A Magazzino Museum lecture by Leslie Cozzi on the star couple of Arte Povera Marisa and Mario Merz which continued the series reminded me of the pow I got on seeing her retrospective at the Met Breuer, The Sky is a Great Space and again at the Hammer in 2017.

Here was a woman with a young child and a husband who was making art and willing to take over her own apartment with an installation of The Living Sculpture--Notice Me!—but was unwilling to engage with a public dialogue until decades later. This was complicated. In between the hours of feeding and caring, she made these incredible, large sculptures out of aluminum sheeting. They are thrilling. She also made little knit scarpette-booties-and other knitted sculptures that so reminded me of Ruth Asawa's work. Those women made lemonade....mothers everywhere take heart!

To round out the Magazzino lecture please take a look at a talk from that Met show from pre-Zoom days with the beloved, late, Germano Celant on the panel who knew the Merz family very well. It's so moving to hear him talk about this couple.

The Violin Stories in Art

Violin Stories: I first saw this lovely painting Girl with Violin from 1928. by Antonietta Raphael in Lucia Re's Magazzino Museum lecture on Italian art couples (see yesterday's post).

Raphael had been a serious student of music by way of London and Paris, but she returned to Rome to attend art school and met her lifelong partner Mario Mafai with whom she had three talented daughters. She was a sculptor and painter, and the center of a free spirited group which prized naturalism.

Then last night, in harmonic convergence I stumbled on two films via Kanopy (if you don't know this free film service from your local library now you do) which had music and love at their centers.

Un Coeur En Hiver (A Heart in Winter) is the story of the love triangle between a young and beautiful violinist (Emmanuelle Beart), her older lover, and his business partner (Daniel Auteuil) in a violin fabrication and repair shop. But that is not really the subject. The subject is love and freedom.

Then I saw Pure, with a very young Alicia Vikander in her film debut playing a n'er do well, violent young woman who falls in love with Mozart, then procures a job as a receptionist at the symphony. She has a wild affair with the married conductor who then abandons her. Much trouble and many reversals ensue.

All this against the backdrop of live music returning to the Hollywood Bowl this week, where Gustavo Dudamel is conducting a series for front line workers. Gustavo is leaving at least partially for Paris--I don't blame him. The news today that Europe is reopening very soon has lifted my heart.

Magazzino Italian Art Museum is a captivating outpost of passionate collecting

Private museums are all the rage. A month ago, Glenstone opened in Maryland. There’s the Broad and so many others worldwide.

But Magazzino Italian Art Museum seems an outlier. It took me a year to finally have a Sunday to get up to Cold Spring. I had hoped for a better show of leaves along the Hudson River train route, but like everywhere else, global warming has pushed back on nature. For at least the second year in a row, there were only muddy browns and golds with the occasional red pop to remind us of what we were missing.

Derived from the collection of Nancy Olnick and Giorgio Spanu, the largely Arte Povera works at Magazzino were lovingly collected with intense focus and scholarship. Arte Povera really becomes understandable at this museum, its motives less murky. Having been lured by post war Torino and north Italy and then tumbling headlong into Sicily and Puglia these last years, the art had special resonance for me.

Margherita Stein was Arte Povera’s champion in Italy and she has passed the torch to the Olnick/Spanus with white heat. Architect Miguel Quismondo has designed a home for them in nearby Garrison and they asked him to carry on with the museum. Having only seen exterior shots of Glenstone’s gray pavilions and coming upon the (smaller) Magazzino gray pavilions, I was slightly put off by the austerity. Once inside however, there is a warmth and logical spaciousness that felt in keeping with the art.

An hour and a half long series of short films hosted by Germano Celant who coined the term Arte Povera at the entry is too long for one go, but 15 minutes will give you the necessary tools to approach the art. No wall labels of course (my pet peeve) but the small booklet you are given at the entrance is a pithy port to the artists and their works.

Celant explains the crucial animating theory of this group, largely a sixties reaction to industrialization and the loss of nature and natural elements. Taking their cues from water, air, land and fire, the primitive elements revered by the Greeks, as well as the animal kingdom, this self-organized Italian group juxtaposed the work of man and the work of nature in novel ways. The point, a very contemporary one, is that we are losing our way.

Alas, until Marisa Merz’s work was ‘exhumed’ a few years ago at the Whitney there was little attention paid to the concurrent work of women. Merz--husband Mario was more closely associated with the group—is here represented by works that captivate for their “warmer” delivery system.

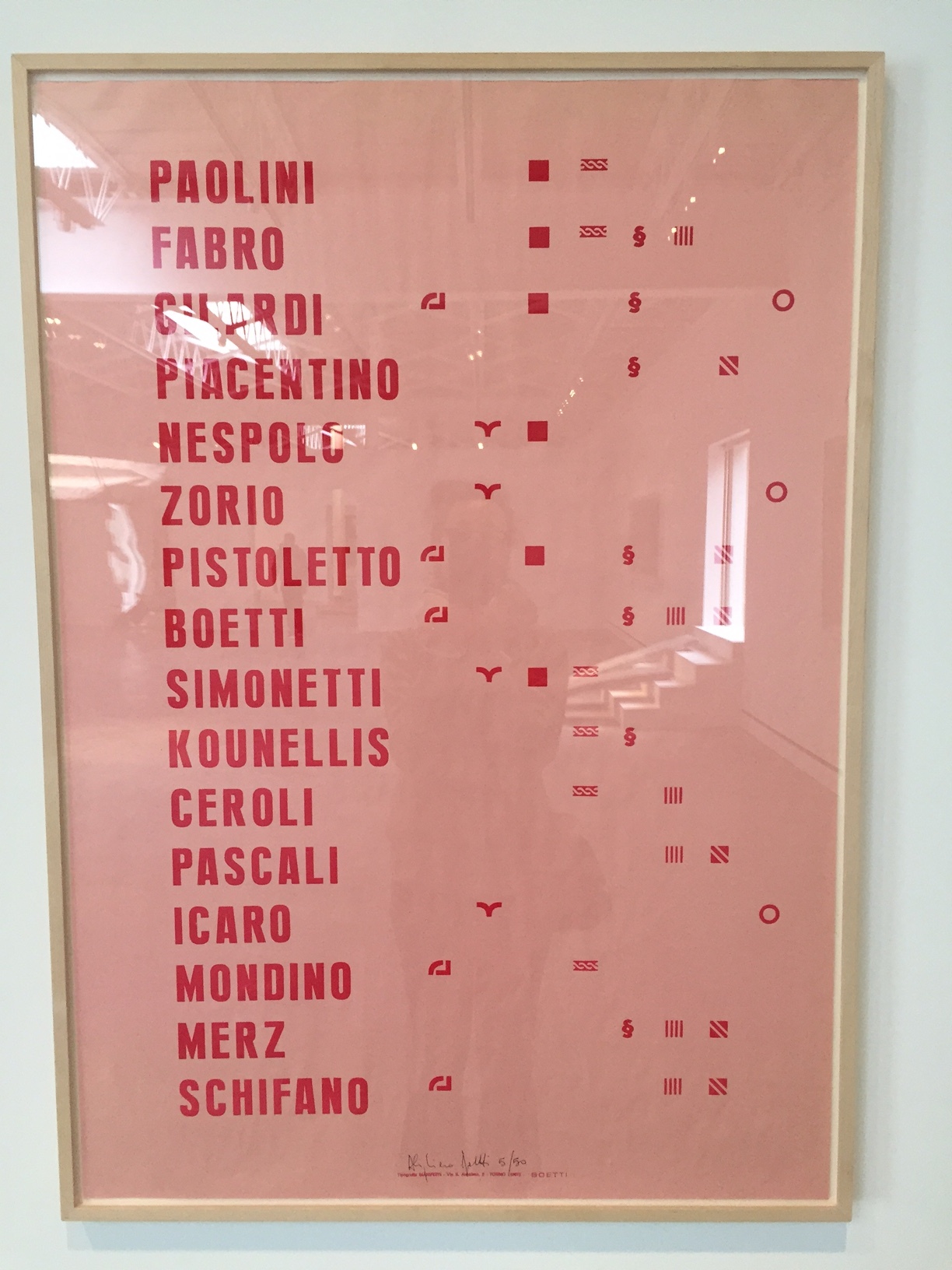

Workers and students were unusually aligned, especially in Europe during the late sixties and the art reflects a rejection of the status quo, then more oriented towards Pop and Minimalism. Other groups of Italian artists were seeking a different way out of the postwar but the Poveristos (my coinage) including Michelangelo Pistoletto, Marco Anelli, Alighiero Boetti, Luciano Fabro, Pino Pascali, Jannis Kounellis, Giuseppe Penone, Giulio Paolini marched to their own drum.

The Olnick Spanus also support contemporary Italian art, some currently on view at the Italian Culture Institute and the exhibition, which closes this week, makes a good pairing with the works at the museum.