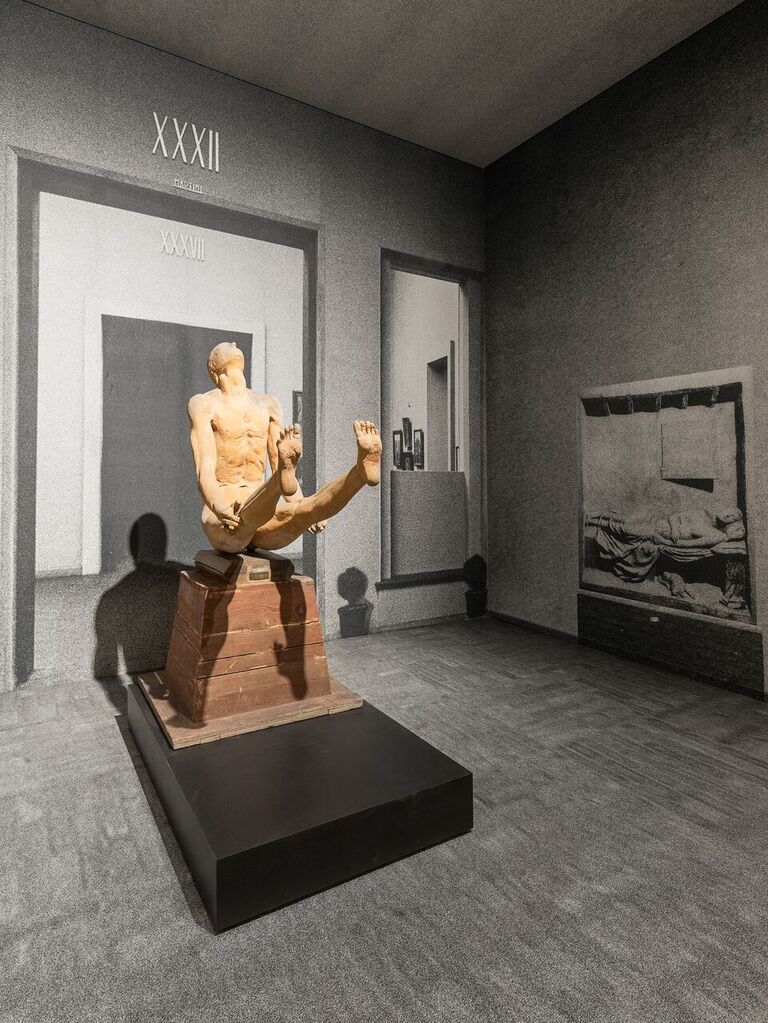

Normally, Antonio Canova’s sculpture of Pauline Bonaparte as Venus is flanked by some diminutive Roman sculptures behind her. Not now. For some inexplicable reason- or the latest misbegotten attempt to bring in a wider population—the Galleria Borghese in Rome has invited Damien Hirst to put his work throughout the galleries in a counterpoint. Who ever thought that the ever and already fabulous Galleria Borghese needed updating? Hirst is the Emperor’s Old Clothes, and here instead we have some real Emperors of art and history. What?!!! There is already hardly a ticket booking to be had at the Galleria and Covid isn’t even over. Sometimes the interspersion of modern arts into antiquity can work ( the nearby Galleria Nazionale d’arte Moderna does a splendid job of a likeminded juxtaposition). Save us from this plague of impoverished confidence in your collections museum curators and directors.

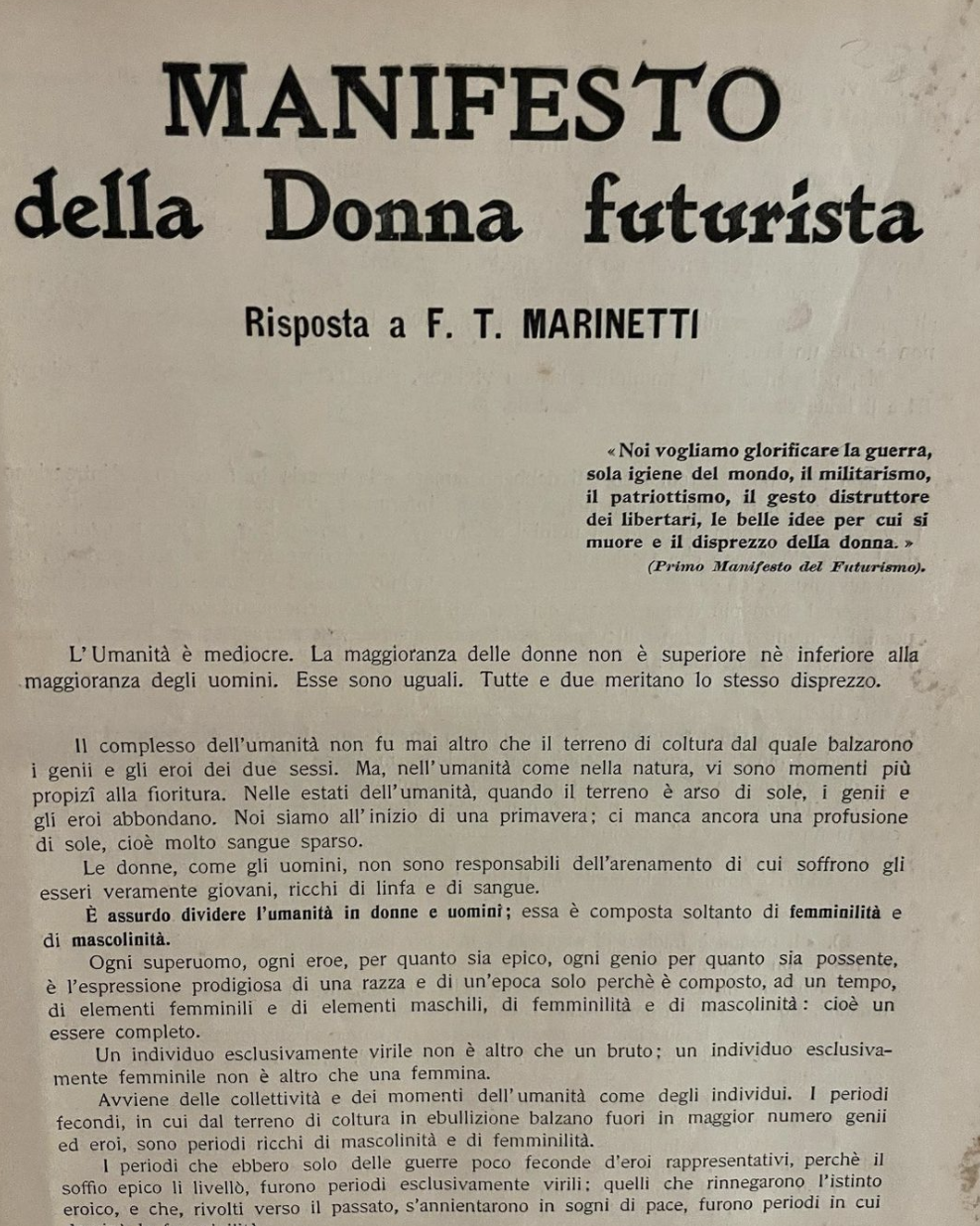

The Italian First Feminists

Though they are not as well known, the Italian first wave feminists were busy fighting the repression of Mussolini and the restrictive, male society of pre war Italy. As usual ahead of the pack were the artists. This rousing declaration by Marinetti who had penned so many of the Futurist tracts only one of many efforts. If you were going to be as fast as a train or a car you better have a woman be out front. Benedetta Cappa an artist and his wife who resented the misogyny of even the fellow futurists said, “I am too free and rebellious…I do not want to be restricted. I only want to be me”.

Giacomelli's Postwar Italy

The Mario Giacomelli retrospective at the Getty is striking, first for introducing me to this talented photographer, but also because of the diversity of his work.

My eye drifted to his high contrast prints which felt akin to Saul Bass movie posters. This image from around 1957 from his portfolio of the Italian people, La Gente is a particularly good example of the deep blacks set against brilliant whites.

Giacomelli toured Italy to capture the postwar images which we now think of as iconic from the films of the period--the craggy local faces, the children gathering in the town square, the unemployed men. Here an old townswoman approaches.

Lina's World; my story for Air Mail News

“I felt I was in some unimaginable country where everything was possible,” said Italian-born Bo Bardi when she arrived in Brazil.

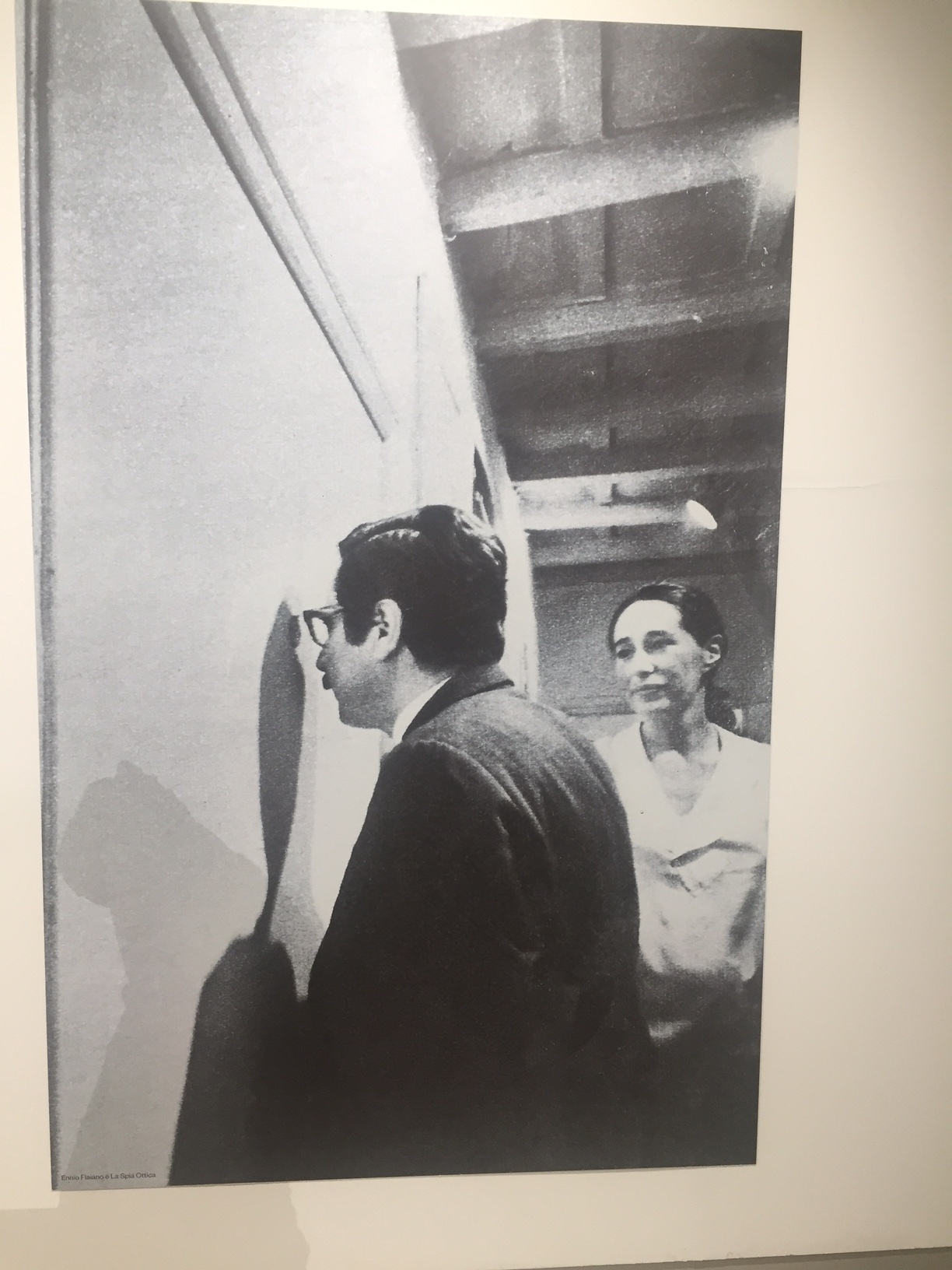

In a career filled with cliffhangers and high drama, there was likely no moment more urgent for the polymath architect Lina Bo Bardi than the one captured by a photographer in 1967 (above). In her on-site design office under the grand span of the Museum of Art of São Paulo (MASP), her riskiest architectural scheme to date, the restive, Italian-born Bo Bardi, was, for a rare moment, stationary. The project in her adopted homeland had been riven with years of frustrating political setbacks and engineering fixes to her radical design, and now she was racing to meet the 1968 inauguration by Queen Elizabeth. Beside Bo Bardi, Van Gogh’s The Student (The Postman’s Son, Gamin au Képi) was encased in a prototype of her innovative freestanding glass-easel display system, which allowed viewers to circle paintings as if meeting a friend. Behind her stood construction workers, a symbol of the premium she placed on architects acting as instruments of and for the “people”—to whose creativity and needs she was devoted—and not gods who put their designs and egos first.

Recently the subject of “Habitat,” a three-venue career retrospective, and a show of drawings at the Carnegie Museum, all cut short by the coronavirus, Bo Bardi’s work is included in newly reopened exhibitions at the Design Museum Gent, in Belgium, and the Vitra Museum, in Germany. Bo Bardi, who died in 1992, has arrived at the pinnacle of international recognition as much for her diverse body of work as for the original way she went about it.

High-strung, alternately adored by and alienated from her collaborators, Bo Bardi craved attention but struggled for years before receiving any significant commissions. In the interim, she poured her considerable energies into editorial and educational projects, exhibition design, and domestic spaces, emphasizing open access for all. Her ambition for every project was fierce yet inclusive: plant life, circuses, boxing rings, and streets made their way into her creations. Her touch evaded easy classification—she could be monumental or refined—and though she often sought to simplify things, in the end the solutions were almost always complex. By comparison, Oscar Niemeyer, who designed Brasília (the city would become Brazil’s new capital in 1960), was a brand: you knew what you were going to get.

For a time, Bo Bardi was all but forgotten except by insiders. A celebration of her centenary in 2014 began a slow return to recognition. As this latest group of exhibitions prove, she has now been anointed the ultimate architectural heroine.

Material Girl

Born Achillina Bo in Rome in 1914, Bo Bardi would one day claim that she’d wanted to write her memoirs at the age of 25 but did not have enough material. Still, the headstrong young woman already possessed a keen artistic sensibility that was to mark her productive, tumultuous life. A self-described misfit who defied her mother, Bo Bardi adored her father, a builder whose first love was painting. Though her training in classical architecture gave her a solid grounding in history, she escaped her conservative upbringing and education by fleeing to Milan, where her expressive, colorful drawings easily found their way into freelance illustration and writing assignments for the magazines Domus and Lo Stile, both founded by the revered Italian designer Gio Ponti.

Bo Bardi thrived on the attention of male mentors, who were often infatuated with the seductive, opinionated young woman whose imagination and dynamism foreshadowed an unconventional talent. But bereft of any meaningful architecture career, she grew increasingly disturbed as many notables, including Ponti, allied with the Fascist Party that was gaining traction among Italians in the years leading up to the Second World War. An assignment to document living conditions in Italy following the end of the war left Bo Bardi with ideas about the need for humanitarian action and a feeling of solidarity with the disenfranchised. Her romance with Pietro Maria Bardi, a shrewd, older journalist, curator, and dealer looking for respite from postwar economic retrenchment—and, apparently, his wife—was to be dispositive. He had his marriage annulled; they quickly married to appease her family and departed for Brazil, where he had important contacts and she hoped to energize a meaningful career.

Bo Bardi’s touch evaded easy classification: she could be monumental or refined.

When the newlyweds arrived in Rio in 1946, the freedom and hopefulness in the air was a stark contrast to the gloom of postwar Milan. Bo Bardi, now 31, found it exhilarating. “I felt I was in some unimaginable country,” she said, “where everything was possible. ” Nevertheless, she was largely ignored by the entrenched Carioca School of modernist architecture—the war may have been over but her battle for recognition had just begun. When Bardi found a crucial supporter in Assis Chateaubriand, a newspaper magnate with aspirations to build a new museum, the couple decamped to São Paulo, a culturally underdeveloped city where they could more easily make their mark.

The trio quickly opened temporary museum spaces where Bo Bardi experimented with display and Bardi with unorthodox teaching methods and exhibitions focusing on new audiences such as children and native Brazilians. The Bardis sensed that their worth and the worth of the Brazilian people would develop in tandem, and they envisioned a day when the museum could be much more than a receptacle for art.

Read All About It

As the Bardis plotted a more capacious home for the new museum, they knew that popular media could help them gain traction with their daring, multi-disciplinary efforts. In their launch of the magazine Habitat, Bo Bardi found her voice as an advocate for indigenous culture and a vision that turned away from the paternalistic, European canon. The magazine achieved a global following. With fashion and Surrealism populating its pages alongside Marxist tracts and articles on basket weaving, it was a stealth project to wake up the bourgeoisie, alerting it to the wealth of creativity within Brazil’s own borders. Everything in the Bardis’ tool kit had an integrated socio-political function. They fast became a Paulista power couple.

If a woman’s home is her castle, the Casa de Vidro—the house Bo Bardi designed for them outside São Paulo, now the site of the Instituto Lina Bo e P. M. Bardi—was instead her laboratory, an environment “that offered protection…but at the same time remained open to everything.” With inspiration from Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright, Bo Bardi combined the transparency of glass with thin supporting pilotis to create a tree house with its rear hugging the hill, an inventive mashup of modern and colonial. Now almost entirely surrounded by her plantings—which she may have considered the real occupants of the property—the building feels at once open and private, a perfect setting for an ongoing salon that mixed the creative class with powerful figures in society and government. Being on display was a hallmark of Bo Bardi’s person and her projects. “I was born for this,” she would soon say.

Despite her improved status, Bo Bardi longed for a refuge from the slow progress of the museum and other projects and, not incidentally, from the orbit of her powerful, unfaithful husband. Though Bo Bardi seemed fearless in transcending gender boundaries, her inner life was often a torment of self-doubt.

Alternately adored by and alienated from her collaborators, Bo Bardi struggled to receive commissions.

Salvador de Bahía, the former colonial capital, would become the conduit for Bo Bardi’s transformation from stylish belle of the ball to the substantive, makeup-free, “Anna Magnani of architecture,” as the critic Martin Filler has called her. The ethnically diverse city buttressed Bo Bardi’s growing belief that architects were not handmaidens of the aristocracy but of the people. In Salvador, like the drumming and dance ensembles known as sambistas, Bo Bardi became a whirlwind of movement. She taught at the university; wrote a Sunday column; co-founded and directed the Museum of Modern Art of Bahía in a sugar mill she adapted; curated a landmark exhibition on the indigenous culture of Brazil’s northeast region, Nordeste; ran educational programs; and embarked on long-term collaborations with the filmmaker Glauber Rocha, the ethnologist and photographer Pierre Verger, and the theater director Martim Goncalves.

In a second wave, Bo Bardi master-planned a renewal of the colorful city center that included the Casa do Benin for African heritage and the Ladeira Da Misericordia—a narrow, crumbling street that hugged the edge of the city—which she revitalized by integrating her colleague João Lima’s thin, undulating, concrete buttresses into a housing and restaurant complex. Chairs she designed evolved from sleek leather buckets to roadside perches made of twigs: beauty had become a barometer of decadence. “No one can save themselves by design,” she wrote. “Can a beautiful glass save us from thirst? Can a very beautiful dish … save us from hunger, misery, illness and unemployment?”

Though Bo Bardi’s productive years in and out of Bahía ended in humiliation and intimidation—her volatility made enemies of key supporters and the military junta—they freed her to tap into the region’s rich Portuguese and African traditions along with leftist politics and the avant-garde. She came into her own. Bo Bardi’s baggy pants, blue workers shirts, and free-flowing hair announced Salvador’s parallel personal impact. Where she had once needed to be desired as a woman, now she could lay claim to being noticed as a propulsive thinker and doer.

Spot the Difference

By the time Queen Elizabeth arrived in São Paulo to inaugurate the opening of the MASP, gone was the Bo Bardi of elaborate ensembles. In her place: the public intellectual and architect who excelled at ruffling feathers. “I want to clarify that…it was my intention to destroy the aura that always surrounds a museum,” she wrote. The museum instead became a social and cultural resource for the metropolis, a new town square.

Bardi’s freestanding glass easels display art inside MASP.

Bo Bardi’s last decades cemented her reputation as an exceptional innovator. Her most consequential commission was the transformation of an old barrel factory in a working class section of São Paulo into the SESC Leisure Center on the Rua Pompéia. The inviting spaces born of low-rise, cavernous sheds became a library, a cafeteria, art studios, a theater, and a public “living room” with a winding reflecting pool. The Center culminated in delicate, ramped concrete structures for sports, all free and open to the public. Bo Bardi designed the furnishings, signage, even new uniforms: this was a project she proudly owned in its entirety. Once again, her insistence on an on-site office made the posse of young male architects and construction workers more nimble; she may have been demanding, but she inspired ardent dedication.

She had once needed to be desired as a woman; now Bo Bardi could lay claim to being a propulsive thinker and doer.

Bo Bardi died at age 77 after declining health, her legacy not assured. She was that rare combination of populist and autocrat and many of her interventions were allowed to deteriorate, or worse, were suppressed. Though the Getty Conservation Institute made a survey grant for the Casa de Vidro, and the World Monuments Fund put the Ladeira on their Watch List, a visitor last year found only debris and weeds in the largely inaccessible abandoned hilltop bar which had incorporated nature and her signature cloud windows. In Salvador’s Gregório de Matos Theater, dozens of her folding wooden chairs were stored in a grimy heap next to garbage and paint cans. Her elegant Casa do Benin has had to survive as a gift shop. Bo Bardi was able to supervise repairs to São Paulo’s MASP before her death but not to prevent 20 years of posthumous decline, as well as the removal of her unique painting display system.

Happily, the glass easels are now returned to open formation and the museum is again on surer footing. But increasingly diminished resources for culture in Brazil are worrying. What would Bo Bardi think—however holistic their intentions—of the Danish starchitect Bjarke Ingels, who recently toured Bo Bardi’s beloved Nordeste with members of a real estate conglomerate and then met with authoritarian President Jair Bolsonaro to receive his blessing for large-scale tourism development?

Both Bo Bardi’s published writings and her buildings are vigorous counter-narratives for a bottom-up, inclusive world. Her love for the circus—she once made space for it under the massive span of MASP, and used it for her plan of the Espírito Santo do Cerrado Church in Uberlândia, Brazil—is emblematic: all are welcome under Bo Bardi’s Big Top.

Photos: Lew Parrella © Colección Instituto Bardi/ Casa de Vidro São Paulo; Courtesy of Museo Jumex.

Pietro Consagra's spectacular theater in Gibellina Sicily at risk

This week would have been the opening of the Architecture Biennale in Venice, now postponed until this time 2021. In 2018, a project about the extraordinary 1972 theater of Pietro Consagra was center stage in the Italian pavilion. When I got to Gibellina and saw it, even with the debris in front and the disrepair, it was still one of the most beautiful structures, an example of this visionary sculptor's who envisaged each inhabitant would be transformed – in a “The Frontal City”, so they could "experience art...to keep oneself suspicious, susceptible, nervous, intolerant, evasive, enthusiastic, balanced, unbalanced, attentive, aggressive, lazy, imaginative, libidinous, free, ungraspable.” Consagra continued, “We no longer wish to live in cubes, nor in spheres or tubes. We do not want to end up in conventional dimensions dictated by the standards of mass production. We do not want to live within any concept of normalization...Whatever space we happen to use must be mobile, temporary, transparent, paradoxical and amenable to fluctuating ideas. It must evade the eternal structures of Power”. Today an effort is still ongoing to bring this utopian structure back to life.

Nanda Vigo and her Anthropomorphic Traces in Gibellina Sicily

When I was in Gibellina (see my report on Artnet) Sicily discovering the history of the modernist town that had been built adjacent to the ruins famously covered in concrete by Alberto Burri, I corresponded with designer and artist Nanda Vigo, who has died. Vigo who had worked with Gio Ponti and lived with Piero Manzoni, designed the 'Anthropomorphic Tracks" repurposed out of elements that had been destroyed in the 1968 earthquake. Vigo said (in her own translation), "My idea was to give remembers of the old village, so I recovered the remains of the very old fountain, still there from the time when the village was founded from Arabian people, and I rebuild it in the new town. I did the same with a beautiful “normanno” arch and with many pillars from the main church. All together I called “tracce antropomorfe” (anthropomorphic tracks). Vigo was a leader in the effort to help the town's mayor Ludovico Carrao in marshaling artists to help build this new city. Very candidly she considered the project something of a failure, " today Gibellina looks like a dead town, without the look and the hand of Corrao. The municipality of the town don’t take care at the monuments, enough the Burri “cretto” is now save thank to the private policy. There are living only old people, young population leave for the main town or strange country." Gibellina is being rebuilt, and Sicily is one of the first Italian areas to reopen. Still, I fear for the important but delicate ongoing preservation project.

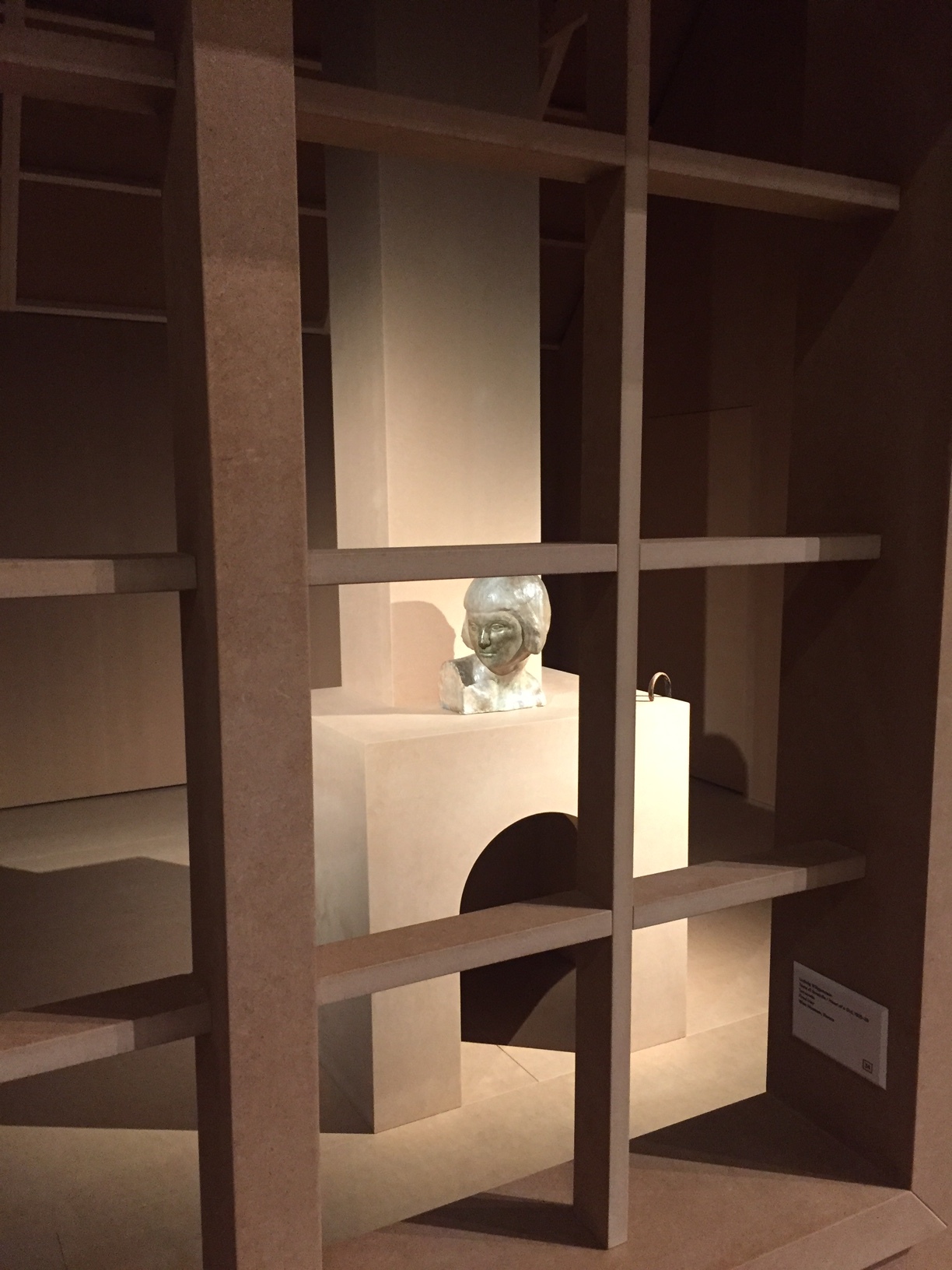

Magazzino Italian Art Museum is a captivating outpost of passionate collecting

Private museums are all the rage. A month ago, Glenstone opened in Maryland. There’s the Broad and so many others worldwide.

But Magazzino Italian Art Museum seems an outlier. It took me a year to finally have a Sunday to get up to Cold Spring. I had hoped for a better show of leaves along the Hudson River train route, but like everywhere else, global warming has pushed back on nature. For at least the second year in a row, there were only muddy browns and golds with the occasional red pop to remind us of what we were missing.

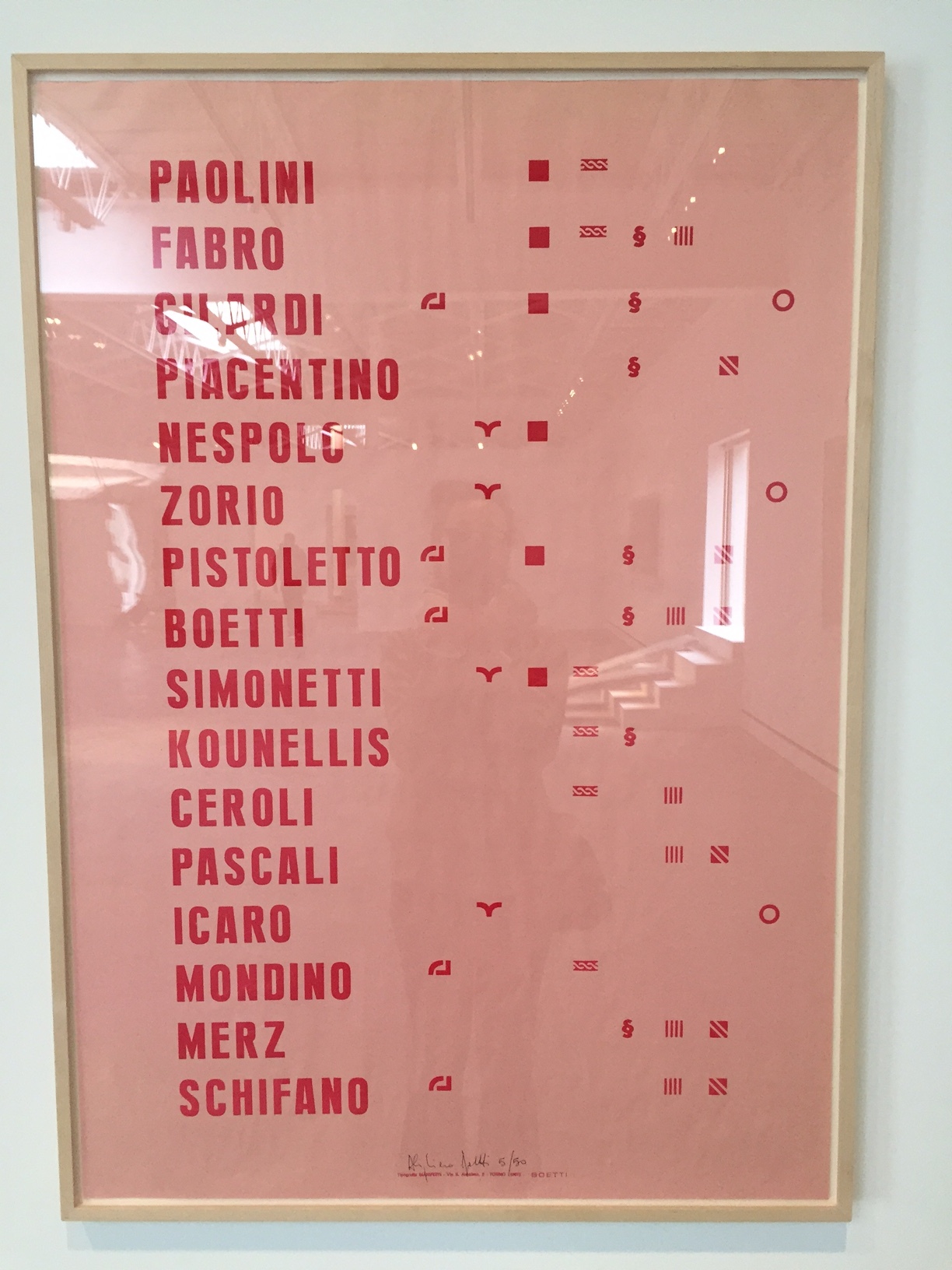

Derived from the collection of Nancy Olnick and Giorgio Spanu, the largely Arte Povera works at Magazzino were lovingly collected with intense focus and scholarship. Arte Povera really becomes understandable at this museum, its motives less murky. Having been lured by post war Torino and north Italy and then tumbling headlong into Sicily and Puglia these last years, the art had special resonance for me.

Margherita Stein was Arte Povera’s champion in Italy and she has passed the torch to the Olnick/Spanus with white heat. Architect Miguel Quismondo has designed a home for them in nearby Garrison and they asked him to carry on with the museum. Having only seen exterior shots of Glenstone’s gray pavilions and coming upon the (smaller) Magazzino gray pavilions, I was slightly put off by the austerity. Once inside however, there is a warmth and logical spaciousness that felt in keeping with the art.

An hour and a half long series of short films hosted by Germano Celant who coined the term Arte Povera at the entry is too long for one go, but 15 minutes will give you the necessary tools to approach the art. No wall labels of course (my pet peeve) but the small booklet you are given at the entrance is a pithy port to the artists and their works.

Celant explains the crucial animating theory of this group, largely a sixties reaction to industrialization and the loss of nature and natural elements. Taking their cues from water, air, land and fire, the primitive elements revered by the Greeks, as well as the animal kingdom, this self-organized Italian group juxtaposed the work of man and the work of nature in novel ways. The point, a very contemporary one, is that we are losing our way.

Alas, until Marisa Merz’s work was ‘exhumed’ a few years ago at the Whitney there was little attention paid to the concurrent work of women. Merz--husband Mario was more closely associated with the group—is here represented by works that captivate for their “warmer” delivery system.

Workers and students were unusually aligned, especially in Europe during the late sixties and the art reflects a rejection of the status quo, then more oriented towards Pop and Minimalism. Other groups of Italian artists were seeking a different way out of the postwar but the Poveristos (my coinage) including Michelangelo Pistoletto, Marco Anelli, Alighiero Boetti, Luciano Fabro, Pino Pascali, Jannis Kounellis, Giuseppe Penone, Giulio Paolini marched to their own drum.

The Olnick Spanus also support contemporary Italian art, some currently on view at the Italian Culture Institute and the exhibition, which closes this week, makes a good pairing with the works at the museum.

Palermo Parte Due

In addition to the Manifesta sites a few things worth noting. Besides scores of beautiful Baroque churches and oratorios which you can find in any guidebook:

1. Palazzo Abatellis which houses the excellent Carlo Scarpa intervention into the Galleria Regionale della Sicilia. Like his museum in Verona, the Castelvecchio, Scarpa takes the essence of ancient things and makes them new again. Too bad he is not alive today to make museum architects understand that they do not have to show off.

2. The Marionette Museum is splendid. The most complete number of examples I have ever seen from around the world. I did not have a chance to attend a show but I feel sure they are expert.

3. The Palermo Markets. I thought Santa Monica and the Embarcadero were good. But the Capo and the Ballero markets in Palermo put them in their place. I did not have a kitchen, but if you stay at the new Planeta Palermo just opened, you can have a kitchen. Otherwise, I suggest staying in the center at the BB22, extremely well located with very nice staff.

4. Dinner at Bisso Bistrot. Very reasonable, good, fun, centrally located. No reservations.

5. The Teatro Massimo. The third largest opera house after Paris and Vienna. After the Sahel opera it was hard to adjust to a Fernand Botero inspired circus themed Elisir d’Amore—which I also had seen recently in Vienna in a much frothier, saccharine production. Nevertheless no matter how you present it, this story of a faux magic potion which unites the lovers in the end really is showing its vintage. In the Teatro, there is little or no a/c so the ladies bring fans. I loved this, and the little red lights in each box (no actual raked seating, and a flat orchestra). After the little theaters of Orvieto and Spoleto, (I have only seen Fenice and Scala spaces not any operas) I am more convinced than ever that the future of opera, so endangered at home is in the smalls. When you exit onto the red carpeted stairs, there is no way not to recall The Godfather and for that alone it is worth the price of admission.

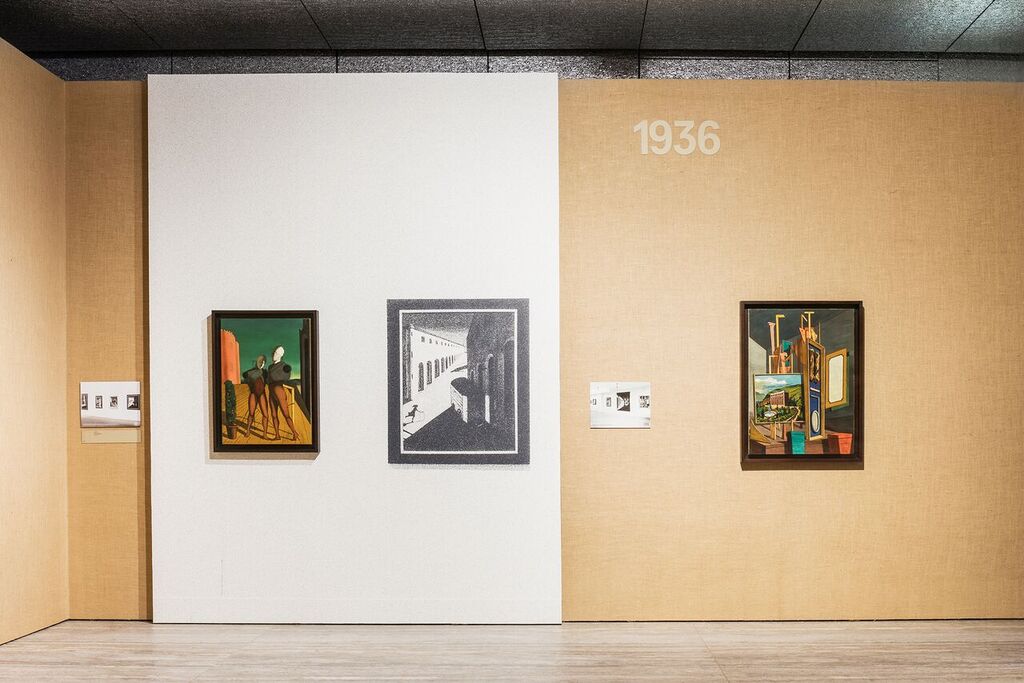

Post Zang Tumb Tuuum. Art Life Politics: Italia 1918–1943

The Prada Foundation in Venice, always a sumptuous experience has now become even more spectacular with the latest addition of Rem Koolhaas’s Torre, a multi story tower with installations that culminates in a restaurant modeled after the Four Seasons. It was closed when I was there so I cannot report on that, only that the spicy tuna sandwich at the original cafe was delicious and fast.

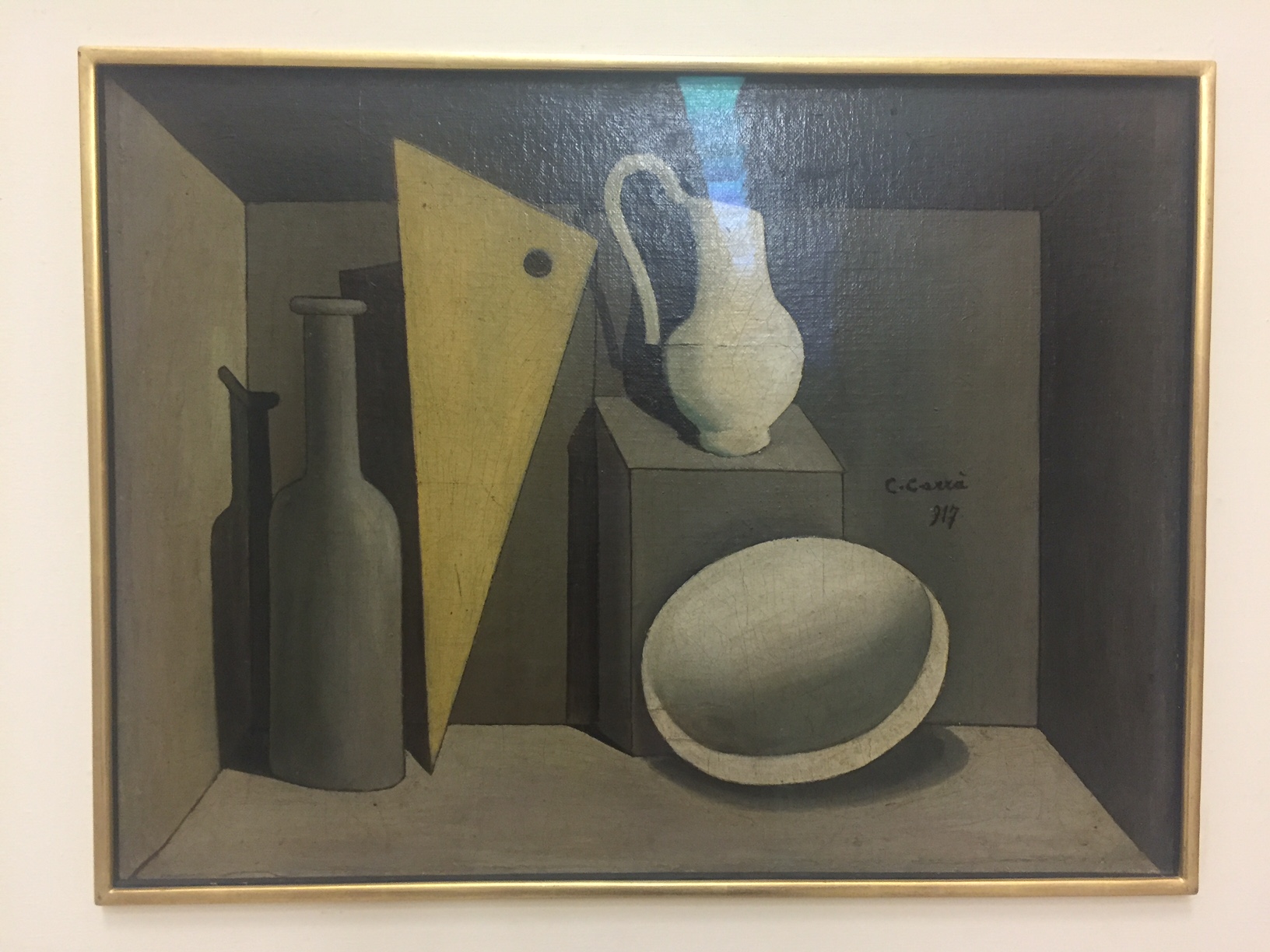

You need to be fast because there is much to see, especially now Post Zang Tumb Tuuum, a show that would not have been possible just a few years ago on the art of Italy pre and post WW2. It begins with the great Futurists (I can never have enough Boccocconi or Severni, though there are not the best examples here) and carries on through the Fascistic era. Now, buildings and paintings we once thought were edifici non grata are being newly rediscovered as examples of a certain style. Much of this art would have passed as Flea Market Art about a decade ago and it is still not the strongest period, but the curators have added vintage books, posters and ephemera and so we have an understanding of the motivations.

I am a bit of a sucker for this stuff, even in its middlebrow incarnations, because in the aggregate there is an elegance that defies the often repressive or anti Semitic period during which it was made. Artists such as de Chirico had already been fingered, but there are many society painters and designers who must have been working with one eye closed.

It’s a very large show which takes up many pavilions and I recommend it both as an artifact and a welcome addition to scholarship of the period which many of us having been avoiding.

A local very knowledgeable friend who accompanied me on my visit said, “Who knows how long this all can last? “ By that she meant that retail luxury business is down worldwide and that Prada too had been affected. Though many luxury houses have contributed mightily to the arts, I would have to say that the scholarship at Prada is always top drawer and introduces me to work with an excellent historical perspective.

Prada Foundation in Venice

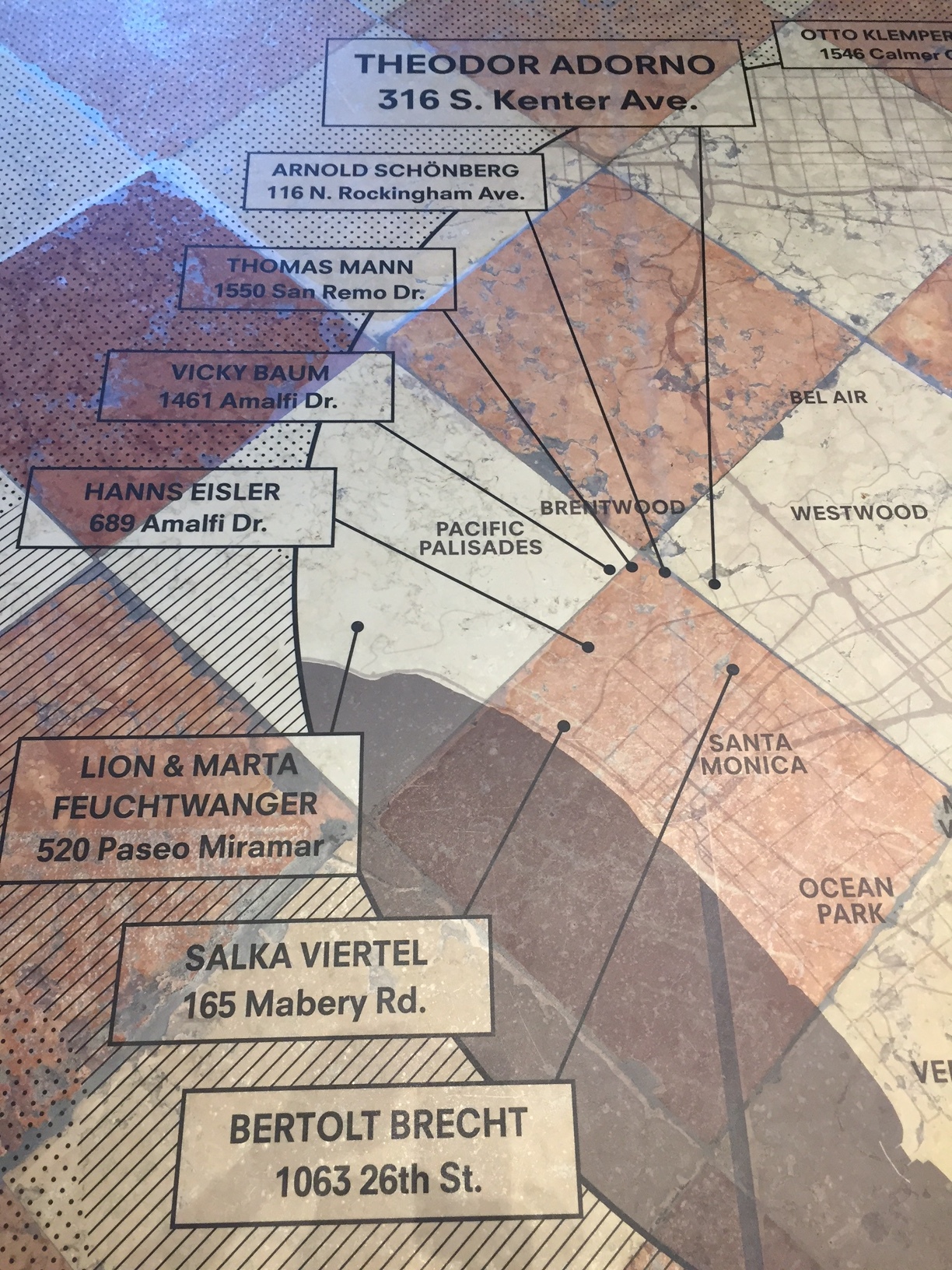

At the Prada Foundation in Venice, an exhibition Machines À Penser has a title which is precisely the opposite of what one expects.

Inside the always impeccably curated space is a show about philosophers and their hideaway huts. It is a testament to the value of escaping to do one's work, to the perennial Virginia Woolf wish for a Room of One's Own or as Dieter Roelstraete, the curator put it, "the enduring infatuation with fantasies of flight and the architecture of retreat"

Heidegger, Wittgenstein and Adorno the focus of the show had 'huts' that are still vaguely extant.

Do not think of Easthampton or Santa Barbara. Instead think of remote Norway or Germany or even the Pacific Palisades as the biggest surprise for me was a huge blow up of the Villa Aurora at the entry which is right near me in Los Angeles and which was the getaway of Lionel Feuchtwanger and the nearby 'hut's of Salka Viertel, Hans Eisner, Thomas Mann (now saved by the German government), Arnold Schoenberg, Brecht, Alma Mahler

The Palisades can be a good if isolating place with precious little spontaneity but that's probably what the philosophers were seeking. Refuge. Thinking about the relationship of thought to environment is omnipresent in my life and often confused with happiness. No, the exhibition is not about contentment but rather the mental space to do one's work.

Again I was sorry that few women were included as surely women have longed to escape to think even perhaps more than men.

Rachel Cusk's new book, Kudos, which I've just begun, has a scathing section on an Italian contessa's writers retreat only thinly disguised as is most of her work. Here the writer's are hardly able to work and instead sit staring at the beautiful walls or tapestries in a kind of mad desperation. One packs up his bag and leaves on the second day, another wishes she could but her suitcases are too heavy.

The intellectuals in this exhibit are more bonded with their private retreats which depend on barebones cooking (women seem to be present for that part).

Contemporary artists were asked to contribute to this theme. (Again: very few women) Alexander Kluge's film Cold is the Chain of God was far and away the most charming, an animation which included Napoleon's armies suffering in the cold, lots of beautiful snow and great wit.

The Palazzo Cini

The Palazzo Cini is right next door to the Peggy Guggenheim but it is largely skipped by tourists and so they are giving discount passes at the Peggy.

The Cini family also founded the San Giorgio Island install. This is merely an earlier iteration of the Prada/Pinault concept. Cini was a rich industrialist collector who also had a religious bent. Two Palazzi were converted by his daughter for a pot pourri of paintings sculptures and porcelains.

There are some nice things (a della Francesca Madonna and child and a great Pontormo portrait of Two Friends) but the discovery for me is the superior circular staircase by Tomaso Buzzi which was added in the fifties. An Imaginary Architecture show of drawings is up to coincide with the Biennale.

Carlo Scarpa room at the Ca Foscari public university in Venice

After three tries, I finally was able to get into the famous Carlo Scarpa room at the Ca Foscari public university in Venice.

This university seems a wonderful environment with this once in a lifetime situated campus and I was told it has excellent faculty and courses which can be had for a quarter the price of American universities.

In addition, it holds a rare Scarpa room which he designed for lectures including the chairs, the dais with its removable tile floor,, the folding window screens and wood fretted ceiling. Having done the Scarpa route outside Venice on one of my last trips, this was the excellent dessert. There is a tour which is given and I recommend it as my way of getting upstairs was entirely too random and complicated.

Fondazione Carriero

Situated behind a red brick facade with barely a number outside is the Fondazione Carriero, yet another private foundation begun by a wealthy founder.

Tucked away inside a 14th-15th century private Milanese home, redone by Gae Aulenti (this much more successful than the Musee d'Orsay) originally for a bank, the quiet galleries are both hidden and free and open to the public.

Still, this one is so tasteful as to be modest and for two more weeks, an elegant Sol Le Witt show curated by Rem Koolhaas and Francesco Stocchi is on view. Le Witt is mostly represented at Dia and at Mass Moca in huge installations where he loses me. Here, I found a measure of contemplation that worked.

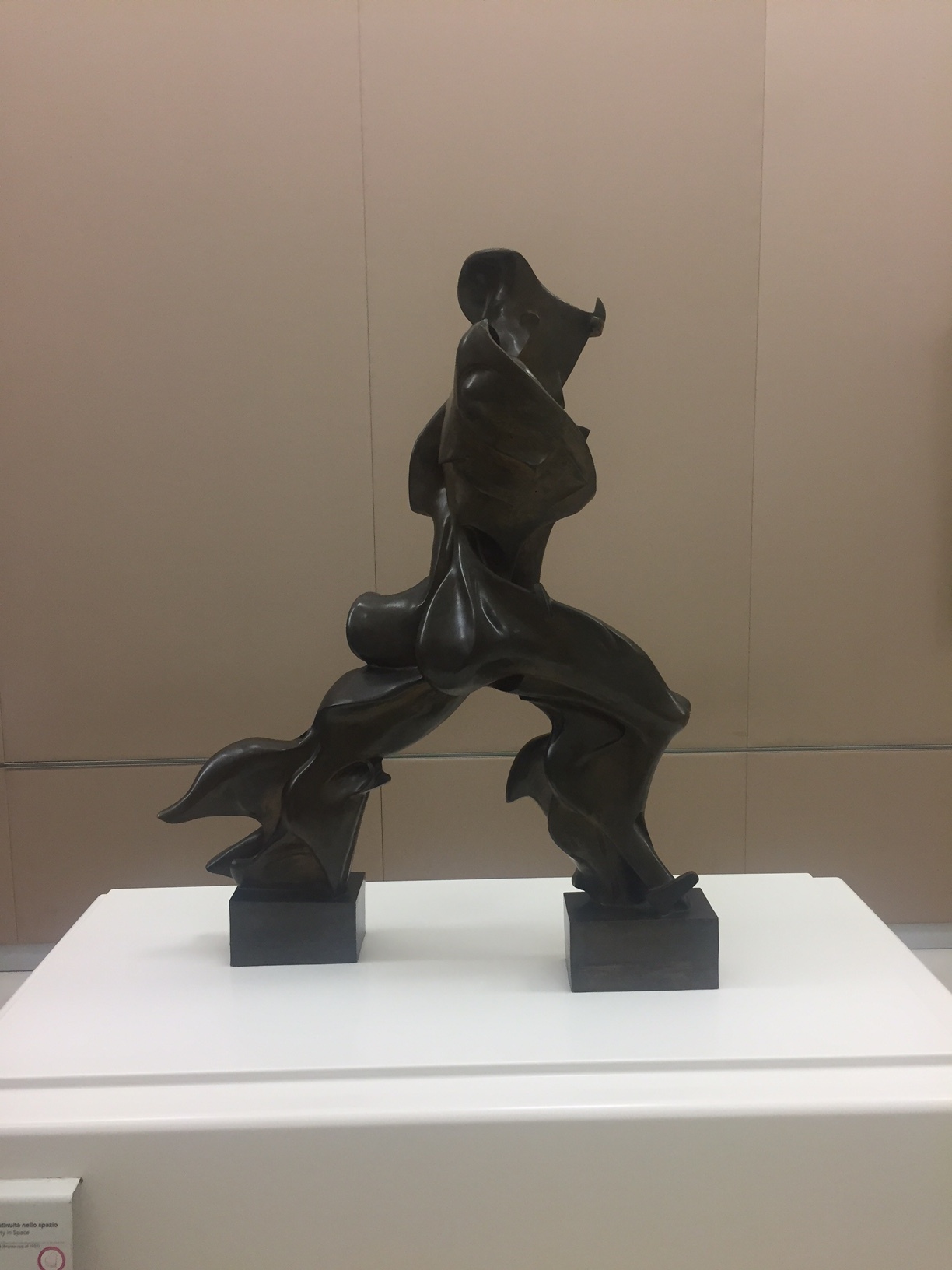

Museo Del Novecento

The Museo de Novecento is stuffed into a wonderfully fascistic building Palazzo dell'Arengario next to the Duomo, which I never recognize anymore, as it is white now instead of the black I remember. Tourists throng the square but Milan is still mostly free of American tourists (to their detriment. It is a wonderfully rich city).

Though poorly retrofitted, the collection inspires a certain admiration: it is filled with Italian futurists and local artists, unknown to us, but worthy of attention. And at the top, the view of the Piazza is splendid.