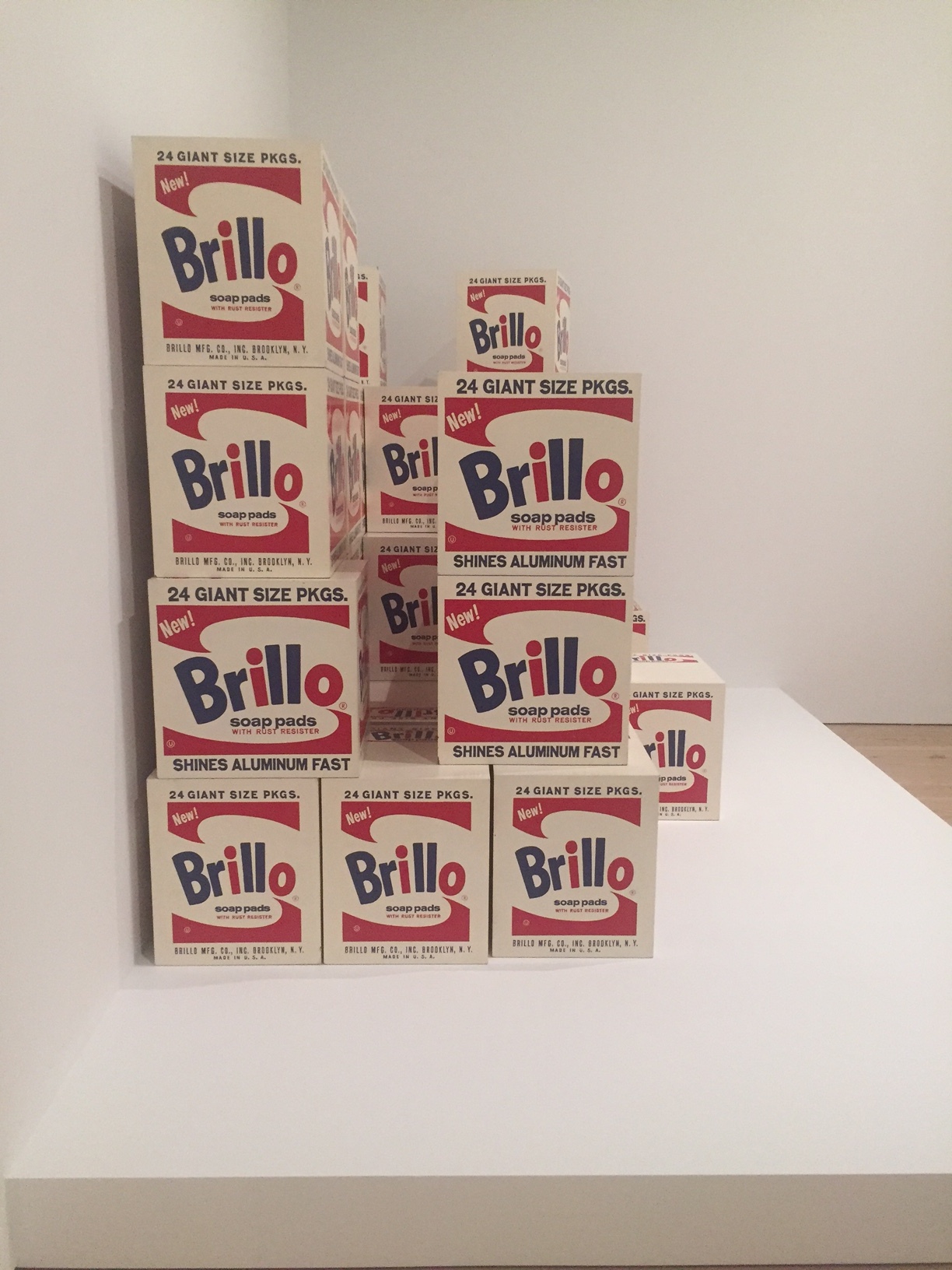

A new generation gets to meet Andy Warhol

You will get it all at the Whitney Warhol, as they say, A to B and Back again

You will get your Brillo boxes, your Coke bottles, your dollar bills, your Green Stamps, your Campbell’s soup cans, the Cow wallpaper, the Elvises, the raunchy films and video, and of course the gift shop filled with yummy, branded trinkets. Why the very word brand might first have been associated with Warhol the artist who made branding part of his artistic practice.

Like Picasso, the other great innovator of the 20th century, every successive generation discovers Warhol in its own way. The exhibition is dynamic and it’s going to feel completely contemporary to millennials. Selfies, brash colors, repetition as a motif, gay and transgender themes, news, fake news, record your conversations, (Warhol often referred to his Norelco Carry Corder as his ‘wife’), video. What’s not to like?

Warhol is also like Picasso in that you don’t need to say much more for people to have an image in their heads right away. This exhibition will help people to add to the Soup Can. If you are one who thinks of Warhol as precursor to artists like Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst, you will see how far above them he floats. The technical innovation alone is impressive.

What might also seem new-- though there have been smaller exhibitions relating to his early career as a graphic artist—are the charming drawings of Louis Quatorze golden slippers, Matisse-ean portraits, sweet illustrations for the many magazines and companies he worked for.

The Golden slippers are my favorites and precursors to the society and celeb portraits displayed in a large room on the first floor, the ones that buttered his bread and were a way into a magic kingdom which the shy, gay Pittsburgh boy from a Polish immigrant family had always held on high. The Golden slippers, like the later silk screen portraits are dedicated to his heroes and heroines: Diana Vreeland, Truman Capote, Mae West, Babe Paley, and the Bergdorf Goodman Shoe salon;)

I think however it’s better to start on Floor 5 because you see the genesis of these rather than having old ideas about Warhol reinforced.

He loved gold, and it was threaded through all his work. He loved camouflage. He stamped, stenciled, he cropped, he printed, the repetition functioning as a kind of punch in the gut. Oh yeah? Take that, and that and that again. Notice me, pay attention.

Curator Donna de Salvo who has toiled in the Warhol world for much of her adult life says Warhol asked the question in his Death and Destruction paintings: What is history? When do headlines become history? At first, he hand painted large scale copies of the front page. One of his first pieces is the NY Mirror 129 Die in jet,and the technique is breathtaking. Then he realized he could achieve very similar effects by silk screening these giant images.

Irving Blum’s story is that Warhol couldn’t make it out for the Ferus Gallery LA opening of 1963 so he instead sent stretchers and an uncut roll of printed canvas to the gallery and instructed Blum how to stretch and hang them around the perimeter of the gallery. Presto, change-o, Sell-o.

The blue self portrait from 1964, his first large self portrait made him a star in his own firmament of many stars though Ethel Scull got 36 reps and Warhol only 4. Warhol made selfies before there was such a term.

Warhol supposedly announced his retirement in 1965 and started doing cow wallpaper but really what he meant was that he wasn’t going to let painting confine him anymore but wanted to experiment in every medium. How contemporary does that sound? He collaborated with the Rolling Stones for the Sticky Fingers album cover ( I own one. Listen to the great songs on the album if you haven’t)

At first the perpetual outsider looking in and then an insider looking out, even when he became famous there was an ‘aw shucks’ quality about him. He was genuinely impressed with wealth and position. He loved Hollywood, and he loved rich Europeans too but he also admired his fellow creatives.

The exhibition makes clear Warhol was not androgynous. Drawings and early works from the 50s depict his gay friends and lovers and are evidence this was a man for whom sex was a driving passion.

He was also one of the first artists to conceive of exhibitions as immersive experiences interrelating with their environments. This is nimbly illustrated by a series of photos of him vacuuming the space before installing his work at the Finch College Art Museum.

Yes, like many many others, I met and exchanged sentences with Andy Warhol a few times. I can say that going to the Factory for me (as a hanger on to a bevy of European heiresses) felt like going to Studio 54. I was scared of the mylar and the druggie corners and the post-Edie ennui. As the hands of the Factory became more pronounced and Warhol moved to film and other interests, he did a series of shadow paintings (installed now at Dia). Camouflage came back. Maybe just another version of the white wig he always wore to make him disappear.

But de Salvo makes the case that the work of the 70s and 80s was every bit as revolutionary as the 60s, though at the time, this work was in eclipse and people felt he had homogenized himself, “that the work had lost its vitality”. She is convincing only up to a point. It’s no secret—and understandable-- that after he was shot, a certain fearlessness seems to have disappeared along with innovation.

When the headline appeared on the front page of the Daily News it was as if Warhol himself had painted it—life imitates art, you bet.

Warhol died at 58 later, of surgical complications. Would he have made more groundbreaking work? De Salvo thinks most certainly yes.

Attention younger folks: if you see the new Studio 54 documentary , and this exhibition, and read Truman Capote and Jean Stein’s still marvelous book on Edie Sedgwick, you will feel the strands of the 60s and 70s tied up quite neatly. Everything about 2018 was there in 1968 except the internet which I think Warhol would have adored. Once again, The Price of Everything seems old news when you see that Warhol was onto the art vs commerce thing so very long ago.

De Salvo boils it down to this thematic essence: innovation vs conformity. Obama vs Trump, I mean I could go on and on. As a wall label explains, ‘the sizzle, not the steak”.