The Louise Bourgeois show at MoMA unfolds like the paper flowers you used to drop in water.

Eschewing the merely chronological, Deborah Wye, MoMA’s (now ex) longtime Bourgeois expert, instead takes a thematic approach which allows for the graphic work—this exhibition’s focus-- to bump up against sculpture, textiles, other artists who influenced her, and in a revelatory way, her personal demons.

Those who have previously followed Bourgeois’s trajectory from mistress of a tiny art book corner of her father’s bookstore in France to wife of important art historian to ardent, diffident, insecure Art Students League student, to colleague of expat Surrealists to important NY art personage with a weekly salon and many acolytes will recognize some of the works on display.

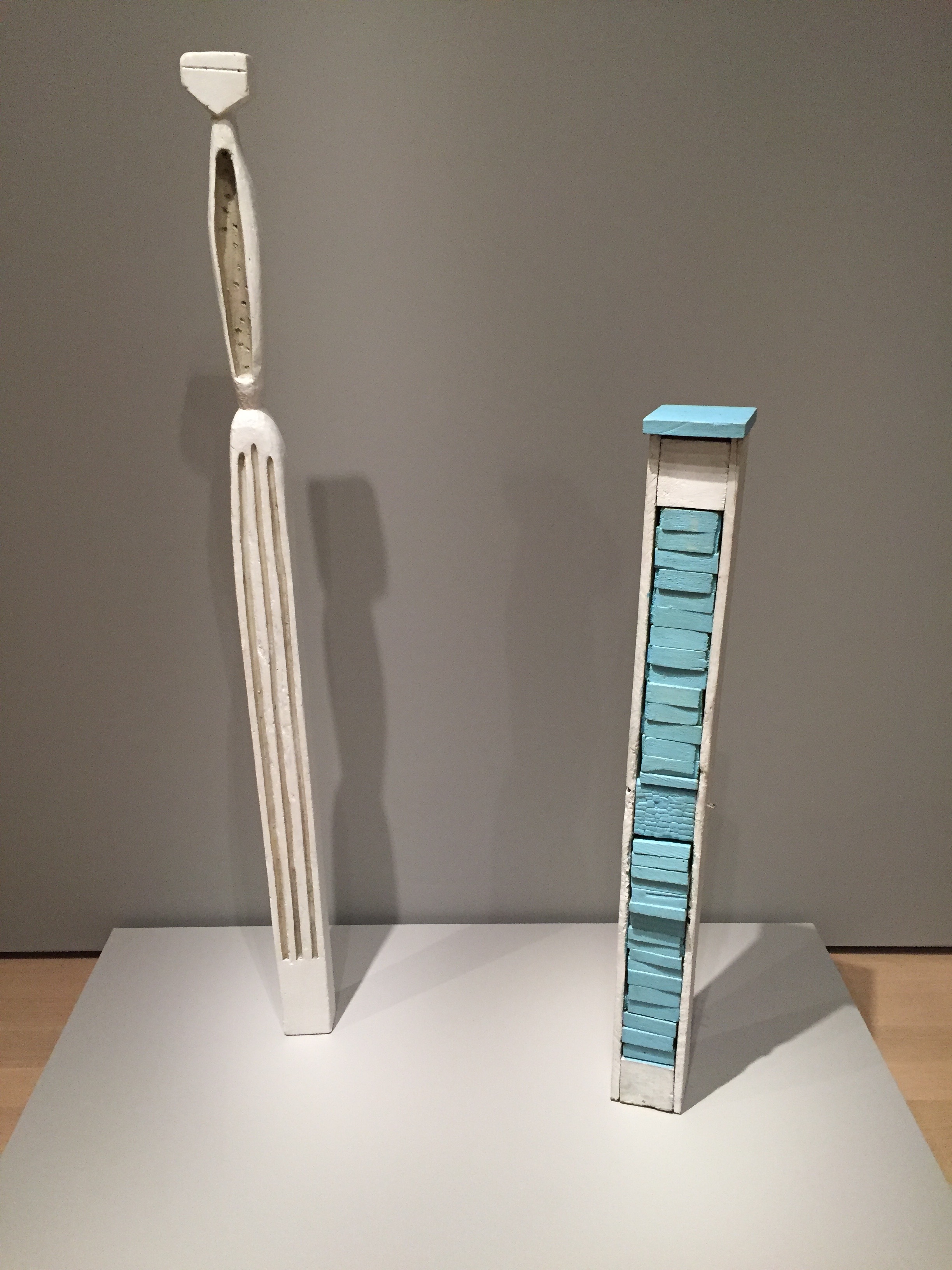

Some things however are very raw and newly poignant: the incorporation of Bourgeois’s intimate diaries, the late textile books which returned her to “women’s work” in an entirely fresh way, her kinship to other artists--Picasso (in the wooden sculptures), Frankenthaler (in the blacks), the role of architecture, then considered men’s work, but appropriated by Bourgeois in a highly original fashion.

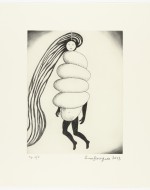

Bourgeois was impelled to claw back dark, unhappy feelings and memories (WW1 and the disappearance of her father and death of her relatives, consequent physical displacement, the death of her mother, a family history of instability, her father’s long term affair with her governess) all of which inhabits the work in original and often lighthearted ways; indeed the juxtaposition of the painful, sentiments of isolation and the free hand with which she tried to dispense with them is truly her work’s greatest power.

Fresh off the Hammer’s Radical Women exhibition (see below) in which pain and anger are displayed with much less opacity, I was surprised at how coming in on little cat feet instead could invoke an equally strong heightened awareness of just how diminished a woman can feel.

According to Wye in the excellent accompanying catalog,

“Bourgeois fought against despair with a fierce will and directed her formidable intelligence to comprehending her emotions. Art was the tool, and making it was empowering. It allowed her, she said, 'to re-experience the fear, to give it a physicality so I am able to hack away at it.' “

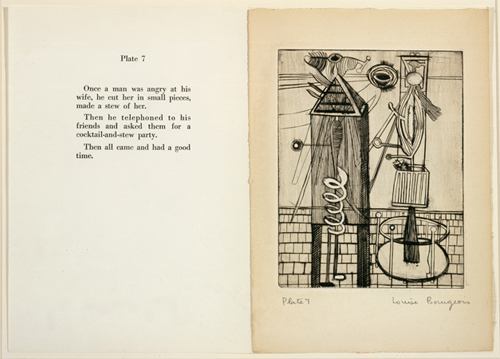

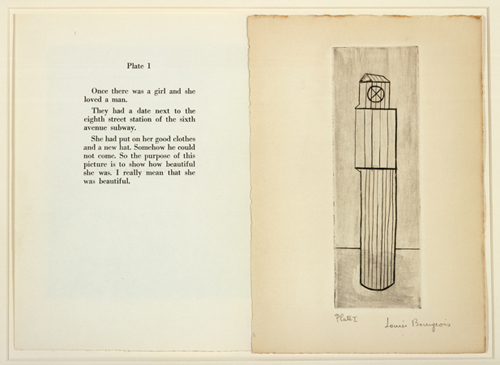

Holding your demons at bay by enlisting your work as the front line against failure resonates with many of us and there is no shortage of Bourgeois idolatry. At the Guggenheim in 2008, there was a Bourgeois retrospective which belatedly woke me to the power and incision of her printed work, writings and parables. Tucked into one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous ramp corners in the museum was her most famous art book, He Disappeared into Complete Silence which tells an Aesop's fable of girls and women who have somehow been forgotten.

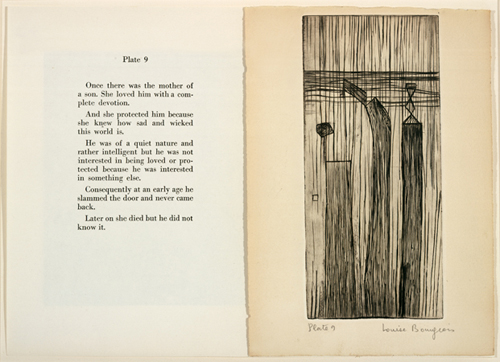

Once there was a girl and she loved a man.

They had a date next to the eighth street station of the sixth avenue subway.

She put on her good clothes and a new hat. Somehow he could not come. So the purpose of this picture is to show how beautiful she was. I really mean that she was beautiful.

Though I did not know it at the time, I was overdue for a rupture of my own: nevertheless there was something about Bourgeois’s expressive and personal architectural imagery in which she both inhabits and melds her body with the tall NYC skyscrapers she so admired which lodged in my brain. I returned to these texts later on with a feeling of solidarity that only great art can invoke.

At MoMA this series is more fully explored and set within the context of the rest of her work. Though Wye says she did not have an actual affair with Alfred Barr, then head of MoMA, clearly, despite her happy marriage (husband Robert Goldwater’s support was crucial to her as she made her way from Paris-New York and anxiety-ridden mother of three to art world giant) she highly valued Barr’s careful attention to her and her work.

Many powerful women have written about overcoming fear—but none so eloquently, with so few words, as Bourgeois. Bourgeois’s writings, both the ones she incorporated into her art and the more private journals that have now come to light show she was an excellent writer and stylist, both poetic and psychologically intuitive and precise.

Another revelation was her work with textiles rather late in her career, going back to a domestic art after the huge spiders and sculpture, easier to manage certainly, as she aged, but also an acknowledgement that she had never abandoned this “feminine” side and its application to her work. No longer needing to impress “the guys”, she was able to set her hand to whatever she liked.

Take a look at Wye’s talk at MoMA for futher intimate details of Bourgeois’s life from her trusted curator and devoted friend. The show is brilliantly installed, a muted gray background the perfect choice to show off the works which speak softly but carry a big stick.