I have to 'fess right off the top that I have not traditionally been a Giacometti girl. The attenuated, anorexic figures so well known and well distributed to many museums and collections around the world have always disturbed me despite their elegance. (One of the best installations is at the Louisiana Museum in Denmark.) Here’s a case where “you can never be too rich (to own one,they are very price-y) or too thin (in form)” does not actually hold up.

Nevertheless, the Guggenheim has mounted an appropriately gracious show in conjunction with the Giacometti Foundation, Paris: spare, quiet and in some ways, revelatory.

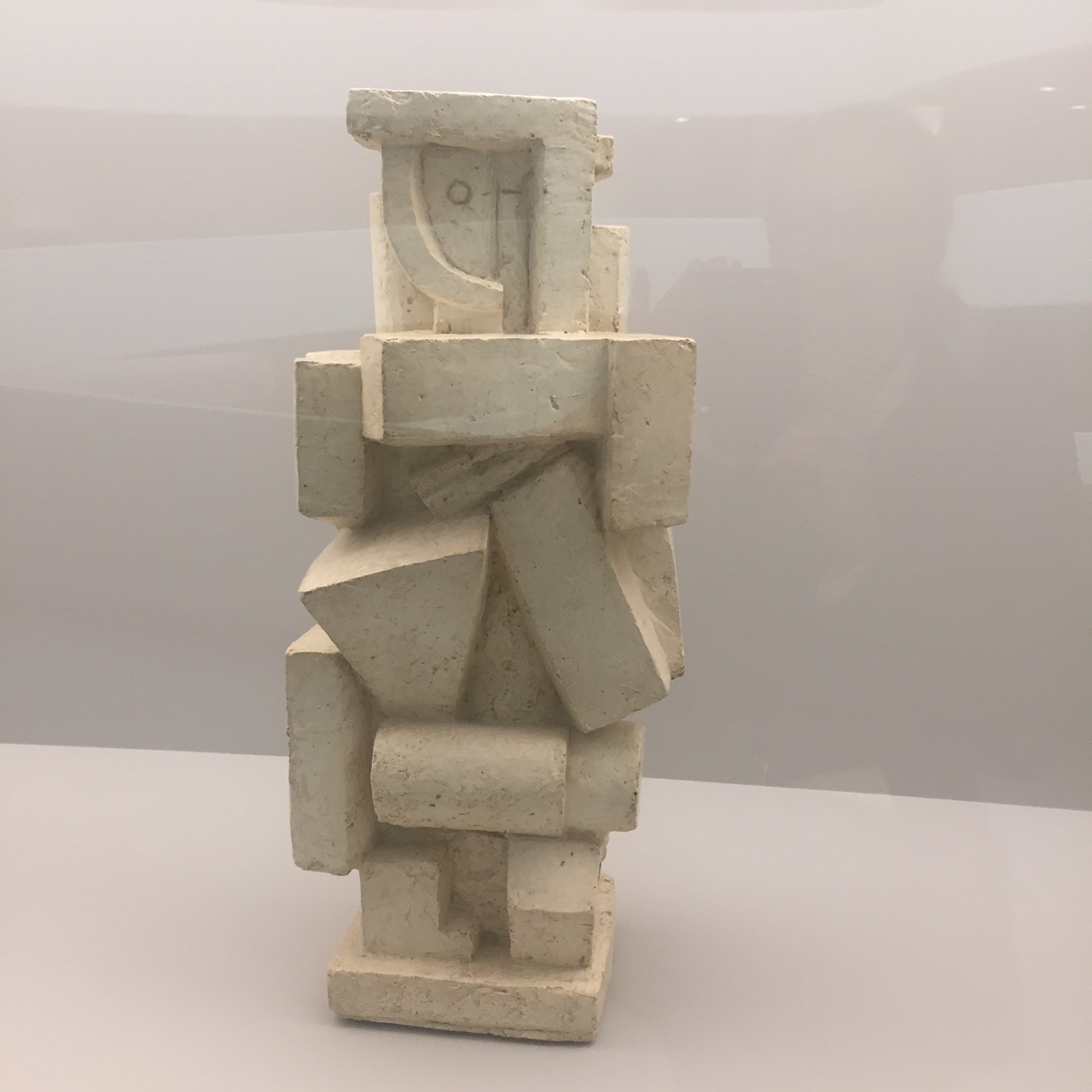

The great thing about this show is a chance to see the early work with which we are less familiar. The white sculptures for example have a solidity that the black ones don’t. Somehow Giacometti approached these with a different eye.

The bronzes are the stars. Though MoMA owns two of the best, I don’t recall communing with them there, they are haunted by Giacometti’s visits to the Trocadero ethnographic museum. In particular the Femme Egorgee (Woman with her Throat Cut) from 1932, a Louise Bourgeois-ian surreal work he made for Peggy Guggenheim, is beautiful and leapt out at me as a perfect symbol for the #MeToo movement.

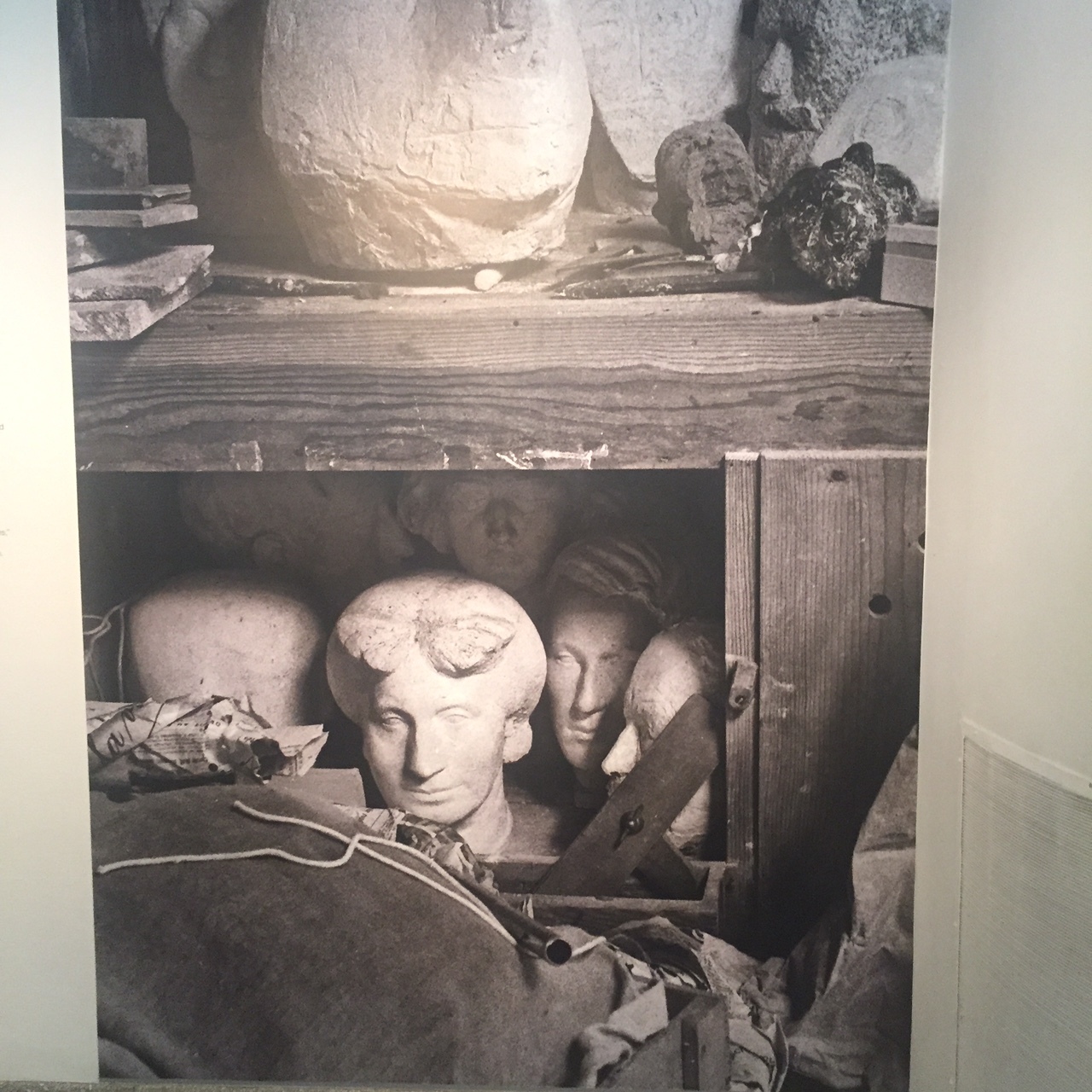

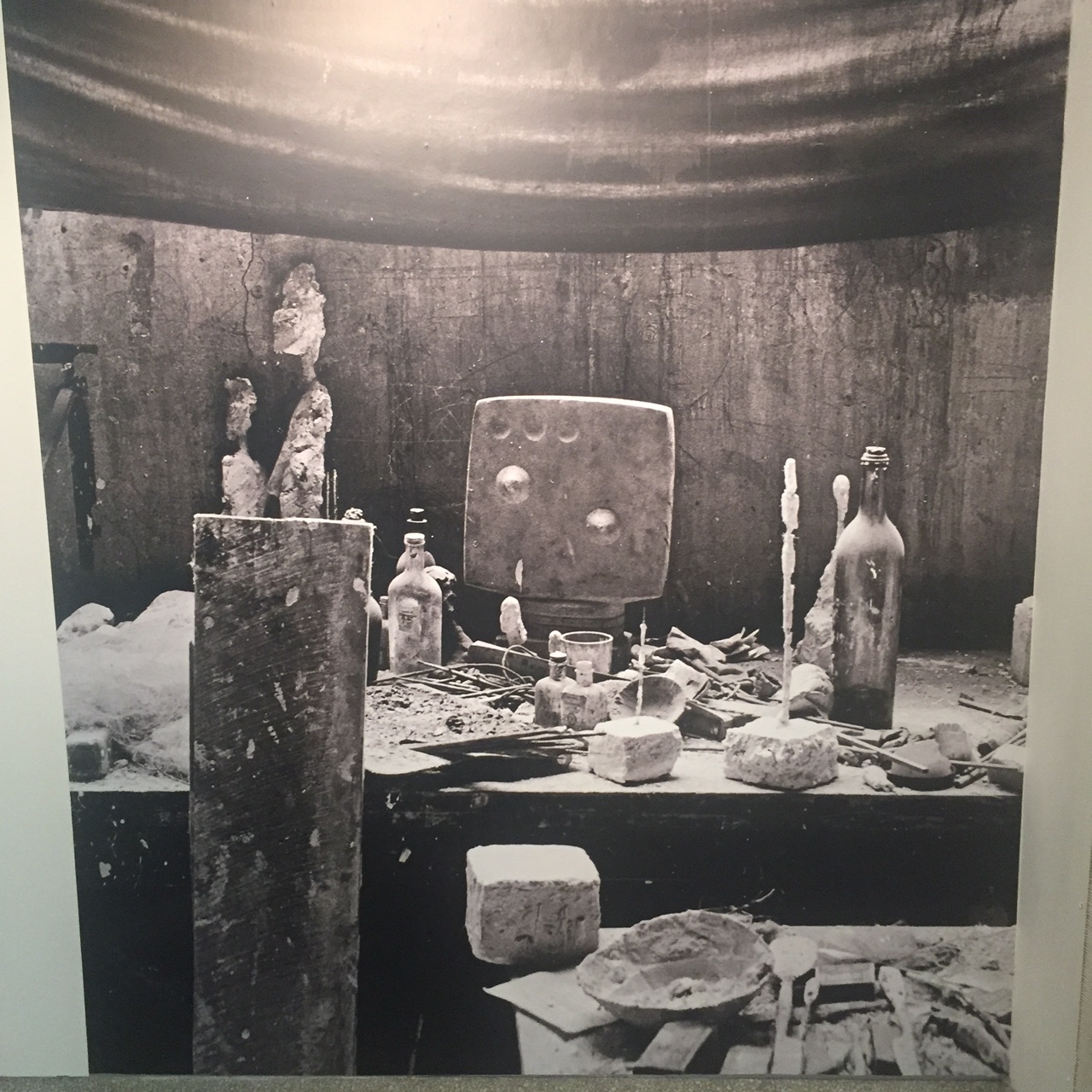

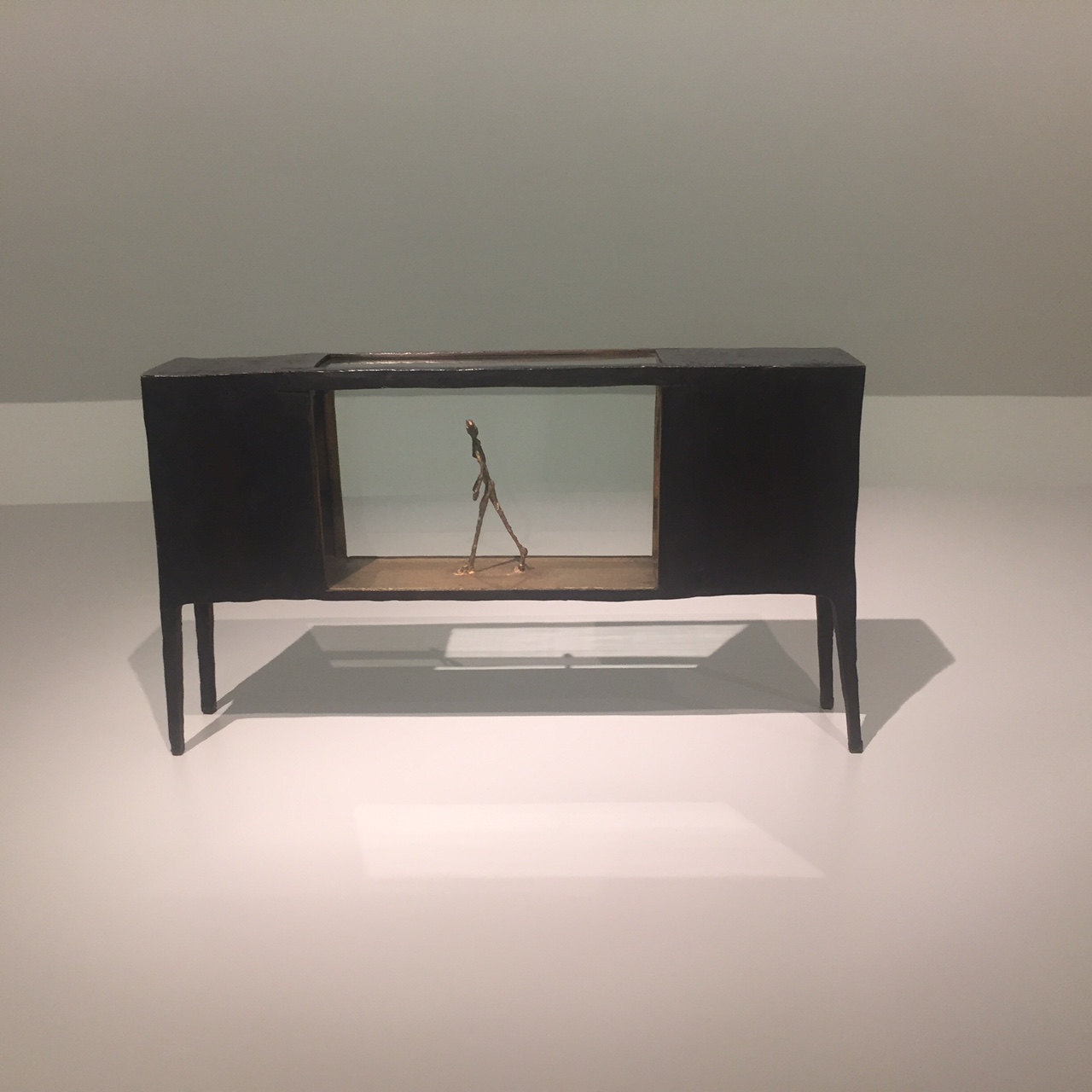

Born in Switzerland of a distinguished artist father, he soon moved to a studio in Montparnasse where he worked most of his life. He studied with Bourdelle (whose studio is now one of my favorite Paris museums if you haven’t been) but was soon influenced by Brancusi, Laurens, Picasso and Lipchitz. He worked largely from live models, his brother and his wife. When he was not permitted to re enter France during the war, he began the “smalls” that are diminutive versions of his “talls” but have an outsize impact. (I’m told his studio will be open to the public next year) He grew preoccupied with existentialism and death, and these motifs come across in most of the late work.

A documentary film at the top of the ramp is worth seeing for the uncanny resemblance of Giacometti to his work: his sunken cheeks, long neck, pointed chin, protruding lips, his wiry, grey hair all speak to an auto-portraiture that made me fonder of the drawings. “When you look at a man, you look at his eyes,’ he said, “the expression of the eyes is the most important thing in the face.” Giacometti had very soulful eyes.

‘I think I know what I’m doing and then when I start working everything is lost,” he explained to an interviewer. I know just how he felt.