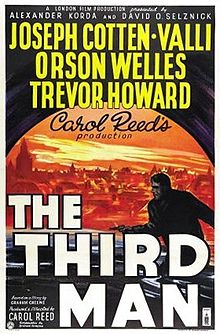

Just as I used Kundera in Prague as a warm up, I used Graham Greene to prepare for Vienna. The Third Man was written for the screen, but in between, in order to get his story down, Greene wrote a novella which laid out the post war Vienna thriller he had been commissioned by Alex Korda. We all love the film, but in fact this thin volume has some significant differences—and pleasures-- from the eventual film which Carol Reed, the director, shaped to his vision.

The exterior of Vienna and some select buildings in the interior Ring had been destroyed during the war but more importantly the city had been carved up into four sectors delineating the different holdings of the Russians, Americans, British and French. Greene took this divisiveness and ran with it, setting Rollo Martins (who became Holly in the film) and his quest to discover the truth about his slippery old friend Harry Lime in the watery, dark, sewery, wintery and chilly city. The Vienna I experienced though cold was slightly sunnier. In actual fact, I learned from Kerstin Timmerman whose family has the lock on the most engaging Third Man Tours that it was fall when they shot and Reed had them slick the cobbles down whenever necessary. Timmerman’s tours include lots of marvelous tidbits about the production of the film as well as a zither performance of the famous theme music—not to be missed.

Vienna felt like an overly-opulent bubble bath after the austere beauty of Prague at first glance. But I came to appreciate its more hidden spaces, once again through the meticulous offices of Insight Cities local expert guide, Felicitas Konecny, who is also part of her own network of architectural tours.

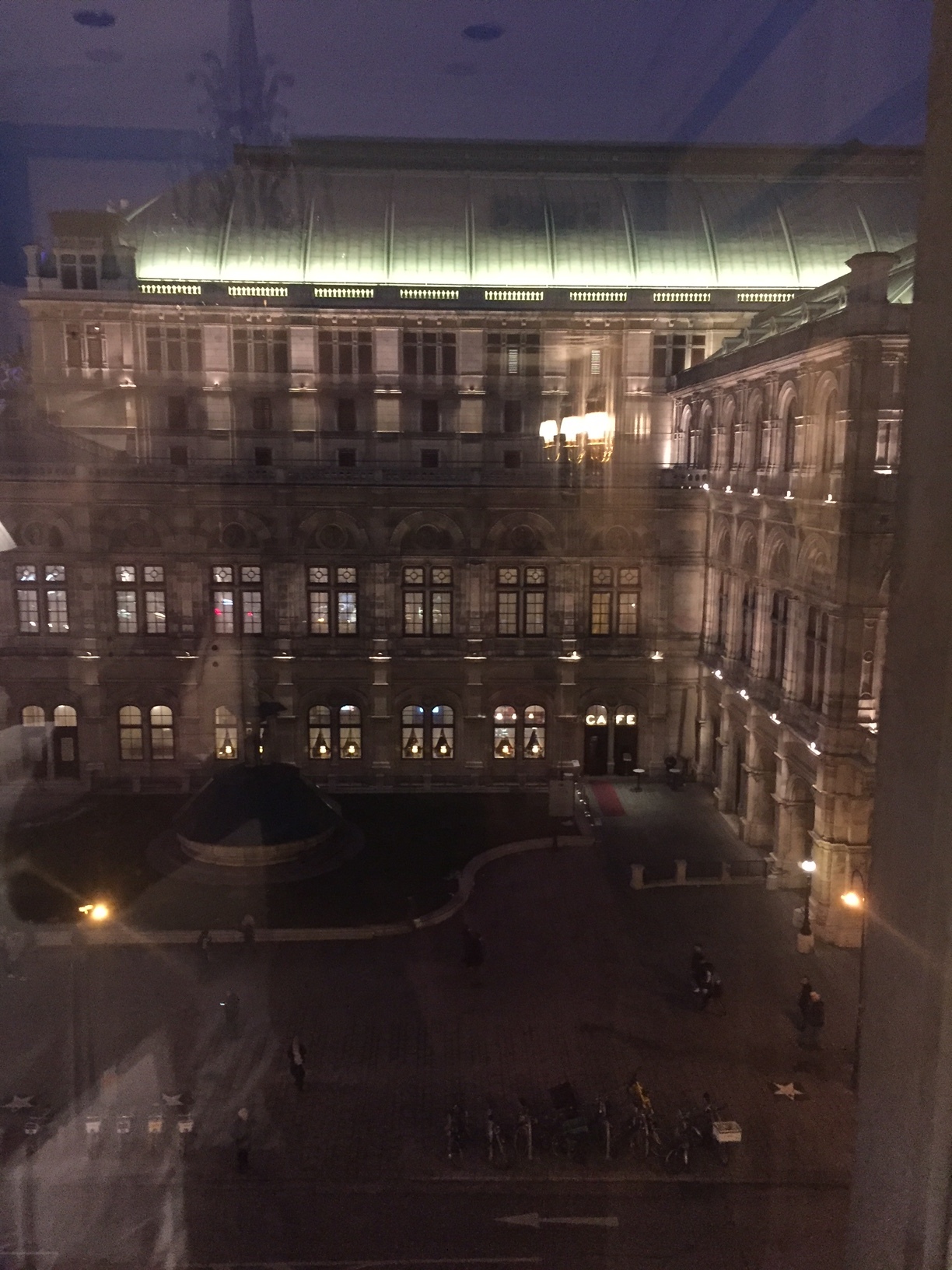

Felicitas was brilliantly prepared for our half day express tour of Vienna, and had done considerable homework for my visit, tailoring her tour to things she thought I might enjoy. She was flexible and thorough, and was able to get entry into places most people can’t. Again, I was looking for modernist Vienna, the Vienna beyond the grand Opera House which I was able to see right from my window from the vintage Hotel Bristol, itself a pastiche of high Habsburg-ian curlicues and brass fittings, with a devoted Austrian clientele who had come for the most important ball of the season, the Opera Ball and stayed for others.

Thus again I was well situated in the center, within walking distance or short U-bahn distance of almost everything we saw that first day. Felicitas was diligent in telling me about Viennese architectural history but I really began to perk up when we got to the Looshaus, originally a men’s clothing store and now a bank, having just been in his Villa Muller. The Hochhaus Herrengasse consisting of shops, offices and apartments still has modernist charm inside despite the rather garish shops on the ground floor as does the modernist Wittgenstein house for his sister Margaret which is something of a rundown letdown on the inside now owned by the Bulgarian government which at least has saved it from the wrecking ball. The soaring Otto Wagner designed former post office, now sadly abandoned by the bank which had taken it over and whose fate is still undecided is luckily still in pristine shape. After a necessary break at the Provencale style Paremi bakery we visited my favorite site, the Josef Plecnik 1905 narrow mixed use building for Johann Zacherl an industrialist. Again, we immediately needed chocolate and stopped at Leschanz for a dark chocolate brick for me and a malted milk ball for Felicitas. Vienna is like that: you must take the sweet at every opportunity. Another Loos interior, the Knize men’s clothing store, with its original green linoleum flooring, polished wood walls, and vintage dressing rooms is also a treat. We finished with the Third Man tour and slipped into see Klimt’s Kiss at the Upper Belvedere Museum and then I happily collapsed at a charming restaurant Felicitas found, Zur Herknerin, completely authentic cooking as if mother had made it (generally mother does make it.)

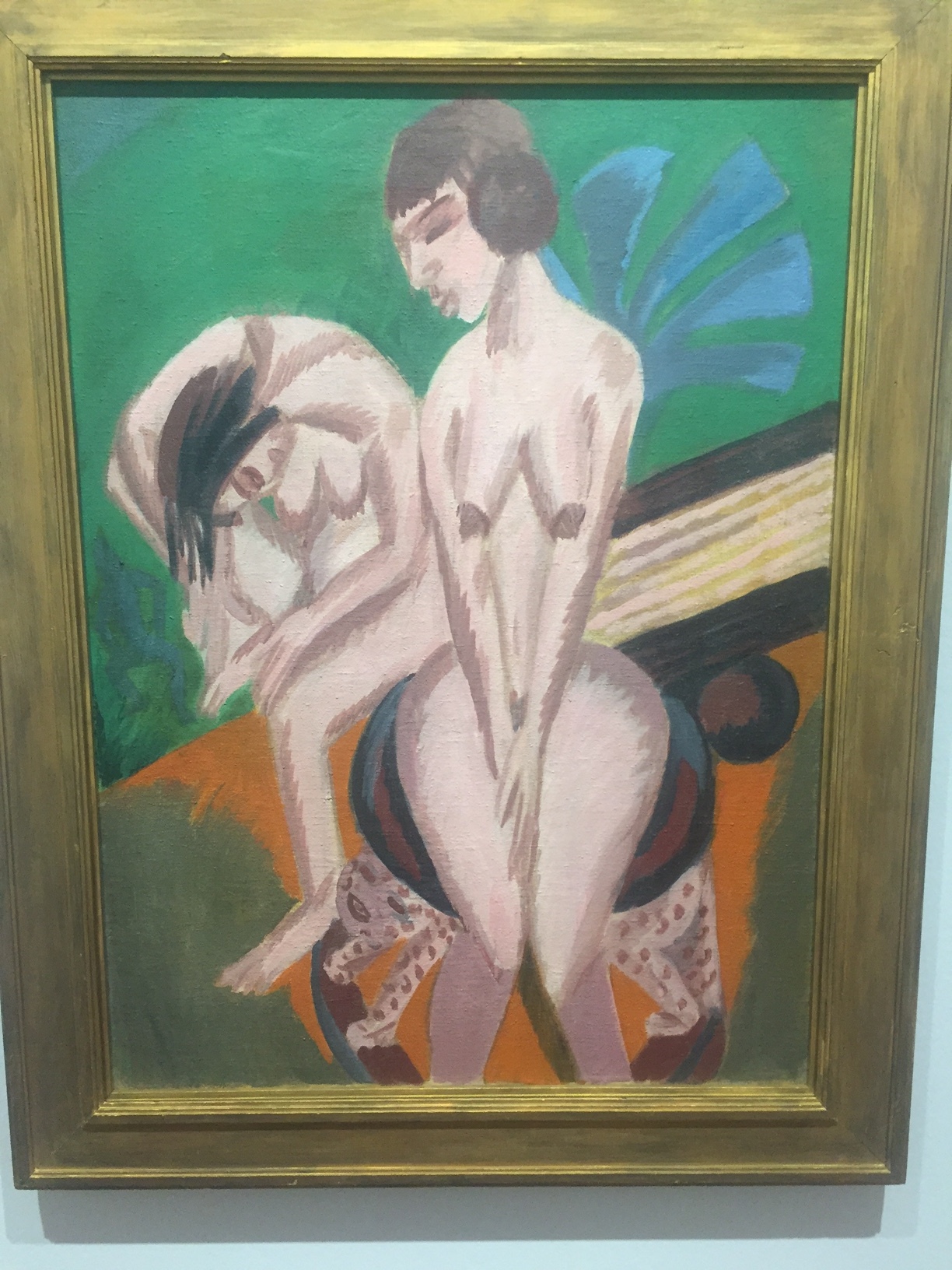

The following two days I had to devote to Vienna’s overwhelmingly excellent museums. While they were building the over-the-top palaces, the Habsburgs were also voluminous—and largely discriminating-- collectors of art and they passed this tradition down to other Viennese. I was in museum heaven in Vienna, first at the Albertina, which has among other lovely things, a very good encyclopedic modern painting collection and a wonderful survey of architectural drawings and then at the famous Kunsthistoriches (soon to be parsed by Wes Anderson). Like the Metropolitan or the Prado, this can be exhausting but the museum has couches everywhere understanding that this plethora of A plus art can be overwhelming.

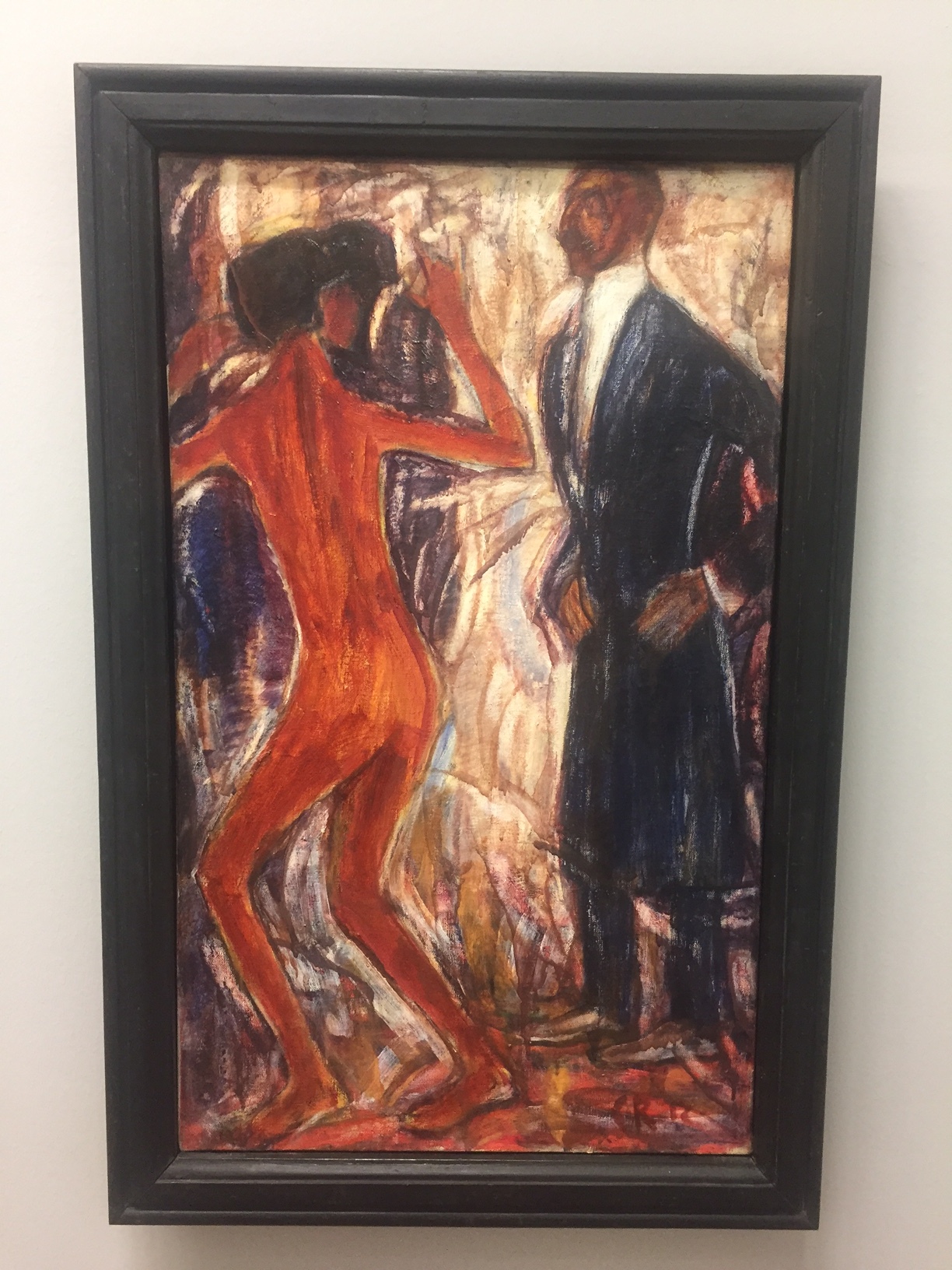

Then I shifted gears (and centuries) at the Leopold Museum on the adjacent square across the street. I was unprepared for the fascinating historic time line and breadth of work of Egon Schiele, the attractive, louche, rebellious, bipolar disciple of Klimt’s whose work in this context was more important than I had ever seen it. (The Leopold also has a terrific cafeteria of Asian specialities)I then bisected the city through the many palaces as I ran to my appointment at the Kunstforum Wien Bank Gallery (a separate post follows on the excellent Man Ray show there).

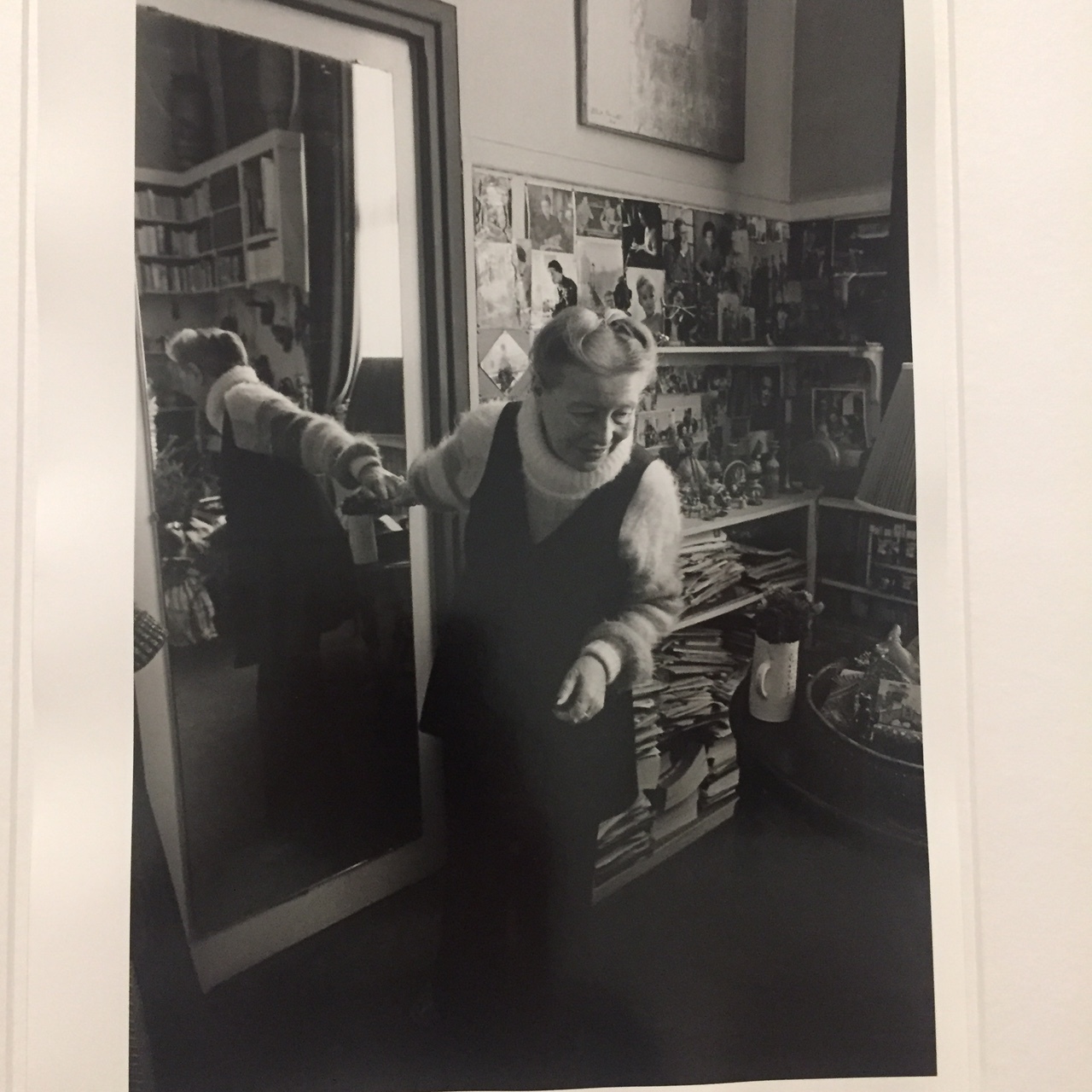

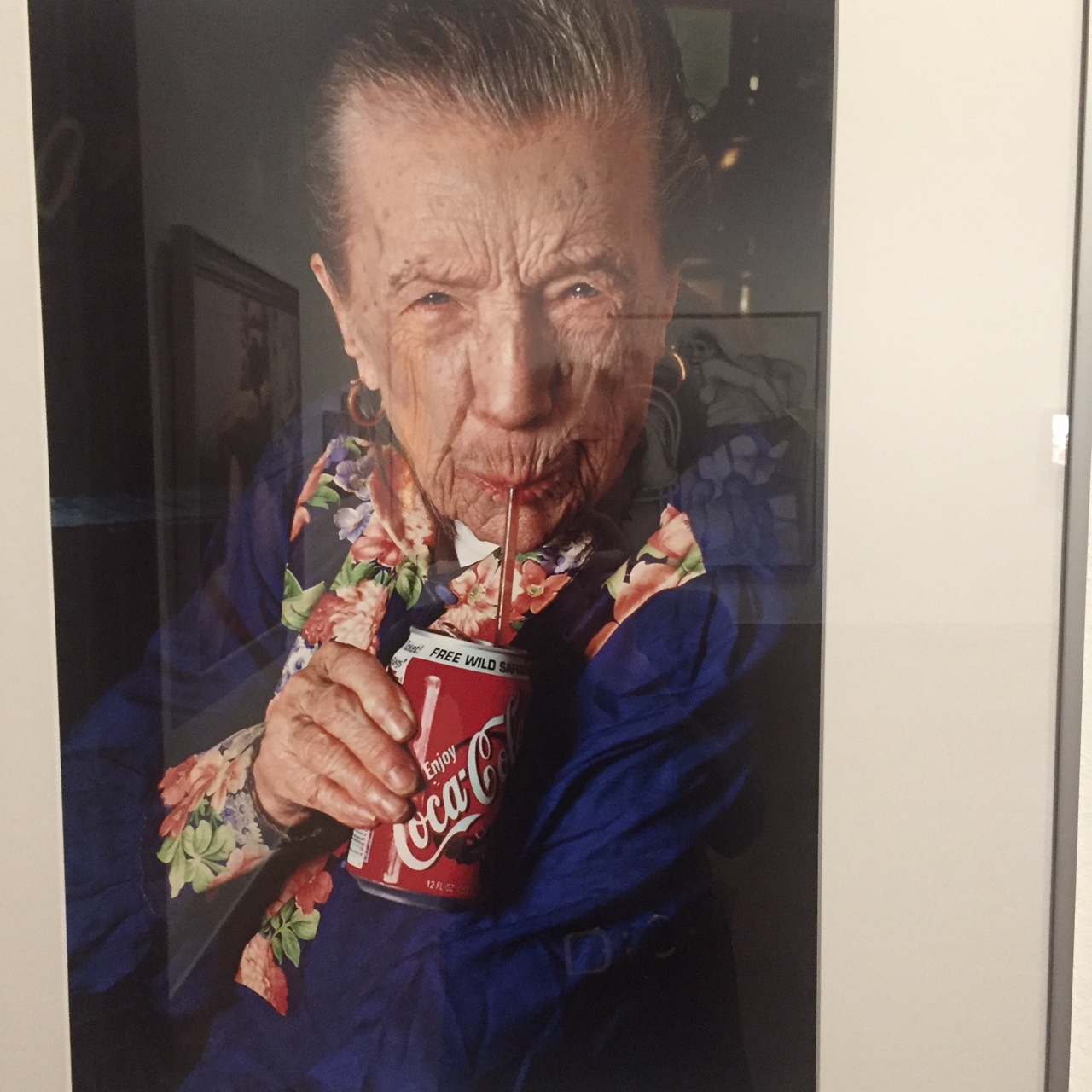

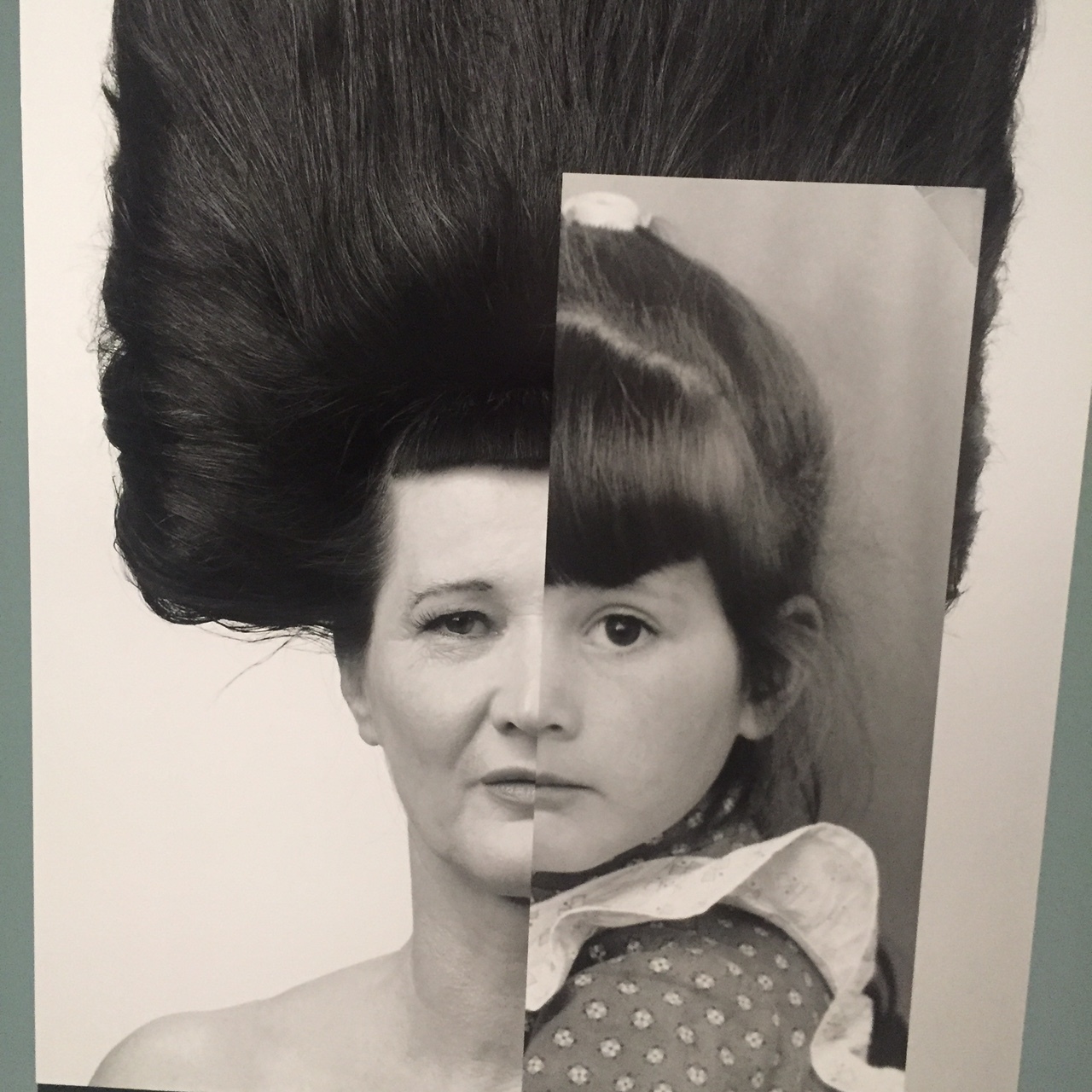

That night, I of course had to take a ticket to Elisir D’Amore at the opera, a fusty production but with an excellent young cast. Again: absolutely packed with young aficionados. I was up bright and early to take in the show Jason Farago had conveniently alerted me to just that morning at the Lower Belvedere on Aging (something preoccupying me of late, see Louise Bourgeois and Simone de Beauvoir, two heroines of mine, below) and then the adjacent slender but lovely show on Zagreb Modernism at the Orangerie. Then I climbed to the Belvedere 21 Museum , another building repurposed from the Brussels 58 fair, which has a riveting if challenging show on the performative artist Gunter Brus who makes Marina Abramovich look positively tame.

On the door to my room at the Bristol was a name that had intrigued me, Heinrich Karl Strohm and a date 1940-41. It turns out that the Bristol had dedicated each of its opera-facing rooms to a director of the Opera through the decades. I had resolutely avoided thinking about the Austrians during the war, and barely discussed this with Felicitas, but this made it virtually impossible to ignore..

When I got home, I did a little homework. In 1938, Anschulss had already occurred, fulfilling Hitler’s dream to annex Austria. Shortly after, Kristallnacht destroyed almost all the synagogues and by 1940, the Jews were thoroughly driven from their homes, jobs and businesses. 6000 Jews had been deported to Dachau and the ones who remained like Jewish actresses were cleaning the theater--and likely also the Opera-- toilets (by the way, the Opera bathrooms are now a fifties delight, it must be said). By the end of 1941, 130,000 Jews had left Vienna. This then was the exact period when Strohm had overseen the Opera. Had he actually stayed in my room? I don’t know.

Like the US, and Germany, and Poland and Holland, and Israel, Austria is listing to the right again and many Americans I spoke with said they would not travel to Austria.

I feel this is wrongheaded. After all, we live in a place where a racist, maniacal despot has taken control and we need make many apologies ourselves for allowing this state of affairs to occur. I thought the Austrians were welcoming and warm (in fact warmer than the Czechs) and though they are still proudly sporting fur coats in the streets, there is a love of art and culture and music which binds us together. The more we interact, the less of a chance of the events of 1940-41 will likely re-occur. We must remember but we must move on.