What was it like to get up in the morning as a student at the Bauhaus, first in Weimar, and then in Dessau and finally in Berlin, Germany as political and artistic repression grew? A new exhibition and online exhibit tells the tale at the Getty, complimenting a host of German based exhibitions, open houses, touristic circuits and a new biography of Walter Gropius, its founder. You would certainly feel part of something special. The Bauhaus was not only a technical design school, it taught spirituality and the power of the human-made environment to convey emotion. An artist was merely an exalted craftsman or woman: craft was the heart of any design enterprise.

You might throw on your loose fitting dress or pants and take a walk before breakfast-outdoor exercise was encouraged. Your hair was long and free if you were female, or you might have shaved it all off if you were male. You might see the great Gropius himself or the mystic painter Johannes Itten with his shaved head and long robes. You might take class with Kandinsky or Klee. Though you were part of an almost 50% cohort, if you were a female student, you were likely headed eventually to specialize at the weaving workshop under the tutelage of Anni Albers--where most females were relegated despite their many requests to be further integrated into the programming. “Student Lotte Gerson had assembled a design project about balance from the glass neck of a lamp through which she suspended a spiral cut from a cellophane bag. According to her note, the bag had held clippings from haircuts in the women’s bathroom, a “radical break with bourgeois traditions!” the Getty curators note.

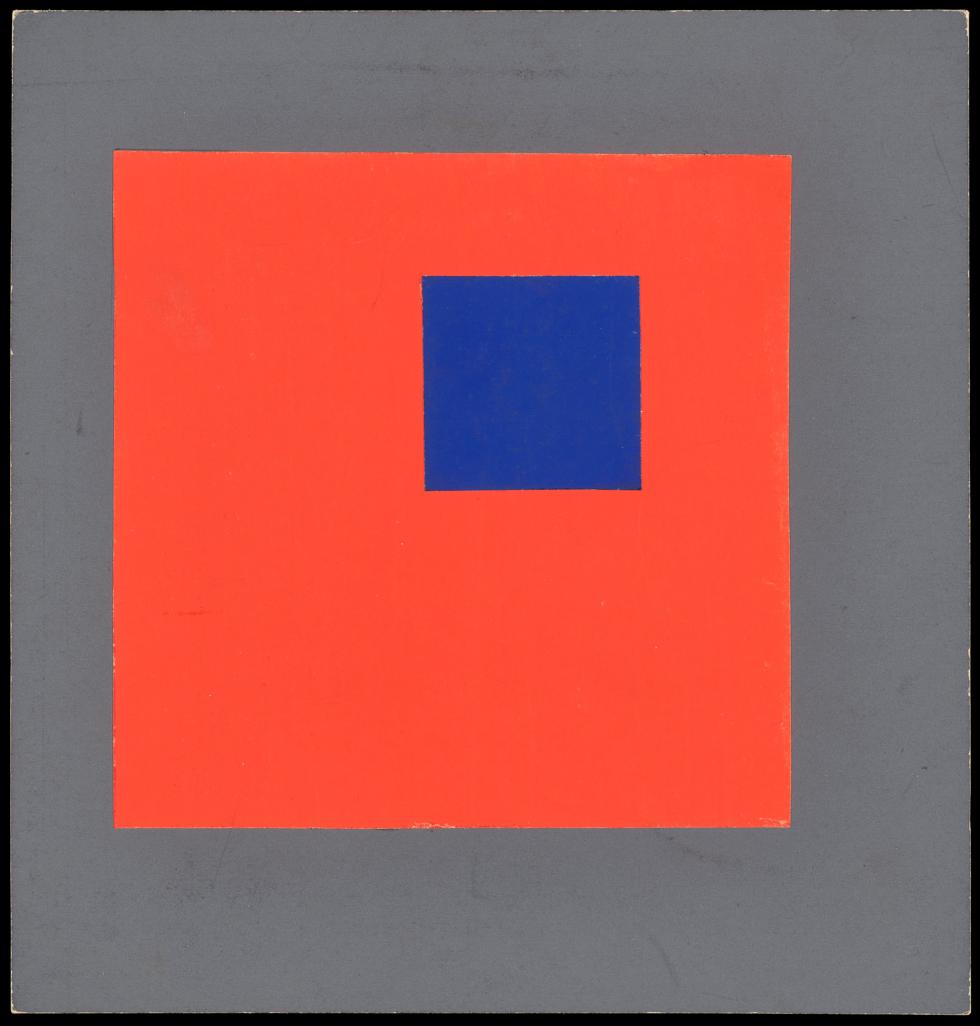

You might get to participate in the building of Sommerfeld House, which united all the disciplines in a gesamkunstwerk even if you yourself were not yet fully formed integrated individual and later on the Haus Am Horn, a more industrial space which became famous. Architecture was considered a fully holistic enterprise in those years, against the notion of starchitecture. Why architects were just another kind of craftsman. You would have been studying color and form, squares, circles, spirals, and taken a life drawing class. You were to become familiar with many different materials (wood possibly being held at the highest level for its integrity and natural properties) and you would have come to understand the importance of light. You might have made woodcuts and then prints.

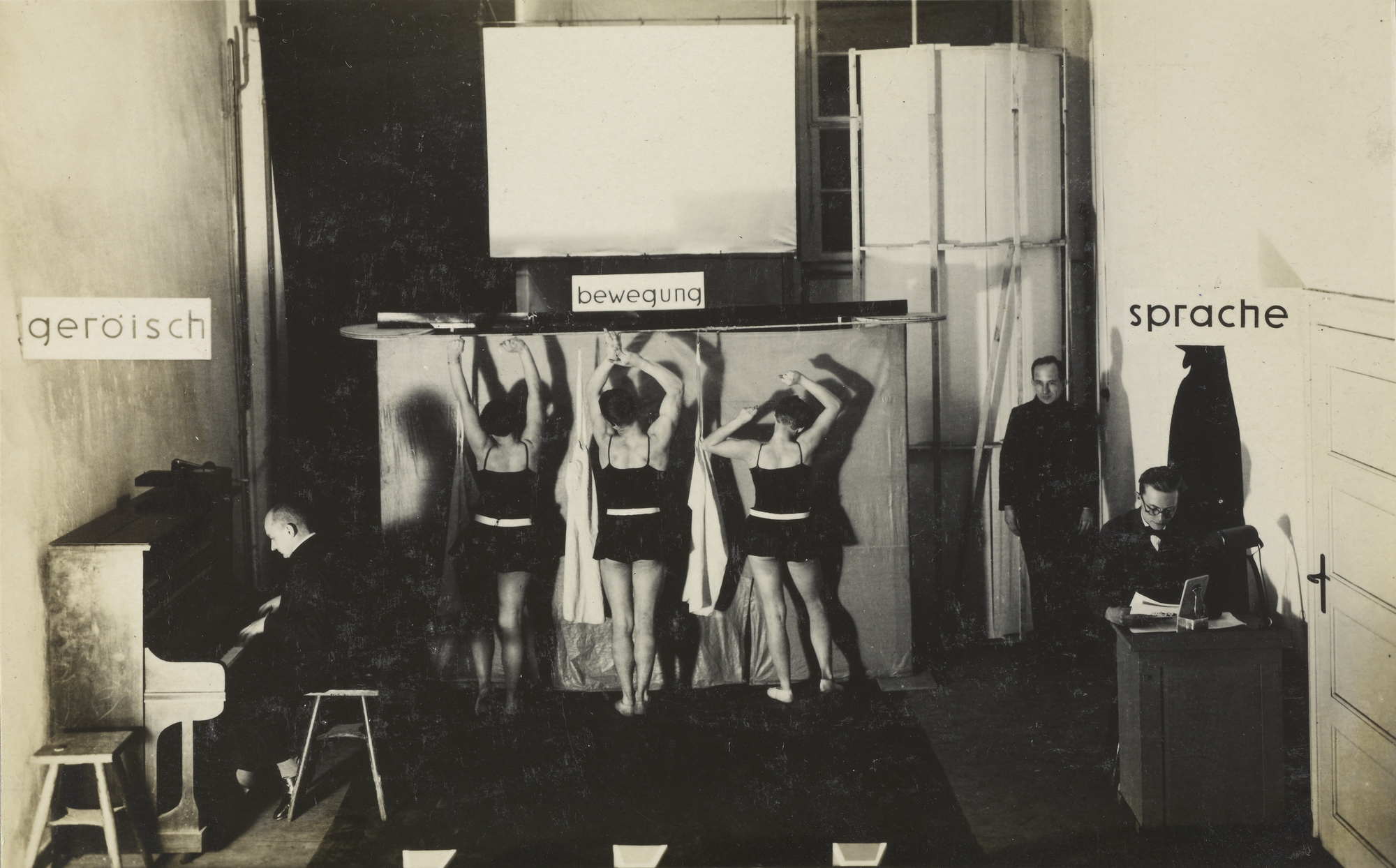

It was not all work. There was joy, revelry and hopefulness at the outset. There were performances and music and parties galore. You would likely have fallen in lust or love with one of your classmates or had a crush on one of your famous, dynamic professors. But the school faced pressure from other manufacturers who feared competition for their products as well as politicians who decried its supposed Marxist leanings. Gradually the hopeful spirit was eradicated and the school closed in 1933, a victim of fundraising shortfalls and of the bourgeoning German authoritarianism.

To learn more about the Bauhaus and its history and importance, be sure to check out the very comprehensive online exhibit that accompanies the Getty exhibition. In particular be sure to create your version of Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet (ingenious)! which is the coda to the online site. Also consider reading the excellent new biography of Walter Gropius by Fiona MacCarthy. You might also be interested in my story on Grete Stern, the photographer who had studied at the Bauhaus from the time of the MoMA exhibition in 2015.

Photo Credits:

Léna Bergner (German, 1906–1981) Durchdringung (Penetration) for Paul Klee's Course, ca. 1925–1932. Watercolor and graphite on paper Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (850514) ©Heike Sobotta, Sylvia Greiner, Hannes Bergner, Pierre Meyer, and Anna Aniceto

Erich Mrozek (German, 1910–1993) Study for Vassily Kandinsky's Farbenlehre (Color theory) Course, ca. 1929–1930 Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (850514) © Estate Erich Mrozek

Léna Bergner (German, 1906–1981) Carpet Design, ca. 1925–1932 Gouache and graphite on paper Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (850514) © Heirs of Léna Bergner. ©Heike Sobotta, Sylvia Greiner, Hannes Bergner, Pierre Meyer, and Anna Aniceto

Irene Bayer-Hecht (American, 1898 - 1991) [Theatrical Sketch "Geroisch - Bewegung - Sprache"], about 1923. Copyright status undetermined, Credit: The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles