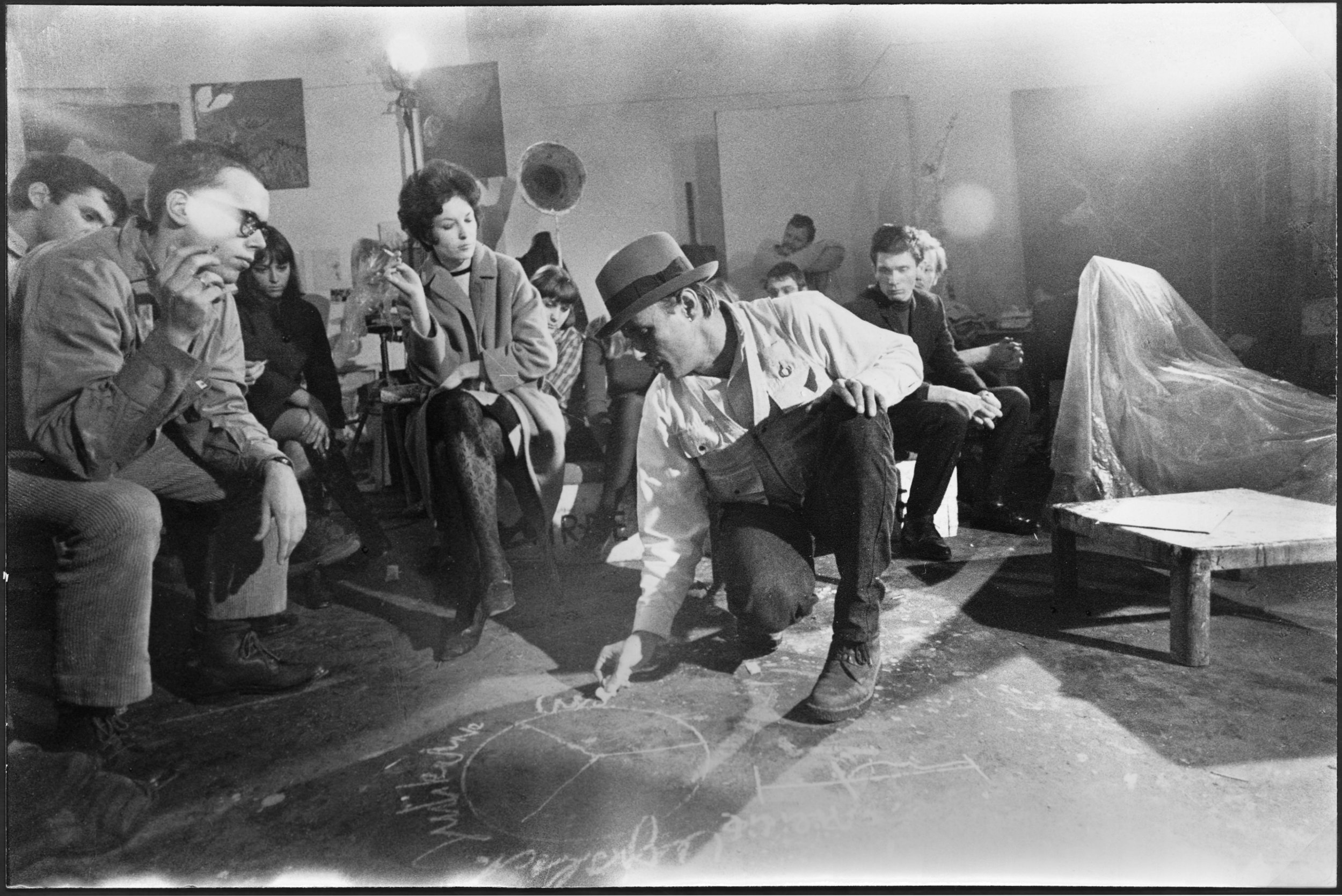

“Some people can walk into a room and see inside people,” says Joseph Beuys in a flak jacket (or is it a fishing vest?), white shirt and dark pants at the opening of a new film by Andres Veiel. Beuys then mounts a ladder. He takes some kind of gelatinous material off the wall and shakes it onto a tray. A crowd of 1971 square black eyeglasses and dangle earrings surges around him. It’s scary. What will they do with or to this renegade?

Josephy Beuys was many things: artist, filmmaker, provacteur, socio-political agitator, activist, professor. He wore many hats, but his one hat, his fedora which both made him stand out and hid him, also covered up his extensive war wounds (he had been shot down as a rear gunner for the Luftwaffe after having been in the Hitler Youth). As Warhol had his blonde wig and Haring his dreds and Wegman his dogs, Beuys had his signature hat and his complicated and sad family history informed his work which was both monumental and delicate.

He was catnip to journalists. At the Guggenheim, Beuys is having his first US retrospective in 1979. They are trying to get close, to explain him. Viewers are trying to understand. The yards of gray felt nestled like a beehive, over a piano, a chair with a resin slope illustrates his anti-theory that art can be anything, made by anyone. As a social philosopher, a public debater about the role of art, the artist and and politics, he had few competitors. At a symposium, he is dripping sweat, feisty and contrarian in front of an elite audience. As the others try to maintain calm, he is voluble and passionate. He wants to provoke people. Expand their consciouness. Forget theory.

"Whenever people ask me if I’m an artist I say.' Oh cut the crap.'”

He participates in Documenta—puts it on the map- in a time when art biennials and fairs were sparse. He foments a revolution at the Dusseldorf Academy of Art where he teaches. He comes to New York to spend three days with a coyote in a gallery—one shaman to another-- and returns to Germany without setting foot in the rest of the city. The natural world held out its mysteries to him as well, evidenced also in a tree planting project he pursed for many years.

Beuys’s life and work was much documented. The animated contact sheets we see are a good substitute for video as they break down his process. And I appreciated no narration for a change, and very few talking heads. Beuys and his images tell his own story.

Alas, his sharp mind and a penetrating gaze was beset by chronic depression and despair. After the war he grew emaciated and stopped work. Gradually he came back to life, but had periods throughout his life that were crippling. His phoenix moments came in tribal rituals in fat and felt.

Beuys felt art is a joint task: viewer and artist are complicit. The artist must reach inside the viewer and activate him. This film succeeds very well in that regard.