Not long after his friend Germano Celant’s death Christo now follows. Christo taught us how to see things with fresh eyes, to notice things we may have passed many times by adding something that transported it to another realm. A lake is not just a lake (Iseo, Italy) a fence not just a fence (Running Fence, California) a bridge not just a bridge (Pont Neuf, Paris) a path not just a path (The Gates, Central Park) a building not just a building (Reichstag, Berlin) and so on. He was about to teach us a monumental arch was not just an arch (Paris Arc de Triomphe). Here at Lake Iseo in 2016 he taught us how to Walk on Water. His nimble, creative audacious eye and spirit will be missed.

Feat Of Clay; my story for Air Mail News

I sleep nude so that I make myself believe you are here.

Many kisses, Camille.

Most of all: don’t betray me anymore!

These intimate words come from a letter the sculptor Camille Claudel wrote her mentor and lover, Auguste Rodin, from one of the many hideaways he found for them during their tempestuous, decade-long relationship. He, prodigiously talented with an imposing blond beard, and she, more than 24 years younger but headstrong with blue eyes that missed nothing, were alternately obsessed, inspired, and tortured by each other. After years of devoted work in his bustling atelier and her emergence as a significant artist in her own right, Camille, his feroce amie, was in despair—Rodin was unwilling to leave his longtime companion Rosa Breuet.

From Adjani to Binoche and Back Again

Some may recall Claudel from the melodramatic film interpretation of Isabelle Adjani as the youthful artist filling her satchel with mud and pounding it in a frenzy, or from the more restrained performance of Juliette Binoche as the older, tragic Claudel. There are also operas, musicals, ballets, plays, novels, academic studies, and potboilers that depict this larger-than-life duo.

Others are likely more familiar with the Musée Rodin in Paris, which, due to Rodin’s later support, has a gallery devoted to Claudel’s work, though the wall labels which identify her as “Sculptress, Student, Assistant, Mistress” have a sang-froid that is far from the reality of their relationship.

The youthful artist filling her satchel with mud and pounding it in a frenzy.

No such qualifiers appear in the museum that bears her name in bucolic Nogent-sur-Seine. Here Claudel is the main event, not an appendage (the Musée Camille Claudel has just reopened, one of the first French institutions to do so following the coronavirus closures).

The enterprising historic city in Champagne reclaimed its teenage resident while also paying tribute to her first mentor Alfred Boucher. After an hour’s train ride from Paris, a visitor enters a welcoming contemporary addition—attached to the revamped Claudel family home—and is met by the muscular bronzes and intricate marble and clay sculptures that mark the late 19th century.

The museum secures Claudel’s reputation as a singular talent from a rigid era when women were not allowed to tackle subjects that were considered unfeminine, or even smoke in public.

The sculptor Camille Claudel at work, 1887.

Enfant Terrible

As with her sculptures, a twisted armature underpins Claudel’s story. A wild child who often escaped to the nearby forest, she was fascinated by primitive rock formations and collected clay, defying the bourgeois expectations of her quarrelsome family and her class. Her mother was particularly resentful of her mercurial temperament and artistic ambition but her father, who adored her, recognized her talent and intelligence and made sure she was tutored alongside her brother, which was unusual for the time. Her father also reached out to the French sculptor and friend of Rodin, Alfred Boucher. After seeing her surprisingly accomplished autodidactic work, Boucher prompted the family to relocate to Paris. Claudel was enrolled in a small academy because the Beaux Arts strictly refused girls. In all ways, she fiercely resisted the life she had been brought up to acquire. Women were meant to be discreet and domestic; Claudel was neither.

Key experiences gave shape to her life just as boulettes of clay then covered her sculpture’s coils. Boucher insisted Rodin see Claudel’s work and agreed to take her on as a pupil. Very soon, though just 19, she was first among many assistants in his atelier. Her alluring manner captivated the 42-year old-artist and she soon became his model and lover. His “dulled existence,” he confessed to her in one of many revealing letters, “burned into a bonfire.”

Women were meant to be discreet and domestic; Claudel was neither.

By circling around the pair of lover-colleagues as Rodin required of his sculpture students—a crucial final, technical step which helped bring out the movement and interiority of subjects—we see the transactional nuances of their relationship. She offered a close eye and ear on his work; that she also awakened him sexually is impossible to miss. He brought her connections to sources of funding and to the Salon where she had to be exhibited to get commissions. Despite her intense pride, and her love for him, Claudel understood that the surest path to recognition was through the patronage of a powerful man.

Their work was conjoined as closely as their bodies and though some pieces are similar, their different perspectives are telling: A man buries his head in a woman’s breast (Rodin); a man kneels and encircles a woman as she lowers her head to receive his kiss (Claudel); a woman crouches in a coil as if to protect herself (Claudel); a woman is splayed and exposed over a mound (Rodin). Her early work is often conflated with his, but her romanticism and his more flagrant eroticism—a liberty only male artists could take—is apparent.

Falling Through the Cracks

Hidden fissures began to surface in their liaison as they sometimes do in stone. Claudel agonized between her need for guidance and her resistance to being swallowed whole. She may have been the apprentice, but, cannily, she pulled away and traveled to England. Rodin was desperate. On a pretext, he pursued her—in vain. Taking advantage of the fleeting imbalance, she drew up an audacious contract which spelled out what he must do to continue to see her: she would be his sole pupil and lover, he would support her and her work, they would be married and, in an uncharacteristic nod to her bourgeois upbringing, the proof would be a professional photograph in her best dress.

In teaching her to bring out the essence of a subject, Rodin was, in a way, his own worst enemy. As she carved and molded, drawing remarkable expressiveness from inert material, it was as if she was also bringing herself fully to life. Claudel was not content to stay in her box.

In teaching her to bring out the essence of a subject, Rodin was his own worst enemy.

“Have pity, cruel girl, I can’t go on,” Rodin wrote. Despite his passion and admiration for her, the pre-nup was consigned to oblivion. Caustic cartoons she sent to him, depictions of a hapless Rodin trapped by Rosa, projected her anger. Another more poignant missive from her brother Paul, who had become an influential—and largely absent—poet and diplomat, reveals that Claudel also had an abortion.

Determined to assert her artistic and spiritual independence, she fled their folie a deux, even though leaving Rodin meant certain financial instability and the loss of critical attention. The Claudel specialist Anne Riviere, in a companion film at the museum, says, “In this desire to escape…his footprint, Camille Claudel invents…a way of making small sculpture big.” She began using rare materials like onyx. “It’s not at all Rodin,” Claudel proudly wrote Paul.

Losing Her Marbles

Though she kept the studio Rodin rented for her—money was indeed a problem—her new, intimate style was on display. Swirls and waves surround nude women frolicking or gossiping. In La Valse, a couple entwined in each other dance. Despite her repeated ardent supplications, the ministerial authorities refused marble for this piece, citing its display of “sexual organs which are too close.” A work like this was a slap in their faces.

She returned to the larger work, concerned with being marginalized as “decorative.” Her compelling Age of Maturity details a young woman grasping in vain for a man in the clutches of an older woman. The Goodbye, a woman struggling to escape a block of marble, is Rodin’s answer. These allegorical pieces show that Claudel and Rodin were still emotionally if not physically attached. Her Clotho, a mythological crone with tangled dreadlocks, reflects her increasingly precarious state of mind, the high-strung young girl now a woman showing clear signs of erratic behavior. Though Rodin agreed not to further agitate her by seeing her anymore, he worked tirelessly behind the scenes to help her, a ringmaster bereft of his high-wire act.

But still the commissions did not come. With only the rare show by her loyal dealer, she became ever more paranoid, fearful that Rodin and his allies were stealing her ideas. She moved again and barricaded herself, not bathing, barely eating, muttering as if possessed. She burned his letters. She destroyed many of her sculptures.

A work like Claudel’s was a slap in the faces of the authorities.

The neighbors complained. Fearing she would harm herself—and ruin the family reputation—Paul had her forcibly committed. Her father was devastated, her mother relieved of the burden. After a stay in an asylum near Paris, with war coming, Claudel was moved to another facility near Avignon. She implored the family to let her come home, or, failing that, to move her closer to them as even Paul hardly visited. But there was never an adequate response. And she had lost any meaningful advocates. Claudel spent a total of 30 years in close confinement, not sculpting, a sentence considerably more violent than she was. It’s as if the art had somehow contained the madness. She died, alone and abandoned, at 78.

Some think Claudel a victim of Rodin, others of a neglectful family, still others of her instability. Unquestionably, Claudel was a victim of her time. Just a few years after her death, in 1943, there was an explosion of female artists making their own way.

For too long, Claudel’s artistic reputation, much like Vincent van Gogh’s, was muddied by scandal and the tragic dénouement. According to Odile Ayral-Clause, a biographer, “The critics who condemned her for not being able to create a style [distinguished enough from Rodin’s] failed to understand that her battle was focused in a different direction.” The Musée Camille Claudel instead celebrates her native talents, novel choices, and incipient feminism. In Nogent, Claudel is surrounded by vibrant flowers, rushing waterfalls, charming allées. In Nogent, all her life is before her.

Photo of Camille Claudel by Cesar, courtesy of Violaine Bonzon-Claudel

Man Ray's wife Juliet's desk in Paris

This is the desk of Juliet Man Ray, the former dancer, model and Hollywood hopeful Juliet Browner who married Man (they had met in an LA nightclub) in 1946 in a double wedding with Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning. He was a Jewish boy from South Philly (ne Emanuel Radnitzky), she a Jewish girl from Brooklyn (she is pictured with the violin in the wood frame). On the desk you can see a gold cast of Man Ray's famous lips, a mini one of his irons, and other bibelots of his. I visited with Julie in Paris at their studio where she still lived on the Rue Ferou when I interviewed her for a PBS film about Picasso, she was every bit as theatrical as I had imagined and still carrying a torch for her husband who had died in 1976. They are buried together at the Montparnasse cemetery. Recently, the Gagosian exhibition of his work in San Francisco brought this all back to me.

John Chamberlain

This image of John Chamberlain in Sarasota on a poster from a show he had at the Margo Leavin Gallery in LA in 1988 always made me smile. Chamberlain, who this week appears on a 1980 video interview loaded by Hauser and Wirth from his Sarasota studio which looks like an automobile parts factory, is one of my favorite artists who had a signature style that never seemed to get old. In the vast spaces of #Marfa and Dia Beacon, his work is shown to particular advantage.

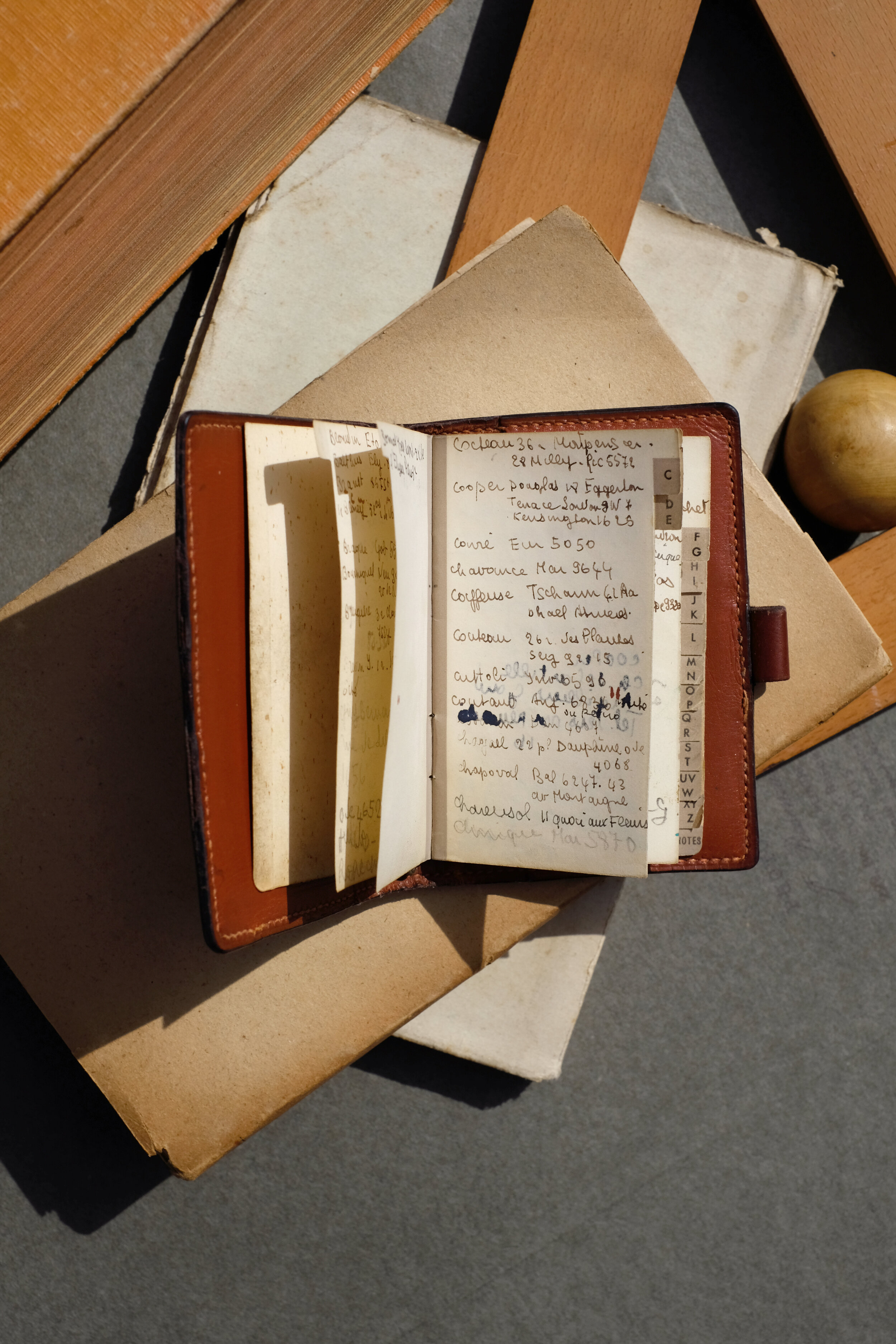

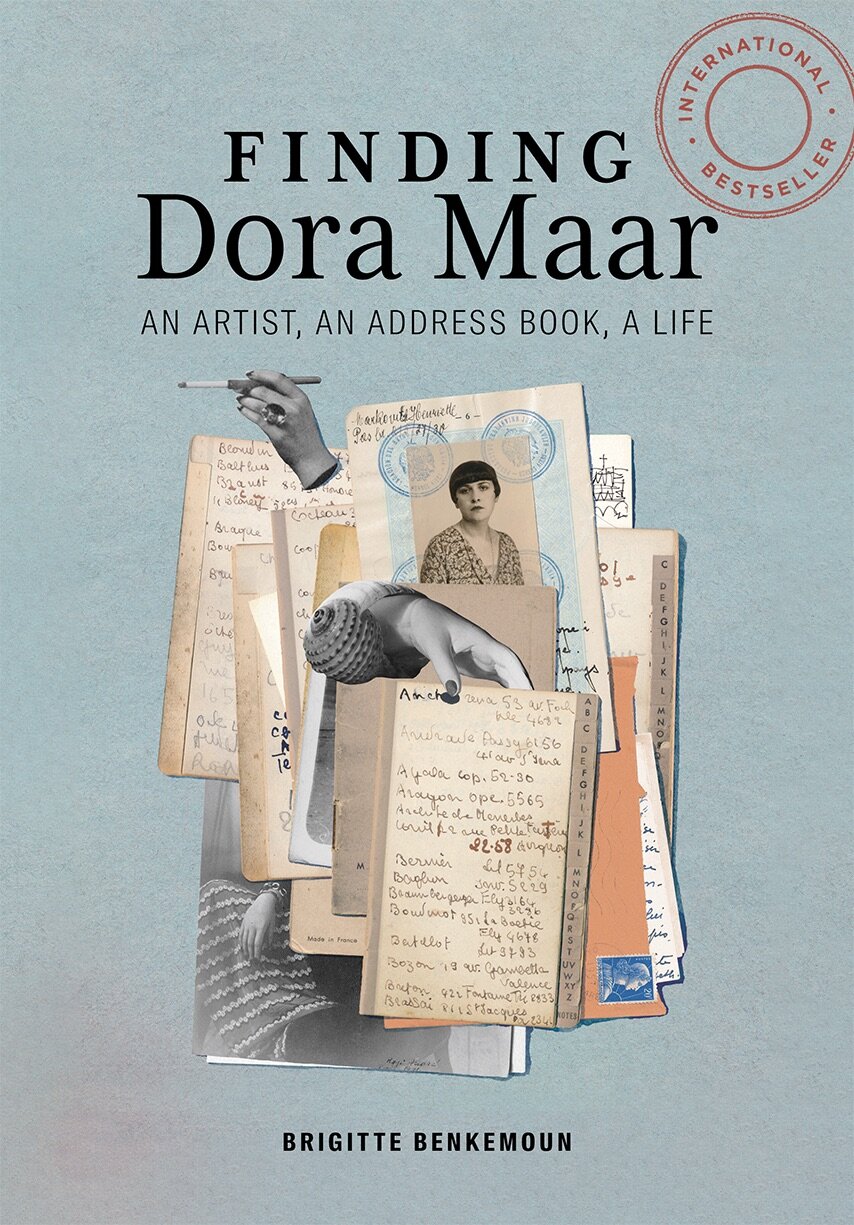

Finding Dora Maar-an Ebay purchase leads to treasure

We've all had the fantasy of being able to know what is inside the private diaries, letters, or yes, address books of celebrities. Brigitte Benkemoun's husband bought a replacement Hermes agenda on Ebay ( I happen to know these very well, I still have a desk black one with my initials and a small pocket red one similar to the one her husband was looking for though mine are consigned to a file cabinet now when I cruelly abandoned them first for Filofax and then the Contacts section of my iPhone). When it arrived, she was overwhelmed to discover the names of very famous French artists, poets and writers of the 20th century like Balthus, Brassai, Breton, Cocteau, Eluard--along with a plumber and architect and a hairdresser. It did not take her long to learn it was the agenda of none other than Dora Maar, known principally as the Weeping Woman model for Picasso and his lover for many years who was devastated when he abandoned her for Francoise Gilot (and others) and became a religious recluse in Mesnerbes, Provence. Benkemoun imagines the relationship Maar might have had with each entry, often importing her own conclusions when facts do not present themselves, but it is still a very engaging and often moving promenade down memory lane. The book has been published by the Getty, where the retrospective of Maar's important work as a photographer and artist was shown, exhumed first at the Pompidou. I had my own chase of Dora Maar and treasure her letters to me.

A haunting De Chirico image depicts lockdown

This image of Giorgio de Chirico's 1913 Ariadne from the Metropolitan Museum-- one of his iconic pittura metafisica painted when he was newly ensconced in Paris during what is considered by many critics to be his most important and productive year--has been haunting me during the time of Covid. De Chirico who had spent his early years in Greece, was himself haunted by the Greek myth that tells of princess Ariadne abandoned by her lover Theseus on the island of Minos after he had slayed the Minotaur with her help. He had a heightened sensitivity to his surroundings as he had been forced to move frequently with his mother and brother during his childhood and adolescence. The somber colors of the empty piazza, sun-washed but shadowed, the neo-classic Italianate colonnade, the desolate woman turned away in pain, the signs of life--a train and a boat-- out of reach on a far horizon, are all delivered in very flat paint with the theatrical 3D perspective of a raked stage and speak to his sense of dislocation. De Chirico embraced architectural imagery to get at the very heart of this disorientation and isolation in a poetic way that was totally original. His juxtaposition of unlikely subjects and objects set the path for a new genre of painting--Surrealism. Even though Ariadne is depicted sarcophagus-like, to me, she is more evocative of the way I feel when I step outside of lockdown and see our empty streets and deserted buildings than any other work of art I've seen. Though the painting was not on display when the Met was forced to close, my hope is that they will put it front and center when our situation improves to remind us to be grateful for art and for life. Thank you Artists Rights Society for allowing me to post this symbolic image.

Giorgio de Chirico, 1913, Ariadne, Metropolitan Museum of Art, © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

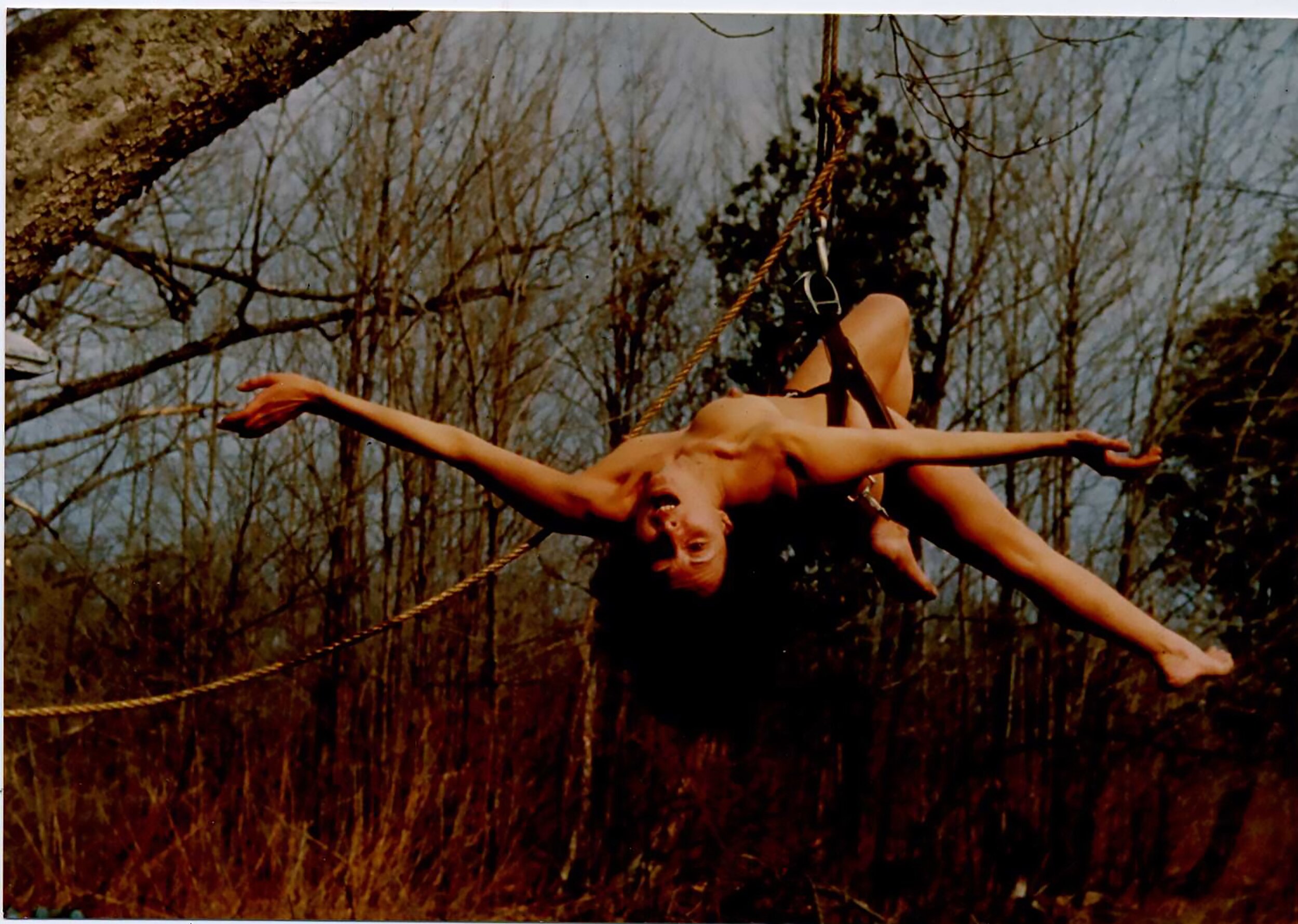

Carolee Schneeman and Ana Mendieta joined by their bodies in nature

Carolee Schneemann and Ana Mendieta who met on a panel in 2011 shared some basic instincts about their bodies in nature and otherwise as instruments of artistic power. Both were iconoclasts, very much their went their own way resetting boundaries. Schneeman was well known for a feminist performance piece pulling a tape out of her vagina. Mendieta was known for burning her silhouette in a ring of fire. (And for her tragic end out the window (pushed?) after a violent argument with her husband Carl Andre.)Now they are reunited in an online exhibition coming on April 30th by PPOW and Galerie Lelong showcasing some of this startling imagery that will surely once again wake us up as isolation begins to draw down our emotional resources.

Photo credit: Antony McCall 5 x 3 1/2 in. (12.7 x 8.89 cm) Courtesy of the Estate of Carolee Schneemann, Galerie Lelong & Co., and P·P·O·W, New York

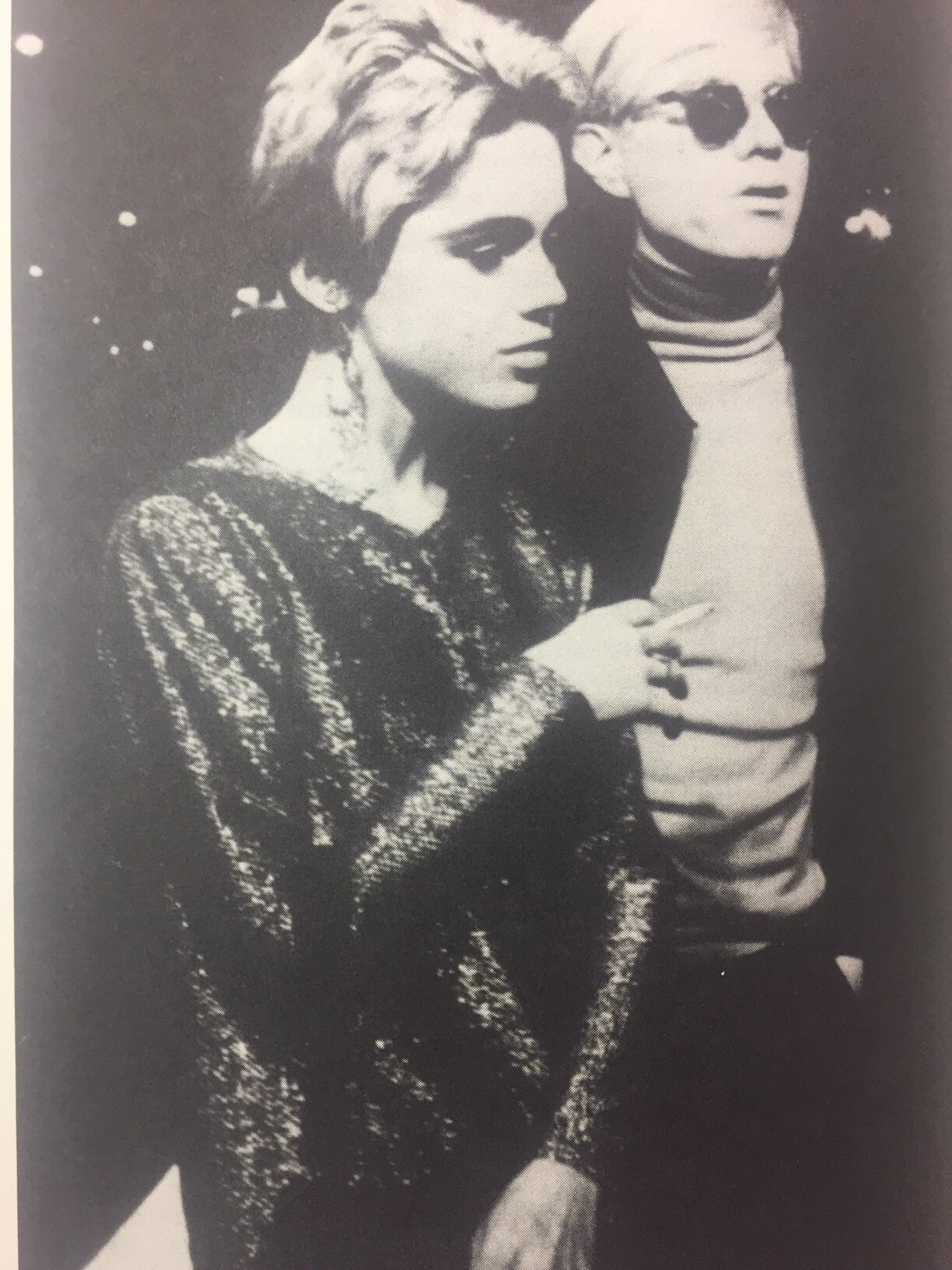

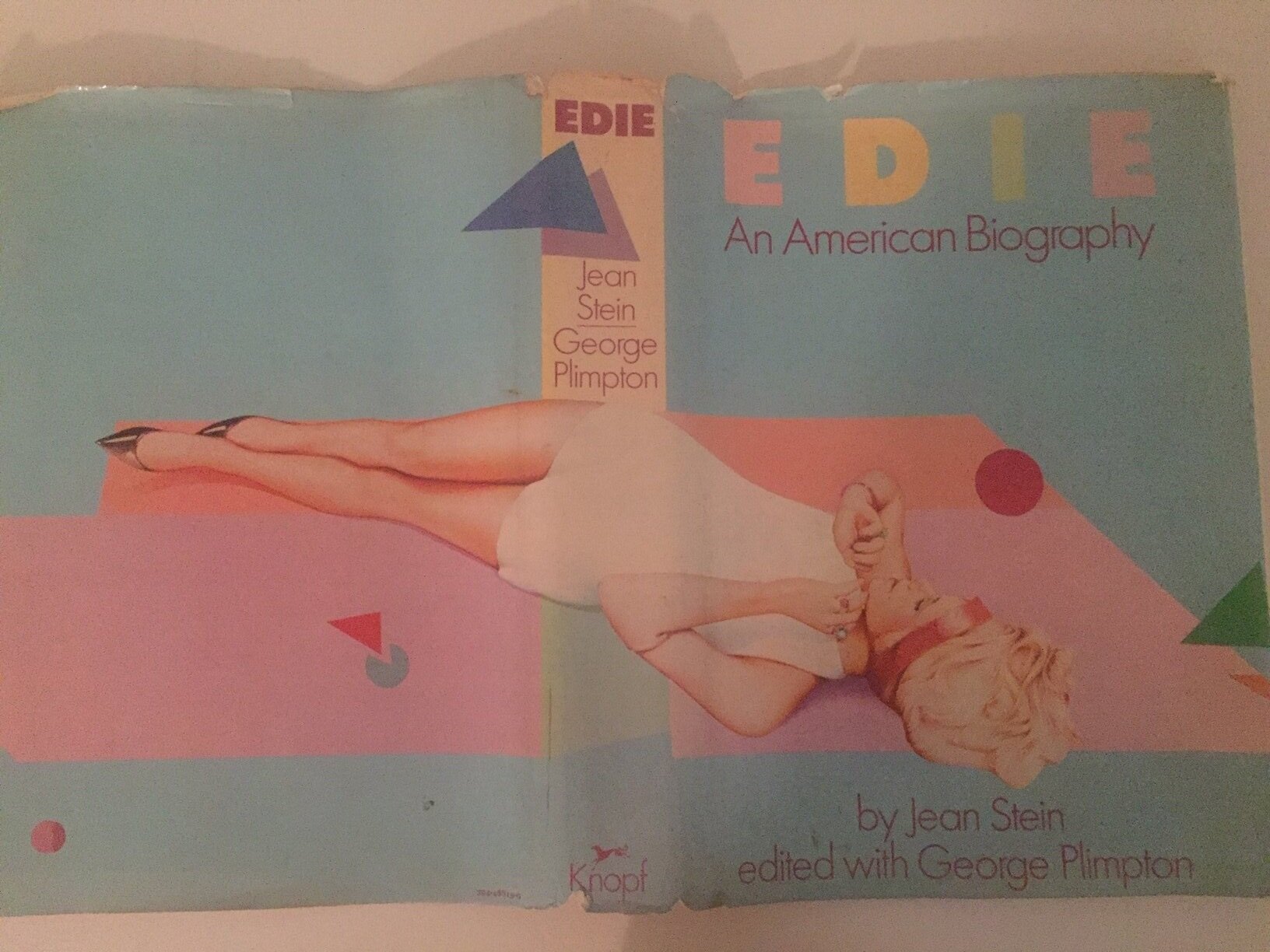

Remembering Jean Stein's illuminating bio of Edie Sedgwick

While I eagerly await my copy of Blake Gopnik’s new Warhol biography, I went back to Jean Stein’s riveting portrait of Edie Sedgwick and her world (old line WASP wealth and then the Factory), Edie, that appeared in 1982. Stein who was both of the world (a Hollywood daughter) and its excellent observer (via the Paris Review and George Plimpton, who edited this book) captured on-the-record oral histories that are still astounding in their you-are-theredness. Walter Hopps, curator, museum director, art dealer, nurterer of so many West Coast artists is on the record as are Truman Capote, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, denizens of the Factory, and of course, Warhol himself. Edie flamed brightly, erratically and died at the age of 28 of an overdose, joining a few of her other siblings who had not made it out of their twenties. Stein jumped from her window at the age of 83, which now casts an even more somber shade on this tragic tale.

Photo copyright by Nat Finkelstein, Used with permission of Nat Finkelstein Estate; Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgwick outside Lincoln Center

Dana Schutz and mothers under the time of Covid

TGIF some might say, the end of another long week under the shadow of Covid and chaos. This image of Dana Schutz's, 'Waterfall', a large charcoal drawing from 2016, seemed apt to me today. It's a mother and child, Schutz's brilliant version of a Madonna and Child or in ultra-contemporary terms, a mother who probably has spent the last week juggling her work, her children, the house, and keeping everyone safe. Schutz had a show of new work opening in London at the Thomas Dane Gallery in early June, I hope we will somehow get to see the latest work of this audacious and extremely talented artist. Image courtesy Petzel Gallery.

The San Francisco Maritime Museum: a WPA fantasia

The story of the San Francisco Maritime Museum, a hidden San Francisco gem, is not just one of architecture and design although that is what pops when you walk in the subterranean Ghirardelli Square-adjacent entrance. Looking out over the historic seafaring vessels of the Hyde Street Pier and the crescent shaped beach a visitor is struck by the graciousness of this temple to the history of West Coast Maritime History, rich with exhibits that speak of the life of the people who made their living at sea. Built in 1939 jointly by the WPA and the City of San Francisco as a bath house, the museum is part of a National Park Service Maritime Historical Park that highlights the city's connection to the sea. The museum, over 20,000 square feet, is.an astonishing example of the power of the federal government when it’s functioning as it should be and could be a model for a new federal program that could enlist the help of the many talented but struggling artists during the time of Covid. This enlightened project came to fruition over more than four years under progressive American artist HilaireHiler who not only did the phantasmagoric first floor murals of the Lost Cities of Atlantis and Mu but was also a costume designer and color theoretician, a polymath who had befriended Henry Miller Anais Nin and Hemingway at the Jockey Club in Paris where he had been the host. His glorious ceiling Prismatarium” is an ode to color theory in which he proposed that color and the human psyche interact to enhance creativity. Other artists like Sargent Johnson, a black sculptor who did the tile murals who had been associated with the Harlem Renaissance and Richard Ayer who supervised the second floor murals and flooring and who engaged vibrant Shirley Staschen, who had also done the WPA murals at the nearby Coit Tower, were also enormously talented. This treasure is a model of public engagement which is on scant display today under the current administration.

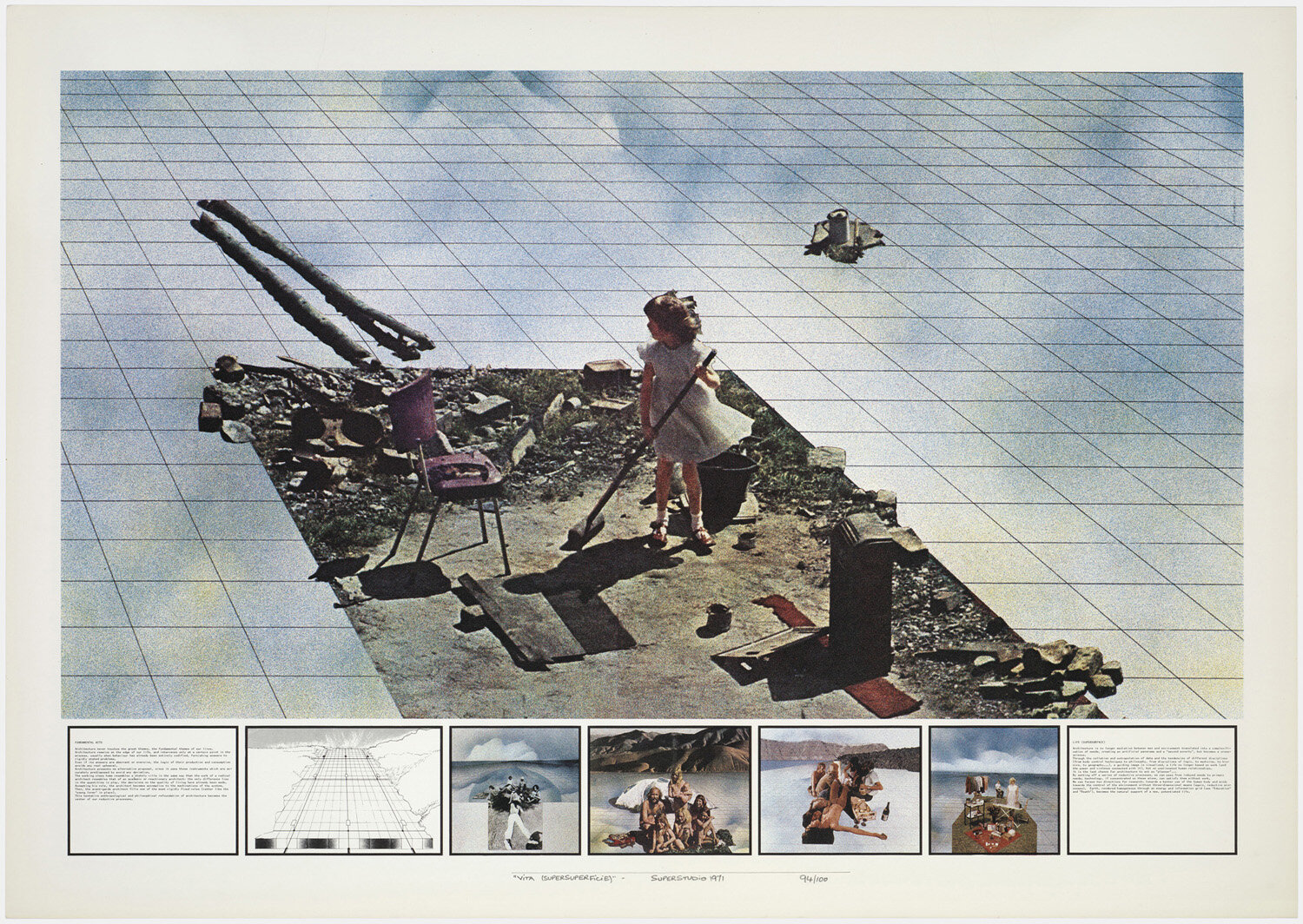

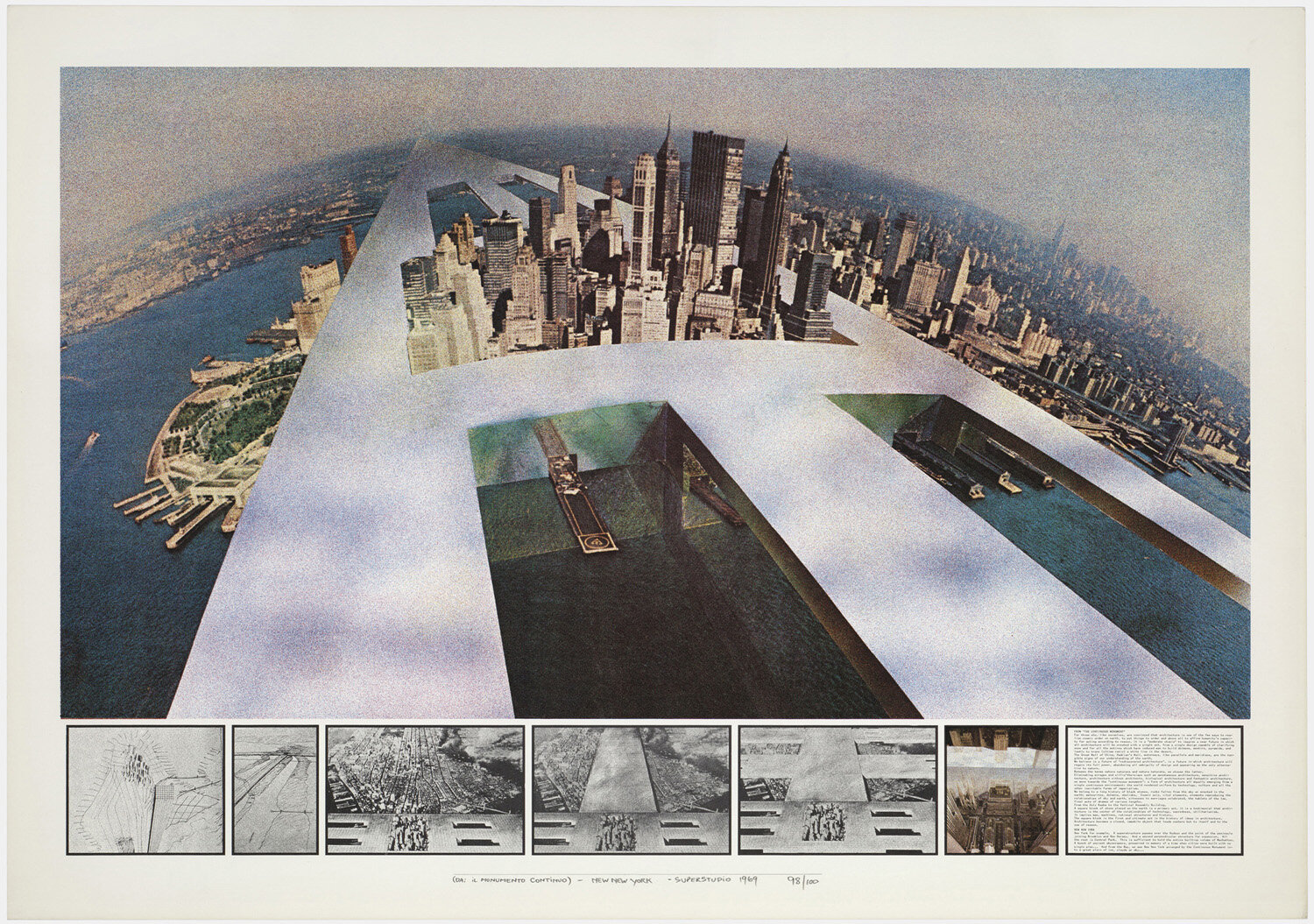

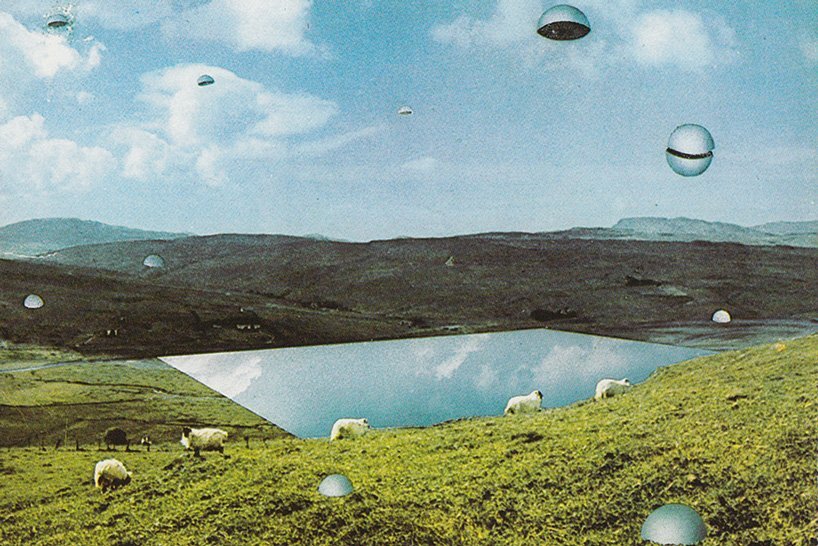

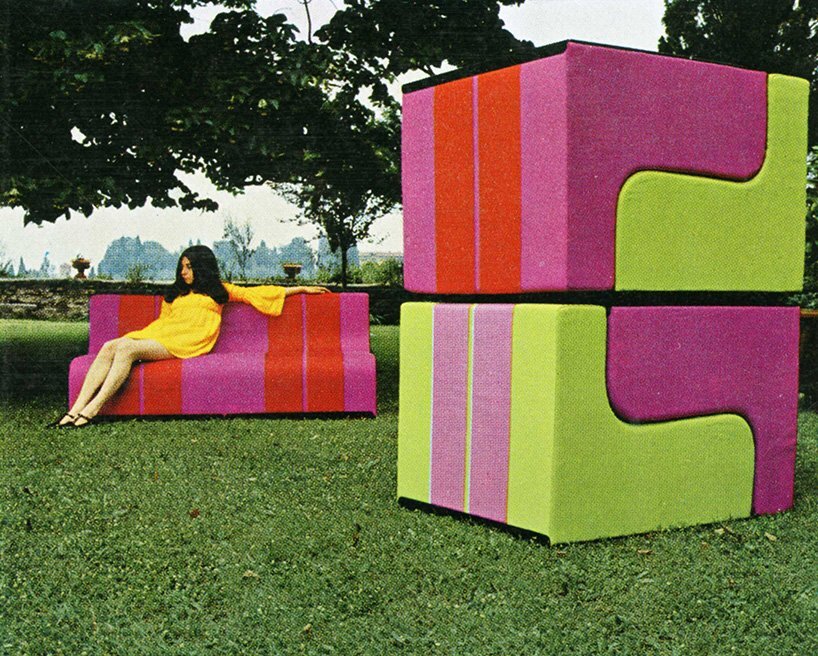

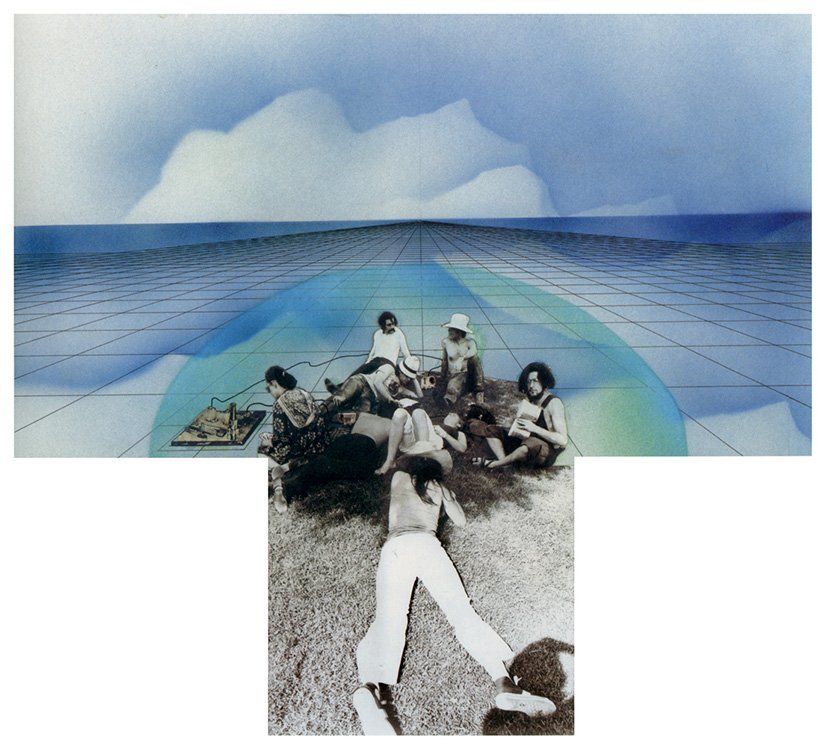

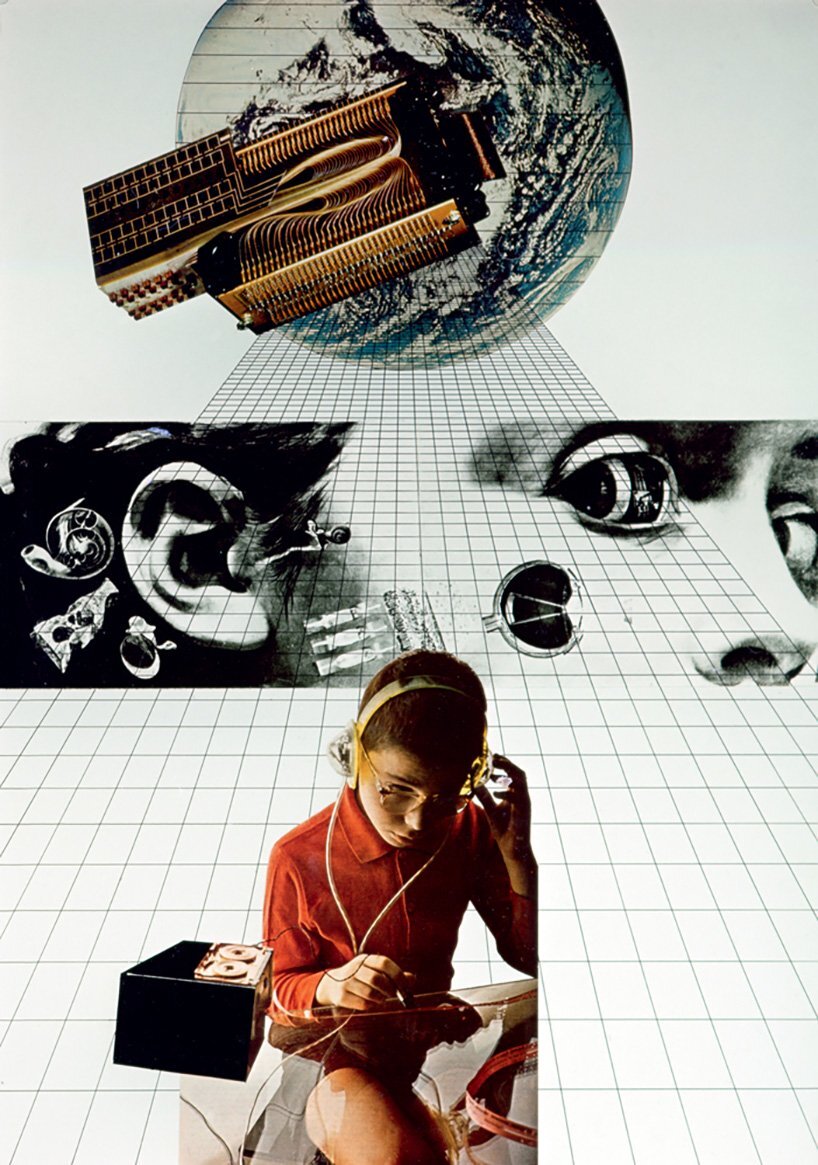

Superstudio: the Italian radical design group saw the future

In 1972, the architecture design collective Superstudio arrived in New York along with many other Italian designers for MoMA's Italy: the New Domestic Landscape exhibition. At the time, they were labelled 'radical'. In 2016 the Maxxi Museum did a 50th retrospective of their work which had presented 'an alternative model for life on earth...a final attempt of design...for a society no longer based on work and on power and violence.." By 2020 they can no longer be called radical but rather prescient. Their theories about the need to reduce waste, overproduction, superfluous design, consumerism, and rather to encourage living with nature, to take only what we need with us on our backs, to look to the sun, the clouds, the stars, to live without possessions on a grid and simply plug in wherever you are now resonate in a contemporary way. "Life will be the only environmental art", they once wrote. In this time of Covid, their message aligns with the message of Earth Day 2020.

Images of Gli anti fundamentali, Self Portrait, Poltronova sofa all by Cristiano Toraldo di Francia; Images of Il Monumento Continuo and Atti Fondamentali Vita - Supersuperficie. Pulizie di primavera, by Superstudio, all courtesy Fondazione Maxxi, Roma.

Olafur Eliasson and the Serpentine team up for Earth Day

Today I'm supporting the launch of 'Earth perspectives', a new artwork conceived by Olafur Eliasson for Earth Day 2020 whom I had the pleasure of meeting and working with at a Rolex Mentors and Proteges a number of years ago and understood then how big he thought and how much he cared about the environment and because this year, the beloved Serpentine Pavilion which always pointed towards the future will not go up in London. It's comprised of nine images featuring nine different views over the Earth. The work explores how maps, space and the earth itself are all to a certain extent construction, which we all have the power to see from other perspectives, whether individually or collectively.

To create a new world view...

1. Stare at the dot on the Earth about ten seconds.

2. Then train your focus onto a blank surface.

3. An afterimage appears in the complementary colours of Eliasson's visual.

4. You have projected a new world view.

I'm sharing this work as part of the @serpentineuk 'Back to Earth' initiative, a new, multi-year project that invites artists, scientists, architects, musicians, and more to make work that responds to the climate emergency.

The Earth viewed over the Simien Mountains, Ethiopia

One of the rare places in Africa where snow falls regularly, this range is part of the Ethiopian Highlands, known as the 'Roof of Africa'.

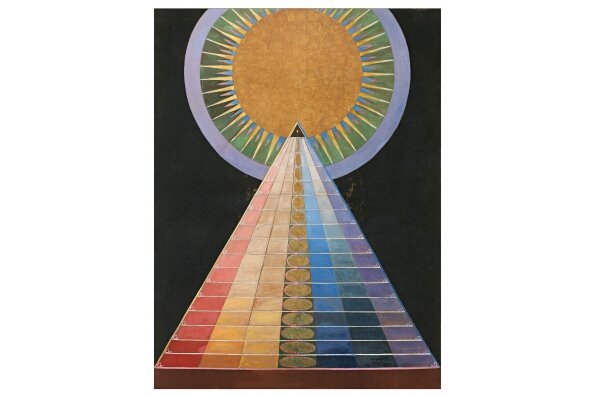

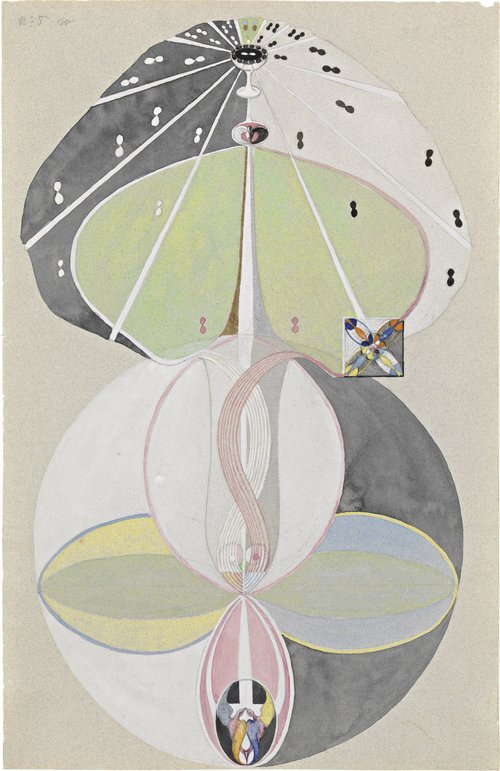

A new film about groundbreaking Hilma Af Klint

When the Hilma Af Klint show was at the Guggenheim, the lines were around the block for this largely unknown artist as if for the Rockettes at Christmastime. Hilma turns out to have been a hidden rock star of art and a new documentary (put their hash tag) advocates most strenuously for her place in the artistic firmament. Hilma was fascinated by the scientific advances of her century that dialed down on the invisible: radio waves, atoms, quantum theories. She had a parallel belief in spirituality and communication-especially Theosophy- and founded a woman’s group of avid séance-practitioners. She painted, in dreamlike colors, enormous canvases and series that were hidden away until a few decades ago. By not having exhibited in her lifetime, she was not credited with her important breakthroughs in abstraction. (put The filmmakers name) puts her work ahead of Kandinsky’s. So many artists were breaking through at that time, it is hard to point one single finger. Still, the film is a fascinating look at what artists can create in isolation (artists take heart!), and reminds us that neither art fairs, nor galleries nor museums (MoMA rejected her work) can be considered the arbiters but that artists’ own passions are what drive the greatest creations.

Allan McCollum's collection of Everything is Going to Be Ok

According to his website, conceptual artist Allan McCollum 'has spent over fifty years exploring how objects achieve public and personal meaning in a world constituted in mass production" but to me that is a a pale, somewhat narrow definition of this non-conformist. I remember reading in his oral history at MoMA that McCollum who once worked as an art handler there said about the then Picasso-centric collection, “I remember laughing, thinking the museum should be laid out like “Before Picasso,” “Picasso,” “After Picasso,” “Like Picasso,” “Unlike Picasso,” “Sort of Like Picasso.” and he made me laugh too. MoMA has pointed out that McCollum has a vast collection of screen grabs of moments where characters reassure each other that 'everything is going to be ok". It takes a certain prescient genius to have somehow foreseen our current, self-isolating Corona pandemic--and also a sense of humor. McCollum was due to have two shows, one at the Miami ICA and another at Marc Selwyn's gallery in NY, both of which are now in exhibition-purgatory. Let's hope we get to see them.

Helen Frankenthaler's youthful joy

Last Friday, the news broke that the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation had donated 5 million dollars to artists affected during the Corona shutdown. I had seen this image of Helen in Provincetown, a young artist herself. Helen was in the midst of a great flowering of her talents at the Days Lumberyard a space she and Motherwell had rented for the summer of 1961. Take a look at the joie de vivre oozing from this photograph: the perfect little doorless Fiat convertible with straw seats, Helen in a sleeveless top or perhaps a bathing suit, waving a scarf, you can feel the warmth and the excitement of her life. Somehow this felt open and inspirational to me, the very opposite of shut-in.

Image: Frankenthaler in Fiat “Jolly,” 622 Commercial Street, Provincetown, summer 1961. Courtesy The Dedalus Foundation, Inc.

Ruth Asawa postage stamps showcase this inventive artist

I visited with Ruth Asawa’s family in San Francisco a few years ago in the house Ruth and her husband lovingly put together and which her son, Paul Lanier a talented artist also, maintains in the spirit of his inspirational parents. Despite a rugged childhood being interned at Santa Anita racetrack as a Japanese American Ruth went in to study with Josef Albers at Black Mountain and became an educator who devoted herself to raising awareness of the arts in schools along with her own wire sculpture practice. The USPS has now issued a set of stamps of her work and if you need to snail mail while you are social distancing you can order these online. Each message will then have a touch of Ruth’s uplift to carry it on its way.

Suellen Rocca, an art heroine of the sixties, dies

Suellen Rocca, a founding member of the Hairy Who Chicago art collective active in the sixties has died. Her art was feminine and feminist at the same time. She repurposed advertising imagery, female icons and color in a distinctive way. I love the way she and her art appear in this image as one. . When asked about the sources of her imagery, Rocca cited “the cultural icons of beauty and romance expressed by the media that promised happiness to young women of that generation.” I don't know if the show of her work due this summer in Vienna will be held. She deserves attention. Images Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery.

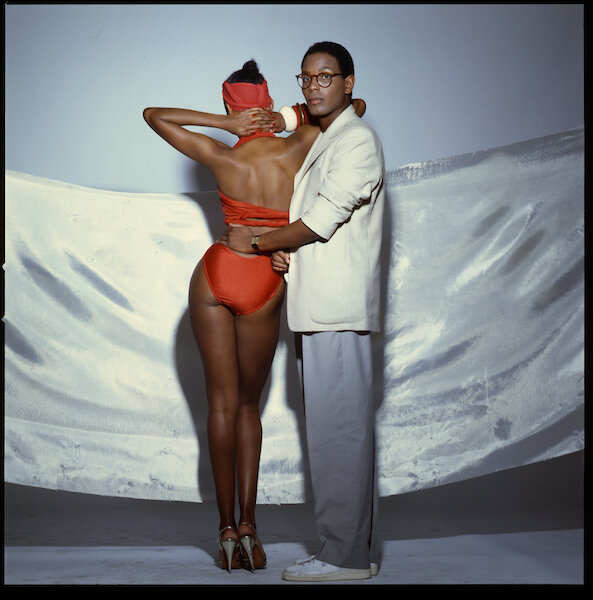

Willi Smith at the Cooper Hewitt

Despite the recent kerfuffle over the controversial ousting of its director, the Cooper Hewitt has a new lively small show tucked away on black designer Willi Smith. Smith took his inspiration from the Street in the 70's when clothes were finally cycling out of a different kind of poor boy aesthetic. Smith designed for dance, for theater, music, combining genres, races, and classes. His loose fitting rompers and jumpsuits look particularly engaging in the chain-linked exhibition install by Sam Chermayeff. Smith's death at 39 of AIDS came at a time when many in the art world ranks were being decimated by the disease. Go to the Cooper Hewitt website as the show is alas now closed.

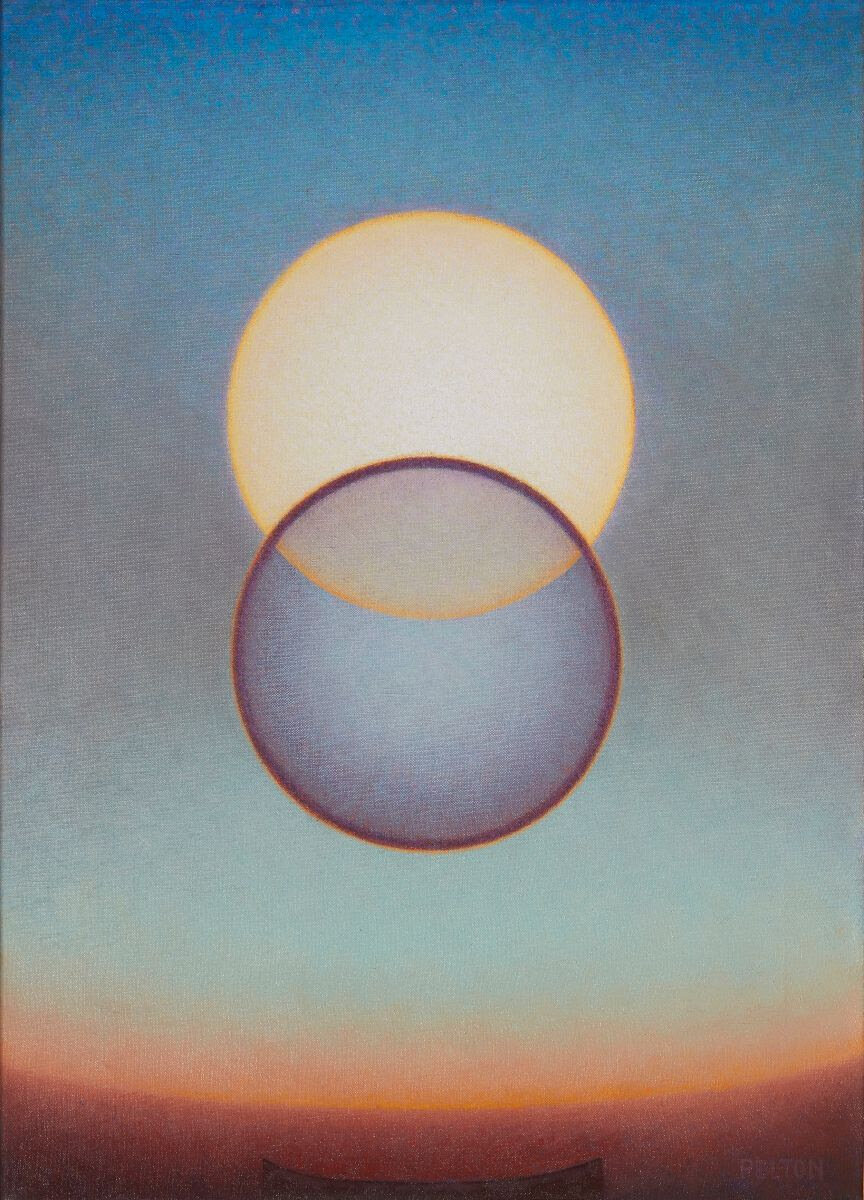

Agnes Pelton at the Whitney

Agnes Pelton, cut from similar luminous cloth as Hilma Af Klint, arrives at the Whitney in a time when meditative, transcendental work is a tonic. Though often lumped in with O'Keeffe she rightfully belongs to Water Mill, NY and Cathedal City, CA. She believed in a divine principal and portrayed emblems of higher planes of consciousness which we could all use right now. She worked alone, and was not known in her lifetime Here two example of her gauzy symbolist work. Go the Whitney website for more Pelton images now that the museum is alas closed.

Countryside-Rem Koolhaas on the hot seat

The reviews of Countryside have been unkinder than necessary. I found the vintage Technicolor graphics from China and Russia that Rem Koolhaas and team made into wallpaper, the undulating curtain with images that evoke the countryside from Marie Antoinette’s Hameau to Arcadia, inserts that ranged from hippie communes to gorillas, bathroom columns plastered with urban cowboys, Town and Country and Country Life magazine, Lego Sets and freestanding 19thcentury paintings a pleasurable and provocative riot of imagery and text (on the floor, walls and ceiling of the Guggenheim ramps). It was crowded and people were stopping to read, observe the plant life and tractor, watch the many videos. It’s as if Rem predicted that the Coronavirus would arrive and we would all want to flee into nature—which itself, he says is sorely compromised by climate change etc. It’s a perfect hike up the ramp into the Countryside. Go to the Guggenheim website for more images as alas the exhibition is now closed.