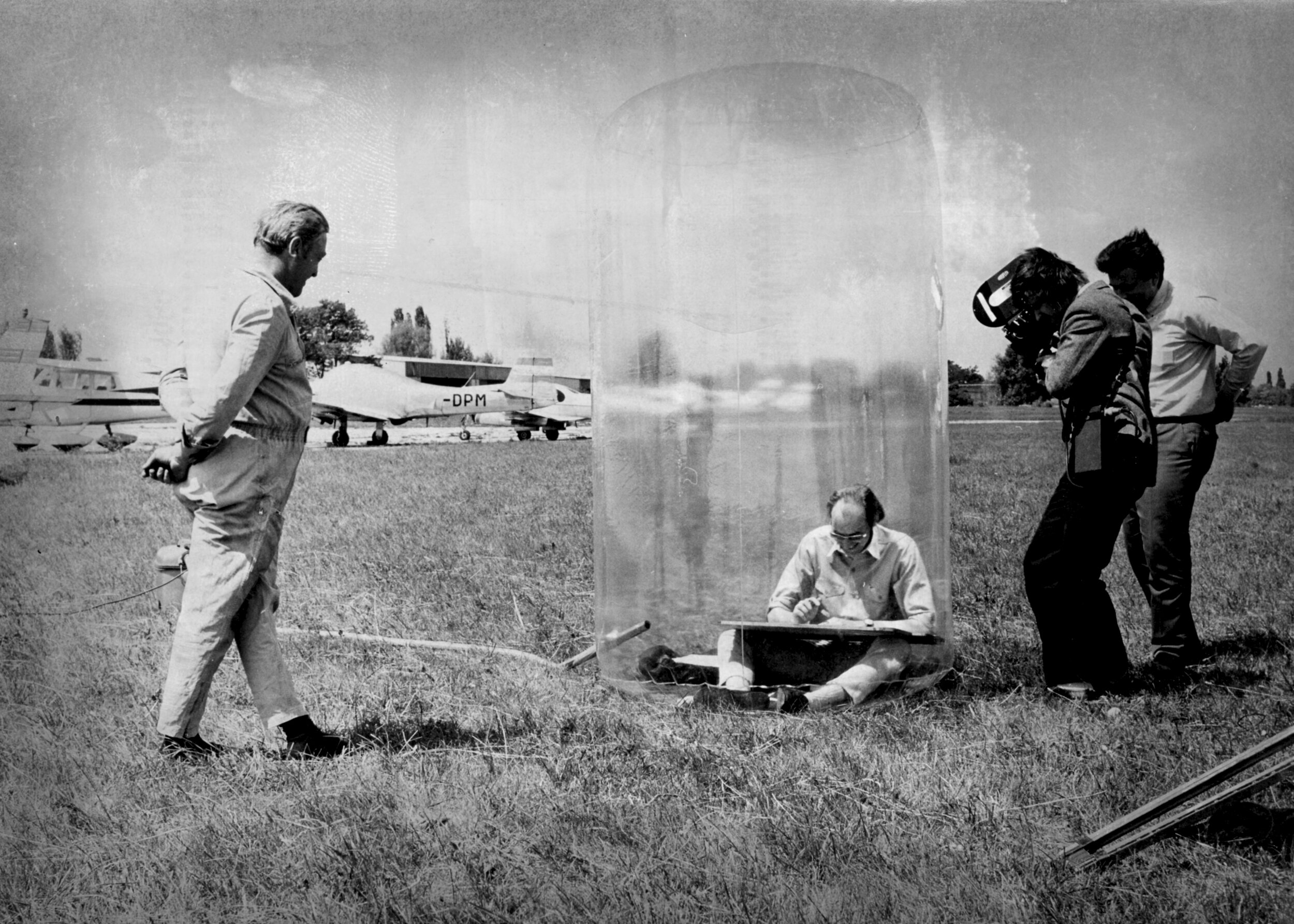

In a career filled with cliffhangers and high drama, there was likely no moment more urgent for the polymath architect Lina Bo Bardi than the one captured by a photographer in 1967 (above). In her on-site design office under the grand span of the Museum of Art of São Paulo (MASP), her riskiest architectural scheme to date, the restive, Italian-born Bo Bardi, was, for a rare moment, stationary. The project in her adopted homeland had been riven with years of frustrating political setbacks and engineering fixes to her radical design, and now she was racing to meet the 1968 inauguration by Queen Elizabeth. Beside Bo Bardi, Van Gogh’s The Student (The Postman’s Son, Gamin au Képi) was encased in a prototype of her innovative freestanding glass-easel display system, which allowed viewers to circle paintings as if meeting a friend. Behind her stood construction workers, a symbol of the premium she placed on architects acting as instruments of and for the “people”—to whose creativity and needs she was devoted—and not gods who put their designs and egos first.

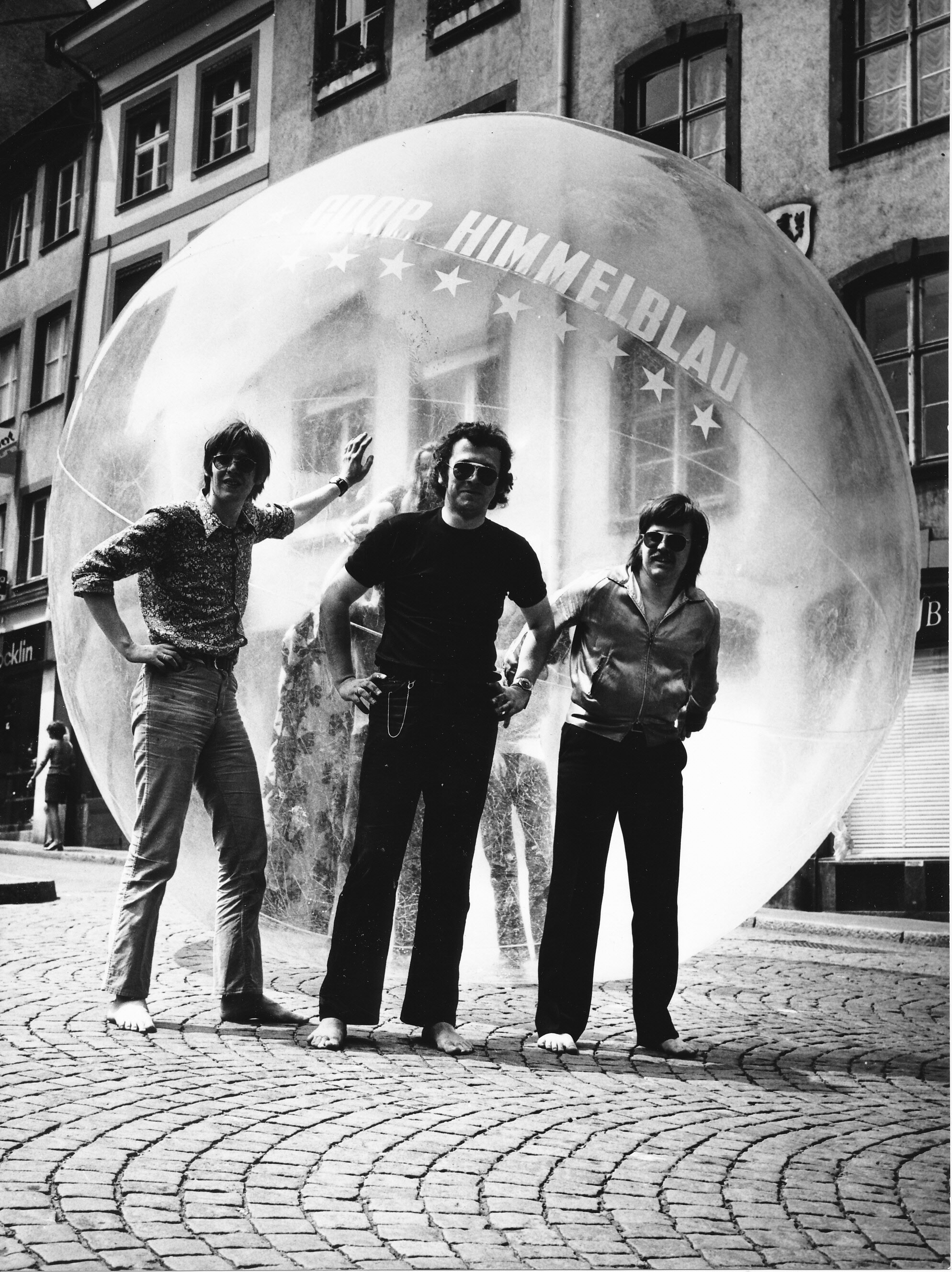

Recently the subject of “Habitat,” a three-venue career retrospective, and a show of drawings at the Carnegie Museum, all cut short by the coronavirus, Bo Bardi’s work is included in newly reopened exhibitions at the Design Museum Gent, in Belgium, and the Vitra Museum, in Germany. Bo Bardi, who died in 1992, has arrived at the pinnacle of international recognition as much for her diverse body of work as for the original way she went about it.

High-strung, alternately adored by and alienated from her collaborators, Bo Bardi craved attention but struggled for years before receiving any significant commissions. In the interim, she poured her considerable energies into editorial and educational projects, exhibition design, and domestic spaces, emphasizing open access for all. Her ambition for every project was fierce yet inclusive: plant life, circuses, boxing rings, and streets made their way into her creations. Her touch evaded easy classification—she could be monumental or refined—and though she often sought to simplify things, in the end the solutions were almost always complex. By comparison, Oscar Niemeyer, who designed Brasília (the city would become Brazil’s new capital in 1960), was a brand: you knew what you were going to get.

For a time, Bo Bardi was all but forgotten except by insiders. A celebration of her centenary in 2014 began a slow return to recognition. As this latest group of exhibitions prove, she has now been anointed the ultimate architectural heroine.

Material Girl

Born Achillina Bo in Rome in 1914, Bo Bardi would one day claim that she’d wanted to write her memoirs at the age of 25 but did not have enough material. Still, the headstrong young woman already possessed a keen artistic sensibility that was to mark her productive, tumultuous life. A self-described misfit who defied her mother, Bo Bardi adored her father, a builder whose first love was painting. Though her training in classical architecture gave her a solid grounding in history, she escaped her conservative upbringing and education by fleeing to Milan, where her expressive, colorful drawings easily found their way into freelance illustration and writing assignments for the magazines Domus and Lo Stile, both founded by the revered Italian designer Gio Ponti.

Bo Bardi thrived on the attention of male mentors, who were often infatuated with the seductive, opinionated young woman whose imagination and dynamism foreshadowed an unconventional talent. But bereft of any meaningful architecture career, she grew increasingly disturbed as many notables, including Ponti, allied with the Fascist Party that was gaining traction among Italians in the years leading up to the Second World War. An assignment to document living conditions in Italy following the end of the war left Bo Bardi with ideas about the need for humanitarian action and a feeling of solidarity with the disenfranchised. Her romance with Pietro Maria Bardi, a shrewd, older journalist, curator, and dealer looking for respite from postwar economic retrenchment—and, apparently, his wife—was to be dispositive. He had his marriage annulled; they quickly married to appease her family and departed for Brazil, where he had important contacts and she hoped to energize a meaningful career.

Bo Bardi’s touch evaded easy classification: she could be monumental or refined.

When the newlyweds arrived in Rio in 1946, the freedom and hopefulness in the air was a stark contrast to the gloom of postwar Milan. Bo Bardi, now 31, found it exhilarating. “I felt I was in some unimaginable country,” she said, “where everything was possible. ” Nevertheless, she was largely ignored by the entrenched Carioca School of modernist architecture—the war may have been over but her battle for recognition had just begun. When Bardi found a crucial supporter in Assis Chateaubriand, a newspaper magnate with aspirations to build a new museum, the couple decamped to São Paulo, a culturally underdeveloped city where they could more easily make their mark.

The trio quickly opened temporary museum spaces where Bo Bardi experimented with display and Bardi with unorthodox teaching methods and exhibitions focusing on new audiences such as children and native Brazilians. The Bardis sensed that their worth and the worth of the Brazilian people would develop in tandem, and they envisioned a day when the museum could be much more than a receptacle for art.

Read All About It

As the Bardis plotted a more capacious home for the new museum, they knew that popular media could help them gain traction with their daring, multi-disciplinary efforts. In their launch of the magazine Habitat, Bo Bardi found her voice as an advocate for indigenous culture and a vision that turned away from the paternalistic, European canon. The magazine achieved a global following. With fashion and Surrealism populating its pages alongside Marxist tracts and articles on basket weaving, it was a stealth project to wake up the bourgeoisie, alerting it to the wealth of creativity within Brazil’s own borders. Everything in the Bardis’ tool kit had an integrated socio-political function. They fast became a Paulista power couple.

If a woman’s home is her castle, the Casa de Vidro—the house Bo Bardi designed for them outside São Paulo, now the site of the Instituto Lina Bo e P. M. Bardi—was instead her laboratory, an environment “that offered protection…but at the same time remained open to everything.” With inspiration from Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright, Bo Bardi combined the transparency of glass with thin supporting pilotis to create a tree house with its rear hugging the hill, an inventive mashup of modern and colonial. Now almost entirely surrounded by her plantings—which she may have considered the real occupants of the property—the building feels at once open and private, a perfect setting for an ongoing salon that mixed the creative class with powerful figures in society and government. Being on display was a hallmark of Bo Bardi’s person and her projects. “I was born for this,” she would soon say.

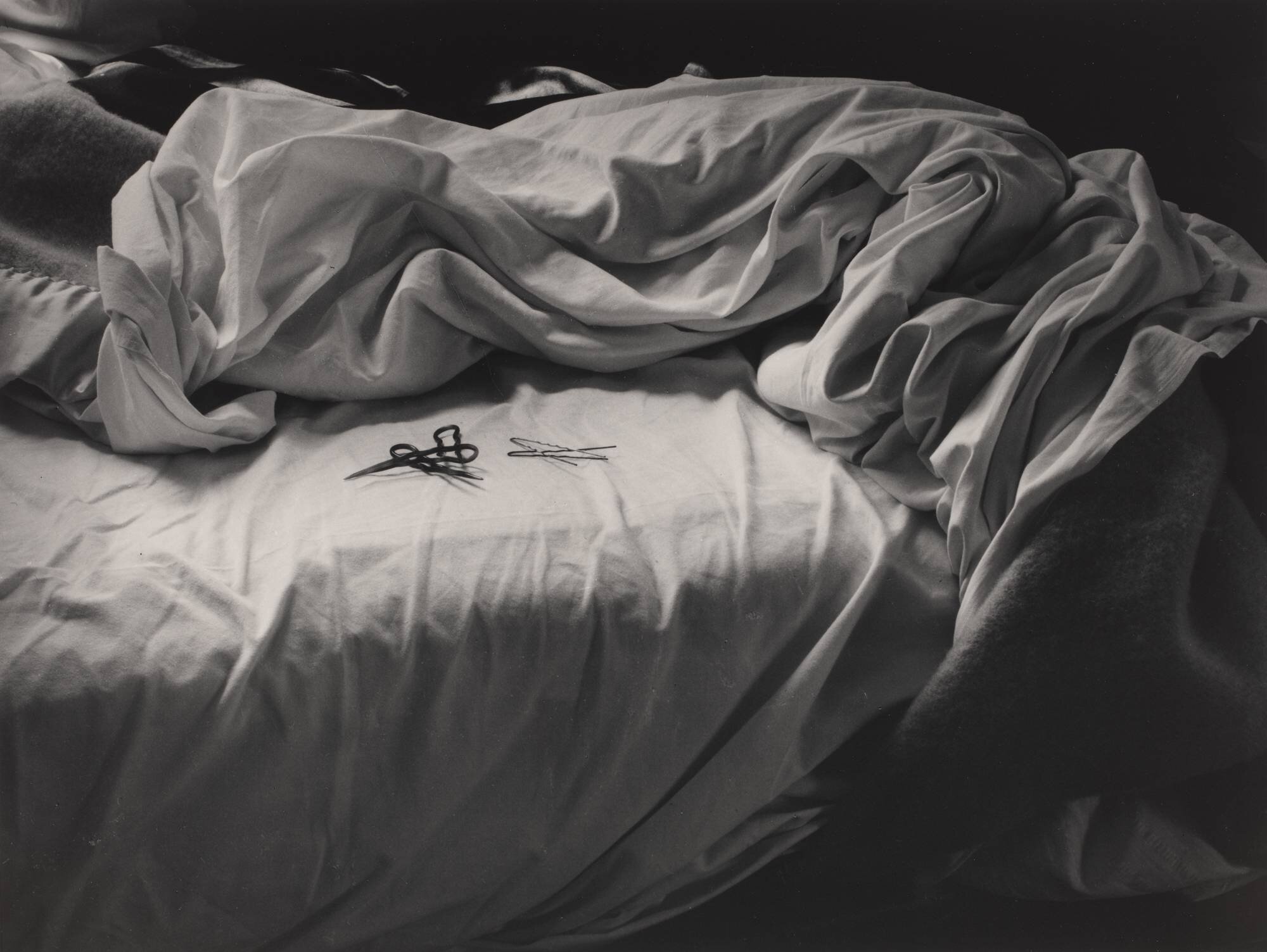

Despite her improved status, Bo Bardi longed for a refuge from the slow progress of the museum and other projects and, not incidentally, from the orbit of her powerful, unfaithful husband. Though Bo Bardi seemed fearless in transcending gender boundaries, her inner life was often a torment of self-doubt.

Alternately adored by and alienated from her collaborators, Bo Bardi struggled to receive commissions.

Salvador de Bahía, the former colonial capital, would become the conduit for Bo Bardi’s transformation from stylish belle of the ball to the substantive, makeup-free, “Anna Magnani of architecture,” as the critic Martin Filler has called her. The ethnically diverse city buttressed Bo Bardi’s growing belief that architects were not handmaidens of the aristocracy but of the people. In Salvador, like the drumming and dance ensembles known as sambistas, Bo Bardi became a whirlwind of movement. She taught at the university; wrote a Sunday column; co-founded and directed the Museum of Modern Art of Bahía in a sugar mill she adapted; curated a landmark exhibition on the indigenous culture of Brazil’s northeast region, Nordeste; ran educational programs; and embarked on long-term collaborations with the filmmaker Glauber Rocha, the ethnologist and photographer Pierre Verger, and the theater director Martim Goncalves.

In a second wave, Bo Bardi master-planned a renewal of the colorful city center that included the Casa do Benin for African heritage and the Ladeira Da Misericordia—a narrow, crumbling street that hugged the edge of the city—which she revitalized by integrating her colleague João Lima’s thin, undulating, concrete buttresses into a housing and restaurant complex. Chairs she designed evolved from sleek leather buckets to roadside perches made of twigs: beauty had become a barometer of decadence. “No one can save themselves by design,” she wrote. “Can a beautiful glass save us from thirst? Can a very beautiful dish … save us from hunger, misery, illness and unemployment?”

Though Bo Bardi’s productive years in and out of Bahía ended in humiliation and intimidation—her volatility made enemies of key supporters and the military junta—they freed her to tap into the region’s rich Portuguese and African traditions along with leftist politics and the avant-garde. She came into her own. Bo Bardi’s baggy pants, blue workers shirts, and free-flowing hair announced Salvador’s parallel personal impact. Where she had once needed to be desired as a woman, now she could lay claim to being noticed as a propulsive thinker and doer.

Spot the Difference

By the time Queen Elizabeth arrived in São Paulo to inaugurate the opening of the MASP, gone was the Bo Bardi of elaborate ensembles. In her place: the public intellectual and architect who excelled at ruffling feathers. “I want to clarify that…it was my intention to destroy the aura that always surrounds a museum,” she wrote. The museum instead became a social and cultural resource for the metropolis, a new town square.