Did you know there was a Le Corbusier designed barge docked on the Seine in Paris? The boat was a project of the Comtesse Polignac and her friend Madame Zillhardt who gave the funds to the Salvation Army so they could better house the homeless. Corbu added pilotis, ribbon windows and a roof terrace. I'm not sure if our various agencies have ever considered refurbishing old boats as a solution to the homeless housing problem, but Corbu engaged in many socially conscious initiatives that had implications for the general population. The boat is currently being refurbished by a Franco-Japanese partnership after having sunk in 2018 when the Seine flooded. Quelle bonne idee!

Should Trump decide how our federal buildings look?

The White House has announced an executive order called "Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again" which would establish neoclassical architecture as the default for all federal buildings, e.g., courthouses, post offices. Will MFBBA become an acronym like MAGA indicating a time when the country was falling under the sway of a despot who wanted to remake an imaginary US to his own personal taste? Now that Trump has been exonerated in the impeachment trial he feels free to attack another element in the culture wars: how our world looks. Does anyone remember when Prince Charles tried this? There are very good reasons to have contemporary architects pay attention to context but that doesn't mean they have to conform to a certain style. Its true mistakes have been made. But styles go in and out: a Paul Rudolph's Government Service Center in Boston, now endangered after being reviled for many years, is now newly beautiful in the eyes of many lovers of brutalism.

Kids City in Copenhagen

Copenhagen is at the top of the list of livable cities. Charming and also grand, the city is inviting and its citizens remarkably welcoming. Now the Danes are laying claim to the title of the city being the best place in the world for kids to live. Their deserved hubris is documented by a new exhibition at the Rem Koolhaas designed Danish Architecture Center. Kids City boasts slides and rides in a kind of real life Legoland and allows kids and grownups alike to understand the elements makes this creative metropolis work so well.

The Luxembourg Gardens host a temporary day care

The Luxembourg Gardens hold a special place in my heart. During my junior year abroad I had to cross the gardens on my way back and forth to the Rue Vavin every day, generally munching a croissant, in one direction, a chausson aux pommes in the other. The gardens are royal, the palace with its military guards is often the locus of art exhibitions, and are extremely well maintained. You can play tennis, or jog, or just take in the flowers and statuary on chairs and benches which are not fixed, moving them around as you like. There is never any trash on the ground. Now, a temporary nursery by Djuric Tardio Architects built with the modular concepts of Jean Prouve has been built in the gardens apparently to accommodate children whose own nurseries are under construction by the city of Paris. Though this feels odd in the midst of this royal splendor, all credit must be given to the French for prioritizing 'creche's' as the day cares are known, as they always do. The French are protesting losing their benefits which far exceed those of the US but in this case even a royal garden is enjoined in the quest for making the working lives of families possible. The building will stay in the Gardens for two years and then be moved to the 13th arrondissement. It took 5 months to build and cost around 2 million euros. Vive la France.

St. Andrews University-the Ivy League suffers by comparison

The dreary Scottish days of unremitting rain finally stopped and the sun shone at a most magical place, St Andrews. This university, home of Will and Kate and other more distinguished graduates like JM Barrie overlooks both the storied golf course and an unexpected beach. It puts the Ivy League Architecture though very nice to shame and I suggest to all parents in light of the college payoff scandal and those who were considering similar subterfuge they look to Scotland for a truly elegant bang to their buck. I don’t think they require the SATs!

Zaha Hadid's Riverside Transport Museum in Glasgow

The dark exterior of Zaha Hadid’s Riverside Museum in Glasgow belies an acid green interior which bathes the vintage cars and old steam trolleys in an oddly generous and unusual light. The waterside transport museum comes after so many refined Mackintosh tea rooms and all white bedrooms and is the perfect jolt into the 21st century. This was one of Hadid’s last commissions and one wonders where she might have gone from here.

Harry Potter-land comes to life at the University of Glasgow

To come upon the University of Glasgow a thrilling, majestic series of cloisters, chapels, libraries and green quadrangles (at least the unremitting rain has that net benefit) is to feel as if Harry Potter himself will appear in cap and gown at any moment. The entire country of Scotland has re-branded itself as Harry Potter-land. Every bus or train tour is sure to take you by Potter sites where they filmed or have some kind of even remote reference. Apparently Rowling is issuing more books soon. Only the Starz series Outlander vies for a tourist’s attention. It was Charles Rennie Mackintosh who instead held mine.

Miss Cranston's Tea Rooms by Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Miss Cranston ruled the social scene in Glasgow in the late 19th century. In a series of tea rooms, one restored in Glasgow—The Willow Tea Rooms—another, the Ingram, restored and installed in the Kelvingrove Museum (a World Monuments Fund project) , a third at the new V and A in Dundee (which I preferred, with a more robust and less fussy integrity),all developed in time when temperance in the air. Mackintosh was himself an alcoholic but these rooms, among the first where ladies could gather unchaperoned, anchored his fanciful designs. In actual fact, his wife Margaret was a co-author of many of his spaces, but has naturally receded in historical terms. The city of Glasgow aims to bring her to our attention by featuring her work alongside his both in the tea rooms and in their (free) museums.

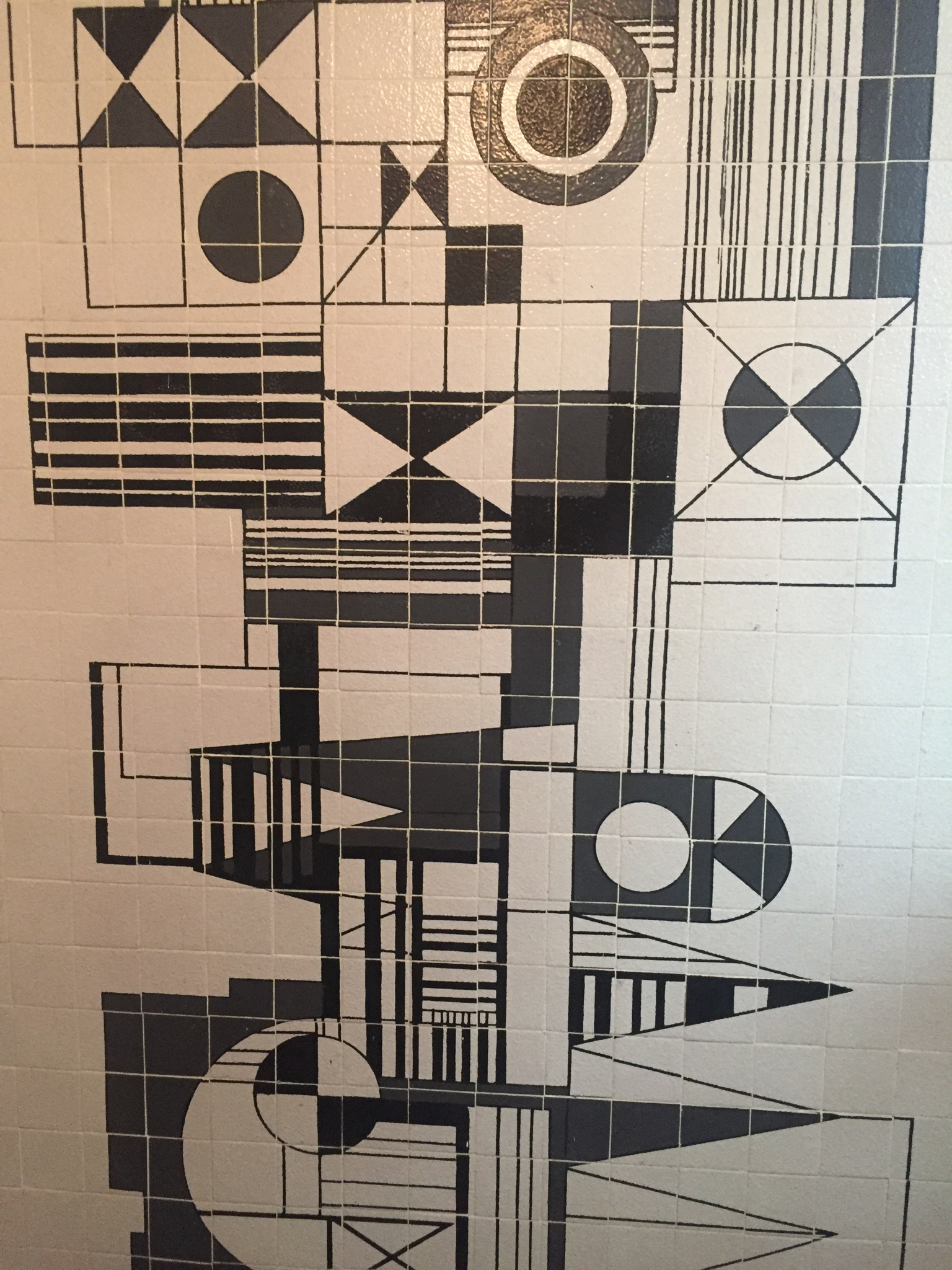

Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak, a Polish architect revitalized a city left in ruins

The very complete Patchwork show of the architecture of Polish woman Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak ended last week. In the early seventies my husband joined a posse of American planners and architects who went to Poland on Marshall Plan money to help revitalize the country. They found a bleak environment and harsh post war conditions. Grabowska-Hawrylak was associated with Wroclaw (formerly Breslau) as a student and as a prime mover of the reconstruction of the city along with a similar, domestic cell of architects and planners. At the Center for Architecture, a panorama of her built and unbuilt works told a tale of public housing, education, cinema, conservation, capitalism and socialism and a country left in ruins. Social Realism gave way to urgent needs of housing the population irrespective of theory. Prefabs were required. Residents jokingly called their housing estates The Principality of Monaco or Manhattan. A model of her Grunwaldzki Square project had been built out of Styrofoam and it was magnificent.

Photo: ,Courtesy The Center for Architecture, by Chris Niedentha

Bulletin from Brazil

Brazil has been much in the news. As if it weren’t enough that post-Olympic budget shortfalls, political corruption, Zika and crime had combined in a toxic brew, the recent election of Bolsonaro pointed up deep-seated philosophical fears and divisions much as the Trump election did in the US.

Brazilians in the creative sector have been trying to regroup, but in addition to the above they have faced devastating fires (the National Museum of Rio), burst dams, (Brumadinho adjacent to Inhotim art park), and the abolishment of the Ministry of Culture, which has been folded into a newly christened Ministry of Sport.

I finally returned recently to Brazil after a long absence. As a pre-teenage exchange student in the home of a wealthy Carioca family with whom my parents had briefly met and conspired late one night undoubtedly after too many caipirinhas, I had a decidedly one-sided view of the country. As a sheltered suburban girl, suddenly I was with a posse which had free reign—underage drinking and driving, dancing ‘till dawn on Ipanema. On the wild rides to mountain homes in Petropolis we passed favelas which made me mute— Brazil was my first third world country.

I returned ostensibly to study modernist architecture but my journey became a window into both politics and culture as a country’s built environment—and how it is respected— is closely aligned with the political imperatives of the day. In my view, this 20th century patrimony is as important as the pyramids are to Egypt. So many iconic structures are deteriorating and are without adequate fire protection. In Rio next year there will be a world architecture congress with government support which will address some of these issues—already a few of the most distinguished buildings are undergoing thorough, if protracted, preservation projects.

I arrived this time in Brasilia and went directly from the plane to drop my bags at the Niemeyer designed Palace Hotel, a quiet lakeside gem near the Embassy district. I had the impression of being on a stage set even though Brasilia is now a full-fledged metropolis. Inevitably, it is the show stopping Niemeyer federal buildings that still have pride of place. My first stop was to be the Alvorada Palace, the Brazilian White House, the Bolsonaro residence of only a few weeks’ duration. Military guards and street blockades warned that this would not be easy and, sure enough, even though I had given my passport number in advance (and Bolsonaro was in Davos), I learned that the palace, though previously accessible on certain dates, was now permanently closed to visitors. My architectural colleague (almost all my expert guides were organized by Superbacana) explained that, in his opinion, the house was Niemeyer’s most beautiful work in the city. I’m told this might change, but it was only the first of many heartbreaks of inaccessibility along my route

Nevertheless, my day with Oscar, as I came to think of it, was every bit as fulfilling as I had imagined. Brasilia is a resounding example of the political will of principally three men—Juscelino Kubitschek (President), Lucio Costa (planning) and (architect) Oscar Niemeyer— to build a utopian mecca for a new more central seat of Brazilian government in 1956 (it had been Rio)—in just four years. Though I generally am suspicious of superstardom in architecture, here I was grateful to have this body of monumental work on display. Yes, there were manifold issues around its construction in the middle of a largely rural province. As in the construction of Gibellina Nuova, Sicily, the visionaries marched to their own drum without consulting local inhabitants.

Highlights: on the Monumental Axis, the Itamaraty Palace with its splendidly thin arches, its central staircase, its Roberto Burle Marx garden; the National Congress with its pea green carpeting, brutalist hallway and starry-ceilinged legislative chamber, the Ministry of Justice with waterfalls emerging from its façade. On the residential axis, the elegant living spaces and muted colors of the Superquadras (these a true revelation), the brutalist, un-gated Mexican Embassy. (Our American Embassy has just announced a new project by Jeanne Gang. Thank goodness, as the walled, wired, hodgepodge mess there is an embarrassment. At least one good decision from the Trump State Department).

In anticipation of going to Salvador, Brasilia’s polar opposite, I took an Afro-Brazilian dance class at Steps. That revved me up for the multi-culti experience of that seaside city which keeps its clock—and its energy—on a time all its own.

Highlights: There is a Lele (Joao Lima) cathedral and city hall and other projects by Lina Bo Bardi, one in restoration (the museum) but others (a theater, a bar) in alarming stages of disrepair. I was very taken with the local branch of the Sarah Hospitals chain (LeLe was in the in-house architect), and a wonderful history museum, the Misericordia Hospital, evidence of the Portuguese wealth that existed when Salvador was an early capital. These are thankfully in pristine condition.

A contemporary architectural intervention into an adjacent palace made the Carnival Museum a dynamic space with video exhibits which—for the first time in my experience— give dance and music a founding place in the history of a country. However nothing was as thrilling as an actual afternoon Carnival rehearsal with Olodum, the largest of the Bloco Afros.

Though some claim they have become too commercial, their intense drumming and singing which revved up a crowd of locals and foreigners was entirely infectious and hardly disturbed by the defile of military police which marched through at regular intervals. ( In the town square, I saw other police routinely searching and harassing local youth. Is this a new Bolsonaro initiative or business as usual in Salvador?) Two new chic hotels are open near the waterfront (Fasano and Fera), but I stayed in the heart of the Pelourinho district at the faded but friendly Convento do Carmo which felt more in keeping with the city energy. Salvador was named one of the NYT 52 places to visit this year, but I would wait until fall as many things are under construction.

I was a lesser but still mournful victim of the giant dam disaster in Brumadinho as, despite pulling every string possible, I was not able to gain access to Inhotim, the marvellous contemporary art site just adjacent which, although not damaged, was closed in solidarity. I made lemonade by adding a stop outside Belo Horizonte at Pampulha, Niemeyer’s spectacular lakeside complex—again devised in a collaboration with Kubitschek.

Highlights: The museum, the church (it’s in restoration but I managed to get a peek at its famous mural), the open air restaurant, the Casa do Baile (Sanaa must have seen this one), the beach club, and the home he built for the Kubitscheks, which feels as if they might emerge at any moment, are once again vibrant examples of this giant of 20th century architecture who was able to think about intimate spaces as well as grand.

I practically wept at the haunting beauty of the twelve Aleijadinho soapstone prophets in Congonhas, and arrived in the colonial mining town of Ouro Preto. (You can still stay in an original Niemeyer duplex in the Grande Hotel with one of his signature winding staircases.). I happily lost myself in the cobbled streets of the colonial town and visited the three local museums—the Inconfidencia is an excellent intervention into a former slave prison. It wasn’t until I returned to the States that I learned that Ouro is another town also directly at risk from mine disaster as is much of Minas Gerais, once the wealthiest pocket of Brazil.

Arriving in Rio at the famed Santos Dumont airport was the first time I had a real chance to assess my vivid memories. The city is still so beautiful, where mountains meet the sea, but at every turn, the favelas remind of the societal disparities. (One even still bisects an extravagant private golf club.) Nevertheless, the display of modernist, art deco, and French inflected architecture is unparalleled and with the right guides one can access some hidden spaces that are an aficionado’s dream. I learned more about Lucio Costa and his Carioca school confederates Affonso Reidy, the Roberto Bros, Paolo Werneck, Jorge Moreira et al.

Highlights: We went to the roof of an adjacent building for a view of the famous Niemeyer-Burle Marx Ministry of Health which was at the top of my list (closed for restoration as so many projects are, alas), explored the hidden upper reaches of the Brazilian Press Association, the perfect reinstallation of the Burle Marx garden at the top of the (very private) IRB corporation Roberto Bros designed building.

The Instituto Salles was also partially closed for installation, but its outdoor spaces are elegant and well preserved in contrast to Oscar Niemeyer’s own house which, though technically in restoration by his family, is a mess. An expedition there with two intrepid architects who care deeply about its progress enabled me to see close up just how much is needed, and is not being done. Though I had written about the out of town Sitio Burle Marx, I was unprepared for its wild majesty and the many 17th century domestic structures left as Burle Marx inhabited them. The Sitio was apparently the scene of wild parties and gay life that garnered him quite a reputation at the time, but only enhanced the enchantment of this extraordinary space for me.

(Note well: There is a completely new oasis in the Leblon district, the Janeiro Hotel set to officially open in time for Carnival next month. This boutique heaven will certainly draw the smart set away from the famous Copacabana Palace. If you look left, you see the Corcovado. If you look right, you are facing Ipanema Beach. It has almost every service a larger hotel would have—and an especially engaging staff. At the end of a day of seeing many buildings in disrepair, it was particularly welcome. Anyone who is considering Rio—for example for the Architecture Congress in 2020—would do well to base herself here.)

In Rio, shorts is the uniform. In Sao Paolo people wear suits and build enormously high walled compounds. Brutalism reigns. (Again I was warned about crime, but experienced no qualms myself. One homeowner told me he had been held up at gunpoint in his shower and had left his absolutely primo brutalist Paolo Mendes da Rocha house in the care of his brother). Mendes da Rocha himself, now 90, is, however, apparently undaunted and still maintains his modestly located downtown office. Though busy , SP certainly has a less exotic, hothouse air than Rio.

Highlights: The projects of Lina Bo Bardi, the Italian architect who together with her husband Pietro commandeered the Brazilian art and culture world in the 1950’s and 60’s via the Museum of Sao Paolo, her stewardship of the museum and university in Salvador, their joint editorial supervision of their magazine Habitat, her truly egalitarian SESC Pompeia culture center and her own Casa De Vidro are still first class examples of civic and botanical engagement combined with architectural splendor (more soon on Bo Bardi). Proud homeowners welcomed me to their singular brutalist houses. Niemeyer’s grand Ibirapuera Park is vast and undergoing very slow renovation. Artigas and Cascaldi’s architecture faculty at the University is a majestic building but from my perspective, compromised by layers of apparently unrestricted grafitti. It’s in vastly better shape however than its counterpart architecture faculty in Rio.

Brazil has probably the greatest concentration of important 20th century architecture as anywhere in the world. Private funding for preservation is scarce, there seems to be precious little corporate support of these structures.

Mine was the only American I heard on this trip, and very little else. Argentinians were the few tourists I encountered. Many have been scared off, I imagine, by the onslaught of frightening front page news. The Brazilians are among the liveliest, most welcoming, citizens and their creative professionals among the most erudite. I urge Bolsonaro to reconsider his priorities. Brazil’s artistic heritage is one of its strongest suits and can only serve to deposit prized dollars into its coffers. I returned wanting to install ramps, winding staircases, philodendron. And a set of drums.

The Sea Ranch at SF MoMA: If you build it, will they come?

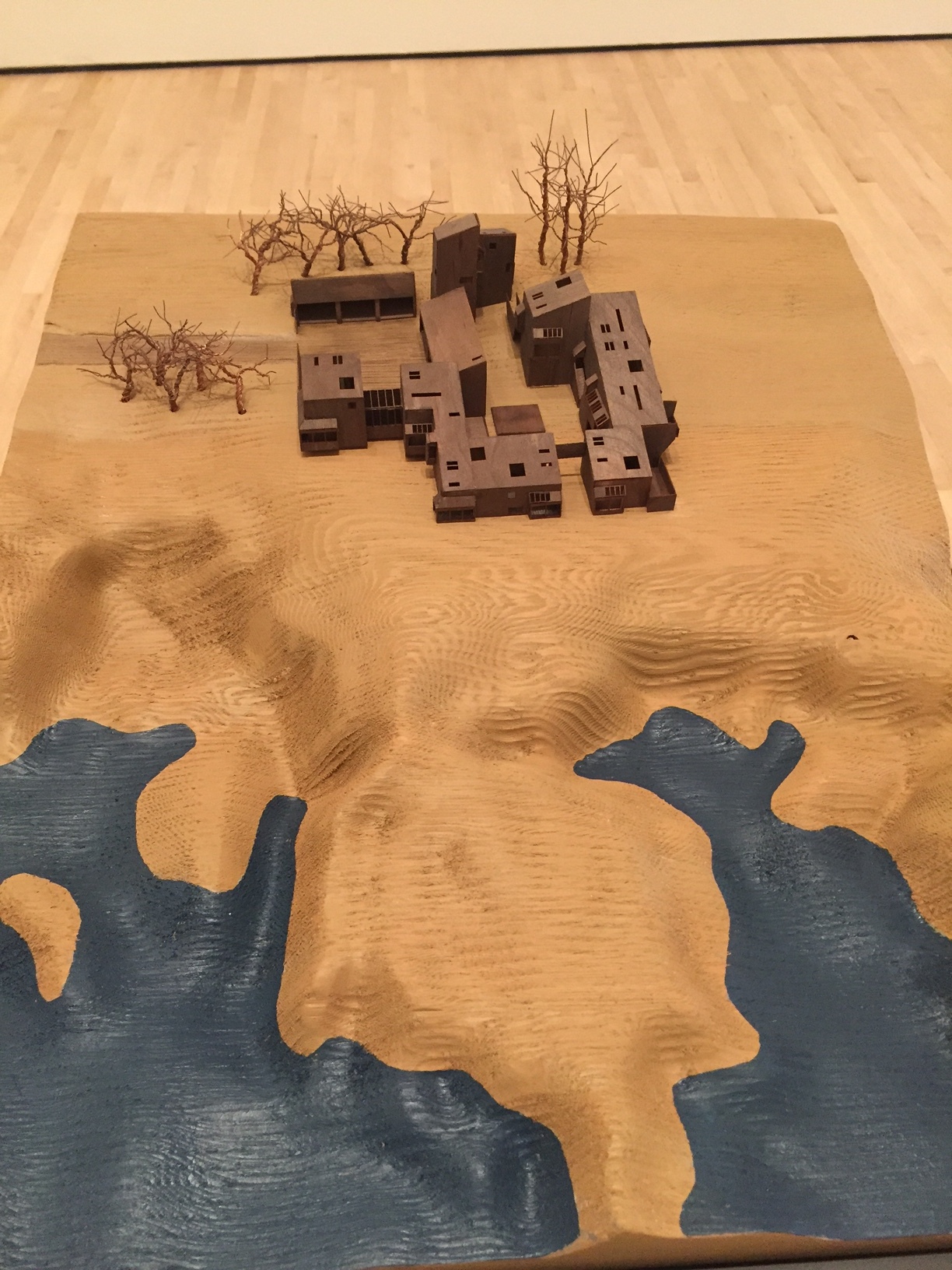

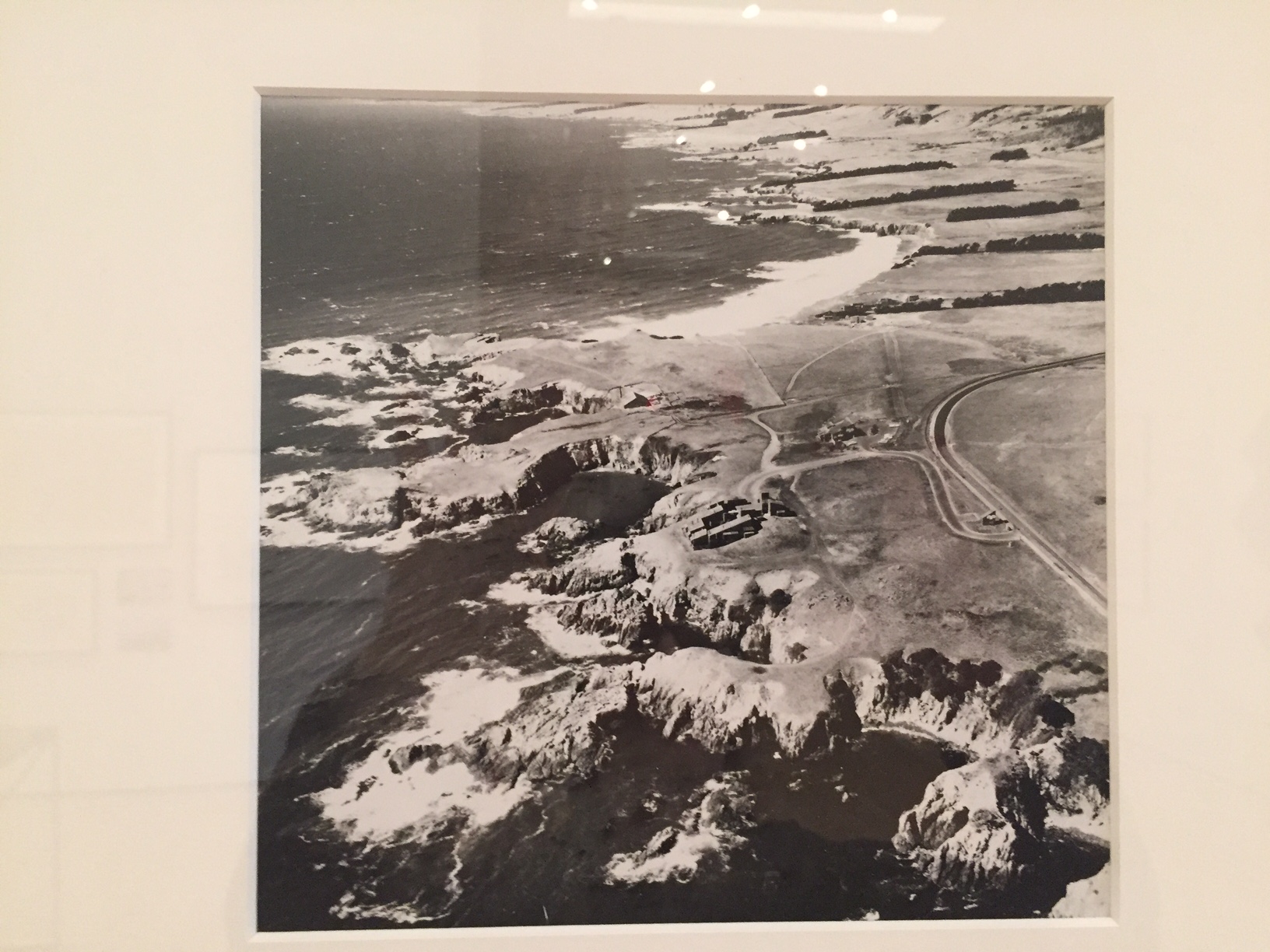

Sea Ranch, a sixties Utopian project by Bay Area architects and designers about 100 miles north of San Francisco, is now the subject of a tightly focussed exhibition at SF MoMA, and still exemplar of a remarkably sylvan development along ten miles of pristine California coastline.

The purchase of the land was organized by Al Boeke, an LA architect- developer in 1963 and was a hat trick that would never be allowed today as problems of public access to the ocean arose almost from the very outset. The powerful California Coastal Commission—which now regulates billionaires from getting their way in Malibu and other seaside communities— grew out of the divisive politics of getting the Sea Ranch underway.

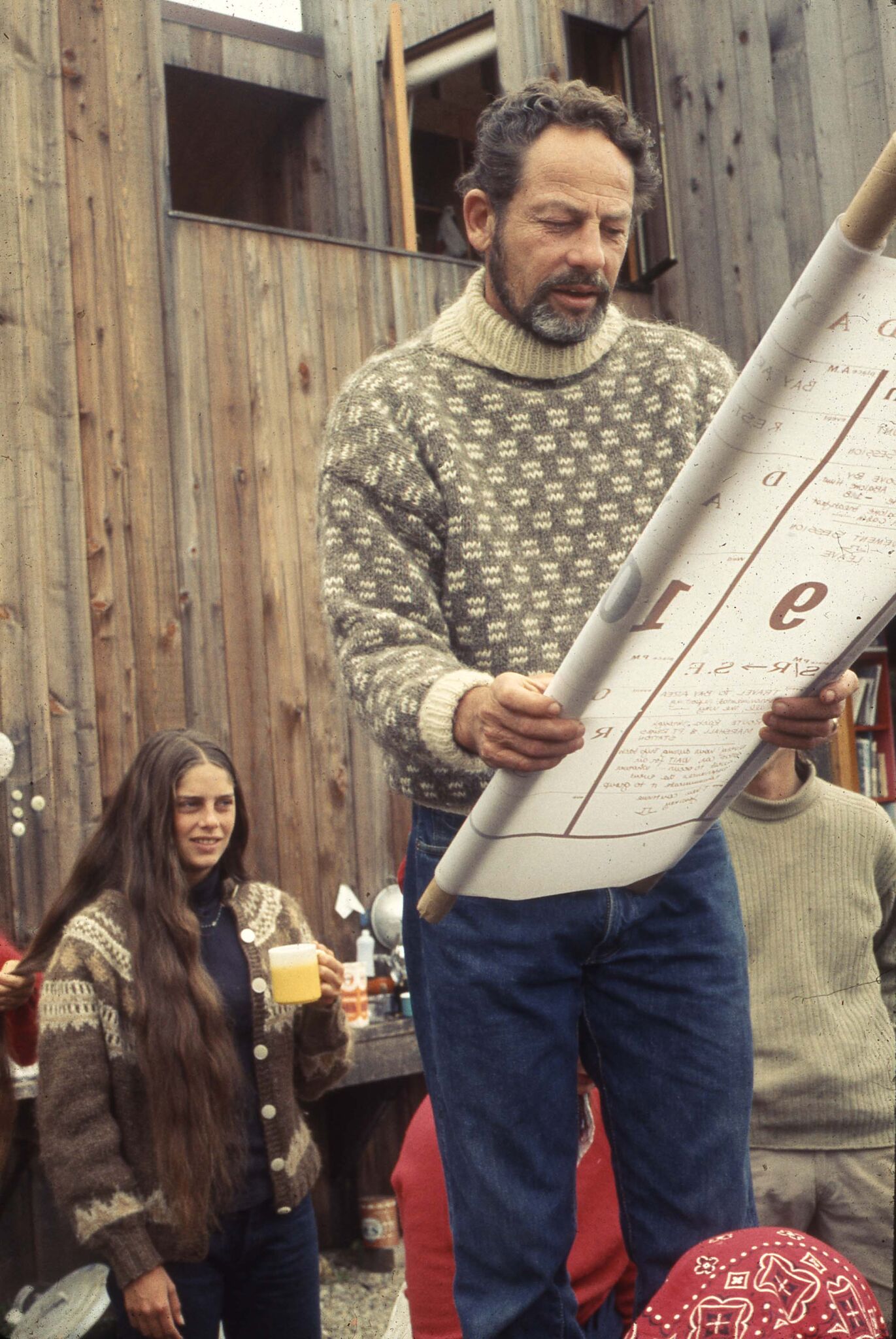

Larry Halprin, the opinionated landscape architect, was engaged to master plan the site and Joseph Esherick, Obie Bowman, Charles Moore, Bill Turnbull, and other architects and designers to create housing (the first condos) all out of unpainted redwood that would meld more naturally with the grassy, coastal landscape. Roofs had to have a specific slant. Bold graphic design and marketing by Barbara Solomon kept within the scheme. Originally, there was to be an escape from suburban style development, but when the concept didn’t sell well enough, more structures were added. Now there are over 1800 homes (many second homes or rental properties).

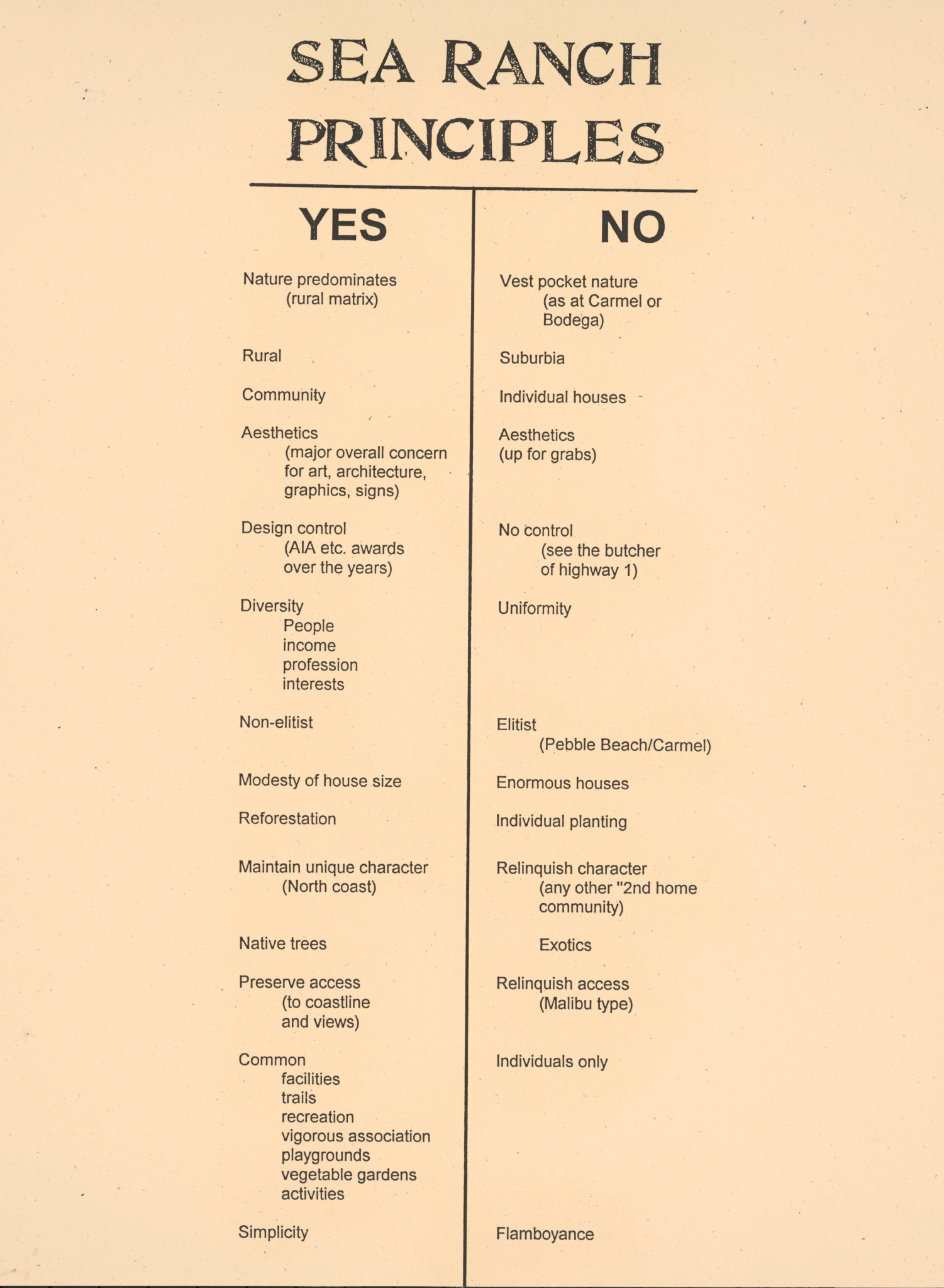

SF MoMA has built out the interior of a house within the exhibition gallery and it is under the weathered eaves you can catch a short film about the project with original participant interviews. As in Gibellina, Sicily, visionary but dogmatic planners were eager to influence the way we live our lives—see the list of dos and don’ts in my slide show (above). They were intent on making the development nature-and-environmentally friendly, yet ignored certain human foibles. The sixties and seventies were marked by this kind of futuristic ideation at a time when it felt like the world was indeed falling apart. Structure and planned community became a literal metaphor for trying to put back some kind of order into life.

The natural progression after seeing the show is the drive up to Sea Ranch where there are many vacation properties for rent and see what you think. Has it lived up to their prescription?

Monumentality at the Getty: an exhibition filled with solidity and whimsy

The Monumentality exhibition at the Getty Research Institute (in my opinion, always the venue of the great sleeper hits of Getty curatorial initiatives) is of a cosmic piece with the MoMA show on Yugoslav Concrete Utopias. It’s much smaller but it has as thesis that monumentality is not only defined by concrete but also other structures and natural objects that have a certain considerable mass and effect on the environment.

In particular it dials down on Los Angeles as a home to monumental structures that are more unconventional and opens one’s eyes to the very concept of monumentality.

It begins with Trajan’s Column in Rome, the Place Vendome copy in Paris, built, destroyed and rebuilt depending on the political whims of the French and their view of Napoleon, and Palmyra, Syria sites that are, alas, no longer with us.

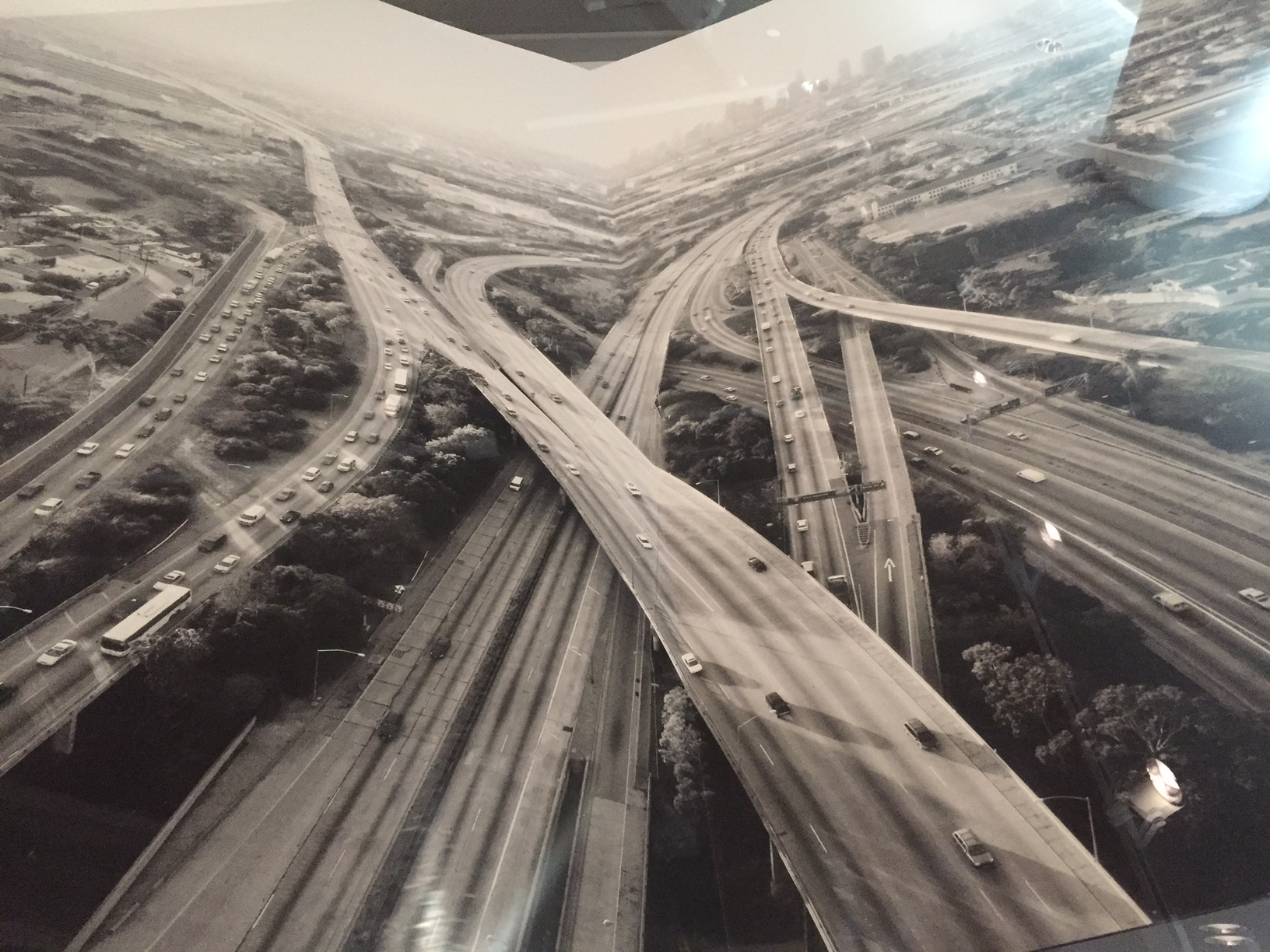

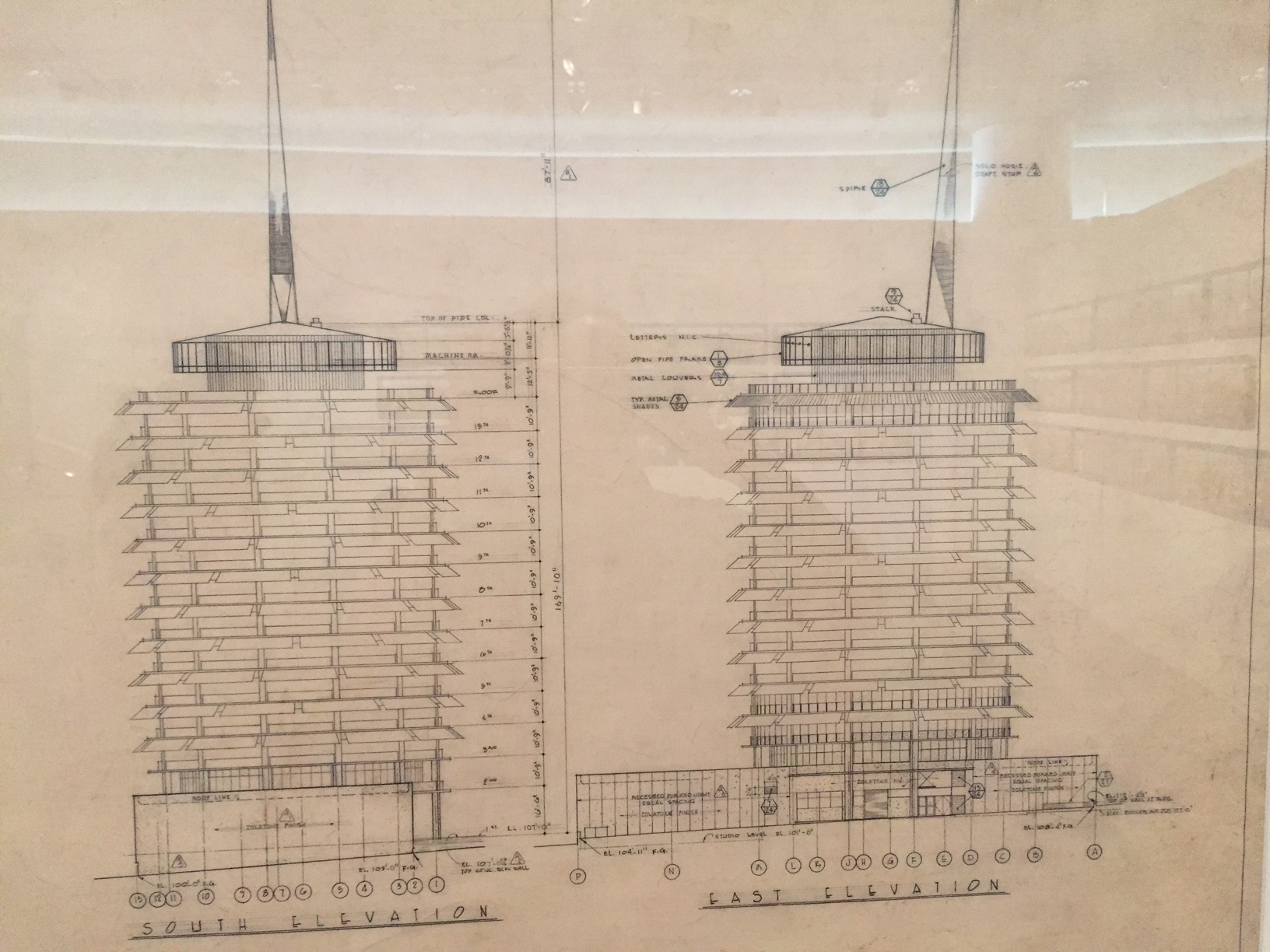

But it quickly moves on to things one might not have considered ‘monumental’ at the outset and by the end of the small but pungent displays make a convincing case that the infamous Los Angeles freeways, the LA River, Virginia Dwan gallery’s Earthworks show, the Capitol Records building, Tacita Dean’s riff on a JG Ballard paired with the Smithson Spiral Jetty, and the Moon itself are also ‘monumental’.

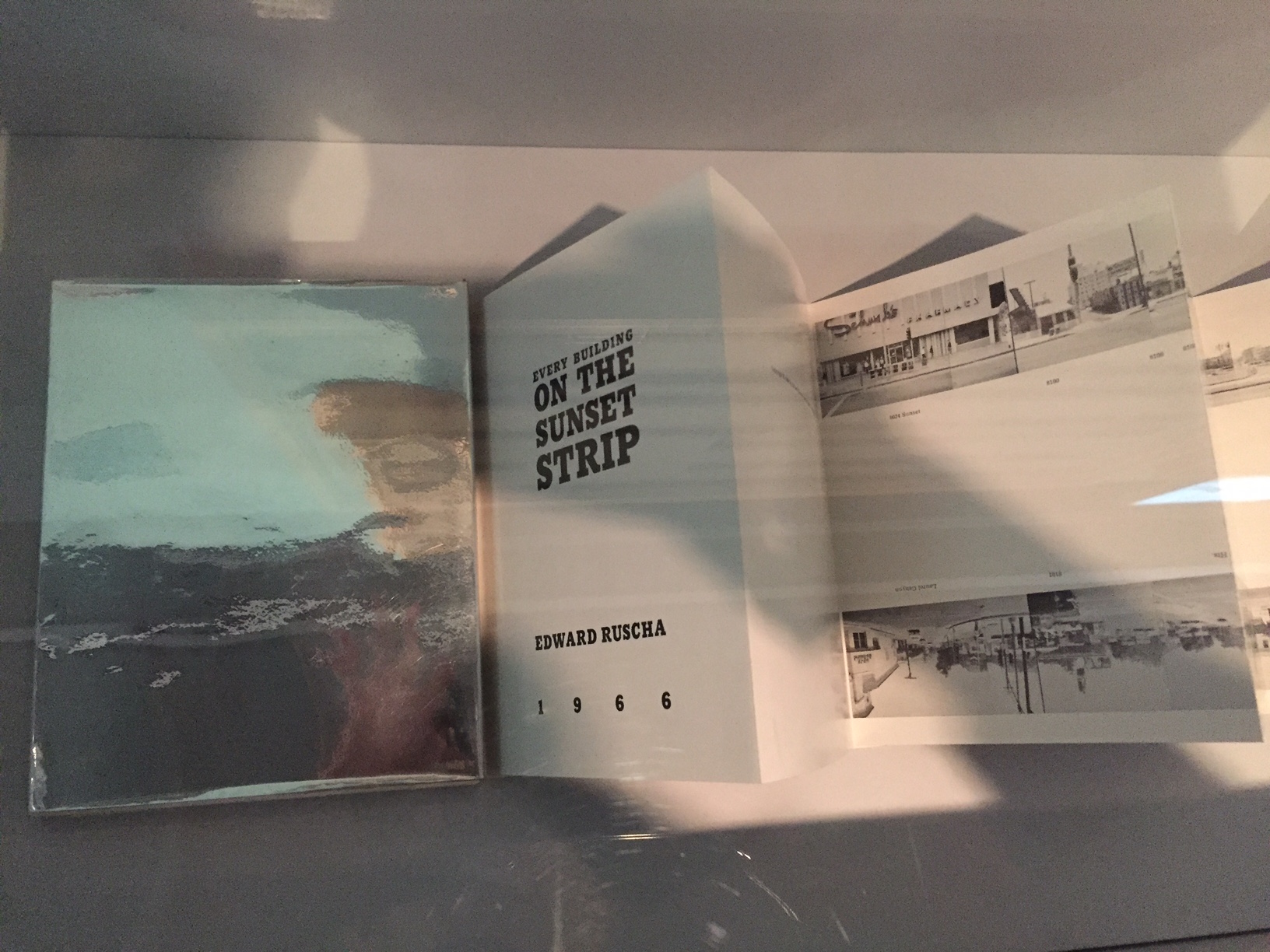

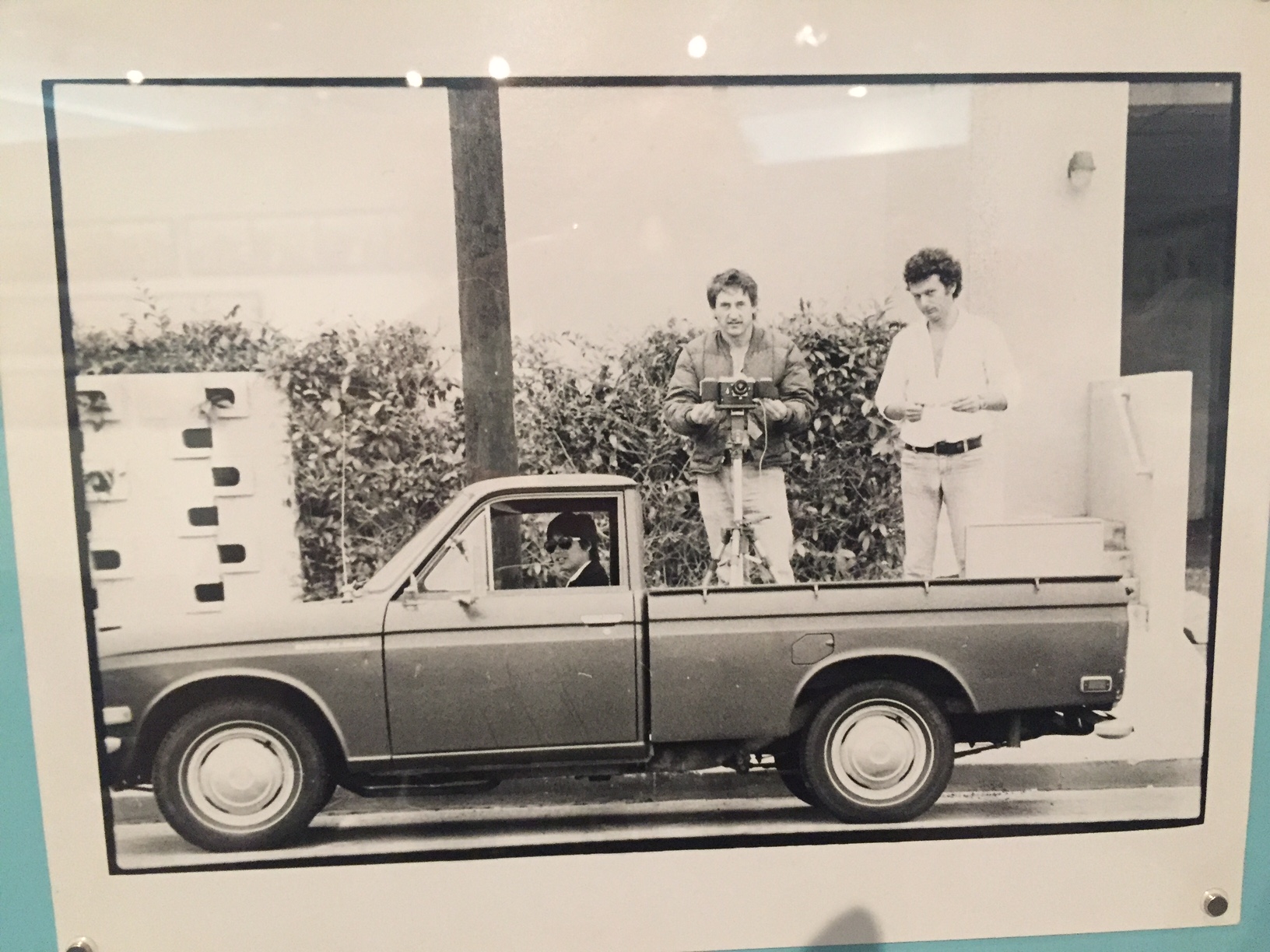

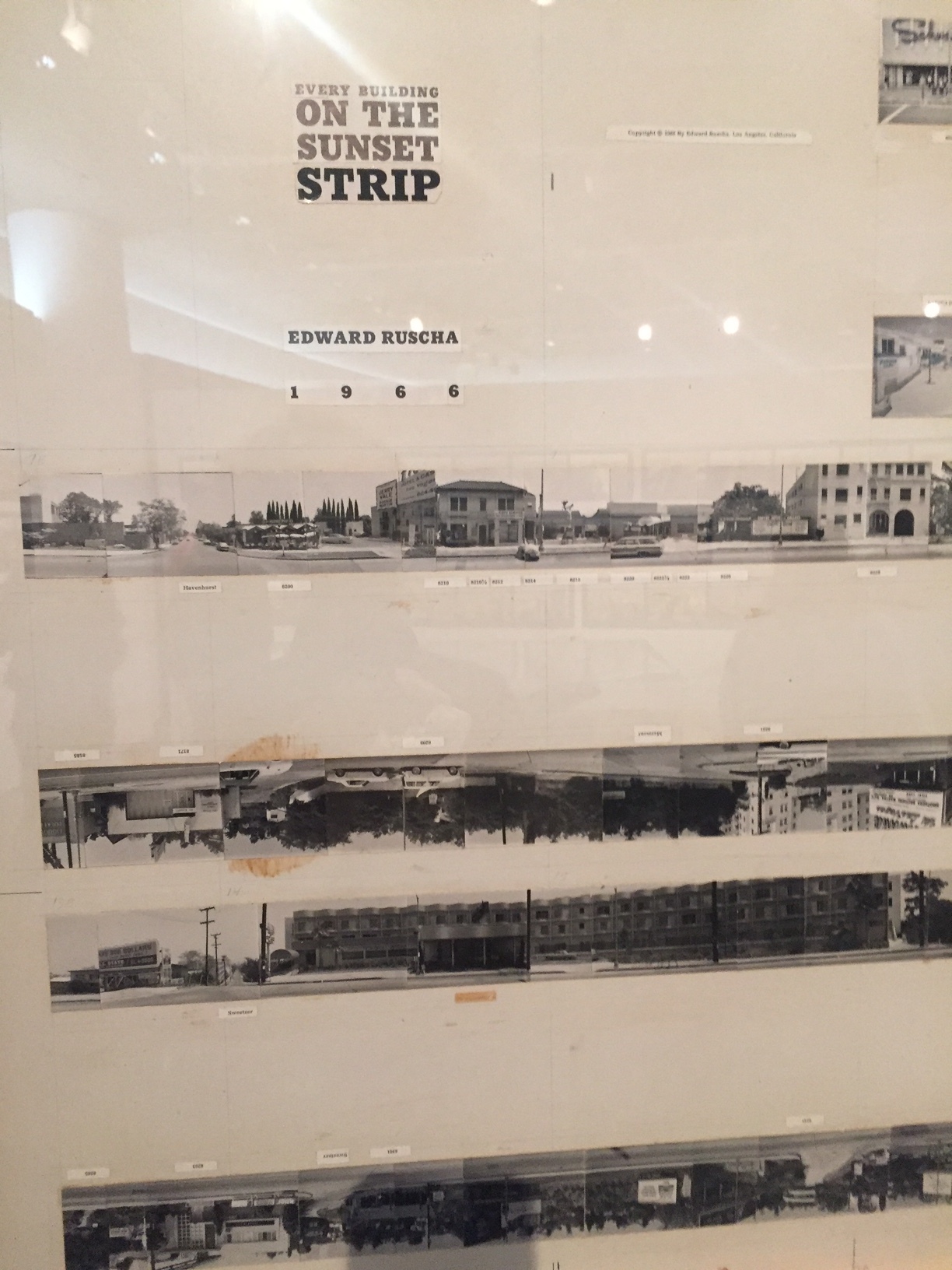

My favorite is, of course, Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip. This small fold-over book, a personal talisman for me loaded with emotional freight, is here backed up by Ruscha’s handwritten production notes for the original shoot (plus a follow up video of Hollywood Boulevard, seen below). This conceptual piece—a pre-animation— has resonance well beyond his original intentions as it serves both as a marker of what once was on the street as well as a new definition of urbanity while more strictly traditional cities were in flagrante of this low-rise kind of density.

In an adjacent gallery, there is some overlap to the MoMA show especially in a charming film of the Yugoslav Tito-era Communist monuments which shows them in overgrown, grassy situ juxtaposed with interviews with locals who live adjacent to them. This verite film is priceless as it captures the solidity of the fantastical monuments as well as their (certainly unintended) whimsy. One commenter dryly notes that “without having moved a muscle” he has lived under 5 successive regimes.

In the museum there is the sublime Renaissance Nudes exhibition, monuments of an entirely other kind. The air is ultra clear and cool and after the fires, it is a splendid time to be in Los Angeles and a needed respite from the more dire news from our nation’s capital.

The importance of Kem Weber, Walt Disney's design guru

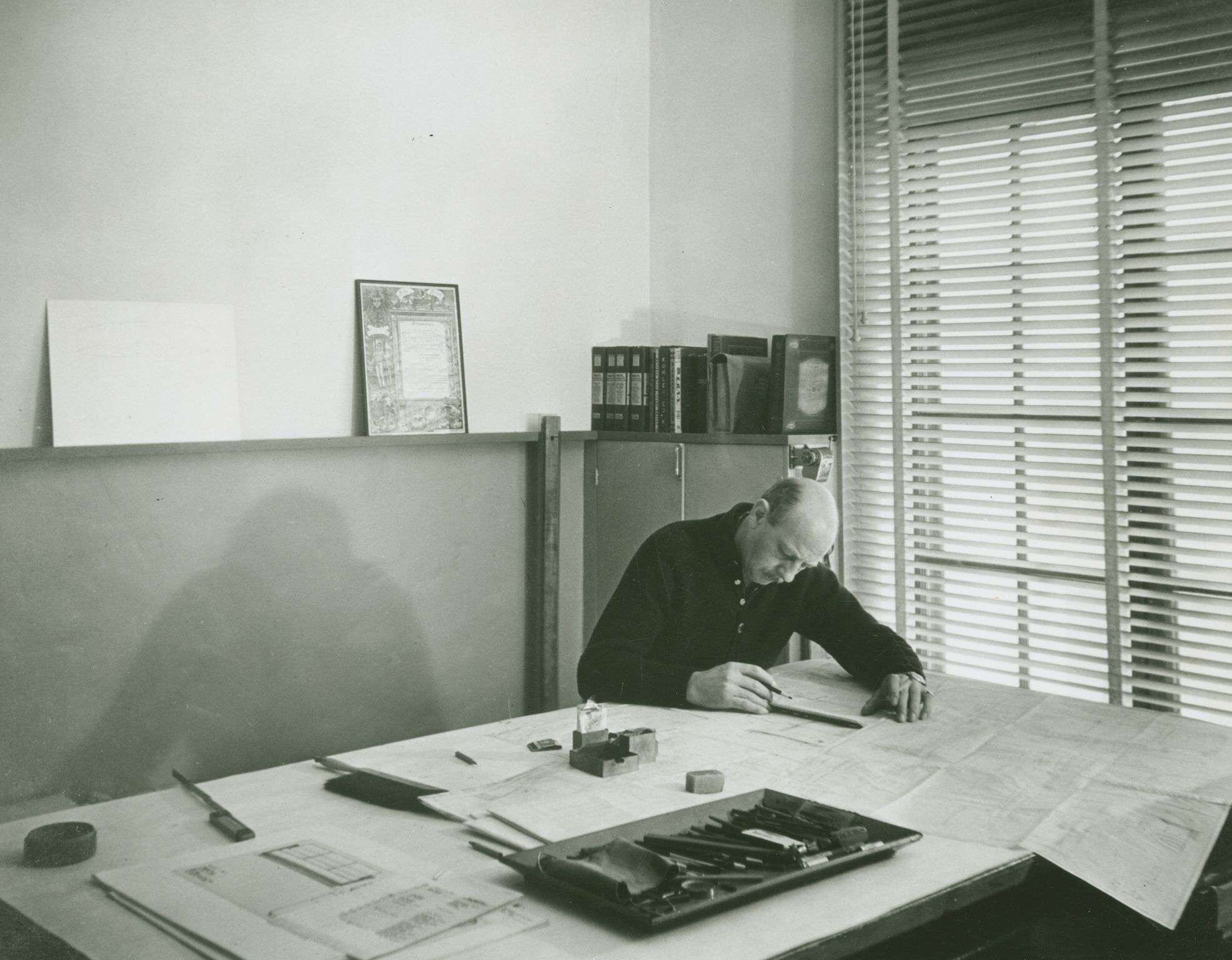

Dave Bossert, a 32 year veteran effects animator of the Walt Disney studio who worked on The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin ,et al, was gifted the original Kem Weber-designed desk that had been his steady support and companion on his departure. His affection for this desk grew into a wonderful new monograph on Weber’s important design contributions to the Walt Disney studios in Burbank.

After the cozy mish mash of the Hyperion studios, Burbank was a streamlined factory. Workers complained that some of the spirit was gone, but in exchange they had the most efficient and beautiful machine from which to make their innovative and highly technical animated films.

Bossert tracked down Weber’s original drawings and renderings for both the exterior physical plant and the custom furnishings at UC Santa Barbara. Each type of artist had a different desk: the flat, expansive kind for directors who had to lay out entire scenes or sequences, the tilt topped, back-lit kind for animators and assistants, the file cabinets, the shelving, the meticulously thought through workstation. Artist input was solicited for the preferred angle of light, the chair style, the comfort, the ease with which they could accomplish the maximum quantity of high-value, technical work.

Bossert was not there during the time period of my Vanity Fair story research on the Ink and Paint department which was the earlier Golden Age, but I know that the workers I interviewed very much appreciated this attention to their comfort and productivity and Bossert says in his era too, they all felt enduring capability and inspiration from their custom-designed surroundings.

Weber was German-born and had worked under a master of the Wiener Werkstatte as well as for the Barker Bros., but there is also much Bauhaus and International style as well as mid century modern in his influences. He found in Walt Disney a true patron who worked with him on almost every aspect of the studio design and who allowed him creativity as well.

Interestingly, Walt admired this kind of industrial design but not the worker collectivity theory behind it for almost as soon as they got to the new studio, the famous Disney strike began for which there was much retribution.

Weber desks have gone at auction for very high prices especially when they were attached to famous animators. I admire Weber’s work, even the smaller occasional pieces, and especially wish the commissary and the coffee shop still existed. Walt’s Weber-designed office is extant in the pink Animation Building, a testament to how innovative his thinking was on every aspect of the dynamic company he created.

Bossert’s beautiful book is for sale here.

Images courtesy of Dave Bossert, copyright UCSB.

Odile Decq: We need architecture to help people live better

Odile Decq had been recommended to me by architects like Thom Mayne as being in the forefront of European architects—male or female—so I was very eager to hear her deliver the Arthur Rosenblatt lecture at the AIA last week.

Decq resembles a Goth Grace Slick. Her look—black teased hair, black clothing, black nails, huge black rings, black eye makeup, and lipstick—is something she may have arrived at long ago to appear strong, to stand out as tough.

Would I need to reference the physical attributes of a man the same way?

If he stood out like this: yes. Absolutely.

This is a presentation as much as anything she says.

I ask her if she has designed her own jewelry and clothing. ‘No,” she answers with a smile, “but why not”. She laughs when she tells us that she wants to design everything in her projects even if she loses money on it. Shades of Frank Lloyd Wright.

This is a woman, a person, for whom creating a whole environment is what she is all about. An atrium with a winding ramp also reminds of Wright. A Barcelona building has Gaudi in it. She invokes the great mid century designer Pierre Paulin in her designs for chairs. She does not ignore history but she is surely the antithesis of classic and conformist.

She loves black. Recently she has also been loving red.

Other than that there is not much else in her palette. Oh, ok, white.

Despite the black, she has a sense of humor, and is charming and funny in delivering an anecdote.

Exteriors are fenestrated. Staircases have glass siding. She wants to be open to the world—and vice versa.

“We need architecture to help people live better,” she says.

Her husband and partner died in a car crash two decades ago—a tragic, defining time for her. Yet, finally after many years of the firm still being referred to by their joint names, in frustration, she took sole title in 2013. Her work is everything to her, She does not take vacations.

She was also frustrated with the institutions where she was teaching so she opened her own architecture school, Confluence, which depends on short term faculty workshops rather than semester long commitments. The enrollment is still small, but she seems undaunted.

Mirrors and shiny surfaces abound in her work. Having just seen the HBO doc which showed Jeff Koons opining on how important his shiny balls and surfaces are to reflect the world I can’t help but be discouraged for a moment.

Then I realize: Decq is not about reflecting the beau monde but rather the real world. It’s an entirely different energy.

I like most of all her restaurant for the Opera Garnier. It’s Courrege-ian, sixties, disco, but also very contemporary. She tells the story of how because of French landmark regulations, she was only allowed to alter the floor. Still, she found a great solution.

I don’t know of any projects of hers in the US but I can’t help but imagine that some ambitious client will soon be unafraid of collaborating with this dynamic woman.

MoMA: Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980

Alongside the fantastical Bodys Isak Kingelez exhibition in an adjacent gallery, MoMA has produced an architecture show Toward a Concrete Utopia of a very different sort, much more in keeping with their comprehensive Latin American show that Barry Bergdoll so deftly curated a few years ago. This is architecture that made a different kind of historical statement, and had everything to do with the post-war Eastern European socialist movements of the 1950s-1980’s.

Yugoslav architecture? It doesn’t sound sexy. But it is! The more I look at Brutalist architecture the more I see the cragginess, the undulation and not the monolithic. And its monuments are apparently a great hit on social media. The images above may tell you why.

The architects will not be household names, but they were deeply influenced by people like Paul Rudolph and Kenzo Tange. This Brutalist ethic was in keeping with the desire for monumentality, permanence and commemoration that swept Eastern Europe at the time. This is a region that has gone back and forth from federation to separate nation-states --these buildings and monuments are the most permanent residue of the shape shifting.

Architecture as a symbol of utopia, dystopia or even myopia—all this is present in the exhibition.

I won’t be able to get to this show right away but I’m very interested in flagging it having plunged deeply into Communist era and mid-century architecture this year in neighboring Prague, Vienna, Berlin and previously in Cuba and Latin America and especially Mexico.

All images courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.